Dispatch #24: Weekend Linkfest

Here is a curated list of a few good articles from the world of policy, politics and development.

1) Key numbers, ideas in the Economic Survey:

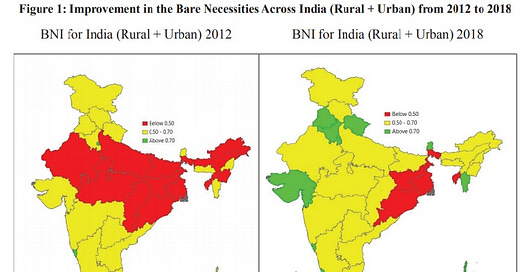

The Economic Survey 2020-21 has constructed a Bare Necessities Index, a composite measure of access to bare necessities for households in rural and urban India, for the years 2012 and 2018. The index is based on 26 comparable indicators on five dimensions – water, sanitation, housing, micro-environment, and other facilities. Between 2012 and 2018, access to the bare necessities has improved across states and the disparity between the states has reduced. A look at the 2018 figures shows that people in southern and western states are generally better placed in terms of having access to the bare necessities.

It was found that compared to 2012, access to “the bare necessities” has improved across all States in the country in 2018. The improvements are widespread as they span each of the five dimensions viz., access to water, housing, sanitation, micro-environment and other facilities. Inter-State disparities in the access to “the bare necessities” have declined in 2018 compared to 2012 across rural and urban areas. This is because the States where the level of access to “the bare necessities” was low in 2012 have gained relatively more between 2012 and 2018. Access to “the bare necessities” has improved disproportionately more for the poorest households when compared to the richest households across rural and urban areas. The improvement in equity is particularly noteworthy because while the rich can seek private alternatives, lobby for better services, or if need be, move to areas where public goods are better provided for, the poor rarely have such choices. It was also found that the improved access to “the bare necessities” has led to improvements in health indicators and in education indicators. However, while improvements in access to bare necessities are evident, the disparities in access to bare necessities continues to exist between rural-urban, among income groups and also across States. Government schemes, such as the Jal Jeevan Mission, SBM-G, PMAY-G, may design appropriate strategy to address these gaps to enable India achieve the SDG goals of reducing poverty, improving access to drinking water, sanitation and housing by 2030.

2) Fixing software bugs in India’s economy:

Arvind Subramanian and Josh Felman write, “One possibility is that the “hardware" of reform measures has not been accompanied by sufficient “software". What is the software of economic reforms? Traversing the sequence from planning to implementation sound policies require accurate data, fair decisions, statecraft to win support, policy consistency over time, and rule of law in implementation. This software affects the impact of reforms because it engenders (or damages) credibility, that is, the trust of investors, citizens and the states. And trust is critical for convincing firms to invest and states to implement centrally-sponsored schemes.”

3) State of the Indian economy- Diagnosis and recommendations:

Ashok Kotwal has summarized the Subramanian and Felman paper in this article. He writes, “The authors believe that most of these policy initiatives were wisely chosen (good ‘hardware’) and yet were only partially successful in the way they functioned due to the fact that the government did not succeed in securing a buy-in from all concerned parties. This, in turn, was due to the lack of political skills in persuasion and public communication with a large number of those who had a stake in the policy initiative at hand (bad software). Further, this was perhaps attributable to the loss of government’s credibility and trust. Questionable government data and the unethical ex-post Vodafone judgment were the kinds of developments that potentially caused an erosion of public trust in the government. The authors’ prescription to correct this software bug are: accurate data, fair decisions, Statecraft to win support for the measures, policy consistency over time, and rule of law in implementation.”

Source: CNN

4) The real darkness on horizon is the turn Indian democracy is taking:

Pratap Bhanu Mehta, in the searing piece writes, “The language of order, and the pieties of the flag in which it is wrapped by the state and the media, is not about order at all. The language of order is partisan to the hilt. It is weaponised to crush dissent. It is used to empower repression. It is used to desecrate the spirit of constitutional values. But it gives even the supposedly most liberal amongst us the perfect pretext to rally behind the government once again. It gives a pretext to appease our consciences that we can ignore the systematic repression of civil liberties, the runaway crony capitalism, and the frightening communalism of the state, the criminalising of dissent, the desecration of federalism and the collapse of institutions. It allows us to ignore the fact that the most influential and powerful sections of society from legal professionals to academics and media, from owners of capital to bureaucracy, have connived in creating the conditions of disorder, by closing off legitimate channels of democratic deliberation, and actively supporting authoritarianism and communalism. The government may have won the battle of perception by playing on a disingenuous language of order. But the open wounds it has created will fester and create long-term problems. The cycles of repression, protest and more repression will continue. The real desecration did not happen at the Red Fort. It happened when we created a country where jokes, acts of love, and democratic articulation are all deemed anti-national.”

5) The roots of the BJP’s unilateralism:

Rahul Verma writes, “The Modi-Shah doctrine, for right or wrong reasons, is rooted in the belief that opposition to their regime is not based on principled positions. The vehement opposition the party faced inside the Parliament and on the streets between 2014 and 2016 — remember the protests against the amendment to the land acquisition legislation, the award wapsi marches, electoral losses in Delhi and Bihar, the suit-bootki sarkar jibe, among others — led them to conclude that despite the party’s historic win, there is an obstructionist cabal that thinks that the BJP has no right to govern India. The BJP believes that there is a network of academics, activists, journalists and few Opposition leaders (the Khan Market gang in its lingo) that keeps scheming to delegitimise the Modi government in the public eye. It is because of this intractable nature of the Opposition, the party suspects, that the protests against government policies are not restricted to a specific clause or point, but often seek a complete reversal of the government’s position or a reversion to the status quo. And, therefore, in order to neutralise this cabal, the BJP is also pushed to assume a maximalist position to mirror and counter the maximalist position of the Opposition. In its calculation, this ensures that even a mid-point reached through negotiations changes the equilibrium in the BJP’s favour.”

6) Elections, Populism and the ‘Supreme Leader’- The Rise of Authoritarian Democracies:

Manjari Katju writes, “To answer the questions about the rise and continuation of populist authoritarian democracies, one has to remember that the institutional structure of a democracy is such that there is always space for the rise of a strong political executive. A popularly elected leader can lean on people’s backing to personalise state power. This authoritarian tendency is built into the institutional apparatus of democracy and has been a feature of both parliamentary and presidential systems. Popularity and state power make a formidable combination — it equips one with tremendous power and the ability to rule with an iron hand. This concentration of power can range from mild to heavy, and is morally justified as an expression of ‘people’s will’.

Paradoxically, ‘people’s will’ becomes a weapon to subvert people’s choices and freedoms. Criticisms are warded off as ‘attacks’ on people’s will or subversion of the people’s choice. The leader can take the most unpopular of decisions or those that completely purge dissent. The leader often builds a small group, a coterie of trusted individuals that becomes a centre of all important decisions. This is institutionally permissible, formally as a ‘cabinet’ or informally in a variety of advisory groups. Such a caucus becomes a site of power and the executive at the helm of affairs is often found to ignore legislative opinions or heavily influence them. In any case, since the legislatures are composed of ruling party majorities, there is no problem in carrying out the whims of the executive leader.”

Source: Mint

7) How India has become an unequal republic?

On inequality, Jaffrelot and Kalaiyarasan write, “The rising inequality is termed as “billionaire raj" by Lucas Chancel and Thomas Piketty. They show the sharp rise of income, particularly of the top 1%. They present an overall U-shaped curve of inequality in the last 70 years—declining inequality from 1950s to 1980s followed by a sharp rise thereafter. Also, they contest the hypothesis about the rise of a middle class in India. In their analysis, it is the top 10% who benefited the most as compared to the middle 40%.”