Dispatch #106: Why public policy students need public choice theory—Even if they don’t like it

This post explores why public choice theory—despite its relevance to real-world governance—remains missing or misunderstood in public policy curricula.

I’ve been teaching public policy for several years now, to students of varying backgrounds: mid-career bureaucrats, development sector professionals, fresh graduates. Over time, I’ve grown increasingly drawn to public choice theory as a framework for understanding how governments operate—not as abstract entities, but as networks of individuals driven by incentives. It helps explain many dysfunctions we observe in real-world governance: why bureaucratic inefficiencies persist, why electoral cycles shape policy priorities, and why even well-designed schemes falter in implementation.

But whenever I introduce the key ideas of public choice theory, many students react with confusion or discomfort. Some are uncomfortable with the thought that government officials might act in their own self-interest. Others find it hard to question the intentions of public institutions. This reaction isn’t just about understanding the theory—it feels personal. It made me pause and ask: why does public choice theory provoke such strong responses? And why isn’t it a bigger part of public policy and development education, especially in India, where its ideas seem highly relevant?

This post is an attempt to answer that question.

The idea that public servants might act in their own self-interest, or that institutions can amplify rather than solve problems, often surprises students. To many, it sounds overly negative or detached from the values that drew them to public service in the first place. They've been raised—intellectually and often morally—on stories of public servants as selfless change-makers and the state as a force for good. Many see the state and its functionaries not just as administrators, but as noble agents of societal progress.

These beliefs are deeply embedded, not just through formal education, but through media portrayals, civic textbooks, and public discourse. In India especially, the high stature and reverence accorded to public servants—through exams, ceremonial roles, and everyday narratives—has contributed to a near-mythic image of the state as a benevolent force. This idealization shapes how many students approach policy and governance, often making them resistant to frameworks that suggest otherwise.

Many who enter the public policy and development sector do so with a strong sense of purpose and idealism. They often imagine the state as the primary engine of development and social justice, and its functionaries as sincere agents of transformation. This belief is understandable, given the historical context of post-colonial nation-building and the central role the state has played in shaping developmental narratives, especially in countries like India. So when I present public choice theory’s core argument—that state actors are also shaped by incentives, just like anyone else—it feels jarring. It clashes with their inner image of how governance works.

This discomfort, I’ve come to realize, is part of why public choice theory has not found a stronger foothold in public policy and development studies, especially in India but also globally.?

A Quick Primer on Public Choice

Public choice theory, most commonly linked with James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock, changed how we think about politics and government. Instead of assuming that politicians, bureaucrats, and voters are always motivated by the public good, it suggests they behave much like people in the marketplace—guided by personal goals, incentives, and constraints. It borrows from economics the idea that people act in their own self-interest, and applies it to politics. As Buchanan explained in his 1986 Nobel lecture, public choice theory doesn’t aim to attack or discredit the state. Rather, its goal is to make sense of how decisions are really made in politics and government, not just how we hope they are made.

Instead of assuming that governments always act in the public interest, public choice theory poses more empirical and behavioral questions: What do public actors actually do, and why? What incentives shape their choices? What institutional rules guide or distort their behavior? For example, why do bureaucracies grow even when efficiency suffers? Why do politicians favor short-term populist measures over long-term planning? Why are certain groups able to secure disproportionate policy benefits? These are the questions at the heart of public choice.

William Niskanen's model of the budget-maximizing bureaucrat in the 1970s offered one such answer—suggesting that bureaucrats often push for larger budgets not out of concern for public welfare, but because their power and prestige are tied to the size of their department.

Mancur Olson, in his influential book "The Logic of Collective Action," argued that individuals in large groups have little incentive to act in the collective interest because the benefits of such actions are shared by all, regardless of individual contribution. As a result, larger groups tend to suffer from free-rider problems and are less likely to organize effectively. In contrast, small, well-organized special interest groups can exert disproportionate influence over public policy because they can coordinate action more easily and the benefits of lobbying efforts are more concentrated. This helps explain why policies often cater to narrow interests at the expense of the broader public.

Buchanan and Tullock, in "The Calculus of Consent," added to this by examining how collective decision-making within democratic institutions involves trade-offs between the need for consensus (which enhances legitimacy) and the need for efficiency (which ensures decisions are made in a timely manner). Together, these works underscore how structural incentives and group dynamics shape political outcomes in ways that often diverge from the ideal of equal representation or public good maximization. Taken together, these contributions form a body of thought that reorients our understanding of governance—from a moral enterprise to an institutional process shaped by incentives, information gaps, and human limitations.

Take the concept of the budget-maximizing bureaucrat, introduced by William Niskanen in the 1970s. Niskanen argued that bureaucrats are not always motivated by a pure desire to serve the public interest. Instead, they often aim to maximize the size of their agency's budget, since their influence, prestige, and sometimes even salary are linked to how large and powerful their department is. This leads to over-expansion of government programs and inefficiencies, as bureaucrats push for more funding and staff even when it's not needed. Alongside this, elected officials often implement short-term, vote-winning policies before elections rather than focusing on long-term public good. And then there's rent-seeking—when special interest groups lobby for regulations that benefit them at the expense of the broader public. All of these are public choice problems, revealing how personal incentives can distort public decision-making.

Yet despite its real-world relevance, public choice remains a minor player in most public policy curricula.

The Bias Toward Idealism

One major reason for this is ideological discomfort. In many post-colonial societies like India, public policy education often starts with an idealized image of the state. The government is viewed as a noble force working for the public good—correcting market failures, protecting the vulnerable, and advancing justice. This belief is shaped by historical narratives of nation-building, where the state played a central role in development, as well as by the high status given to public servants through civil service exams, media portrayals, and cultural respect. Because of this, questioning whether the state could be misused by elites or driven by self-interest often feels wrong or disloyal. It challenges deeply held assumptions, not just about how the government works, but about its very purpose and values.

The Indian state, in particular, has long been viewed as the central engine of social and economic transformation. This is understandable—given the history of colonial exploitation and the promises of planned development. But it creates an intellectual environment where critiques of the state are dismissed as right-wing or neoliberal.

James Buchanan himself faced this. In his Nobel Prize lecture (1986), he recalled how even fellow economists saw his work as subversive, as it questioned the morality of collective political action. He was not trying to delegitimize the state—but simply to bring the same analytical clarity to government that economists had long applied to markets.

Students Want Heroes, Not Models

Another challenge is related to how we teach public policy. Public choice theory encourages students to move away from judging government actions purely on moral grounds and instead think in terms of real-world behaviors and incentives. For instance, rather than asking, "Is this welfare scheme fair or just?" it prompts students to ask more practical questions like: "What motivates the bureaucrats running the scheme? Are they promoted based on the impact they create or the amount they spend? Are there rewards for efficiency or just for following procedures?" It also invites analysis of how voters perceive and respond to such schemes—do they vote based on short-term benefits or long-term results? This way of thinking requires a shift from idealism to realism, which can be uncomfortable for students who are used to seeing public service as a space of noble intentions.

This shift in thinking can be confusing and unsettling. Many students come into public policy programs deeply motivated by values like equality, justice, and sustainability. They see policy work as a way to make the world better. Public choice theory, in contrast, asks them to look at government through a more analytical and sometimes uncomfortable lens. It suggests that public officials and institutions might be influenced more by personal incentives than by public ideals. To students, this can feel emotionally distant, overly analytical, or even pessimistic—like it’s taking the heart out of public service.

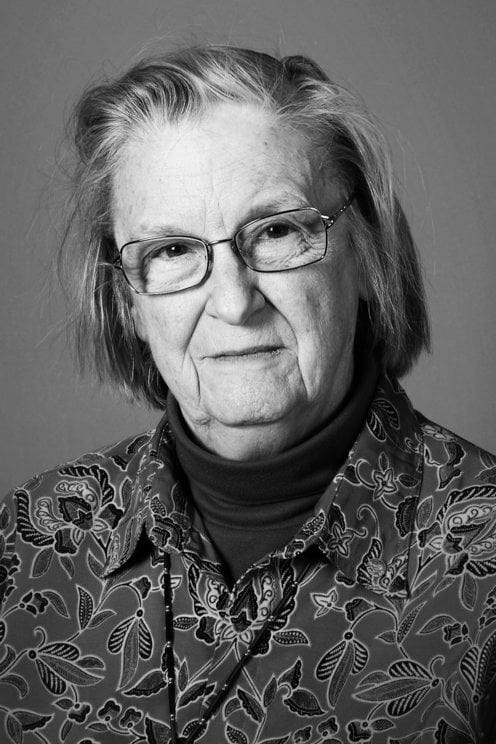

As Elinor Ostrom—who expanded and nuanced public choice theory—often emphasized, the key to building functional institutions lies in understanding how people actually behave, not how we wish they would. Designing systems around saintly behavior is a recipe for collapse.

A Western Theory?

A third reason for public choice’s marginalization is that it is often seen as Western or culturally inappropriate. After all, the seminal texts—The Calculus of Consent, The Logic of Collective Action (by Mancur Olson), and Niskanen’s work—were all written with the US in mind. They discuss pork-barrel politics, federal gridlock, and lobbying—all features of liberal democracies.

In India, the state is less porous and more opaque. Informal networks—caste, kinship, party loyalty—often play a bigger role than formal lobbying. Corruption isn’t always about money; it’s also about power and prestige. Students often struggle to see how public choice applies here.

The problem isn’t the theory. It’s the framing.

A Curriculum Problem

Most public policy and development programs emphasize tools like the policy cycle, stakeholder mapping, and theories of change. These are useful, but they rest on an assumption that actors are largely benevolent or at least neutral. Public choice challenges this by emphasizing the role of incentives and information asymmetries.

Even elite programs—like those at Harvard Kennedy School or LSE—only offer public choice as an elective. In India, it barely gets a mention in most public administration or development studies curricula. Even within economics departments, it’s treated as a niche.

This curricular absence means that students are unprepared to think critically about the political economy of reform. They may understand how to design a scheme—but not why it might be subverted in practice.

Other educators have faced similar resistance. Bryan Caplan, in The Myth of the Rational Voter (2007), talks about how people often vote based on emotion or identity rather than interest. This, he argues, makes democracy vulnerable to poor policy choices.

Peter Boettke and Edward Stringham have written about how public choice is unpopular in academia because it critiques the very institutions that academics depend on—the state, the university, the grant-making apparatus. Again, public choice proves its own point.

James Buchanan, in his memoirs, writes about being accused of ‘nihilism’ simply for asking why politicians behave the way they do. His response was simple: if we want better politics, we must first understand real politics.

Bringing It Back to the Classroom

So what can we do?

First, we need to localize public choice. Use Indian case studies. Talk about how school teachers lobby to avoid rural postings. How bureaucrats hoard unspent budgets in March. How voters trade support for short-term gains.

Second, we can teach it alongside other frameworks. Combine it with Ostrom’s institutionalism, or Acemoglu and Robinson’s work on inclusive vs. extractive institutions. This gives students a more balanced toolkit.

Third, we must de-ideologize it. Public choice is not about hating the state. It’s about designing institutions that work despite human fallibility. That is, after all, the original liberal insight.

Finally, let’s not shy away from the discomfort it causes. Learning should challenge our assumptions. If students feel uneasy, it means they’re thinking.

Public choice theory deserves more space in our classrooms—not because it has all the answers, but because it asks the right questions. In a world of increasing policy complexity and institutional fragility, we need frameworks that take human nature seriously. As trainers, our job is not to comfort our students with noble myths, but to equip them with tools to see the world as it is—and then to change it. Public choice, with all its provocation and precision, is one such tool.

Thankyou Sir, please share some case studies or papers in the Indian context.

What they need is a reader of case studies where Public Choice Theory improved policy outcomes. Having read about Public Choice Theory for decades, have my doubts that learning about the “theory” will be of any use to policy makers.