Dispatch #30: Systemic Backsliding of Democracy in India

In this dispatch we will go through the arguments put forward by Oxford professor Tarunabh Khaitan in his essay titled 'Killing a Constitution with a Thousand Cuts'

Recently, commentators on Indian politics have argued that the single most predicament facing Indian democracy is an ‘authoritarian executive’ that enforces its writ on the citizens using brute majority. The citizen has been reduced to a ‘principal’ who is at the receiving end and is voiceless. A citizen who tries to raise her voice is either called an ‘anti-national’ or ‘parjeevi’ (parasite).

In a liberal democratic constitution an executive is accountable to its citizens, to the parliament, to the judiciary and also to other state institutions that seek accountability from the executive. This is the fundamental tenet of a bicameral parliamentary system.

The makers of the Indian constitution had provided enough safeguards to protect democracy and constitution in terms of political accountability of the executive.

According to V-Dem Institute, political accountability is defined as:

A constraint on executive power and comprises the mechanisms for holding an agent accountable and the means to apply sanctions when a principal (citizens) transfers decision making power to an agent (the government).

There are 3 types of accountability in a liberal democracy that put checks and balance to the executive- vertical, horizontal and diagonal.

Vertical (electoral) accountability: institutions and actions that make the government accountable to the people through elections or political parties.

Horizontal accountability: the checks and balances that are in place and used by the legislative and judicial branches of government to hold the executive branch accountable.

Diagonal accountability: means that media and civil society have to hold the government accountable, through, for example, the spread of information, publicity, protests, and other forms of engagement.

In his latest essay titled ‘Killing a Constitution with a Thousand Cuts’, Oxford University professor Tarunabh Khaitan describes how the BJP government in 2014 has subtly and systemically undermined all kinds of accountability seeking mechanisms for the executive. He calls it killing with thousand cut because the government, after it came to power in 2014, has dismantled all the arrangements that could have put teh executive actions under scrutiny. In its first term (2014 to 2019) the dismantling was gradual and subtle as compared to ‘full-frontal’ attack on the democratic institutions in its second term (2019 onward).

According to Khaitan, the two strategies deployed by the government since 2014 to bypass all three forms of accountability are:

a) Executive aggrandizement: Where the institutions of accountability are undermined by the political executive

b) Party-state fusion: When the institutions are captured by the party loyalists who have the same ideological inclination as the ruling political party.

Explaining the types of accountability that a liberal democratic constitution seek from the political executive, Khaitan writes:

In the first of these axes, democracy seeks electoral – also called vertical – accountability from the political executive. The executive is required (either directly, as in presidential systems, or indirectly, as in parliamentary systems) to periodically seek the endorsement of the people through free and fair elections.

The second axis of accountability for the executive is therefore institutional or horizontal. To secure this, a constitution subjects the actions of the executive to the scrutiny of several other state institutions, including a legislature, a judiciary, and various “fourth branch” institutions that include an auditor general, an electoral commission, a human rights watchdog, an anti-corruption ombudsmen office, a chief public prosecutor, and so on.

The third dimension of executive accountability is discursive: to continue with the spatial metaphor, we could call this diagonal accountability.19 This is the accountability of the executive (along with other state institutions) to justify its actions in a public discourse with what is called “civil society.” Particular civil society institutions, which play a key role in ensuring this discursive accountability, include the media, universities, campaign groups, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), trade unions, religious organizations, and charities.

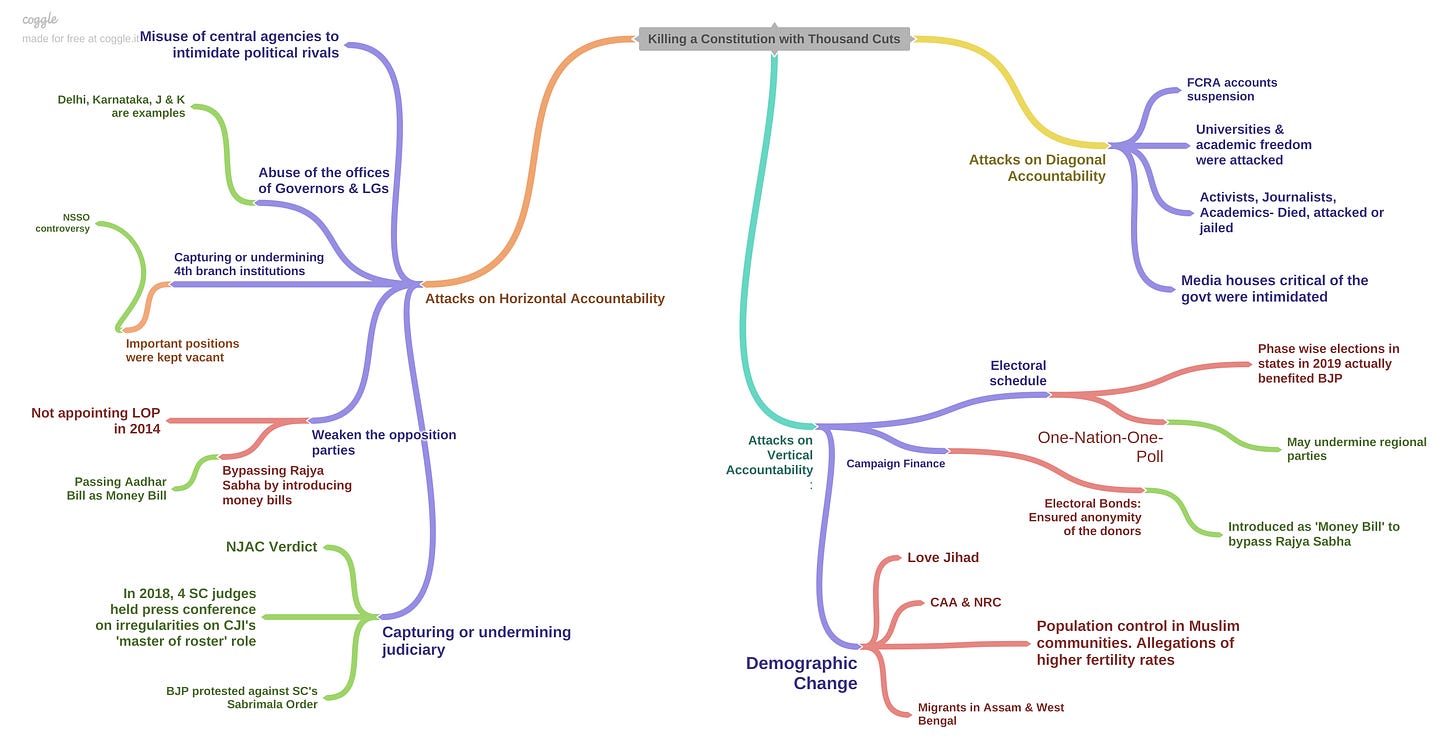

The mind map below sums up Khaitan’s arguments in the essay. It provides a framework to understand how the BJP government undermined all three forms of accountability since it came to power in 2014.

Khaitan concludes his essay by writing, “Ultimately, the three modes of seeking executive accountability ensure that today’s political losers can be tomorrow’s winners. They provide political insurance to the losing side, giving them hope of future victories, and thereby securing their consent to play by the rules of the democratic game and resolve disputes politically rather than violently.Undermining democratic checks ultimately risks authoritarianism, and is therefore inefficient as well as unpatriotic. The people of India publicly and communally reciting the Preamble to their Constitution in continuing protests that have erupted across the country since December 2019 appear to understand this, even as India’s dithering institutions fail to grasp the enormity of the stakes, or are unable or unwilling to do very much about it.”

While Khaitan’s essay focused on the accountability seeking mechanisms form the political executive under the current ruling dispensation, K K Kailash in his latest article talks about how centralisation by the government has undermined Indian federalism.

Kailash writes, “When the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led National Democratic Alliance claimed in 2014 to inaugurate a new era of federalism, the gradual emptying of its meaning was not expected. By 2019, centralisation moved to a new level and was quite unlike anything in the past. There was little use for the traditional centralising elements like the use of the office of the governor and Article 356 of the Constitution (which previous governments in New Delhi used) as the BJP came to be in power in a number of states. Encouraged by the congruence of the party in power in the centre and the states, the union government began to treat states as line agencies or the delivery arms of central ministries and departments, constraining the states' political and financial autonomy. Along with this administrative centralisation, there is also a political and cultural homogenisation logic at play. This new phase of centralisation gets its legitimacy from an economic rationale, which pushes for particular delivery models and centralisation in specific services, ostensibly for the sake of greater efficiency.

The BJP's long-held ideas about the nation shape the contours of the new diminished federal order. The BJP subtly uses an economic and administrative justification as a vehicle to carry forward its political and cultural logic of a One Nation, One India. The central element in the federal idea of allowing differences to flourish has become an object of criticism and is systematically delegitimised. Uniformity is now preferred over diversity and political expressions of state-based interests are seen as hurdles to the making of One India.”

He further adds, “Federalism was a key institutional mechanism for “holding-together” India’s enormous socio-cultural and multinational diversity. It has been a key factor in conflict management and democratic stabilisation, and has provided tools for constant adjustment to accommodate multiple and diverse demands. To counter centripetal movements and motivate greater participation in the democratic processes, India experimented with a variety of mechanisms and practices, including granting special status to states with subsidies and fiscal incentives, putting constitutionally protected asymmetries in place, creating centrally administered territories, elevating centrally administrative territories to statehood, carving out new states from existing ones, and forming sub-state autonomous councils (Arora 2010). In India's federal experiment, there was an implicit understanding that nation-building is a work in progress that required innovation and even the disruption of given templates.”

Kailash has very nicely talked about the legacy of BJP’s ‘One Nation, One India’ project. He writes, “The One Nation project of the BJP derives from a pre-occupation with national unity and territorial integrity. The theme of unity was central to BJP’s forerunner, the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, a party born in the wake of Partition. The theme cashed in on the memories of Partition and the religious divide, which allowed for claims on behalf of a so-called “threatened majority”. Taking this idea forward, the Jana Sangh rejected the state-nation arrangement and pushed for the nation-state model where “people of a country become a nation only when they are united by one common culture” (Bharatiya Jana Sangh 1973). Related to this idea was a constant call for “Indianisation” to achieve and maintain unity. Accordingly, people were encouraged to identify with a common cultural identity and voluntarily assimilate into the dominant culture and give up their distinctive, ‘foreign’ ways of life. The existence of alternate identities was seen as a shortcoming in the building of a nation.

In this framework, there would be no minorities and majorities based on religion, and special privileges in the name of "protection" were seen as means of “appeasement”. The Jana Sangh was unsurprisingly critical of special and asymmetrical provisions to particular regions. It held that when fair procedures (which treat everyone equal) were in place, the popular will would be expressed, and that the political outcomes of this expression of popular sovereignty were not only desirable but also fair. Contrary to the demands of substantial equality, there was an implicit belief that the majority community had the legitimate right to advance itself, lest it turned into a minority.”

The author concludes by arguing, “The One Nation idea rides on an economic and administrative rationale that favours greater centralisation in particular domains. It should however be seen as another element of what Palshikar (2004) underlined as the shift of the majoritarian middle ground to the right. It is an attempt to reimagine the nation in the majoritarian vision, where uniformity is preferred over plurality.”

Senior journalist Aunindyo Chakravarty writes that contrary to the belief, the current Jat farmers protests, in and around Western Uttar Pradesh against the three farm laws may not adversely impact BJP’s electoral gains. But what explains the government’s paranoia surrounding a ‘toolkit’?

Shoaib Danyal asked the same question to some political scientists. Here are some of the responses:

1) Neelanjan Sircar- “It is not only about winning elections, it is about demonstrating control over all facets of space. The fact that farmers can still sit there [in Ghazipur] in spite of, say, [Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister] Adityanath’s efforts is a huge problem for the BJP. The perception of effectiveness on one side of the coin and fear on the other are dependent on the idea that this party controls every facet of social life. Once the aura gets pierced, it doesn’t take time for a slide to start much like CPI(M) in West Bengal. This is why it might seem puzzling that the BJP cares so much about Rihanna or Greta Thunberg tweeting when they can’t influence elections, but this creates the fear that the BJP will not be in charge of the narrative.”

2) Tariq Tachil- "BJP’s nature as a populist party drives it to enact big policy decisions, including the farm laws, without efforts at consensus-building and negotiation at the formulation stage. Populist governments see their moral authority as rooted in their direct connection with voters and their electoral victories. However, this approach often puts the government in a position of having to counter an unanticipated reaction, either through ex-post negotiations and policy shifts, or crackdowns. Even if protests and dissent don’t have an immediate electoral impact, they might open the door for a more gradual erosion of popularity. The double-edged sword of reliance on a top leader’s popularity is that such erosion can be ill-afforded. Perhaps this threat helps explain the government’s often heavy-handed responses to domestic protestors, and hair-trigger sensitivities to international celebrity tweets.”

3) Milan Vaishnav- “In these sorts of regimes, there is always a period of oscillation between escalation and de-escalation, since remember, you are still confined to the boundaries of electoral politics. You can do something that charges up your base but that creates liabilities in other places – the Citizenship Amendment Act is a classic example. It’s then that you might have to beat a strategic retreat and wait till the next time you have an advantage.”