Dispatch #14: Weekend Linkfest

Here is a curated list of some good articles from the world of policy, politics and development

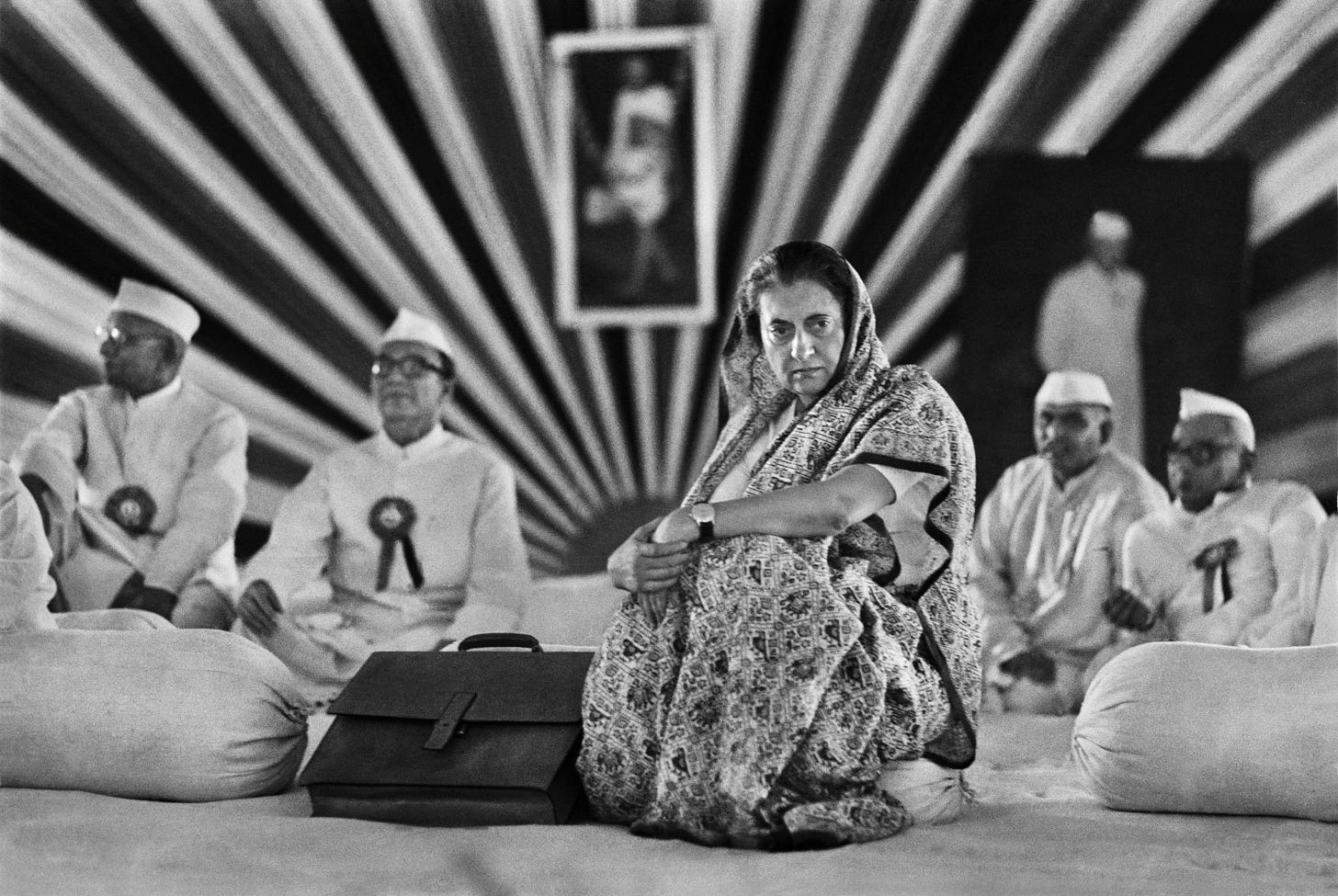

1) On economic growth, there is much we can learn from our past and from Pakistan: Economist Amartya Lahiri compares the growth trajectory of Indian and Pakistan. He writes, “Pakistan’s slowdown began in the 1980s during the military regime of Zia-u-Haq. Zia enabled and institutionalised Islamic nationalism in Pakistan. This period coincided with the reforms in India. As a result, the income gap between the countries began narrowing sharply. Nevertheless, it wasn’t till as recently as 2010 that India’s per capita GDP finally overtook Pakistan. Put differently, starting in 1985, it took 25 years of faster growth for India to finally undo the damage inflicted by the inward-looking, anti-industry, anti-trade and anti-foreign capital economic regime that was erected by the Indira Gandhi government.

From the specific perspective of India, the trends reveal three key facts. First, India did reasonably well during the Nehru era. This is at odds with the increasingly strident recent criticisms of the Nehru years. Second, the biggest damage to the Indian economy was done during the Indira Gandhi years, which saw negative growth over two decades. Bizarrely, her administration appears to have escaped the virulent criticisms that have been directed at the Nehru years. Third, the Rajiv Gandhi government deserves way more credit for ushering in the first growth turnaround of the economy. In some senses, the post-1991 reforms were a consolidation of a process that began under the Rajiv Gandhi government.”

2) Regional parties fail to cross the final poll hurdle: BJP seems to be invincible, yet it is facing challenges by the regional parties in state elections. Despite acting as challenger, the regional parties are still falling short of gaining majority in the states. Political scientist Rahul Verma explains this paradox. He argues that there are 3 factors that can explain this paradox- generational transition from the old order to the new order; failure of regional parties to expand their support bases and recent policies by the BJP that have eroded the finance and the support base of the regional parties.

Rahul adds, “State-level parties often had controlling stakes in ruling coalitions and influenced policymaking. And it is likely that in the BJP-dominant system, the bargaining power of these parties will be on the wane. However, given the civilisational diversity of India, political entrepreneurs will continue to populate the competitive landscape. The assembly elections in five states where regional outfits are an important force — Assam, Kerala, Puducherry, Tamil Nadu, and West Bengal — next year will determine the nature of Indian federalism in the years to come.”

3) It’s dishonest to deny the realities of Lalu’s misrule and lawlessness. Here’s why: In the run up to Bihar elections there was a raging debate whether Lalu’s 15 year rule in Bihar can be regarded as ‘jungle raj’. Anand Vardhan writes that to ignore the lawlessness and anarchy during those 15 years under the garb of the politics of social justice will be a grave injustice to those who have lived through that tumultuous period. He writes, “The naïve acceptance of Lalu’s false victimhood rhetoric, and turning a blind eye to his subversion of empowerment of backward communities, amounts to a gross case of misreading of contemporary politics. It also reveals the failure to grasp the dynamics of a strand of social justice politics in the Hindi heartland which has often abandoned its core cause at the altar of dynastic politics. In some ways, there is a different strand to it, and it’s represented by the stream of social justice politics represented by non-dynastic Lohiaties like Nitish.

The misgovernance and lawlessness of the Lalu regime, captured with the evocative phrase of “jungle raj”, was a lived reality for millions. The efforts to deny memory of that dreadful chapter of the past, and the comparative perceptions of the present, are historically dangerous exercises and journalistically dishonest exercises.”

4) Asaduddin Owaisi’s rise is just the opportunity Hindutva politics is waiting for: Is the rise of Asaduddin Owaisi’s AIMIM a reaction to the majoritarian politics of the BJP? Yogendra Yadav believes so. Yet he is apprehensive. In this provocative piece he writes, “This rise of Muslim exclusive politics at the national stage could well be the perfect partner that Hindu majoritarian politics has been waiting for. This would mean absence of any political incentives to bridge the Hindu-Muslim divide on either side. By voting the BJP to power again, the Hindu majority has already rejected secular politics. If the minorities, too, find it useless, that is the end of the idea of secular India inscribed into our Constitution. Secular politics must respond to this danger by transforming itself. It does not have much time.”

5) Reforms without growth: P Chidambaram writes, “In my view, Mr Modi is a cautious leader with a strong bias towards crony capitalism. He supports incipient monopolies. If he wants to undertake genuine, bold reforms — which he can do given his absolute majority in the Lok Sabha, something that neither Narasimha Rao nor Dr Manmohan Singh enjoyed — a list can be put together. The ultimate test of a reform is whether the reform adds to or accelerates the growth rate of the GDP. By that unquestionable standard, the ‘boom years’ under

Dr Manmohan Singh make Dr Singh the reformer par excellence. Let Mr Modi deliver growth before he can aspire to a place among the pantheon of economic reformers.”

6) Reforms for what — growth or glory? In another piece, as a reply to Arvind Panagariya’s assessment of Modi as a reformer, Chidambaram writes, “Here is a severely limited list of reforms during 2004-2014:

1. VAT, 2. MGNREGA, 3. Aadhaar, 4. Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT), 5. ‘No frills’ or ‘Zero Balance’ bank account, 6. Consolidation of Regional Rural Banks, 7. Right to Education Act, 8. National Rural Health Mission; ASHA, 9. National Urban Renewal Mission, 10. National Horticulture Mission, 11. Weather-based crop insurance, 12. Model law on APMC, 13. National Skills Development Mission & Corporation,14. CENVAT on all goods and services, 15. Long Term Capital Gains on securities abolished, 16. Introduction of STT, 17. FDI in retail, 18. Private participation in coal mining, 19. Eliminating subsidies for Petrol & Diesel, 20. Gender Budget, 21. Demutualisation of stock exchanges, 22. PFRDA Act, 23. Companies Act, 24. National Food Security Act, 25. Right to Fair Compensation(LARR) Act, 26. Forest Rights Act.

“I did reforms” is for self-glorification. “My reforms brought growth” is for the people and for posterity. You be the judge."

7) Devotion and economic progress- How does religious intensity affect development? This AEA blog talks about the latest study done by Bocconi University economist Mara Squicciarini, who explains how religious intensity can impede scientific and industrial development. Giving the example of France during the second industrial revolution,the blog says, “The rail industry expanded rapidly and saw the adoption of new sources of power, such as the diesel engine and electric locomotives. Electrification spurred a new era of manufacturing and mass production. The industrial machineries became more complex and sophisticated and they increasingly relied on mechanical skills. Primary schools became an essential component for the formation of this skilled workforce. But the Catholic Church was resistant to change. It promoted a conservative, antiscientific program that emphasized religious education over the technical curriculum being introduced in secular schools.This tension was particularly acute in France, which experienced spectacular scientific and economic development.”

8) Roads of fire: labor exits, crop-burning and the environmental costs of structural transformation: In this insightful blog, Stanford University’s Hemant Pullabhotla, argues that the transition of Indian economy from agrarian to industrial, has resulted in labor exiting agriculture. This has resulted in farmers adopting burning of stuble in North India since it is less labor intensive and has low cost. Hemant writes, “We focus on one specific environmental consequence of structural transformation: the increased use of fire as a labor-saving but polluting technology by farmers in India. Farmers use fire as a low-cost means of clearing crop-residue left after harvest, ease harvesting of sugarcane, and clear undergrowth on fallow lands in shifting agriculture. These agricultural fires are a growing environmental and public health concern in India, contributing to as much as half of the particulate pollution in many parts of the country during the winter months. We present the first evidence that agricultural labor exits compel farmers to use a labor-saving but polluting technology -- fire -- resulting in increased particulate matter.

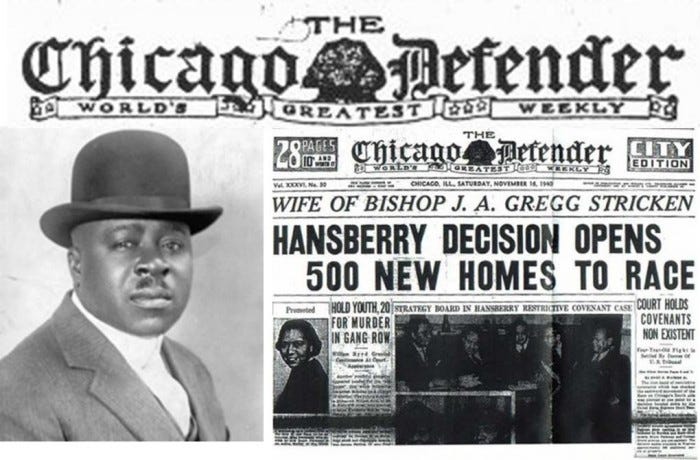

9) Upper-caste Domination in India’s Mainstream Media and Its Extension in Digital Media: In this searing piece, Dilip Mandal talks about the diversity in newsrooms. The best part of the article is the analysis of upper-cast hegemony and under-representation of people from the SC and ST community. Mandal asks when will India have her own Chicago Defender while being optimistic that internet has given a space to Bahujan media even though their voice is missing in the mainstream media. He writes, “Upper-caste domination in Indian media spaces continues even after the advent of digital and social media. The SCs, STs, and OBCs have launched a number of digital media platforms, but they are just trying to fill the gap created by the upper-caste-dominated media. Dalit–Bahujan media is proliferating, but these platforms are still at the margins of the various discourses dominating the Indian society. The saddest part is that in India, we do not have anything resembling the Chicago Defender in the print, television or digital space. After almost one-and-a-half decades of India’s tryst with digital and social media, we are now in a position to say—with the empirical data to prove it—that the upper-caste domination in legacy media has reproduced itself in digital media. The hope of a democratic digital media appears to be a myth.”