Dispatch #29: Weekend Linkfest

Here is a curated list of a few good articles from the world of policy, politics and development.

1) Rising petrol prices, shrinking savings don't matter – India’s middle class is mesmerised by Modi:

Shoiab Danyal writes, “This silence in the face of economic hurt underlines the strong support for the BJP, Modi and eventually Hindutva from India’s middle classes. Most data points to the fact that in the middle class, the BJP has a more stable vote bank than almost any other party in India. In 2019, one of the largest post-poll surveys done across India found 38% among middle-class respondents and 44% among the upper-middle class voted BJP which was, by far the most popular party in that category. Since the BJP appeals only to Hindus amongst the middle class, an astounding 61% of Hindu upper-caste voters surveyed picked the BJP in 2019. This points to a deep ideological relationship – which clearly has the potential to withstand economic shocks, with the Indian middle class, at least for the time being, ready to vote against their own economic interests.

What works additionally in favour of the BJP is the lack of any other party which attracts middle class support. The Congress, while traditionally a party that attracted middle class support, has seen its support collapse post 2014, with the BJP significantly increasing its standing amongst them between 2014 and 2019.”

2) Seize the moment:

Asim Ali asks 2 questions, about the opposition parties, in his article:

a) ‘Can these parties use these protests alone to inflict electoral damage on the BJP?’

b) ‘Can these parties use the energy of these protests to rebuild their political capital?’

He answers the first question by writing, “The first question is unclear because there have been other farmer agitations in the last few years and farm distress has long been prophesied as the Achilles’ heel of the BJP’s dominance. Yet, the BJP substantially enhanced its vote share among both farmers and rural areas in 2019 compared to 2014. In fact, as a proportion, more farmers voted for the BJP than non-farmers. Only in the 2017 elections in Gujarat did we see concrete evidence of farmer distress playing a key role in hurting the BJP. In some other states, farm distress has been misattributed as a major reason for the BJP’s reverses. In rural Haryana, for instance, it was the Jat backlash over political marginalization that dragged the BJP down, not wider rural distress. In Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh, as the political scientist, Neelanjan Sircar, demonstrated, the BJP’s victory strike rate dwindled as much in urban seats as in rural seats, indicating a wider disenchantment.”

Asim further writes, “A key challenge to this ideological repositioning is that Opposition parties must integrate their diagnosis of the farmer crisis with their larger thesis on economic precarity, joblessness, and development. This is because farmers are equally concerned with these issues as their urban counterparts. In fact, some of the largest agitations of peasant castes in recent years — the Patidars in Gujarat, the Marathas in Maharashtra and the Jats in Haryana — have been on the issue of jobs. For instance, Rahul Gandhi must also explain how crony capitalism of the BJP threatens jobs and development, and what is the alternative vision of the Congress in addressing those challenges.”

3) More young urban Indian men appear to be studying longer, not looking for jobs:

Using NSSO and PLFS data, economists Vidya Mahambare, Sowmya Dhanraj and Sankalp Sharma (VSS) have written a 4 part series on trends in employment, labour workforce, female labour force participation rate and youth education in India.

In their first article, VSS write, “Twenty-two per cent of young men were not looking for work in 2017-18, up from 14 per cent in 2004-05. In both the years, a vast majority of them, over 87 per cent, were in education. It would, therefore, prima facie appear that more young men are staying longer in education now. Surprisingly, however, a higher proportion of men in the laggard states with lower average educational levels were not looking for work and enrolled in education. For example, Jharkhand and Bihar have a disproportionately higher share of young men – 33 per cent and 43 per cent, respectively, who were out of the labour force. In contrast, in Gujarat and Tamil Nadu, only 15 per cent of young men were not looking for work.

What does this statistic mean? First, it appears that it takes longer to complete degree-level education in states such as Jharkhand and Bihar, given the poor functioning of the local education system. For example, 15 per cent of young men in the age group of 20-29 in Bihar report having completed higher secondary, are currently attending education, presumably to complete their degree, and are not looking for work. In contrast, in prosperous states such as Tamil Nadu, the same proportion is only about 5 per cent. Second, young men may continue to stay enrolled in educational institutions or in training institutes to prepare themselves for the public sector competitive exams, hoping for a lucrative government job. Third, they may be disillusioned with poor local job opportunities, and stay enrolled in some form of education until they can migrate to other states.”

About the impact of late entry in the job market, VSS write, “A significant delay in joining the labour market implies a later than usual start to their working life. This can have potentially adverse consequences for lifetime earnings and the kind of jobs they hold over the course of their working life. Moreover, a higher proportion of young adults not looking for work increases the dependency burden on the working population.”

4) In ‘progressive’ Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, only 1 in 5 young urban women in paid work:

In their second article, VSS write about how the educational gap between men and women is narrowing in India, but the gender gap in employment has increased, even in richer states.

They write, “While we do not know about the quality of education, the gender gap in education seems to be narrowing over the years. In contrast, the striking difference is in the share of the employed men and women. Nearly 64 per cent young men, but only 16 per cent of young women are employed. Even in the southern states of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, which are progressive in terms of gender equality, only 20-22 per cent young urban women were in paid work. The reason is well-known – majority of young women, 60 per cent, staying at home to take care of household duties and children. The pandemic has further increased, notwithstanding the help rendered by men, the burden of household and care work on women. Schools and daycare centres have been shut and with all the family members staying at home, the time taken for tasks such as cooking and other household chores has increased in the absence of usual domestic workers.

Not surprisingly, the highest proportion of young women who report being devoted to household work full time are in urban Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. But even a prosperous state such as Gujarat, in its urban centres, has over 70 per cent of women in this category. In contrast, urban Kerala has less than 40 per cent of young women in full-time domestic duty and the highest – a little over 20 per cent into education.”

5) Manufacturing or high-tech? This is what India’s most prosperous states focus on:

In the third dispatch VSS talk about how 4 prosperous states (Maharashtra, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka) charted different growth and employment trajectory due to different sectors acting as growth engines.

They write, “It is interesting that these states have reached their current similar prosperity levels by following different development models. While in all four states agriculture now accounts for only 10-15 per cent of the economy, the rest of their economic structure differs markedly in terms of the importance of manufacturing and high-tech services.

In 2018-19, the highest gross value added (GVA) comes from the manufacturing sector in Gujarat (38 per cent of total value added), while the financial, real estate and professional services account for a similar share in Karnataka. In contrast, the share of manufacturing is only about 18 per cent in Karnataka. Tamil Nadu has the most balanced growth model with manufacturing and high-tech services each contributing nearly one-fourth of the GVA. Maharashtra’s growth is tilted towards high-tech services, although not to the same extent as in Karnataka.”

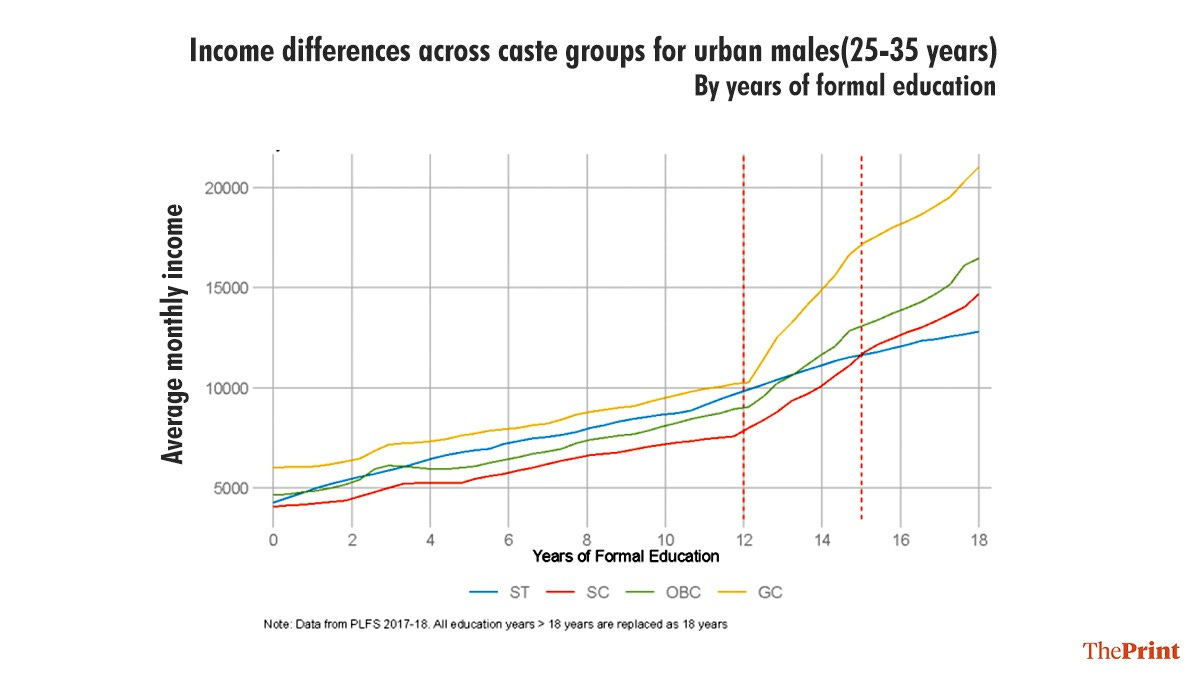

6) Education levels of SC, ST, OBC rising. A new study looks at caste gap in jobs, income too:

In their final dispatch VSS argue that in India, among the social groups, the educational levels have risen across all- General Category, OBC, SC and ST. The affirmative action in higher education and public jobs have also led to increase in job levels and inclusiveness across all social groups. However the biggest catch up in terms of rise in income levels have been to the OBCs.

They write, “While the income level of a young person belonging to GC continues to remain higher than other caste groups at all levels of education, the income differences become larger among young adults with tertiary education (graduate or post-graduate levels).

In sum, we find that while progress has been made by all, young men from OBCs have seen a larger catch-up. The returns to higher education in terms of wage disparities in different caste groups however, remain significant. Closing the caste gap in education, jobs and incomes of young men continues to be a work in progress in urban areas.”

7) Brand India:

Historian Ravinder Kaur, in her insightful article, explains how the economic liberalization and right-wing majoritarianism in India have complemented each other. She writes, “It’s hardly a surprise, then, that India’s march to become the ‘factory of the world’ – a global space of production that contains natural resources, cheap skilled labour, technology as well as a vast consumer market – is an essential partner with pro-capital Hindu majoritarianism. At the heart of this alliance is the pursuit of economic growth, a project that calls for discipline and obedience to the strongman leader who ‘means business’ in more ways than one. This strongman appeal of Modi as a hyper-masculine Hindu leader is how he first attracted and won support from captains of industry. Capital has long favoured authoritarian leaders who can capture resources and put them at the disposal of investors, and also produce good news campaigns to celebrate the ‘growth story’ of the nation.”

8) BJP’s hegemony and party structure spark concerns. But its power is fragile:

Neelanjan Sircar’s article on BJP’s hegemony is a good primer to understand the ongoing farmer protests and stifling of dissent calling out every criticism as ‘foreign conspiracy’.

Sircar writes, “Fundamentally, when a party is hegemonic, the chief aim of policy is to bolster its own organisation and entrench it in society. The logic that stifles criticism within a party must then be extended to the population as a whole. From this perspective, the characterisation of what is national interest or anti-national or what is an assertion of Hindu identity or anti-Hindu is not a matter of discernible ideology. It is curated by the political party in power and generates narratives that strengthens the party vis-à-vis its opponents. While there may be legitimate, even widely held, criticisms of the BJP government’s economic or agricultural policy, citizens are likely to withhold public criticism or face intimidation from government supporters when they do so. The problem is that when criticisms from the ground cannot easily reach those in power, then the government cannot efficiently correct flaws in its policies — as it is surrounded by yes men.”