Dispatch #3: With COVID-19 cases rising, what can India learn from South Korea & Vietnam?

In this dispatch, we will be talking about CFR due to COVID-19 in India; South Korea's and Vietnam's strategy to control the pandemic; loss of livelihoods due to lockdown among other things.

Even as the number of confirmed cases and deaths due to COVID-19 is rising with each passing day, according to an analysis done by Factly, the Case Fatality Ratio (CFR) or the number of deaths due to COVID-19 divide by the number of positive cases shows a decreasing trend in India.

Karnataka registered the first-ever COVI-19 related death in March. After that, the number of fatalities has increased across the country with states like Maharashtra, Delhi, Gujarat and Tamil Nadu recording the maximum number of deaths.

The average number of COVID-19 deaths in India were being reported in double digits in the beginning of April 2020. The numbers have gradually increased over the remainder of the month, with daily average of deaths crossing 100 during the first week of May. By the end of May 2020, the number of reported daily deaths were just below 200.

The month of June 2020 saw a considerable increase in the number of reported daily deaths. The one-day spike on 17 June, as indicated earlier, had an influence on the average. Despite this anomaly, the number of deaths being reported was in the 300-400 range for the rest of June.

However, since the beginning of July, a higher number of daily deaths are being reported, as the number of positive cases is also rising. As of 8 AM on 05 July 2020, a total of 613 deaths were reported (not average) in the previous 24 hours. The 7-day moving average has also increased to around 453.

-Factly

While the number of deaths is increasing, the death rates or the Case Fatality Ratio (CFR), described earlier, has declined. This dip in the death rates can be attributed to the increase in the number of confirmed cases compared to the deaths. Since the denominator is increasing fast, the ration, overall, is decreasing.

During the month of June 2020, the fatality rates have increased from 2.8% to a peak of around 3.3% (on 17 June when 2000 + deaths were reported). However, it has shown a subsequent decreasing trend with the CFR going back to around 2.8% by 05 July 2020.

-Factly

While the CFR for India is 2.8%, it varies from state to state. Gujarat (5.45%), Maharashtra (4.33%), Madhya Pradesh (4.09%), West Bengal (3.47%), Delhi (3.09%) and Uttar Pradesh (2.91%) have CFR higher than the national average. But there are chances that these COVID-19 related deaths in India are under-reported as the India Spend report claims.

How did South Korea and Vietnam flatten the curve?

South Korea has been able to flatten the epidemic curve successfully without implementing strict lockdown orders like what India did. The secret to its success lies in the fact that its health system was ready to control the epidemic just when the confirmed cases started to rise in February 2020. South Korea’s swift response has also to do with its botched up response to the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2015. After this experience, the government has reformed the health system to be prepared for any other major outbreak. The number of beds per thousand population in South Korea is much higher than in several high-income countries. South Korea has 12.3 hospital beds per 1000 population. This is far more than the number of hospital beds in Germany, US, UK or China. This acted in her favour when the number of cases started to peak. ICT played a very important role in South Korea’s fight against COVID-19. The Cellular Broadcasting Service (CBS) transmitted emergency alert messages to the subscribers when the outbreak happened. In addition to this several advanced ICT apps were developed to dispense important information related to the pandemic to the citizens, contact tracing and steps to be taken during self-quarantine.

The epidemic preparedness and response framework in South Korea comprised of these essential steps, which its government aggressively pursued:

1) Detection

2) Containment

3) Treatment

Detection: As soon as few cases were detected in South Korea in January, the government sprang into action. The Korean Center for Disease Control was already receiving viral specimens from China to develop diagnostic tools. With cases rising in February, the government roped in the private sector to develop diagnostic tools and reagents on large scale. After ramping up the testing capacity, the government turned its focus towards screening. Drive-through testing and phone-booth style walk-in testing centres managed to collect samples efficiently for testing.

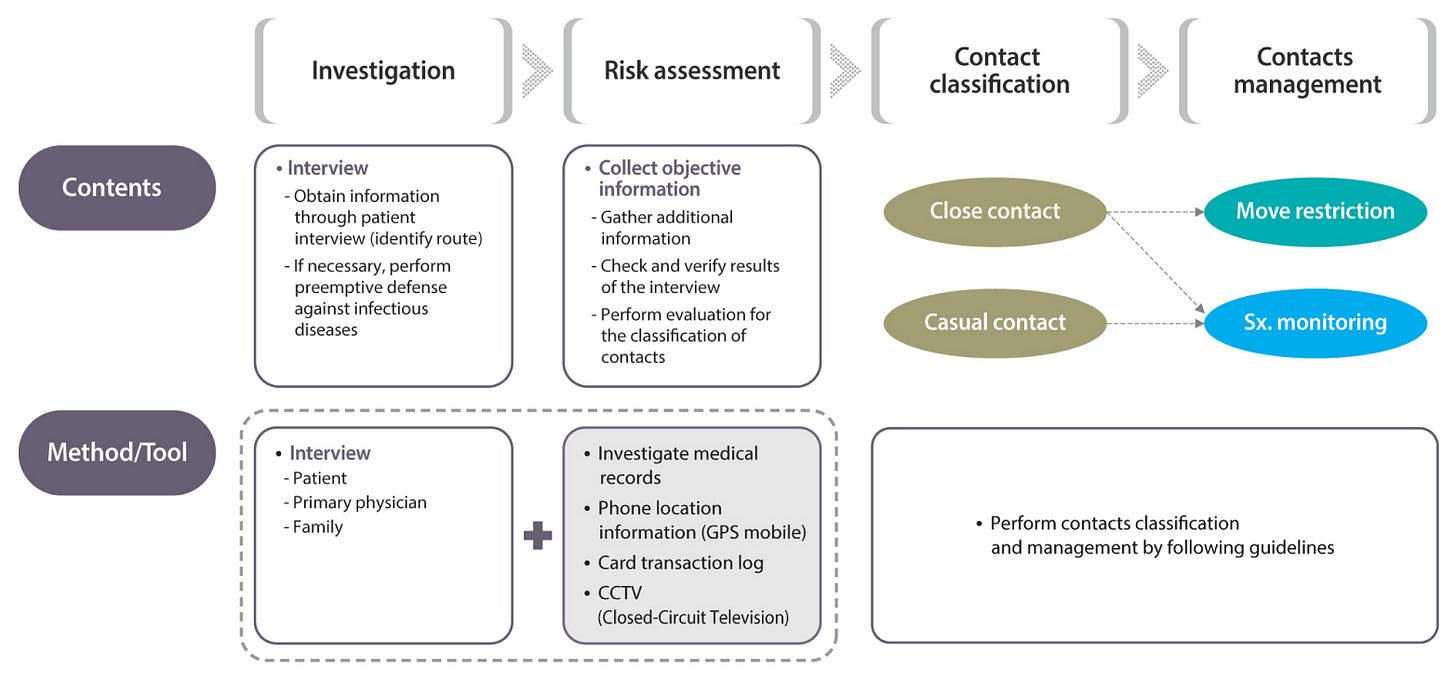

Containment: The Korean government transformed public facilities and training centres of private companies like Samsung and LG into isolation wards. The scale and the pace with which these temporary wards were set up helped admit thousands of people in the month of March. Contact tracing was aggressively done by the Korean government. After the outbreak of MERS, the legal structure is such that the government can use private data of the citizens to trace the spread of the virus. In Korea, data form credit card transactions, GPS data and CCTV footage were used for contact tracing.

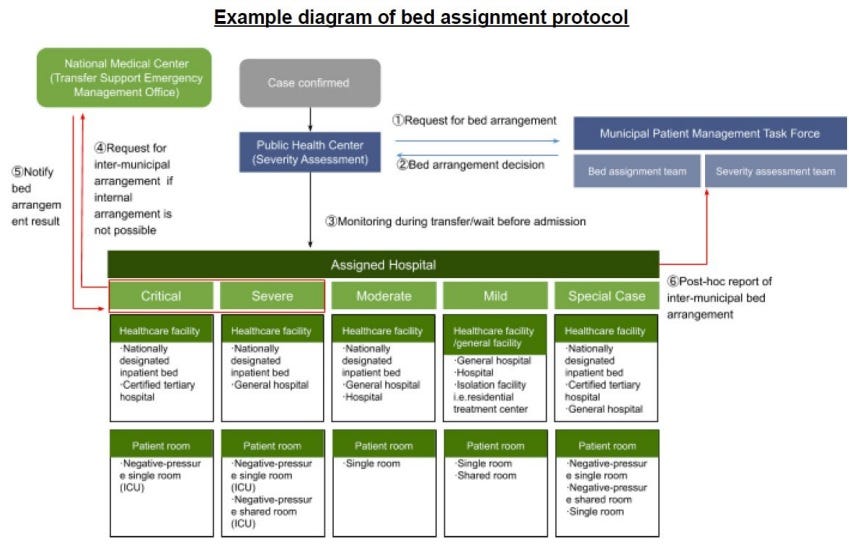

Treatment: The Korean administration focussed its interventions on high-risk groups such as people older than 65 years, people having chronic diseases, pregnant women etc. Because of the shortage of beds the health officials developed a triage system using a Brief Severity Scoring System to classify patient illnesses as mild, moderate, severe, or critical. Mildly ill patients were sent to community treatment centres where they were closely monitored, moderately ill patients were sent to community hospitals, and severely or critically ill patients were hospitalized at tertiary hospitals equipped to provide intensive care. It was this bed assignment protocol that helped the health officials to deploy the resources efficiently to treat the patients. In the case of bed shortage for severe or critically ill patients, the Transport Support Emergency Management Office would ensure proper transfer of that patient to a different region/hospital with beds.

Vietnam’s success also lies in her early detection and containment strategy. Since its economic reforms in the 1980s, Vietnam has invested a lot in public health systems.

These investments have paid off with rapidly improving health indicators. Between 1990 and 2015, life expectancy rose from 71 years to 75 years4, the infant mortality rate fell from 36.9 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1990 to 16.5 deaths in 2018,5 and the maternal mortality ratio plummeted from 139 deaths per 100,000 live births to 54 deaths.6 The 2018 immunization rate for measles in children ages 12 to 23 months is over 97 percent.

Vietnam has a history of successfully managing pandemics: it was the first country recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) to be SARS-free in 2003, and many interventions Vietnam pioneered during the SARS epidemic are being used to respond to COVID-19. Similarly, its experience with epidemic preparedness and response measures may have led to greater willingness among people in the country to comply with a central public health response.

Vietnam ramped up its testing capacity very quickly. When the Ministry of Science and Technology, in January, met few virologists and asked them to start developing diagnostic test kits, the publicly funded institutions developed 4 diagnostic tests. The private companies then took the manufacturing of these kits on a different level. Subsequently testing sites were increased. The health officials focussed on testing people from the clusters where the number of positive cases was more.

Vietnam used a very different strategy for contact tracing. The contact tracing was based on the degrees of contact from the infected person (F0). The person who would have come in contact with F0 would be traced (F1) and then F2, F3 and so on and so forth.

The process in Vietnam worked as follows:

Once a patient with COVID-19 is identified (F0), local public health officials, with support from health professionals, security officers, the military, and other civil servants, work with the patient to identify who they might have been in contact with and infected in the past 14 days.

All close contacts (F1), defined as people who have been within approximately 6 feet (2 meters) of or have prolonged contact of 30 or more minutes with a confirmed COVID-19 case, are identified by this process and tested for the virus.

If F1s test positive for the virus, they are placed in isolation at a hospital—all COVID-19 patients are hospitalized at no cost in Vietnam, regardless of symptoms.

If F1s do not test positive, they are quarantined at a government-run quarantine center for 14 days.

Close contacts of the previously identified close contacts (F2s) are required to self-isolate at home for 14 days.

Based on the epidemiological evidence from the clusters, Vietnam imposed targeted lockdown. Hence South Korea and Vietnam successfully flattened the curve because the outbreak was detected very early, it was monitored well, more number of tests were performed, effective contact tracing helped contain the virus and meaningful partnerships with the scientific community and the private sector were forged.

Impact of lockdown on lives and livelihoods

According to the latest study by the Centre of Sustainable Employment at Azim Premji University, Bangalore, the lockdown has resulted in a massive increase in unemployment, reduction of earnings among the informal workers and concerns regarding food security and relief coverage. The report is based on a survey of around 5000 respondents across 12 states. According to the researchers at the Blavatnik School of Government, the lockdown measures in India were one of the strictest pandemic containment measures in the world. This has led to massive levels of economic distress, loss of livelihoods and food security concerns.

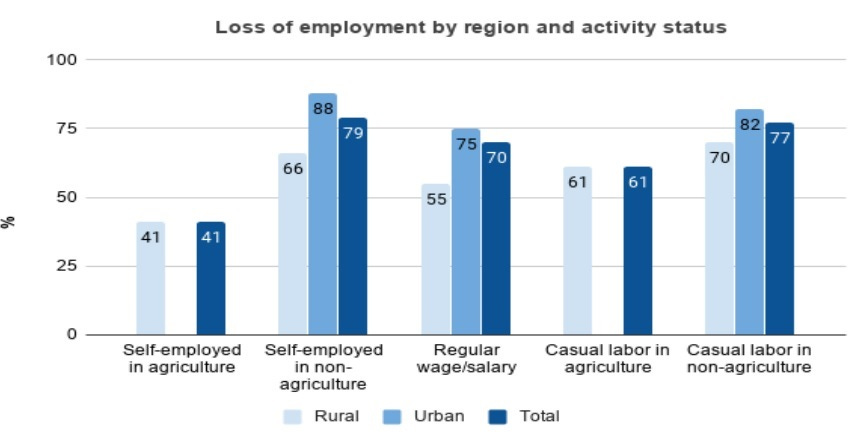

Nearly two-thirds (66%) of the respondents from the sample of the study (n=5000) claim to have lost jobs due to the lockdown. Most of these job losses are in urban areas. Around 88% of workers who were self-employed in urban areas lost employment. Similarly, nearly 82% of workers employed in casual labour in urban areas lost their livelihoods as a result of the lockdown.

A very similar pattern can be seen in the findings of the survey conducted in Delhi-NCR by the National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER). The construction labourers and other labourers were hit the hardest as 72% of construction and 77% of other labourers did not get work in the months of April and May. The sample size for this survey was 3,500 households spread across Delhi-NCR.

Finally, economist Abhijit Banerjee has a message on how economics can regain its credibility as a discipline.

Goodreads:

1) James C. Scott honoured for cross-disciplinary contributions

2) Bihar: With over 2 Crore Masks Made, How Jeevika Didis are Helping in the COVID-19 Fight

3) Can we build a politics of hope?

5) India accounts for nearly one-third of the world’s missing women: United Nations

informative, liked the Korea & Vietnam comparison