Dispatch #13: Toilet- Ek safe katha

In this dispatch, we will see if there is a correlation between access to toilets and violent crimes against women in India

On August 14, at around 2:00 PM, Tara (name changed) from UP’s Lakhimpur Kheri’s Isanagar village stepped out to defecate. When she did not return back, after almost an hour since she left, her parents started to look for her in the fields. After hours of searching in and around the sugarcane fields, Tara’s father found her body and clothes.

She was raped and brutally murdered.

This case has many similarities with the Badaun case in 2014 where two sisters who went out to relieve themselves were found hanging from a mango tree. It was after this incident, when the policy makers started taking India’s sanitation policy seriously.

There is a substantial body of literature that claims that presence of toilets in rural households of India can reduce violent crimes against women. In this dispatch we will take a look at some of that literature.

Economist Ajit Karnik in this article argues in favor of the conjecture that violent crimes against women like rape is correlated to the lack of toilets in rural India. Using data from NSSO and NCRB, he claims that states where the toilet penetration is low are the same states where violence against women is the highest. Karnik accepts that there could be other factors also that may lead to increase in violence against women, such as law and order condition of the state, level of policing and the income of the state. In his blogpost, he calculated the estimated regression equation and found that after controlling all the above mentioned factors, it was the absence of toilets that emerged as a significant indicator that leads to increase in violence against women.

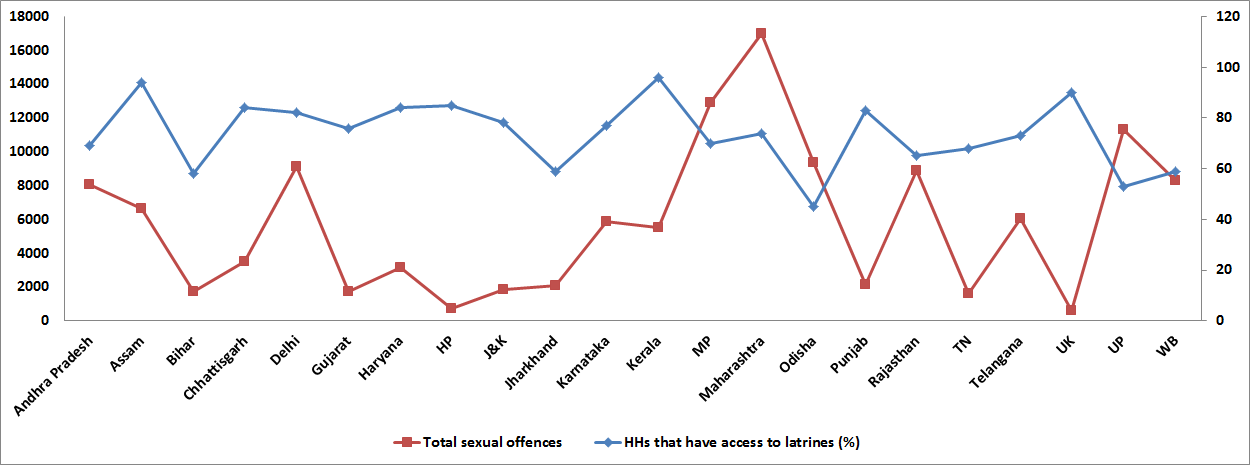

If we use data from the NSS 76th round on drinking water, sanitation, hygiene and housing condition in India and compare it with the total sexual offences data from the latest NCRB report, we will see that the correlation between the access to toilets/latrines and sexual offences against women do exist, vaguely. A lot of this correlation may be impacted due to under-reporting of sexual offences cases in some states.

The correlation is quite clear in states like UP,Rajasthan, Odisha, Maharashtra, MP etc.

Further reading to understand the relationship between toilet access and violent crimes against women or gender in general:

1) Access to toilets and public safety of women: Kanika Mahajan and Sheetal Sekhri in their article write, “The estimates from the first methodology we employ, show a reduction in sexual assaults and rapes in areas where more toilets were constructed. They show that a change in the percentage of households with toilets from 0 to a 100% would reduce sexual assaults by a significant 22%. We also find a 14% decline in rapes but this is measured imprecisely.

The empirical analysis shows a significantly positive effect of MLA alignment to BJP, on the pace of toilet construction, during 2015-16. The second methodology we use confirms the previous results for sexual assaults. The marginal affect is larger now with a 100-percentage point change in toilet access reducing sexual assaults by 70%. During 2014-2016, percentage of households having toilets increased by 22% in India. This implies a 15% reduction in sexual assaults against women due to construction of toilets during this period. We show that controlling for trends in other state characteristics do not affect the results. The results for rape are sensitive to our empirical specifications and do not pass our robustness tests. During this period there is also a significant change in reporting of rapes and laws related to rapes. The SBM was launched in 2014 after these changes. Hence, we are not able to infer any statistically meaningful effects on rapes from our data possibly due to these other changes.”

2) Lack of Toilets and Violence against Indian Women: Empirical Evidence and Policy Implications: Raji Srinivasan from University of Texas at Austin uses ‘social disorganization theory’ to explain how lack of toilets in Indian households lead to non-partner sexual violence against women.

He writes, “In emerging economies such, as in India, the social composition of communities is changing rapidly because of substantial internal (i.e. intra-country) migration including from rural areas to urban areas, from small cities to big cities, and even from one area of the country to another area where economic prospects may be better. Thus, we anticipate that the level of social disorganization in communities in both urban and rural areas in India will be high, decreasing social capital decreasing and social controls, and increasing the risk of non-family violence, more generally, but especially in vulnerable populations, such as children and women. Thus, we propose that when women who live in Indian households without toilet facilities, are forced to go outside their homes into the community to relieve themselves, they are being exposed to socially disorganized communities and may be subject to violence from non family males in the community, increasing the incidence of non-family violence against them. What might social disorganization theory say about the relative incidence of non-family violence against urban (vs. rural) Indian women in households without toilet facilities? As noted above, according to social disorganization theory, normative consensus and social controls are undermined by increasing population size, density and heterogeneity characteristics of urban communities. As the population density of the community increases, variation in the population characteristics increases, resulting in poor communication among groups of the community’s residents. Thus, it may be difficult for crowded, and diverse urban communities (such as those in urban India) to regulate themselves because of decreased social capital and social controls.”

3) No toilet, no bride- Toilet ownership and marriage prospects of men in India: Britta Augsburg and Paul Andres find that the ownership of toilets is dependent on the financial status of the household. Hence richer households with higher levels of education are more likely to own toilets.

They write,"The determinants of toilet ownership and acquisition that our findings reveal are for the most part, in line with expectations. We find for example that richer households, households with higher education, and households from higher castes are more likely to own a toilet. Similarly, households with savings and greater credit access are also more likely to make sanitation investments. Interestingly however, a further finding reflects a shift towards greater inclusion over time along these margins.”

They further found that “households with boys of marriageable age are, on average, 10 percentage points more likely to invest in a toilet than households with girls of marriageable age – which can be interpreted as a clear signal that toilet investment are believed to improve outcomes in the marriage market.”

4) The Bargaining Power of Missing Women- Evidence from a Sanitation Campaign in India: In this brilliant paper, Yale University’s Yaniv Stopnitzky studied ‘No toilet, no bride’ programme in Haryana and found that men tend to increase investments in toilets if the groom’s sanitation preferences are strong. It was also found that the households that have men in the marriageable age were more likely to invest in toilets.

Yaniv concludes, “Because the program encouraged girls’ families to demand from boys’ families a latrine prior to marriage, it generated disproportionate pressure to construct a latrine specifically among those households whose boys were of marriageable age and seeking a bride. I demonstrate that marriageable boy households were indeed affected disproportionately by the program, and I estimate the “No Toilet, No Bride” treatment effect to have increased latrine ownership by 15% over the baseline mean of Haryana households with marriageable boys in 2004. In addition, estimates of latrine adoption in Haryana posttreatment are four times larger in marriage markets characterized by a scarcity of women as compared to marriage markets with more women than men.”

5) Gender, electoral competition, and sanitation in India: Colorado University’s YuJung Lee explores the role of female Indian politicians and improved sanitation facilities.

She writes, “The results suggest that a one-percent increase in the share of female state legislators results in a 0.37 percentage-point increase in the share of rural households with high-quality latrines in districts with close elections. This suggests that female politicians improve sanitation in ways that matter for women’s well-being, even after controlling for the role of electoral competition.

This is not true for low-quality latrines and in fact I find that districts with more female politicians are less likely to have low-quality latrines. Instead, greater access to low-quality latrines is associated with having more competitive elections and having more politicians from the national ruling party in state legislatures. In other words, districts that have politicians elected from more competitive elections, on average, are more likely to have low-quality latrines. This suggests that with more competitive elections in general, politicians increase the visibility of their performance by providing low-quality latrines because it is an easier way to signal their performance to voters and gain electoral support. Ruling party members also have an incentive to focus on policies that are more easily observed by voters to continue their power.”