Dispatch #112: The Mission State- Why India excels in spectacle but fails in service?

This dispatch unpacks why the Indian state performs brilliantly during high-profile missions like the Kumbh Mela but struggles with everyday governance.

Humble Brag

Over the past six months, I’ve had the privilege of leading the capacity-building component under the NAKSHA programme — a national geospatial initiative spearheaded by the Department of Land Resources (DoLR), Ministry of Rural Development. As part of this effort, I’ve been supporting the design and implementation of the National Capacity Building Programme, which aims to equip officials from revenue and urban development departments and technical staff from 30 States/UTs with the necessary tools and training to integrate spatial thinking into land governance.

Working closely with the department’s leadership, I’ve helped steer this initiative from strategy to execution. Recently, the work under NAKSHA gained visibility when two parliamentary questions were raised in the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha regarding its capacity-building activities. I had the opportunity to assist the Ministry in drafting formal responses to both these questions — a small but meaningful contribution to a large and ambitious mission

Now, over to this week’s dispatch.

In January 2019, something extraordinary happened on the floodplains of the Ganga. A temporary megacity sprang up in Prayagraj to host the Kumbh Mela, a sacred Hindu gathering that attracted over 30 million pilgrims on a single day. Streets were spotless. Medical tents were staffed. Information centres buzzed with activity. Despite the logistical complexity, the event was heralded as a resounding success.

But just six years later, in 2025, tragedy struck. During another iteration of the Kumbh, a massive stampede claimed dozens of lives. Questions swirled about what went wrong. The same state machinery that had pulled off a logistical miracle had suddenly faltered. What changed?

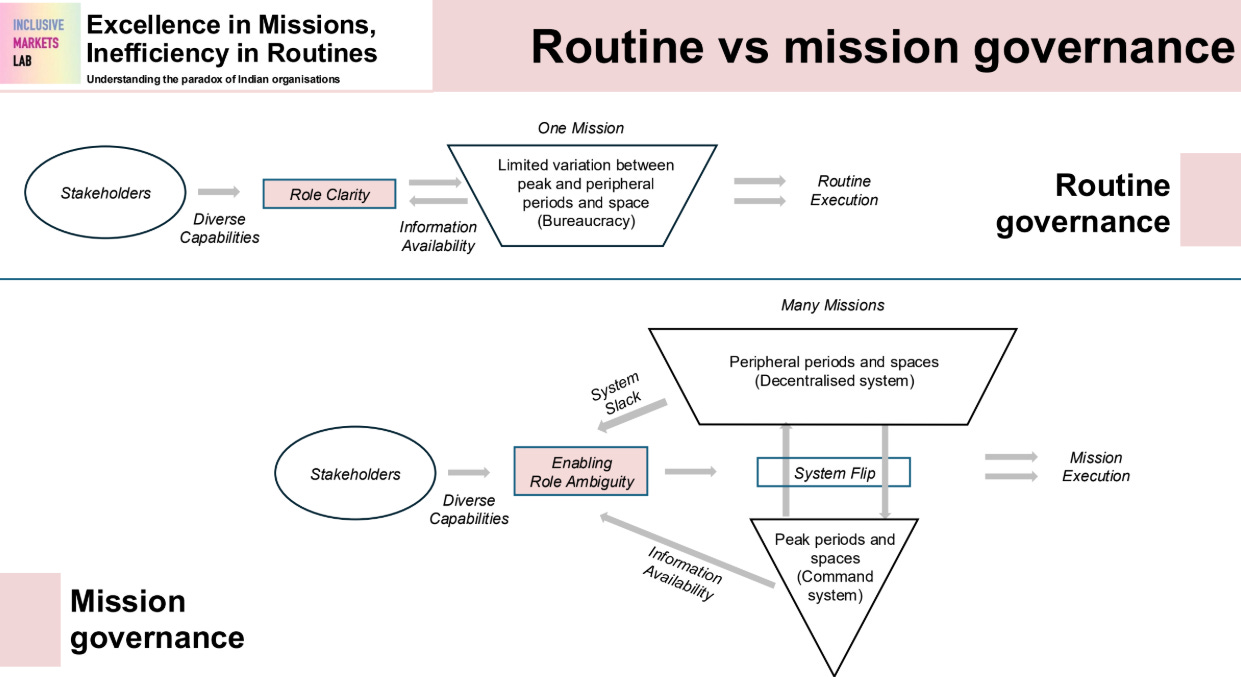

This contrast lies at the heart of a powerful insight from a study conducted by UCL Associate Professor Prateek Raj and other co-authors. Drawing on their fieldwork and institutional analysis, the authors offer a compelling diagnosis of India’s governance paradox: the Indian state performs brilliantly in mission mode but struggles with routine service delivery. The explanation hinges on what the authors describe the Dynamic Governance Model, a framework that explains why missions succeed and why they often fail to last.

The Indian State’s Dual Personality

To understand the authors’ key argument, we must begin with a simple observation: the Indian state has an uncanny ability to shine during “missions.” Think of India’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout, or the smooth conduct of national elections, or the organization of the Kumbh. These are high-stakes, time-bound, and visible efforts. They receive political attention, media coverage, and public scrutiny.

In contrast, the same state appears indifferent or dysfunctional in its everyday duties. Health centers remain understaffed. Public schools struggle with teacher absenteeism. Municipal systems fail to provide clean water or manage waste. These failures are not due to ignorance or apathy alone. They are symptoms of a deeper structural problem: the state is not built for routine governance, the way it is mobilized for missions.

The Anatomy of a Mission: Lessons from the 2019 Kumbh

In their study of the 2019 Kumbh Mela, the researchers observed that success did not come from rigid bureaucratic structures or a top-down command system. Rather, it came from what he calls a meta-organizational system, a loosely coordinated but purpose-aligned network of actors, ranging from government departments and consultants to volunteers and religious leaders. This system operated with remarkable cohesion, despite lacking a formal hierarchy.

What made this possible? The study identifies several key enablers.

First, there was role ambiguity. In most bureaucracies, people stick to their job descriptions. But during the Kumbh, engineers stepped in to manage logistics, consultants took on operational roles, and sanitation workers went beyond their assigned duties. This fluidity allowed the system to adapt in real time. People were driven not just by compliance, but by a shared sense of mission.

Second, the system was deliberately built in slack. There were spare buses, standby staff, and buffer budgets. While traditional administrative logic treats slack as waste, Raj shows that in dynamic systems, slack is essential. It provides room to absorb shocks, handle surges, and prevent breakdowns.

Third, there was an information infrastructure that supported rapid feedback. From loudspeakers and walkie-talkies to WhatsApp groups and drone surveillance, the system was in constant communication. This allowed for quick decisions, course corrections, and decentralized responsiveness.

Together, these features enabled what the authors call dynamic governance, a model where governance adapts to context, switches modes as needed, and relies on trust, improvisation, and coordination rather than strict rules.

The Collapse of the Model: Kumbh 2025

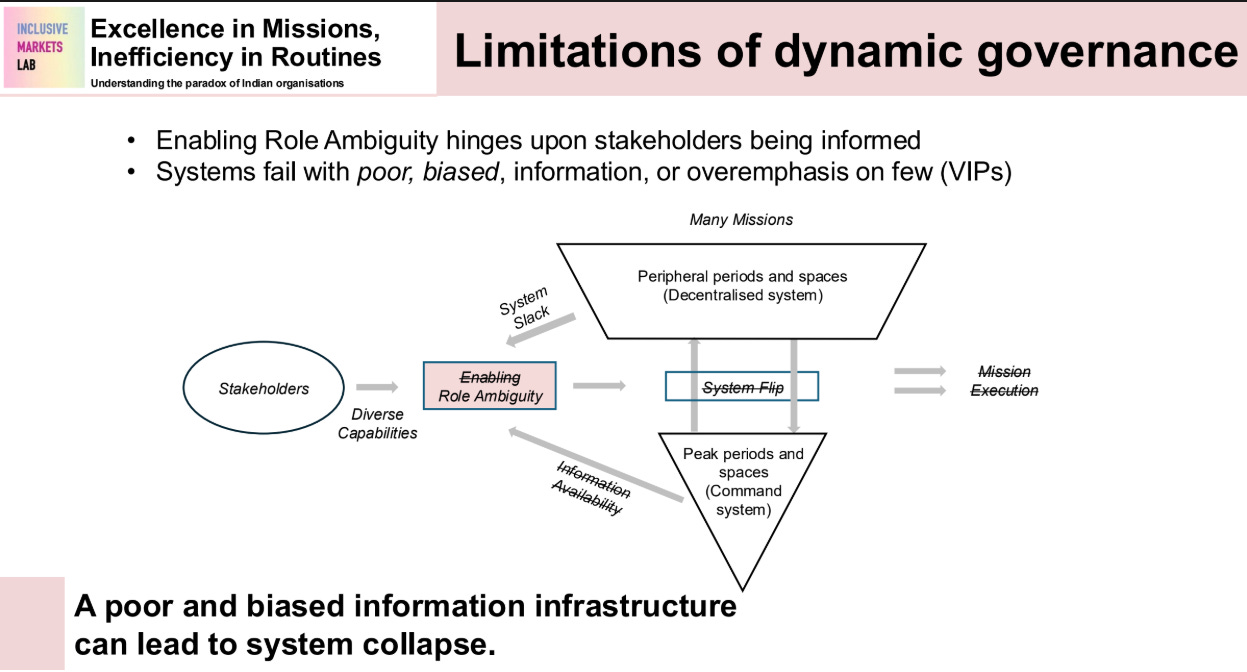

And yet, the same model that brought success in 2019 unraveled in 2025. A tragic stampede exposed just how fragile this dynamic system can be.

In 2025, many of the enablers were missing or weakened. Political incentives had shifted. Turf wars between departments re-emerged. Slack was reduced in the name of efficiency. The hybrid information infrastructure, once a backbone, became distorted, focused more on managing VIP visits than crowd safety.

Most crucially, the culture of collaboration had eroded. The ethos of improvisation and shared mission had given way to risk aversion and blame avoidance. Role ambiguity, once a source of strength, became a liability. No one took ownership. Everyone deferred to someone else.

The study’s conclusion is sobering: dynamic governance is not self-sustaining. It requires deliberate cultivation. Without the invisible scaffolding of trust, shared purpose, and coordination, the system collapses under stress.

Routine Governance and the Limits of Missions

These insights don’t just apply to mega-events like the Kumbh. They reveal something more fundamental about how the Indian state works, and why it often doesn’t.

In mission mode, the state activates a different gear. It becomes focused, resourceful, and adaptive. But in routine mode, governance reverts to its default: fragmented, hierarchical, under-resourced, and inflexible.

This is not a uniquely Indian problem. Many developing states suffer from what Lant Pritchett calls capability traps, where institutions look functional on paper but are hollow in practice. They chase ambitious goals without building the systems to deliver them. As a result, they “fail by trying too hard too soon.”

But India’s dual personality, its bursts of brilliance amid chronic dysfunction, is especially stark. This study shows that India doesn’t lack capacity. It lacks continuity.

Can We Institutionalize Dynamic Governance?

So, what can be done? Can the magic of mission-mode be extended into the everyday?

The study doesn’t offer silver bullets, but it points to a few possibilities:

Invest in institutional memory. Lessons from successful missions must be codified, shared, and embedded in routine systems.

Encourage flexible staffing and decentralized problem-solving. Routine governance must allow local officials the same latitude for improvisation that missions permit.

Build trust-based networks across departments. Collaboration cannot be episodic; it must be part of the culture.

Redesign performance metrics. Success must be defined not by compliance and paperwork, but by responsiveness and outcomes.

In essence, we must move from a static state to an adaptive one, capable of switching gears, sustaining energy, and responding to uncertainty.

The story of the Kumbh is not just about a festival. It’s a mirror reflecting the capabilities and contradictions of the Indian state. On its brightest days, India pulls off feats that rival any modern bureaucracy in scale, ambition, and execution. But those moments are fleeting. The deeper challenge lies in building a state that doesn't just rise for the extraordinary but quietly delivers on the ordinary.

The state that shines during a mega-event must also shine when no one is watching. It must ensure that the same dedication that brings a city to life for 30 million pilgrims is applied to keeping a village school functional, a health center stocked, or a garbage truck running on time. These may not make headlines, but they define the everyday experience of governance.

If missions are fireworks, brief, bright, and spectacular, routine governance must be like streetlights: consistent, invisible, and vital. The brilliance of a mission must not be the exception but the spark that builds institutions strong enough to outlive the campaign.

The dynamic governance model offers not just a critique of our present but a blueprint for our future. They urge us to ask: what would it take to design a state that learns, adapts, and endures, not only when the world is watching, but especially when it isn’t?

The real mission, then, is not another flagship scheme. It is to make governance so capable, so embedded, and so responsive that even the routine becomes remarkable.

Excellent analysis. You wrote an article sometime back about how China escaped Poverty. One of the points was Autotomy at local level having a common goal helped China during formative years of development. The only different is they sustained over a long period. What are your views?…thank you for writing.