Dispatch #110: Why better policies need smarter states?

This dispatch argues that the state capacity must be understood in terms of its alignment with specific policy design tasks such as analytical, operational, and political.

A few years ago, during a policy consultation with a state government, we were discussing an ambitious reform proposal. As the conversation gained momentum, a senior policy researcher remarked, almost dismissively, that the state should abandon initiatives for which it lacks the necessary capacity.

The statement wasn’t surprising. Many of us had heard similar sentiments before, and there are numerous examples in the Indian policy-making and implementation ecosystem that seem to justify such a proclamation. But it stuck with me. What exactly did he mean by “state capacity”? Capacity to plan? To implement? To coordinate? To persuade? To manage the expectations of the stakeholders?

That moment set me off on a journey to understand the idea of state capacity more rigorously. I began reading everything I could, from historical institutionalist theories to contemporary studies in public administration. I discovered that while the term was everywhere in governance literature, it was rarely defined with precision. More importantly, most discussions treated capacity as a static trait, something a state either had or lacked, rather than as something dynamic, distributed, and context-dependent.

That’s why I found Azad Singh Bali and M. Ramesh’s paper Policy Capacity: A Policy Design Perspective so compelling. It doesn’t just dissect the idea of capacity, it reframes it. Rather than asking whether a state is strong or weak, the paper asks a sharper question: what kind of capacity is needed to design and deliver effective policy, and where should it reside?

In this post, I walk through the key ideas in the paper and reflect on how this framework offers a more practical, design-oriented approach to understanding what governments need to solve problems.

From State Capacity to Policy Capacity: Reframing the Debate

Let’s begin with the conceptual shift this paper makes.

Scholars have defined state capacity in many different ways, depending on what aspect of governance they focus on. For instance, Rothstein (2011) argues that a capable state upholds the rule of law and treats citizens impartially. Fairness, in his view, is central to capacity. On the other hand, Weiss (1998) and Hobson (1997) emphasize the importance of a strong, autonomous bureaucracy that can plan effectively and act independently of narrow political pressures. Other definitions focus more on legitimacy and coordination. Painter and Pierre (2005), for example, describe state capacity as the ability of governments to make “intelligent collective choices”, that is, decisions that are coherent and supported across different parts of the system.

Each of these perspectives sheds light on an important piece of the puzzle. But as Bali and Ramesh point out, these definitions often treat capacity as a single, overall trait as if a government either has it or doesn’t.

What they propose instead is to shift the focus from broad institutional traits to the specific work of policy design. Rather than ask “Is this a capable state?”, they ask: Can this government design and deliver good policy?

This is what they call policy capacity - the ability of a government (at various levels) to make informed, context-sensitive, and problem-oriented decisions about how policies are crafted and implemented.

This more focused lens helps in two important ways:

It moves the conversation from abstract discussions about “strong states” to the concrete and practical challenge of solving real-world problems.

It allows us to break down capacity into smaller, more manageable parts like the ability to analyze problems, coordinate between actors, manage budgets, or build political support and to locate these capacities at the level of individuals, departments, or systems.

In short, while traditional views of state capacity highlight important features like rules, institutions, or legitimacy, Bali and Ramesh make the case that we should pay closer attention to how governments design policy because that’s where capacity is most visible, and most essential.

Capacity for What? Start with the Problem

Too often, capacity-building efforts begin with a shopping list: train more staff, install better IT systems, write more manuals, create new departments. But these efforts are rarely anchored in the specific problems a policy is meant to solve.

That’s why this paper insists on flipping the question: instead of asking “what capacity do we need?”, ask “what problem are we trying to solve and what kind of capacity does that require?”

This is where policy design enters the picture. Bali and Ramesh draw on policy design literature to show that crafting effective policy requires attention to a specific set of design attributes. These attributes act like quality checks. If they’re not met, the policy is likely to underperform, no matter how “strong” the state is in general.

They explain:

On one hand, there is a need for increased capabilities for governments to maneuver a rapidly changing policy terrain. The rise of plurilateral, collaborative, and ‘meta governance’ styles is fundamentally changing the extent to which, and how, governments interact with stakeholders in the provision of public goods and services. The contemporary policy environment is characterized by increased economic and political uncertainty; continual technology disruptions that fundamentally change how a problem is conceptualized (let alone addressed); and the growing complexity of modern problems underscore the importance of creating agile, informed, and resilient designs. Adding to this are growing expectations of citizens in increasingly contestable societies that their governments will play a larger role in the provision and financing of positional goods, and help manage risks that were previously addressed largely by the market. However, on the other hand, many country-specific studies have documented, and many governments have acknowledged, the gradual decline in capacity over the years. As early as the mid-1990s, scholars attributed this decline to the gradual ‘hollowing out’ of government, fueled by a series of public management reforms which emphasized fragmentation, contracting out, and the unfettered pursuit of economic efficiency in the delivery of public services. This seeming contradiction, of the need for greater policy capacity and the gradual decline in skills and competencies, can be addressed by applying the design orientation or problem-solving approach central to the policy sciences to policy capacity. As opposed to platitudes on the need for capacity building, it would require responding to ‘what skills and competencies are required to be able to address, or at least mitigate, the given problem at hand’. This not only requires being able to conceptualize the problem in its constituent elements, generate plausible solutions, ensure that they are politically viable, and can be implemented, but will require designers to be cognizant of the design attributes that increase the effectiveness of a given policy or program.

Here are the nine attributes they identify, each of which corresponds to common real-world challenges:

Coordination

Emphasizes the need to see the bigger picture—to ensure that new policies align with and complement existing ones. Without this, policies often overlap or conflict. For example, in Ghana, residents once held up to seven different national ID cards, creating inefficiency and confusion. In India, the RSBY health insurance scheme was run by the Ministry of Labour without proper coordination with the Ministry of Health, leading to duplication and gaps. Good coordination means policy changes should be made with awareness of how they affect other programs and actors, avoiding unintended disruptions.

Coherence

This attribute is about making sure that different policies work well together and support a common goal. It means that government actions across various departments should be aligned, not pulling in different directions. For example, if multiple programs are aimed at the same group, like farmers or low-income families. They should be based on similar ideas and not confuse or contradict each other.

Over time, small changes to policies—like adding new rules or tweaking old ones can unintentionally weaken this alignment. These changes might shift the focus, create mixed messages, or change incentives in ways that reduce the overall effectiveness.

Just like coordination, maintaining coherence requires looking at the bigger picture: Are the policies targeting the same beneficiaries in consistent ways? Do they reflect the same goals and principles? And are both the substance of the policies and the processes used to implement them working in harmony?

Goodness of Fit

This attribute means that a policy should be well-suited to the specific context in which it is being implemented. This includes the nature of the sector, like health, education, or energy, as well as how decisions are usually made and what the political environment looks like.

In simple terms, a policy design that works well in one place might not work the same way elsewhere. For example, a highly centralized program might work in a country with strong top-down governance, but not in one where power is more decentralized.

So, a good policy needs to “fit” its surroundings; it should match the way things are governed, the capacity of institutions involved, and the political realities on the ground. If it doesn’t, even a well-intentioned policy can fail.

Consistency

This attribute means that all the tools and actions used in a policy should support the same goal and not work against each other. Problems arise when some parts of a policy give positive signals (incentives) while others send mixed or negative signals (disincentives), making it harder to achieve the intended outcome.

Think of it like trying to drive a car while pressing the accelerator and the brake at the same time; progress becomes difficult or confused.

Scholars like Howlett and Rayner explain that coherence is about aligning the goals of a policy, while consistency is about aligning the methods or tools used to reach those goals. When policy tools are inconsistent, it can cause policies to slowly shift or “drift” away from their original purpose, or get layered with new, sometimes conflicting elements. This weakens the effectiveness of the policy over time. Research also shows that sudden and major changes in how a policy is carried out can negatively affect results.

Degrees of Freedom

The Degrees of Freedom attribute refers to how much flexibility policy designers have to make changes in the future. In reality, most policies aren’t created from scratch; they build on past decisions. Over time, adjustments like adding new rules or modifying old ones can limit future options. That’s why it’s important to design policies in a way that leaves room for future updates, allowing both small tweaks and bigger shifts as situations change.

Complementarity

This attribute is about making sure that different parts of a policy work well together and strengthen each other. It’s not enough for policies to simply avoid conflict—they should create positive effects when combined.

For example, one tool might improve service delivery, while another boosts accountability. If used together in the right way, they can reinforce each other and make the policy more effective.

So, when designing policies, it’s important not only to ensure coordination and coherence but also to actively look for synergies—ways in which different tools can support and enhance one another. Ignoring this can lead to wasted resources or unintended negative effects.

Targeting

The targeting attribute is about how well a policy reaches the people it's meant to help, without including those who shouldn’t receive the benefits.

There are two common problems:

Exclusion errors: when people who should get the benefits are left out.

Inclusion errors: when people who aren’t eligible receive the benefits.

From a policy design point of view, the goal isn’t just to avoid one type of error, but to reduce both as much as possible. Good design means thinking carefully about how these mistakes can happen and putting systems in place to minimize them, like better data, clear eligibility rules, and strong delivery mechanisms.

Reversibility

The reversibility attribute is about how easily a policy or its parts can be changed or rolled back in the future. While similar to flexibility (or degrees of freedom), reversibility focuses on how big the change is and whether it’s politically possible.

In large countries like India or Brazil, reversing a policy that affects millions, like subsidies, can be very difficult, both financially and politically. Once people start benefiting, it creates pressure to keep the program going, even if it’s no longer effective.

That’s why good policy design should plan ahead—for example, by including a sunset clause (an expiry date) or setting clear limits on cost or scale to make future changes easier.

Contingency

The contingency attribute is about planning for future risks and unexpected costs that may arise from a policy, known as contingent liabilities. These are costs the government might have to cover later, like pension shortfalls, healthcare demands, or even bank bailouts.

The challenge is that many governments underestimate these risks, and once the policy is in place, it becomes hard to add safeguards later because beneficiaries may resist changes.

Good policy design doesn't have to eliminate all future costs, but it should include ways to manage them from the start, like setting aside reserves, adding spending limits, or building in flexible rules, so the government isn’t caught off guard.

Mapping Capacity: A Multi-Level Framework

Now that we know what good design looks like, the question becomes: who needs to be capable of doing what, and at what level?

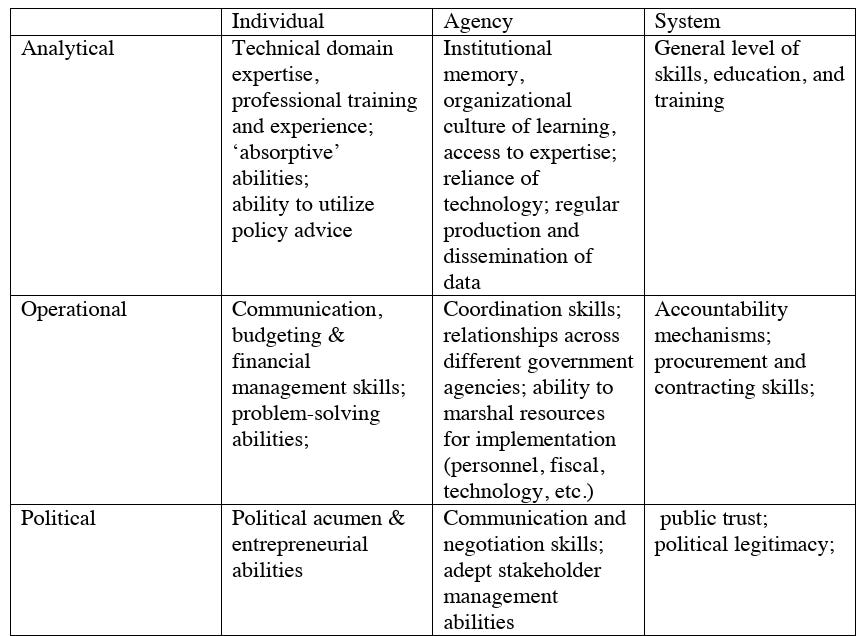

This is where one of the paper’s most useful contributions comes in: a three-by-three matrix that organizes policy capacity by type (analytical, operational, political) and level (individual, organizational, systemic).

Let’s walk through it:

This framework helps explain why policy failure is often not just about bad ideas or poor execution, but mismatched or missing capacities. For example:

A good policy can fail if there’s not enough political buy-in (low political capacity).

A creative policy design might be unworkable if procurement systems are broken (weak operational capacity).

A well-funded reform might collapse if bureaucrats don’t know how to adapt it to local realities (poor analytical capacity).

The real insight here is that capacities must match the demands of policy design. If a policy requires coordination across sectors, but the system lacks inter-agency collaboration mechanisms, the design will break down. If a reform depends on citizen trust, but the state lacks legitimacy, the best-designed policy will still stumble.

A Case in Point: Health Policy Design

One of the biggest challenges in health policy, especially in developing countries, is how to ensure that people have access to quality healthcare without falling into financial hardship. In much of Asia, healthcare costs are still largely paid out of pocket by households. To tackle this, many governments have introduced reforms aimed at achieving universal health coverage (UHC). These reforms typically involve two key strategies: increasing public financing (such as through government-funded insurance) and expanding public provision (often by contracting private healthcare providers).

While these reforms are well-intentioned, evidence shows that they often fall short. Why? Simply pouring more money into the system or adding new delivery mechanisms does not automatically solve the deeper, structural problems that exist within the healthcare sector. These include things like:

Information asymmetry (where patients don’t have enough knowledge to make informed choices),

Moral hazard (where insured individuals or providers overuse services),

Weak accountability, and

Fragmented delivery systems.

Bali and Ramesh argue that unless these underlying governance issues are addressed through careful design, health reforms will not lead to meaningful improvements in access, quality, or outcomes. They emphasize the importance of designing appropriate governance arrangements that manage the complex web of relationships between key actors—patients (users), healthcare providers, insurers or payers, and the government (the state).

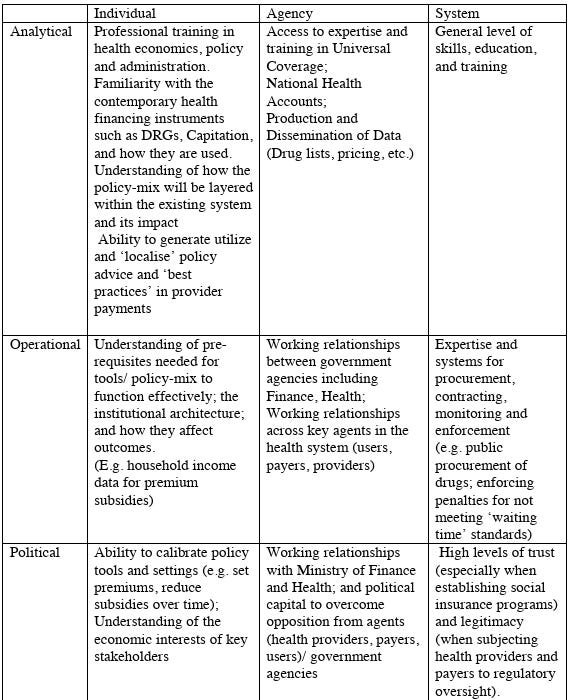

To guide this process, the authors apply their policy design framework to the health sector. Using the table below, they map out the different tasks involved in designing health policies and how these link to specific types of capacity.

1. Analytical Design Tasks: Understanding the Problem and Finding the Right Tools

Designing effective health policy starts with understanding what exactly is going wrong. This involves:

Breaking the problem into parts, such as identifying the specific causes of high costs or poor access,

Diagnosing issues like perverse incentives among providers (e.g., overprescribing, unnecessary tests),

Generating evidence to identify what types of policy tools (health financing instruments like DRGs, i.e., Diagnosis-Related Groups or capitation) could address these problems, and

Designing tools that encourage providers and payers to behave in ways that improve efficiency and fairness.

This level of design work requires deep analytical capacity, knowledge of economics, public health, and policy tools, as well as the ability to interpret and localize best practices for the national context.

2. Operational Design Tasks: Making It Work on the Ground

Even the best-designed policy ideas won’t succeed without solid planning and execution. This part of the design process involves:

Ensure that the prerequisites for each tool are in place. For example, if the policy depends on subsidizing premiums for low-income families, accurate income data must be available.

Coordinating between different government departments, like Health and Finance, to make sure that the policy is coherent and fits with existing programs.

Establishing accountability systems, such as contracts that define standards for private providers, or penalties for non-compliance.

Operational capacity is often where health reforms falter, particularly when public systems lack procurement skills, reliable data systems, or inter-agency cooperation.

3. Political Design Tasks: Managing Stakeholders and Building Support

Health reforms are politically sensitive. They affect millions of people and often challenge entrenched interests, such as private hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, or existing bureaucracies. Therefore, a key part of design is political:

Identifying potential resistance from key stakeholders (e.g., providers who might lose income),

Negotiating trade-offs and building coalitions to support the reform,

Communicating the purpose and benefits of the policy to the public and key actors to generate buy-in,

Navigating the reform through the political system, including legislative or cabinet approval.

This requires political capacity, the ability to read the landscape, engage with interest groups, and adjust the design in politically realistic ways.

4. Skills and Competencies: Who Needs What Capacity?

In the table below, the authors further break down what types of skills and capacities are needed at different levels of the system, individual, agency, and system-wide.

At the individual level, health policy designers need technical training in areas like health economics and insurance design, along with a practical understanding of tools like DRGs or capitation.

At the agency level, departments need access to expertise in managing large-scale programs, inter-departmental collaboration, procurement, contracting, and monitoring.

At the system level, the broader environment must support high-quality data, trust in public institutions, and a general level of legitimacy so that regulations are followed and reforms are accepted.

What this case study shows is that no amount of funding or political will alone can fix health systems. Without the right capacities in the right places, policies will either fail to launch or stumble during implementation. At the same time, even modest reforms can have a significant impact if they are well-designed and supported by the necessary skills and systems.

In the end, the authors argue that health reforms, like all complex policies, must be treated as design problems that require strategic investments in capacity. This means thinking carefully not just about what to do, but how to do it, who will do it, and whether they are equipped to succeed.

If policy is a craft, then this paper is a guide to the tools that make it work. It brings conceptual clarity, practical insights, and a powerful reframing: capacity is not a generic virtue. It is a design imperative.

Governments that succeed in the future will be those that can design wisely, implement realistically, and adapt politically. That means not just hiring smarter people or buying better software, but investing in the distributed, layered capacities that allow policy systems to learn, adapt, and hold together under pressure.

For policymakers, scholars, and practitioners alike, Bali and Ramesh offer more than a framework. They offer a way to think, and that, too, is a form of capacity.

Great article. Could you please suggest some introductory non-fiction/ textbooks to understand the basic of public policy?