Dispatch #10: Bihar mein ka ba?

In this dispatch we will revisit demographer Ashish Bose's demographic indicators to see how is Bihar doing on those fronts. We will also see why India is now counted as an illiberal democracy.

Bihar Elections 2020:

In the next 24 hours Bihar will go into polls. The first phase of polling is on 28th October, the second phase in on 3rd November and the last phase is on 7th November. While the exit polls are saying that the NDA will come back with Nitish Kumar as the CM, it’s only on 10th November that we will know who is the choice of the people of Bihar. Bihar has always been considered a basket case, hence issues of development, employment and migration are topping the charts in all the election rallies.

The high decibel election campaign can not only be seen in the rallies around Bihar but also in the virtual world. A series of YouTube videos have emerged in the past few weeks that are questioning the incumbent government’s 15 years of achievements. While the Congress came out with ‘Ka kiye ho?’ video, YouTuber Neha Rathore is asking ‘Bihar mein ka ba?’. In a befitting reply, another YouTuber Mithila Thakur in her video is talking about the development Bihar has seen in the past few years.

This question has puzzled political scientists, economists, sociologists and demographers for a very long time. In 1980s, demographer Ashish Bose coined the term BIMARU states while commenting on how Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh have poor demographic indicators that is resulting in these states lagging from the rest of India.

In a 2015 EPW paper, economist Vinita Sharma revisited Bose’s indicators once again and argued that the BIMARU states have not been able to converge with the rest of India and the regional disparities remain despite of high economic growth.

Our analysis shows that the BIMARU states have not converged to the national average. For all the demographic indicators considered, the BIMARU states as a whole continue to remain backward relative to the national average. However, this is not to say that these states have made no progress. All of them have individually improved along most of the demographic indicators, and, as a whole, they appear to be converging to the all India level in five out of the 13 indicators considered. The pace of this convergence has been slow. For the mean age at marriage and IMR, the percentage gap remains nearly the same. In the remaining indicators, the BIMARU states have diverged from the all-India level with an increasing percentage gap over the years. Thus, speculations based on limited analyses claiming that BIMARU is no longer a valid metaphor for backwardness are simply not true.

-Vinita Sharma, ‘Are BIMARU states still Bimaru?’, EPW

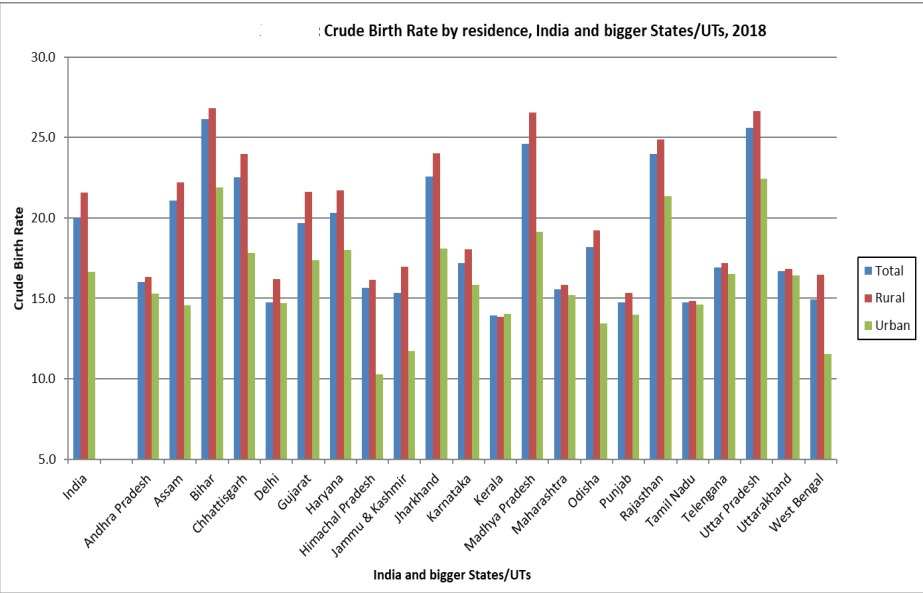

According to the latest SRS report the Crude Birth Rate (CBR), that also happens to be one of the demographic indicators that Bose used in 1980s, is 26.2 which is higher that the national average of 20 and higher than UP (25.6), Rajasthan (24) and MP (24.6).

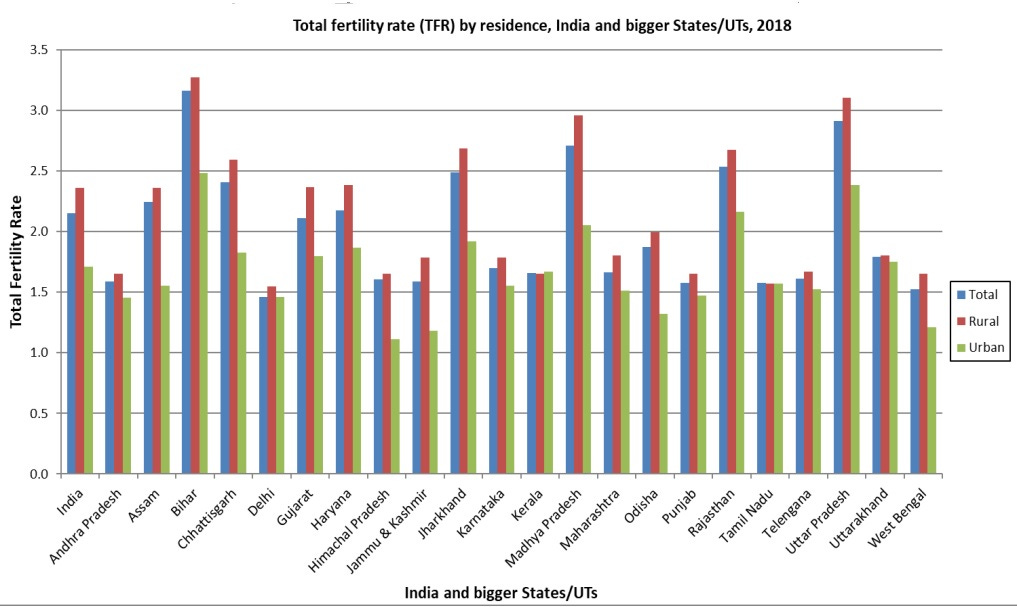

Another critical demographic indicator is the Total Fertility Rate (TFR) which indicates the average number of children expected to be born per woman during her entire span of reproductive period. Bihar has the highest TFR (3.2) which is way higher than the national average of 2.2. After Bihar, it is UP that has the second highest TFR (2.9), followed by MP (2.7) and Rajasthan (2.5).

In a remarkable 2012 paper, titled ‘Bihar: What went wrong? And what changed?’, Arnab and Anjan Mukherji argue that the zamindari system instead of the ryotwari system that disincentivised investments in agriculture ; freight equalization policy that destroyed resource rich Bihar’s comparative advantage for industries to set their shops here and poor governance of Bihar under RJD in 1990s and early 2000s led to the state lagging from other states.

In the latest article, CMIE has unpacked the unemployment conundrum in Bihar. The unemployment rate in Bihar was around 46% in April-May when the lockdown started. It has come down to 12% which is still higher than the national average of 6.7%. The article argues that Tejaswi Yadav’s promise of providing 1 million government jobs if voted to power could be a game changer.

In a brilliant article, scholar Saumya Tewari analysed the gender based budgeting in Bihar, a practice that the state started in 2008-09. Her study claims that the gender budget allocated to women related schemes has increased over the year, yet the institutional capacity is the biggest challenge in Bihar to implement gender budgeting.

The biggest challenge in the implementation of gender budgeting in Bihar is the lack of institutional capacity. Even after 12 years of GRB, Bihar does not have a department (or a minister) or directorate dedicated to women. The Social Welfare Department acts as the nodal department to coordinate and monitor the implementation of United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5- Achieve gender equality and empower all girls and women. A Gender Resource Centre (GRC), set up by the Women Development Corporation (WDC), an autonomous institution responsible for welfare of women and children is the only institution that works towards mainstreaming gender policies and budgeting. The Bihar Institute of Public Administration and Rural Development, which is responsible for training of the administrators in the state, has not conducted any training for institutional building towards GRB observed the study. States like Rajasthan, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh have set up interdepartmental committees to monitor GRB. Bihar has not established such a committee until March 2020.

-Saumya Tewari, ‘Why Bihar Government’s Gender Budget Falls Short In Bridging Gender Gaps’, Behanbox

The history of the political mobilization of the backward castes in Bihar is an interesting one. This history takes you through the decline of the Congress, formation of Triveni Sangh, formation of Samyukta Socialist Party (SSP), emergence of Karpoori Thakur and other Lohiaite leaders like Laloo Yadav, Nitish Kumar and Ram Vilas Paswan. You add another layer of abolition of the zamindari system in Bihar and the emergence of the landed upper backward castes and the story becomes more interesting and complex. Anand Vardhan, in his brilliant article, has beautifully captured this story.

Sanjay Kumar, from the CSDS, in this insightful article has described why the politics in Bihar is different from its neighboring state, Uttar Pradesh. While UP has seen single party domination in the past few decades (BJP in 2017, SP in 2012, BSP in 2007), in Bihar no one party has dominated the landscape and they ahve to depend upon coalition with other caste based parties to reach the magic figure of 122 seats in the state assembly.

On the other side of the political fence, neither the JD(U) nor the BJP have ever been able to win a majority on their own in Bihar, even when contesting on their own. The two parties have been able to form governments only in alliance with each other, or in the case of JD(U), with parties such as RJD. Other smaller parties such as LJP, HAM, Upendra Kushwaha’s Rashtriya Lok Samata Party (RLSP), Mukesh Sahani’s Vikasheel Inaaf Party (VIP) have much smaller support bases, and cannot be expected to form a government of their own. Coalitions are therefore compulsions in Bihar’s politics. The mobilization of caste-based support groups, and the inability of any party to make significant inroads into other party’s support bases has necessitated coalitions in the state in the post-Mandal era.

-Sanjay Kumar,'What separates Bihar’s politics from UP’s?’, Mint

In a brilliant profile of the independent candidate Mukesh Sahni of Vikassheel Insaan Party (VIP), Sarthak Bagchi from the Ahmedabad University has explained the rise of VIP as a political party that represents the demands of Nishad community which is a riverine caste with occupations dependent on rivers and other water resources.

In the post-Mandal period in Bihar, upper backward castes like the Yadavs, Kurmi-Koeri, and Baniyas could effectively capture state power through increased representation. However a large section of the backward castes, represented by the EBCs was not able to do that. As Manish Jha rightly points out, “the marginality and humiliation experienced by a vast section of EBCs (derogatorily called panchapania) never got due attention because of neglect by mainstream political parties and their 'inability to claim identity politics’.” (Jha 2014, 125)

The rise of a demand for better political representation for the Nishad community, along with demands for reservation in jobs and education has to be seen in the context of this long pending “inability to claim identity politics’’. In fact, the metamorphosis of the Nishad Vikas Sangh into a political party for Nishads, the Vikassheel Insaan Party or VIP, also has to be seen in the context of a desire to see increased participation by the community in everyday politics and to have greater bargaining power for the community when negotiating with the state.

-Sarthak Bagchi, ‘Understanding Small Caste-Based Political Parties in India’, The India Forum

Further reading on Bihar elections:

1) In Bihar, the importance of being Nitish Kumar- Since the 1950s, Bihar witnessed two diametrically opposed strands of backward caste assertion, the feudal and the egalitarian. Feudal backwardism revealed the psychology of the dominant backward castes such as Yadavs, the majority of whom aspired to dislodge the deeply-entrenched but numerically-weaker upper castes and emerge as the new political elite. Their political agency was radical and transformative as long as the upper castes were the reference. The moment the reference changed to the lower backward castes and Dalits, they revealed a conservative face. The vanguard of this strand was BP Mandal, a big Yadav landlord.

On the other hand, there was an egalitarian quest of backward caste assertion within the Lohiaite framework. Their aim was not merely to replace the hold of the upper castes by subalterns, but rather to erase the very feudal outlook that social groups in power tend to acquire. This thread was led by Karpoori Thakur, a committed socialist who rose from an extremely humble background. He belonged to numerically insignificant Nai (barber) caste.

This intra-backward representational discrepancy, coupled with the arrogance displayed by dominant Yadavs in the public sphere where the EBCs and Dalits found themselves to be at the receiving end, remains the most abiding memory among the weaker subalterns who support Nitish Kumar.

2) Battle for Bihar: Why it matters?- Nitish has been CM for 15 years now, a longevity sustained by his image of ‘Vikas Purush’, as opposed to Lalu’s ‘Goonda Raj’. However, the memory of his pole vaults since 2014 — sullen resignation as CM after the JD(U)’s Lok Sabha rout in 2014, switch to Lalu to form an unlikely Mahagathbandhan, and an even more unlikely turnaround to embrace the BJP in 2017 and stay in power —lingers. While astute, the metamorphoses might have been one too many in this deeply political state. Nitish is also up against mounting anti-incumbency, with his government seen as stumbling on jobs, coronavirus and floods. Could Nitish’s slogan of his 15 years against 15 years of Lalu be potent enough?

3) Musahar Village’s Lost Hope in Bill Gates Promises of Development- Krishna, Minta, Avdesh, Mamta and Ravinder’s story reflects the lives of over three million Musahars living in hamlets spread across drought-prone Central and South Bihar and flood-prone North Bihar. Their socio-economic status has not changed much in recent years. In Bihar, 96.3% of Musahars are landless and 92.5% work as farm labourers. The figures have not changed much since the 1980s. Literacy in the community is 9.8%, the lowest among dalits in the country. Hardly 1% of Musahar women are literate. The plight of Musahars can be imagined from the fact that they are still not allowed to live anywhere in Bihar except in hamlets earmarked exclusively for them.

4) Why is everyone promising jobs in Bihar elections?- Lack of quality jobs in the state has forced Bihari workers to out-migrate for employment. According to data from the 2011 census, Bihar had the highest share of migrants who moved out for work, employment or business reasons. A 2018 World Bank paper by Gaurav Nayyar and Kyoung Yang Kim found that migrant remittances had a share of 35% in Bihar’s gross state domestic product (GSDP) and positively affected consumption at the household level. A disproportionate dependence on remittance incomes must have hurt Bihar more than other states after the nationwide lockdown imposed in March this year, in the aftermath of the coronavirus disease outbreak. It is natural that discontent with a poor job scenario in the state has become a big issue in the polls which are taking place just a few months after the lockdown.

5) Sustained efforts required to reduce multidimensional poverty amidst the pandemic- The top five states/ UTs in terms of proportion of people affected by non-monetary poverty in 2015-16 are Bihar (52.5 percent), Jharkhand (46.5 percent), Madhya Pradesh (41.1 percent), Uttar Pradesh (40.8 percent) and Chhattisgarh (36.8 percent). The bottom five states/ UTs in terms of proportion of people affected by non-monetary poverty are Kerala (1.1 percent), Delhi (4.3 percent), Sikkim (4.9 percent), Goa (5.5 percent) and Punjab (6.1 percent).

6) Dalit voters will be the X factor in Bihar election — they vote differently than in UP- In socio-economic profile as well as cultural influences, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar are close cousins. There isn’t a yawning difference between the Dalit populations of the two states: 21 per cent in Uttar Pradesh and 16 per cent in Bihar. The indicators of socio-economic depredation of Dalits are also much the same. This is particularly true of eastern UP and Bihar, both characterised by semi-feudal land relations and persistent underdevelopment. Yet, while the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) was a strong force in eastern UP, it is virtually absent in Bihar. In a broad sense, the Dalit energy in UP was cultivated by the BSP in the politics of Ambedkarism and the idiom of everyday assertion, whereas in Bihar, it grew in the politics of Marxism and the idiom of class war. As Marxism atrophied under its own contradictions, the political consciousness of Dalits got subsumed within the mainstream politics of Bihar.

7) ‘Let The Men Say What They Have To, I Do What I Have To’- Bihar’s gender indicators show that it lags behind national averages--its female literacy rate has gone up from 37% to 50% between 2005-06 and 2015-16 but this is still below the national average of 68.4%, according to the National Family Health Survey 2015-16. It has the worst female labour force participation rates among all states--4.1%, against the national average of 23.3%, according to the National Sample Survey 2017.

8) How Nitish Kumar built new social coalitions during his 15 years in power?- After twice coming close to the seat of power — in 2000 and the dissolved assembly of February 2005 — the Nitish-led NDA finally clinched power at Patna in November 2005. The broad social coalition he had crafted over the years, and his increasing popularity as a symbol of change in governance, had carried the day for him, though he was aware that the RJD-led combine was still a numerically formidable force and was waiting to make a political comeback. While Nitish focused on the wide range of challenges confronting the state, from governance to law and order, he kept an eye on social engineering to sustain his Lohiaite project as well as a longer innings in power.

9) In Bihar, contradictions of aspiration, representation: That Bihar went from bad to worse during the decade and a half long regime of Lalu Prasad Yadav is an objective fact. This is borne out by a comparison of Bihar’s per capita income with all-India figures. The ratio of Bihar’s per capita Gross State Domestic Product and India’s per capita GDP fell from around 0.4 to 0.3 during the period when Lalu Yadav or his wife Rabri Debi held power in the state. This trend reversed almost immediately after the JD(U)-BJP alliance got power in 2005. While this ratio has been improving continuously, Bihar continues to be among the worst performing states in terms of per capita GSDP.

In India, democracy is in decline:

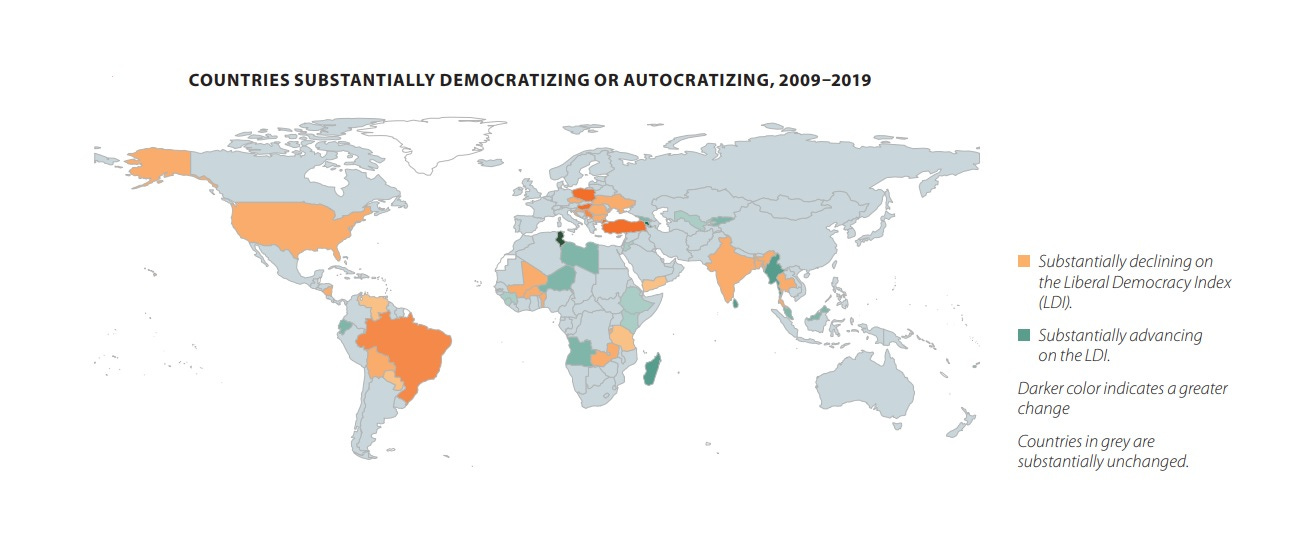

According to the Democracy Report 2020, published by the V-Dem Institute, situated in University of Gothenberg in Sweden, India’s Liberal Democracy Index (LDI) has declined and the country is heading to become an autocracy. LDI is the measure of elections, freedom of expression and media, freedom of association and civil society and the rule of law. The report claims that between 2009 and 2019 there is a substantial decline in the LDI in India.

The median governing party in democracies has become more illiberal in recent decades. This means that more parties show lower commitment to political pluralism, demonization of political opponents, disrespect for fundamental minority rights and encouragement of political violence.

-V-Dem briefing paper

Good Reads:

1) When democracy fails the poor- In many settings, the economic elite can exploit their social connections and economic power to buy out poor voters. This, along with lower literacy and less access to relevant political information, can further weaken the ability of the poor to use their vote to hold politicians accountable, Pande writes. She suggests that reforms in democratic institutions should ensure effective enfranchisement of the poor, transparency initiatives, and mechanisms to enable greater citizen engagement with state officials. This can improve the ability of democracies to deliver policies that can change the lives of the poor.

2) Has Mandir edged out Mandal agenda? How did the BJP gain support among the votaries of Mandal? Mandal worked by creating fissures in a monolithic Hindu vote bank. The BJP has undermined Mandal by creating further fissures in this vote bank. One place where this strategy has been the most successful is Uttar Pradesh. A look at sub-caste wise vote shares for the 2019 Lok Sabha elections from the National Election Study conducted by the Centre for Studies of Developing Societies, Lokniti makes this clear. The only sub-castes where the grand alliance of Samajwadi Party (SP) and Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) had an edge vis-a-vis the BJP were Yadavs and Jatavs. These two sub-castes are the primary support base of the SP and the BSP, but put together they only have around 20% share in the state’s population. The BJP had a huge advantage among all other Hindus, including OBCs and SCs. The coming together of the SP and BSP was described as a grand coalition of Mandal. In the end, it was just a coalition of two sub-castes and Muslims.