Dispatch #105: Escaping the middle-income trap

In this dispatch, we explore the World Development Report 2024 and its insights on the middle-income trap.

For many nations, transitioning from poverty to middle-income status is often seen as a big achievement. It signals a nation's ability to utilize its resources, leverage its workforce, and build a robust economy to uplift millions from destitution. But this ascent, as history has shown, is fraught with challenges. The real test begins after crossing into middle-income territory. Many countries find themselves stagnating, unable to leap to high-income status. This economic standstill is what economists call the "middle-income trap."

The 2024 World Development Report (WDR 2024) delves deep into this phenomenon, analyzing why some nations continue their upward trajectory while others remain stuck in the middle. India, which entered middle-income status in 2007, now stands at a critical juncture. Will it overcome the obstacles that have stalled growth in other nations, or will it find itself trapped like much of Latin America and the Middle East? To answer this, we must examine the nature of the middle-income trap, India's current position, and the crucial steps needed to escape stagnation.

The Middle-Income Trap: A Growth Killer

The term "middle-income trap" was first introduced by the World Bank in 2007 to describe a common economic pattern: Countries initially grow fast due to cheap labor, capital investment, and integration into global supply chains. However, as wages rise and the low-hanging economic fruits are exhausted, growth slows. The real game-changer—innovation—does not always follow naturally. If countries fail to transition from efficiency-driven to innovation-driven economies, they stagnate, caught in a perpetual cycle of moderate growth, rising inequality, and economic instability. The WDR 2024 classifies 108 countries as middle-income countries - those with annual per capita incomes ranging between USD 1,136 to USD 13,845.

The WDR 2024 explains this nuance beautifully:

You are a policy maker in one of the world’s 108 middle-income countries. You have learned the importance of creating a credible, solid macroeconomic foundation for private investment, domestic and foreign, supported by strong institutions and clean governance. And, like Deng Xiaoping nearly 50 years ago, quoted here, you have big plans. If your country is China, your 14th Five-Year Plan envisions reaching the median gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of developed nations by 2035, thereby greatly expanding your middle class. If it is India, your prime minister’s vision is to turn the nation into a developed economy by 2047, the centennial of independence. If it is Vietnam, your Socio-Economic Development Strategy 2021–2030 outlines a strategy for sustained GDP per capita growth of 7 percent through this decade, with a transition to high-income status by 2045. And if it is South Africa, your 2030 National Development Plan sets a goal of raising the income per capita from US$2,800 in 2010 to US$7,000 by 2030. Other middle-income countries have similar aspirations. If these plans succeed, your country will reach high-income status in less than one generation, or in one or two. Your firms will be earning like never before. Your people will be consuming like never before. Far fewer people will be poor, with none desperately poor. In the halls of government, these plans generate tremendous optimism. But there is a problem. According to widely used measures such as the World Bank’s World Development Indicators, you see that economic growth in middle-income countries—including your own—is not accelerating. If anything, it is slowing down as incomes increase—and even more so every decade.

Several countries provide stark examples. Many Latin American economies have been stuck in middle-income status for decades due to weak industrial bases, sluggish innovation, and governance inefficiencies. Similarly, parts of the Middle East, despite resource wealth, have struggled to diversify their economies beyond oil and gas. In contrast, nations like South Korea and Taiwan managed to leap from middle-income to high-income status by investing heavily in education, technology, and high-value industries. This begs the question: Where does India stand, and what must it do differently?

i,2i and 3i framework and economics of creative destruction

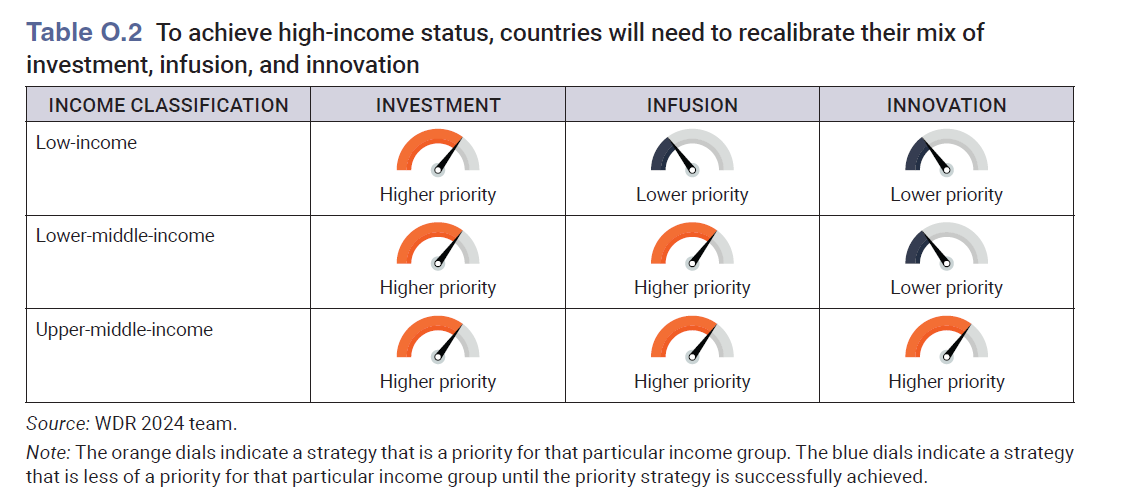

The WDR 2024 introduces the framework of i, 2i, and 3i, a structured approach that outlines how economies evolve through different stages of development.

At the most fundamental level, the i stage is all about investment. Low-income countries focus on attracting capital, developing infrastructure, and ensuring that businesses have the necessary resources to grow. The primary challenge here is to create an environment conducive to investment, often by improving governance, ensuring macroeconomic stability, and facilitating foreign direct investment.

As economies transition into the 2i stage, investment alone is no longer sufficient; they must also infuse global knowledge into their industries. Lower-middle-income countries need to integrate into global value chains, adopt cutting-edge technologies, and bring in best practices from around the world. This requires strengthening regulatory frameworks, improving workforce skills, and opening up markets to healthy competition. The infusion of external expertise allows businesses to become more efficient, making them competitive on a global scale.

The final stage, 3i, is where countries not only invest and infuse knowledge but also innovate. Upper-middle-income economies must go beyond mere adoption of external technologies and start generating their own. This means investing in research and development, creating strong linkages between industry and academia, and fostering an entrepreneurial culture that rewards risk-taking and creativity. At this stage, economic growth is driven by innovation, where businesses are not just adapting to global trends but shaping them. Countries that successfully transition into this phase become global leaders in technology and industry.

The concept of creative destruction is central to understanding how economies evolve, balancing progress with disruption. First introduced by Joseph Schumpeter in his seminal work Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (1942), creative destruction describes the process by which innovations, industries, and business models replace outdated ones. While this cycle drives economic growth and technological advancement, it is also inherently disruptive, as it displaces old industries, restructures labor markets, and forces societies to adapt to continuous change.

At its core, creative destruction is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it fosters progress by pushing societies toward more efficient and innovative ways of producing goods and services. On the other, it leads to job losses, business failures, and social upheaval as old industries collapse under the weight of new competition. This makes creative destruction a dynamic but also contentious force in economic development.

The WDR 2024 examines three key perspectives on how creative destruction unfolds in economies, each highlighting different actors and forces that shape this process.

The first perspective, drawn from Schumpeter’s original theory, focuses on how incumbents resist change. Large, established businesses and industries, recognizing that innovation threatens their market dominance, often engage in rent-seeking behavior, lobbying governments to impose regulations or barriers that protect them from competition. This is particularly visible in the energy sector, where fossil fuel companies have historically worked to delay the adoption of renewable energy. Rather than embracing the transition, they use their influence to slow down regulatory changes and maintain their profitability. This resistance can be seen in many industries where monopolies or oligopolies dominate, from pharmaceuticals to telecommunications, where powerful incumbents try to shape policies in their favor.

The second perspective, developed by Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, shifts the focus to new entrants as the primary drivers of growth. According to this view, creative destruction is a process in which startups and smaller firms disrupt the dominance of established players through breakthrough innovations. This dynamic is most evident in the technology sector, where new firms rapidly scale up and replace legacy businesses. Consider how streaming services such as Netflix displaced traditional cable television or how ride-sharing platforms like Uber and Ola disrupted the traditional taxi industry. The key argument here is that economies thrive when barriers to entry are low, allowing entrepreneurial firms to challenge incumbents and introduce innovations that benefit consumers and society.

The third perspective, put forward by Ufuk Akcigit and William Kerr, presents a more nuanced and balanced view. Unlike Schumpeter, who saw incumbents as obstacles to progress, and Aghion and Howitt, who emphasized disruptive new entrants, Akcigit and Kerr argue that both incumbents and new firms contribute to economic growth. Large corporations, rather than resisting change, can also be sources of innovation. Many established firms invest heavily in research and development, acquiring startups or integrating new technologies into their operations to stay competitive. Apple, for instance, continually innovates by developing new products while also acquiring smaller technology firms that bring fresh ideas into its ecosystem. Similarly, companies like Google and Microsoft actively fund AI research and new technology startups, blending internal innovation with external acquisitions.

These three views together paint a comprehensive picture of creative destruction. While some firms and industries resist change, others drive it, and in many cases, both incumbents and new entrants work in tandem to transform economies. The challenge for policymakers is to strike a balance—creating an environment where innovation is encouraged while also managing the disruptive effects of economic transformation. Governments must support displaced workers through retraining programs, provide social safety nets, and ensure that market competition remains fair and open.

In this sense, creative destruction is not just an economic theory but a real-world phenomenon that affects millions of people. It determines which industries thrive, which decline, and how societies adapt to technological shifts. The WDR 2024 highlights that while creative destruction is necessary for long-term economic growth, it must be managed carefully to ensure that progress does not come at an unmanageable social cost. The economies that navigate this process successfully are those that embrace innovation while also fostering resilience and adaptability among their workforce and institutions.

The report explains how South Korea deployed this framework to transition into a high-income country:

Korea’s success may be the best support for the argument that sustaining high growth requires adding infusion to accelerations of investment, and then again augmenting the 2i mix with innovation policies. Korea was among the least developed countries globally in the early 1960s, with income per capita of less than US$1,200 in 1960. By 2023, after an unparalleled five-decade run of high output growth, Korea’s income per capita had risen to about US$33,000. In the 1960s, a combination of measures to increase public investment and encourage private investment kick-started growth. In the 1970s and 1980s, Korea’s growth was powered by a potent mix of high investment rates and infusion, aided by an industrial policy that encouraged firms to adopt foreign technologies. Firms received tax credits for royalty payments, and family-owned conglomerates, or chaebols, took the lead in copying technologies from abroad—primarily Japan. As Korean conglomerates caught up with foreign firms and encountered resistance from their erstwhile benefactors, industrial policy shifted toward a 3i strategy supporting innovation. Then, as Korean firms became more sophisticated in what they produced, they needed workers with specialized engineering and management skills. The Ministry of Education, through public universities and the regulation of private institutions, did its part, setting targets, increasing budgets, and monitoring the development of these skills. These firms also required more specialized capital: for a growing middle-income economy, investment remained important.

India’s Growth Story: Sprint or Stumble?

India’s economic rise has been remarkable. Since liberalization in the 1990s, the country has transformed into one of the world’s fastest-growing major economies. Government initiatives such as Make in India, Digital India, and Startup India have aimed to position the country as a global leader in manufacturing and technology. However, despite impressive GDP growth, warning signs have emerged.

The biggest challenge India faces is the inability to scale up its manufacturing sector. Unlike China, which leveraged manufacturing to generate mass employment and drive economic growth, India’s industrial sector remains underdeveloped. Millions of workers remain trapped in informal, low-paying jobs, and the country’s ease of doing business continues to suffer due to bureaucratic inefficiencies.

Another pressing issue is India's workforce. While the nation boasts a vast youth population, a significant portion lacks the skills required for a rapidly evolving job market. The mismatch between education and industry needs has left many young people unemployed or underemployed. Moreover, India’s investment in innovation remains weak. The country lags behind South Korea and China in research and development (R&D) spending and patent filings. Without significant investments in cutting-edge technology, India risks becoming a consumer of global innovations rather than a creator. Lastly, climate change presents an existential challenge. As India industrializes, balancing economic growth with environmental sustainability will be critical. A growth model that prioritizes green energy, sustainable urban planning, and climate resilience is essential to ensuring long-term progress.

Can India Escape? The Three-Stage Plan

The WDR 2024 proposes a three-step strategy for middle-income countries seeking to break free from stagnation: Investment, Infusion, and Innovation. These steps are not just theoretical concepts but essential pillars for India’s economic future.

1. Investment: Laying the Groundwork

India has poured billions into infrastructure projects, from highways and airports to digital connectivity. While these developments are necessary, they are not sufficient. The real challenge is attracting private investment. Businesses still struggle with bureaucratic red tape, land acquisition hurdles, and inconsistent policy frameworks. Cutting regulatory bottlenecks and ensuring a stable business environment is crucial to unlocking a wave of private sector investment.

Financial markets also need reform. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs), which drive employment and innovation, often struggle to access capital. Strengthening banking systems, expanding venture capital funding, and promoting fintech solutions could significantly boost entrepreneurial activity. Investment, however, must go beyond financial capital—it should also focus on making cities more liveable, efficient, and productive economic hubs.

2. Infusion: Borrowing the Best Ideas

The second step is embracing global knowledge and technologies. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) plays a crucial role here, but India needs to make itself more attractive to global firms. Reducing trade barriers, ensuring policy consistency, and fostering international collaborations can accelerate technology transfer.

Education reform is another crucial area. India’s young workforce can be a demographic dividend or a liability, depending on how well it is trained. Strengthening STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) education, expanding vocational training, and aligning university curricula with industry demands will help India develop a future-ready workforce.

Additionally, digital transformation must be prioritized. Expanding broadband infrastructure, promoting AI-driven industries, and enhancing digital literacy will ensure that India is not just a consumer of technology but a global leader in its application and development.

3. Innovation: Leading the Charge

The final and most challenging stage is transitioning from an efficiency-driven to an innovation-driven economy. India must boost R&D spending to at least 2% of GDP and create policies that encourage businesses to invest in new technologies. Strengthening intellectual property rights and simplifying patent laws will further incentivize homegrown innovation. India’s startup ecosystem has shown promise, but sustaining momentum requires tackling funding constraints and reducing bureaucratic friction. High-tech sectors such as semiconductors, biotechnology, and AI present massive opportunities—provided the right policies and incentives exist.

Risk-taking must also be encouraged. A robust venture capital ecosystem and access to early-stage funding can help convert ambitious ideas into viable businesses. India has the talent and entrepreneurial drive; now, it needs an ecosystem that nurtures rather than stifles innovation.

The report explains:

To achieve more sophisticated economies, middle-income countries need two successive transitions, not one. In the first, investment is complemented with infusion, so that countries (primarily lower-middle-income countries) focus on imitating and diffusing modern technologies. In the second, innovation is added to the investment and infusion mix, so that countries (primarily upper-middle-income countries) focus on building domestic capabilities to add value to global technologies, ultimately becoming innovators themselves. In general, middle-income countries need to recalibrate the mix of the three drivers of economic growth—investment, infusion, and innovation—as they move through middle-income status.

India's economic journey, as captured in the WDR 2024, is one of remarkable progress, balancing investment-driven expansion with an evolving push toward innovation. The report situates India within the i, 2i, 3i framework, highlighting how the country has moved from an investment-led economy to one that actively integrates global knowledge and now aspires to establish itself as a hub of innovation. However, it also underscores the challenges that India faces in sustaining long-term growth, particularly in fostering a competitive business environment, strengthening domestic innovation, and navigating the forces of creative destruction.

For decades, India's economic growth has been fueled by heavy investments in infrastructure, manufacturing, and digital transformation. Public and private sector spending has expanded access to roads, electricity, and telecommunications, creating the foundation for industrial expansion. The Indian IT industry serves as a prime example of how investment and global knowledge infusion can drive an entire sector’s rise. Companies such as Infosys, Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), and Wipro harnessed India's engineering talent pool, collaborated with global clients, and adopted best practices from advanced economies to build an industry that now generates billions in revenue annually.

However, despite these successes, the report highlights that India still struggles to make the full transition to an innovation-driven economy. Much of the technological advancement in India has been imported or adapted from global markets rather than developed domestically. While Indian firms have excelled in process innovation—optimizing existing technologies and making them more cost-effective—they have not yet emerged as global leaders in cutting-edge innovation, such as artificial intelligence, biotechnology, and advanced manufacturing. The report attributes this to low investment in research and development (R&D), limited collaboration between academia and industry, and restrictive business policies that make it difficult for startups to scale.

Creative Destruction in India: A Work in Progress

As seen above, one of the most significant themes of the WDR 2024 is creative destruction, a process in which new ideas, firms, and industries disrupt traditional ways of doing business, leading to economic renewal. In the Indian context, creative destruction has played out unevenly across sectors.

The IT and software services sector exemplifies how new firms and emerging technologies have successfully challenged older business models. In the 1980s and 1990s, young, ambitious companies like Infosys and HCL disrupted the traditional Indian business landscape, proving that global success was possible outside of state-run enterprises and family-owned conglomerates. These firms competed with global giants, built offshore outsourcing models, and positioned India as the back office of the world.

However, in other sectors, particularly manufacturing, retail, and energy, the forces of creative destruction have been slower to take effect. Many large Indian businesses continue to dominate due to protectionist policies, regulatory bottlenecks, and difficulties faced by smaller firms in accessing capital. In industries such as steel, textiles, and telecommunications, incumbents have leveraged government relationships and complex regulations to retain their market dominance, making it harder for new entrants to challenge them.

The report identifies three key perspectives on creative destruction and applies them to India’s case. From Schumpeter’s perspective, large Indian firms actively resist disruption by influencing regulatory policies to limit competition. This has been seen in sectors such as telecommunications, where established players have pushed for policies that favor their market position over new competitors.

From the Aghion and Howitt perspective, India's startups and new businesses have emerged as the primary drivers of change, particularly in the digital economy. The rise of FinTech companies like Paytm, PhonePe, and Razorpay demonstrates how innovative firms have challenged traditional banking and financial models, forcing legacy institutions to adapt.

The Akcigit and Kerr perspective, which suggests that both new entrants and incumbents contribute to economic progress, is reflected in sectors where large firms coexist with smaller disruptors. A notable example is the automobile industry, where companies like Tata Motors and Mahindra have successfully integrated electric vehicle startups and global clean energy innovations into their business strategies.

The Challenges That India Must Overcome

While India’s economic transformation has been impressive, the report identifies several structural challenges that threaten to slow down progress. One of the most significant barriers to innovation is the low level of R&D investment. Compared to global leaders like the United States and China, India spends significantly less on research and technology development, making it harder to generate breakthrough innovations. The lack of university-industry collaboration further exacerbates this issue, as many academic research outputs do not translate into marketable products or commercial ventures.

Another major concern is the difficulty that small and medium enterprises (SMEs) face in scaling up. Despite India’s reputation as a startup powerhouse, many young firms struggle to grow beyond a certain level due to bureaucratic red tape, high costs of credit, and restrictive labor laws. This limits the full potential of creative destruction, as smaller firms often lack the resources to challenge established players.

Moreover, the report warns about policy uncertainty, which can stifle investor confidence. Over the years, shifts in taxation, foreign investment regulations, and industrial policies have made it difficult for businesses to plan long-term investments. To foster an innovation-friendly business environment, the government needs to create clear, stable, and transparent policies that encourage risk-taking and entrepreneurship.

The WDR 2024 concludes that India stands at a critical inflection point in its economic evolution. It has successfully built a strong foundation through investment and knowledge infusion, but the next phase of growth requires deepening its innovation ecosystem and addressing structural challenges.

For India to emerge as a true global leader in innovation, it must reform business regulations, strengthen R&D investment, and foster an environment that allows creative destruction to unfold more dynamically. The government needs to play a crucial role in ensuring that both large incumbents and new entrants contribute to economic progress, rather than allowing entrenched players to stifle competition. At the same time, investment in education, skill development, and research must increase to ensure that the workforce is prepared for the demands of a rapidly changing economy.

Got to know about creative destruction. The 3 stages - investment, infusion, and innovation. India being a middle income country needs to fuse the three.

I also feel infusion is something that is still a dream because there is no collaboration between industry and academia.

Bookmarked this one.and subscribed! Looks interesting!