Dispatch #11: Bihar Elections- Curated content and resources

In case you want to know more about the politics and socio-economic issues of Bihar, we got you covered.

1) Absence of a charismatic Dalit leader opens up space in poll-bound Bihar: The unified Dalit vote may be a myth in this election in Bihar. They may move horizontally in the absence of tall leaders towards political parties which can provide them space and representation. In spite of Manjhi’s support to the NDA, a section of Dalit voters may be drawn to the RJD and some may choose the CPI (ML). It is interesting to observe that in spite of various efforts by JD(U) leader Nitish Kumar, in a section of Mahadalit communities and especially among Dalit women, Prime Minister Narendra Modi enjoys much admiration. Policies such as Ujjwala Yojana and Jan Dhan Yojana, in which Rs 500 reached their bank accounts, make them believe that Modi is working to provide them a dignified life and alleviate their terrible hardship. Such existential requirements of dignity may lead them to various political groups. No doubt, Dalit votes will become fragmented but, in this process, they may also try and find new options for their empowerment.

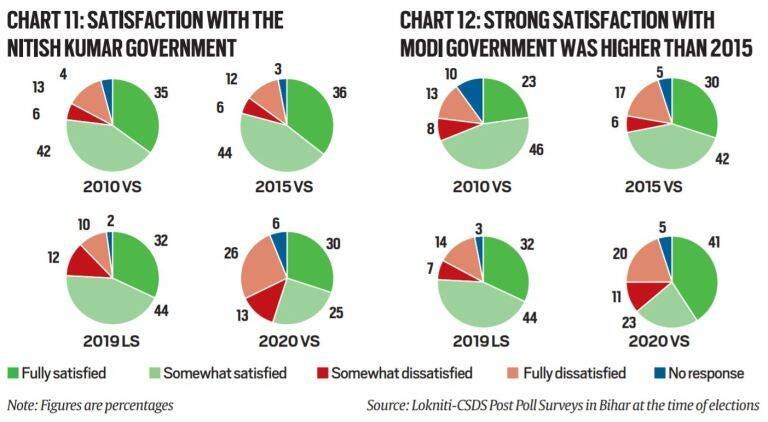

2) ‘Bankable’ Nitish’s poll appeal now under cloud: From the 2000s onward, fiscal decentralisation coupled with welfarist chief ministers created a winning electoral combination for state-level leaders. In certain states, voters attributed newfound welfare benefits to their chief ministers and continued to vote them back to power. But the centralisation around Modi has changed the game. Voters attribute their welfare benefits to the Centre and Narendra Modi, leaving welfarist chief ministers — particularly those aligned with BJP — without their main political appeal. When respondents were asked upon whose work they will base their vote, 16% of voters said the Nitish government while 27% of voters said the Modi government (with 29% saying the MLA). When just looking at NDA’s supporters, 33% said they would base their vote on work done by the Nitish government, with 42% basing their vote on the Modi government (and just 8% on the MLA’s work). In short, in the electorate as a whole — and even among NDA supporters — the main political appeal lies with Narendra Modi even with the scale of welfarist and development expenditure from Nitish Kumar’s government.

3) Dignifying Democracy in Bihar- Lalu Prasad Yadav, Social Justice and Equality: During Lalu Yadav’s regime there were political strategies aimed at ‘lower’ caste empowerment. One, the Janata Dal politicised the rural poor by convening public rallies through which they developed shared solidarities cutting across caste distinctions. Jeffrey Witsoe tells us of awareness rallies organised by the state government during the Yadav years in which peasants and the rural poor would be invited to travel to and demonstrate their collective presence in the heart of Patna, creating moral panic among the city’s gentry. Two, Yadav developed personalised networks with politicians and political mediators, not on the basis of their caste but on their ability to deliver him votes. His cronies included Rajputs and Bhumihars, who styled themselves as ritually superior to Lalu’s Yadav community. The image of superior-caste Rajput and Bhumihar leaders supplicating before Lalu Yadav thrilled the Chief Minister’s rural constituency, symbolising to them an inversion of the conventional idioms of the paternalism to which they had been subjected during the colonial and Congress regimes. Three, Yadav’s government systematically emasculated the state bureaucracy as well as the police dominated by the privileged castes. His Janata Dal government famously reined in the police when landless labourers sought to occupy agricultural properties illegally held by the landlords, imbuing among the rural poor, especially the historically oppressed Dalit and OBC populations, a sense of dignity.

4) Wheels of power- Long-term effects of the Bihar Cycle Programme: A girl who got a cycle under this scheme has a 27.5% higher chance of completing grade 10 than a girl who did not get a cycle. This is the direct intended effect of the scheme. What is surprising, however, is that the girls continue to pursue their studies even when the cycle cannot directly help them. The senior secondary schools and colleges are usually located further away from the villages in Bihar and the density is very low. This implies that the girls cannot use the cycles to access them. Yet, our results show that a girl who went to school after the cycle yojana was introduced is 22.9% more likely to go ahead and complete her school education than a girl who did not get a cycle. Hence, the cycle is not just helping address a barrier to accessing secondary schools; it is also vehicle of change and a means to new aspirations.

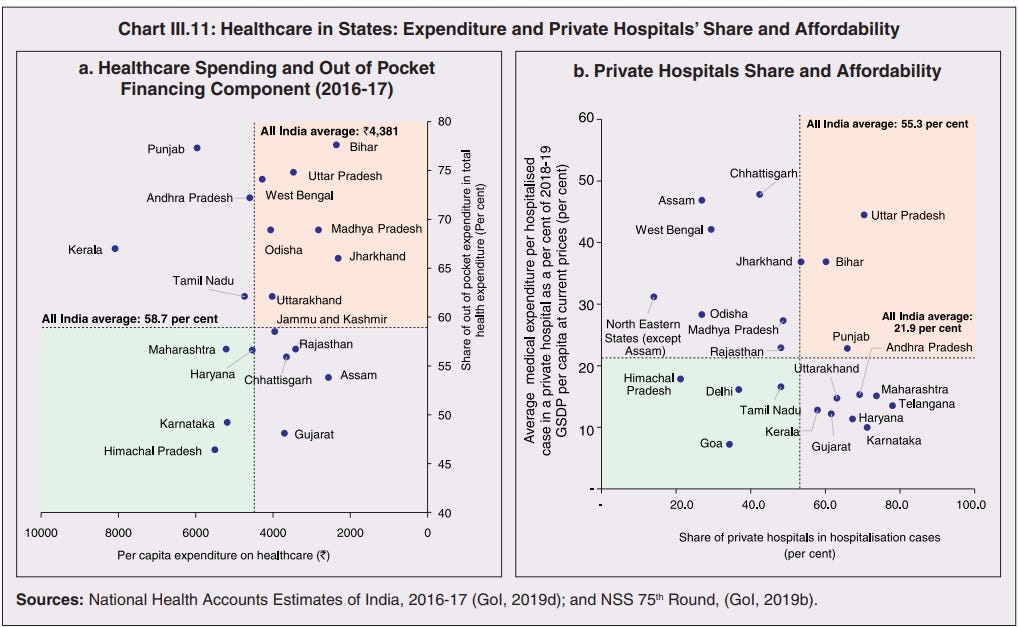

5) RBI’s latest data shows that Bihar has one of the highest out-of-pocket expenditure in health financing: Significant inter-state disparities exist in access to and affordability of healthcare. Himachal Pradesh acquits itself well in providing government healthcare as well as in keeping private healthcare affordable, while Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Jharkhand will need some catching up. Individuals’ spending on healthcare is low in these states, financed largely from out of pocket, with high reliance on private facilities for hospitalisation that is prohibitively expensive and crowds out medical access to the poor. This requires urgent attention from state governments to prepare their states to meet the healthcare challenge from COVID-19 and future pandemics.

6) The BJP grapples for the crucial OBC vote in Bihar: The results of the socio-economic and caste census of 2011, the first attempt to tally the sizes of India’s castes in eighty years, are yet to be released in full. By most educated estimates, however, OBCs constitute around fifty percent of Bihar’s population today, and Muslims, the Scheduled Castes and the upper castes each account for something in the vicinity of fifteen percent each. To have any chance of electoral success in the state, political parties and coalitions must secure a substantial share of the OBC vote, and bolster it with support from some other, non-OBC electorates. Bihar’s OBCs comprise numerous caste groups, the largest of which include the Yadavs, Nishads, Kurmis and Koeris. Yadavs, who are thought to form around 15 percent of the state population, traditionally favour the Rashtriya Janata Dal, led by Lalu Prasad Yadav. Nitish Kumar, Bihar’s current chief minister and the leader of the Janata Dal (United), has a large base among non-Yadav OBCs, including his own Kurmi caste, as does the Rashtriya Loktantrik Samata Party leader Upendra Kushwaha, who has particular appeal among his Koeri caste. The BJP is said to have consolidated support among the Nishads since 2014—thought to form at least ten percent of the population, and so the largest caste group among the state’s Extremely Backward Classes, a sub-category of the OBCs.

7) Bihar’s Women Win Against Alcohol But Lose To Illicit Liquor, Drugs: While the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data show a decline in cases of domestic abuse usually fuelled by alcohol consumption, as we explain later, prohibition has also had unintended consequences: A parallel economy of illicit liquor trade is flourishing in Bihar even as the state is losing out on revenue from alcohol sales. Bootleggers are selling alcohol at a higher price, pushing the poor towards cheap drugs and hooch. A World Health Organization fact sheet links intimate partner violence to alcohol consumption, “especially at harmful and hazardous levels”. It cites a multi-country study in Chile, Egypt, India and the Philippines that “identified regular alcohol consumption by the husband or partner as a risk factor for any lifetime physical intimate partner violence across all four study countries”. In Bihar, cases of domestic violence under Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code (cruelty by the husband or his relatives) fell 37% since the liquor ban, while the crime rate--or cases per 100,000 women--fell 45%. Countrywide, during the same period, cases rose 12% and the crime rate rose 3%.

8) If Women Could Decide, Bihar Wouldn’t Have A Population Crisis: At 3.4, Bihar reports India’s country’s highest fertility rate, but if all the women in the state were to only have the number of children they wanted, this rate would have been 2.5 children per woman, according to the 2015-16 National Family Health Survey (NHFS-4). Unmet need reveals the gap between a woman’s reproductive intentions and her contraceptive behaviour. The gap could be caused by lack of access to contraceptives, but it could also reflect cultural, social and religious beliefs that forbid contraception or do not allow women to take independent decisions about family planning. Women with no education and from the poorest families had the highest total unmet need in Bihar--40.1% and 40.6% respectively, according to a NHFS-4 fact-sheet. Sexually active women between 35 and 39 years of age had the highest unmet need--42.5%. About 12.5% of total births occurred among teenaged women, the third highest number in this category in India.

9) 94% Bihari Women Know Of Contraception, But 1 in 5 Use It: We found that while 94% of sexually active women aged 15-49 knew of at least one of the eight contraceptive methods in use, only one in five (20.1%) were currently using any. More unmarried, sexually active women use contraceptives (42%) than married ones (27%), and education increased women’s awareness of contraception. Given the widespread awareness about contraception in Bihar, why is contraceptive use so low? The biggest reason, our survey suggested, was a fear of side-effects (15%). This was followed by the desire to conceive (11.7%), general disinclination to use contraceptives (8%) and opposition from partners (7.8%). (The other reasons included lack of access, lack of knowledge, and religious objections.) The burden of contraception also lay almost entirely on women.

10) For Bihar’s women, benefits of prohibition wane as alcoholism persists in their villages: A study conducted by the Asian Development Research Institute, or ADRI—a Patna-based think tank that conducts social-science research—found that the liquor ban has had a significant impact on the household economy. The study, led by the economic researcher PP Ghosh, found a substantial increase in the purchase of milk products and various other items such as expensive saris, processed food, furniture, and vehicles, in the first six months after prohibition, compared to the previous year. According to the study, the purchase of honey and cheese increased by 380 percent and 200 percent, respectively, within six months after prohibition was enforced in April 2016. “The men are scared to drink openly or to hit their wives,” Lakshmi Devi, a 50-year-old resident of a Kamla Nehru Nagar, a slum near Adalatgunj, told me.

11) State Incapacity by Design: Understanding the Bihar Story: The Indian state of Bihar has long been a byword for bad governance. It was however governed particularly badly between 1990 and 2005, and has since experienced something of a ‘governance miracle’. How can we account for the 1990–2005 deterioration? The answer lies in the interaction of three factors. The first was the type of leadership exercised by Lalu Prasad Yadav, who was Chief Minister throughout most of this period – even when his wife formally occupied the post. The second lies in electoral politics: the need to maintain the enthusiasm and morale of an electoral coalition that Yadav had constructed from a number of poorer and historically oppressed groups. Such was the scale of poverty among this core electoral coalition that Yadav had limited prospects of maintaining its cohesion and allegiance through the normal processes of promising ‘development’ and using networks of political patronage to distribute material resources to supporters. More important, that strategy would have involved a high level of dependence on the government apparatus, that was dominated by people from a number of historically-dominant upper castes. That is our third factor. Yadav preferred to mobilise his supporters on the basis of continual confrontation with this historically oppressive elite. He kept public sector jobs vacant rather than appoint qualified people – who were mainly from the upper cases. He tried to micro-manage the state apparatus from the Chief Minister’s office. He denuded the public service of staff. He was then unable to use it to deliver ‘development’. We show that, among other things, the Bihar state government sacrificed large potential fiscal transfers from the Government of India designed for anti-poverty programmes because it was unable to complete the relevant bureaucratic procedures. Yadav knowingly undermined the capacity of the state apparatus. There are parallels in many other parts of the world. Low state capacity is often a political choice.

In a brilliant thread, Harvard’s M R Sharan has described how in Bihar, a grievance redressal scheme encapsulates three broad development themes- development projects, decentralization and responsive government.

12) Something to Complain About- How to make government work for minorities? Since politicians’ incentives to collaborate matter for public good provision, designing institutional mechanisms to fix them could improve outcomes. This paper is the first to show that a formal complaints technology can be effectively used not merely to address complaints by citizens -- as is common across the world -- but by members of the local state themselves. Policymakers could incorporate this in the design of such technologies, particularly in diverse and more decentralized set-ups (Bardhan and Mookherjee 2006). Unlike political reservation (Duflo and Chattopadhyay 2004), an advantage is that formal complaints systems can be accessed by the entire population.

13) Cycling to School- Increasing Secondary School Enrollment for Girls in India: In this paper, we evaluate the impact of an innovative program in the Indian state of Bihar (launched in 2006) that aimed to improve secondary school access for girls without additional school construction. The program provided all girls who enrolled in grade 9 with funds to buy a bicycle to make it easier to access schools. The “Cycle program” was therefore a “conditional kind transfer” (CKT) and had features of both demand and supply-side interventions. The enrollment conditionality is analogous to demand-side CCT programs, but the bicycle also improves school access by reducing the time, distance, and safety cost of attending school, which are features of supply-side interventions. The program has proven to be politically popular and has been replicated in other states across India, but there has been no credible estimation of its impact. Our main result is that being in a cohort exposed to the Cycle program increased the probability of a girl aged 14 or 15 being enrolled in or having completed grade 9 by 32 percent (a 5.2 percentage point increase on a base age-appropriate enrollment rate of 16.3 percent). Further, the program also bridged the pre-existing gender gap in age-appropriate secondary school enrollment between boys and girls (of 13 percentage points) by 40 percent.

14) In Bihar, the subdued narrative of the silent voter: In hindsight, the social base of the electoral narratives resonating across Bihar had three distinct takers. One, while there was a general sense of disappointment with Nitish Kumar, not every section wanted to desert him. While a significant section of upper castes deserted him, the lower backward castes and Mahadalits did not seem to have shared the enthusiasm of a ‘pro-change’ narrative. Rather, they remained silent on the question of leadership. Two, while a majority of upper castes turning their backs on Nitish Kumar ensured the JD(U)’s defeat in as many as 30 seats by voting for rebel candidates from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) fielded by regional parties such as Lok Janshakti Party (LJP) and the Rashtriya Lok Samta Party (RLSP), they were wary of the prospect of Tejashwi Yadav (of the Rashtriya Janata Dal, or the RJD) becoming the alternative. This is despite the fact that he attempted to consciously shift the prevailing perception of the RJD, from being a particular caste-centric to an umbrella party.

15) Bihar Assembly Election 2020- How to read the Bihar results? A phase-wise analysis of the elections suggests that the NDA gained a massive momentum after the first phase. While the MGB won 67.6% of the 71 ACs in the first phase, its strike rate dropped to 44.7% and 26.9% in the second and third phase. For the NDA, strike rates improved in each phase; from 29.6% in the first phase to 54.3% and 66.7% in the second and third phase. This pattern suggests a silent counter-polarisation behind the NDA, indication that its strategy of attacking the MGB by evoking memories of “jungle-raj”; a term often used to attack poor governance when the RJD was in power from 1999 to 2005, has paid rich dividends. The fact that the MGB was shown as gathering momentum as the polls progressed might actually have aided this counter-consolidation. An HT analysis of gender-wise voting pattern shows that women vote might have played a big role in the NDA’s victory.

16) Bihar Assembly Election 2020- NDA’s seat share rose with every phase: The fact that the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) has managed to secure a majority in the Bihar elections is largely an outcome of its ability to gain momentum after the first phase of polling in the state. The irony involved here is difficult to miss, as it was the NDA which entered the contest as the favoured coalition against the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD)-led Mahagathbandhan (MGB). An HT analysis of phase-wise statistics shows this clearly. On every indicator, be it strike rate, vote share, or victory margin, the NDA performance improved discernibly from the first to the final phase of the elections. Phase-wise statistics also suggest a growing counter-polarisation against the RJD, which could have been the result of the NDA evoking the memories of RJD president Lalu Prasad from 1990 to 2005.

17) Bihar Assembly Election 2020- How women steered NDA towards majority? There is a massive lead of 19 percentage points in the NDA’s strike rate (seats won as a proportion of those contested) in ACs where actual women voters outnumbered actual men voters. In fact, the higher the share of women voters in a constituency, the better is the NDA’s performance. This is evident in a quintile (bottom 20% to top 20%) distribution of all ACs by the share of actual women voters. The advantage or lack of it among women voters is consistent for parties in either the NDA or the MGB, which suggests that they voted for government formation rather than local factors. Nitish Kumar’s government in Bihar has tried to consolidate women voters by schemes such as distribution of bicycles for girl students and announcing prohibition in 2016.

18) BJP’s Bihar performance sets template for its expansion in states: Elections in the state and the party’s performance should convince analysts who continue to be sceptical about the future dominance of the BJP. Modi was successful not only in getting his party re-elected but in improving its performance. Now, two dimensions of dominance constitute the next stages in the project. One is, as mentioned above, expanding its footprint in the remaining states. In Bihar, the BJP has come close to that. The other is to make sure that the larger Hindutva narrative becomes the central idiom. That implies changing the ground rules of political rhetoric and imagination. The existence of parties like the RJD, SP, BSP, DMK and so on is important because they have their own rhetoric to fall back on and that is why Bihar matters — just as Tamil Nadu next year or UP later will.

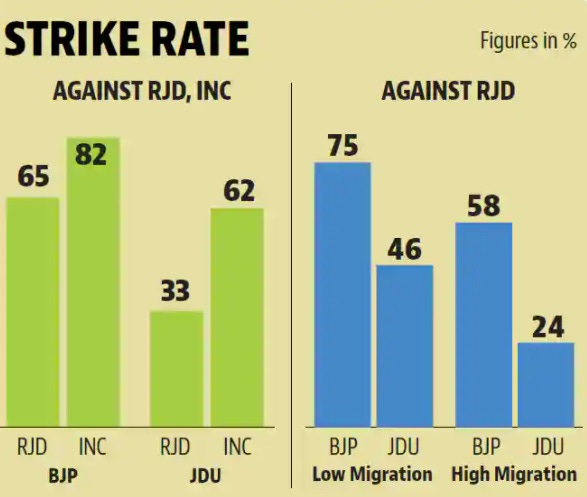

19) Bihar Assembly Election 2020- With superior poll strike rate, BJP may call the shots in NDA: The vote share differences manifested in radically different strike rates (percentage of contested seats won) — with the BJP scoring a strike rate of 65% and the JD(U) of just 37%. Nowhere was this difference more evident than in head-to-head contests with rival RJD. In the 57 head-to-head contests against the RJD the BJP had a strike rate of 65%, while the JD(U) had a significantly weaker 33% in its 61 head-to-head contests against the RJD. Against the RJD, the JD(U) dropped from a 46% strike rate in low migration constituencies to a strike rate of just 24% in high migration constituencies. Even with RJD’s increase in vote share, the BJP’s strike rate remained impressive across low (71%) and high (58%) constituencies.

20) Bihar elections- Modi’s Covid-19 lockdown battered Indians – so why are they still voting BJP? A better way to explain Tuesday’s results might be in what political scientist Neelanjan Sircar calls the “politics of vishwas” – trust or belief in a strong, charismatic leader. Sircar argues that standard models of democratic accountability would be hard pressed to explain BJP’s sweeping 2019 Lok Sabha win, despite a slowing economy and disasters such as demonetisation. Instead, a better explanation for the BJP’s winning streak is the trust Indian voters respose in Modi – built up by Hindu nationalism as well as the party’s control of the media and its strong organisational machinery. Sircar’s thesis fits even better with Tuesday’s results. In more standard models of democratic accountability, the BJP should have suffered electorally for the harsh, unplanned lockdown it imposed on India. Instead, poor Indians seem to have magnanimously ignored their own distress and voted driven simply by their “vishwas”, belief in Modi.

21) Decoding the close Bihar verdict: As the counting of votes in Bihar continued through the day on Tuesday, the close nature of the battle became increasingly obvious. The fact that the NDA managed a narrow victory became the clear headline. Yet, the verdict of the Bihar voter has multiple small stories that add up to the big picture. In this article, we hope to unpack these multiple strands. Nitish Kumar was able to overcome the inevitable fatigue of being in power for a decade. This was partly on account of the Mahagatbandhan (MGB) not being seen as a viable option, and partly due to the positive sentiment associated with the performance of the central government. The caste calculus continued to offer important insights while the youth vote got divided on gender lines.

22) How Nitish Kumar won Bihar, again? The dyad of an alternate social coalition and the across-groups constituency of governance nurtured by Nitish’s Janata Dal United, along with its ally, the Bharatiya Janata Party, over last two decades in Bihar continues to be a potent force against the rival social alliance led by the Rashtriya Janata Dal. Despite some fissures, Nitish’s social alliance – of OBCs, especially Economically Backward Classes, Mahadalits, Pasmanda Muslims – and its rejection of anti-upper caste rhetoric held against the grand alliance’s coalition – Muslims, Yadavs, a few groups within the EBCs, and a few sub-castes within the Dalit community. More significantly, the force of anti-incumbency was tamed because Nitish’s impressive record of governance in his first two terms wasn’t made the yardstick to measure his last five years in office. Instead, it was measured against anxieties about what the RJD-led alliance could damage. Nitish’s third term was seen as being lacklustre only when measured against his first two terms, but it was still preferable to apprehensions of misgovernance that the grand alliance evoked in civic memory.

23) What does caste profile of MLAs in Bihar tell us about politics? The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Congress are primarily upper caste parties when it comes to distributing ticket. Our data shows that 47.3% of the BJP’s candidates were upper castes, predominantly Rajputs. Banias, who are considered as Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in Bihar, also find substantial representation compared to their demographic weight. The rest of the tickets distributed to OBC candidates are split in half between Yadav and non-Yadav OBCs. The fact that the BJP does not give tickets to Muslims, allows it to maintain the social balance among Hindus. The Congress distributed 40% of its 70 tickets to upper-caste candidates and 17% to Muslim candidates, again across sub-regions. The JD(U) continued to favour Kurmis among OBCs but gave equal representation to Yadav candidates. The remaining 25% of tickets given to non-Yadav and non-Kurmi candidates were divided between at least twelve other groups, each receiving a handful. The RJD remained true to its base by distributing nearly a third of its tickets to Yadav candidates. The remaining 70% was distributed among a large array of castes, chosen according to local demography and local patterns of dominance. 12.5% of its tickets were given to Muslim candidates, across most sub-regions.

24) RJD didn’t buy Facebook, Google ads. It cost them Bihar: By not advertising on Facebook, the RJD allowed its opponents to set the agenda and perception of the party. For example, there were several pages that attacked the RJD and its leader Lalu Prasad Yadav and hosted a number of uncivil ads. The most prominent parody account was ‘Rashtriya Jangal Dal’. A reader, not careful enough, would mistake it for the original account of the RJD. Another account attacking the RJD was ‘Bhak Budbak’. These two accounts together spent close to Rs 15 lakh on Facebook advertising beginning the first week of September till 7 November. Several of the ads issued by these two pages were subsequently taken down by Facebook for violating its ads policy. Yet, the manner in which these pages were able to exploit the loopholes in Facebook’s political advertising policies in India proves that the company treats the developed and developing markets differently.

25) Decoding the Bihar results in 32 charts- Turnouts, vote shares, victory margins and more: Close elections easily create conflicting narratives and explanations, as most actors concerned tend to read the result in any way that suits them. In this article, we look at the data that this election generated to provide a fact-based explanation of the outcome and provide an explanation on the data’s possible significance. The data is based on Election Commission of India data, scraped on the day of the results and added to the historical data compiled by the Trivedi Centre for Political Data (TCPD-IED: TCPD Indian Electoral Dataset). The team of researchers at Trivedi Centre for Political Data has added a number of variables that enable a detailed analysis of party performance, which we offer here.