Dispatch #31: Weekend Linkfest

Here is a curated list of a few good articles from the world of policy, politics and development.

1) Prosperous Maharashtra, Karnataka hide a disparity within. Development is not for all:

In this article, Vikash Vaibhav of Dr B R Ambedkar School of Economics and Varun Das of Delhi School of Economics, have written about their latest research on intra-state disparity within prosperous states like Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra and Karnataka.

The authors found that in Karnataka and Maharashtra, a major chunk of economic activity is been driven by one or two cities as compared to Tamil Nadu that has a broad base of economic activity across several districts.

They write, “Maharashtra and Karnataka show that economic growth has been mostly concentrated in only a few selected pockets within a state, capital and adjacent districts. More importantly, this unequal contribution of districts towards the states’ output has been persistent over time, suggesting that development has been geographically ‘unbalanced’. Tamil Nadu, on the other hand, has dealt with inter-district disparity in a much better manner.

These findings have important policy implications. Regional economic disparity is evident even in prosperous states. Economic growth or prosperity in a state is usually concentrated around the capital district. The state governments need to actively intervene so as to ensure that each district or region participates equitably in the state’s progress. Otherwise, the relatively under-developed region may start feeling alienated. The situation may aggravate to the extent that the demand for a separate state for the region intensifies, for instance, the demand for Vidarbha in eastern Maharashtra.

A solution may be to develop all regions within a state based on its comparative advantage, and produce goods for domestic exports. It may not be a far-fetched dream in a country like India where the government still wields a lot of economic power, especially on the production side.”

2) Two Papers on Judicial Bias in India:

Alok Prasanna Kumar talks about two recent studies on judicial bias in India. The first study by Nitin Kumar Bharti and Sutanuka Roy, titled ‘The Early Origins of Judicial Bias in Bail Decisions: Evidence from Early Childhood Exposure to Hindu– Muslim Riots in India’, finds out that the district judges in UP who have experienced communal riots during their childhoods are more likely to deny bail as compared to those judges who have not experienced any riots.

The second study by Sam Asher and others, titled ‘Measuring Gender and Religious Bias in the Indian Judiciary’, contradicts the first study where the authors did not find any in-group bias among the judges when it comes to convictions in criminal cases in trial courts.

Alok writes, “That said, the results in Bharti and Roy’s paper do not contradict Ash et al dramatically. As earlier pointed out, they are looking at different stages of a litigation process. Bail hearings often take place before the investigation is complete, and the material before the judge is preliminary. Judges are not required to examine evidence in depth, or speculate on the outcome of the trial when deciding a bail application. The concern is generally whether the accused is prima facie guilty, is needed for further investigation, is likely to flee trial or tamper with witnesses, or might re-offend if released, among other factors. On the other hand, conviction requires the prosecution to prove its case beyond reasonable doubt. This requires marshalling of evidence and witnesses on the part of the prosecution—a significant challenge in and of itself. Even if the defence leads no evidence, it is enough to acquit if the defendant is able to raise reasonable doubt in the mind of the judge about their guilt. Proving guilt beyond reasonable doubt and getting a conviction therefore is dependent on a number of external factors beyond just the judge’s own views or personal predisposition. Even if there is systematic evidence of bias, it might prove hard to unearth in the context of convictions and acquittals given the various factors that go into the final verdict in a criminal trial.”

3) India’s democratic exceptionalism is now withering away:

Ashutosh Varshney in this very important piece on democratic backsliding in India writes, “India’s democratic exceptionalism is now withering away. Democracies do not charge peaceful protesters with sedition, do not have religious exclusionary principles for citizenship, do not curb press freedoms by intimidating dissenting journalists and newspapers, do not attack universities and students for ideological non-conformity, do not browbeat artists and writers for disagreement, do not equate adversaries with enemies, do not celebrate lynch mobs, and do not cultivate judicial servility. A democracy which speaks with one voice, which elevates citizen duties over citizen rights, which privileges obedience over freedom, which uses fear to instill ideological uniformity, which weakens checks on executive power, is a contradiction in terms. For democratic theorists, these are all signs of creeping authoritarianism, not of democratic deepening. Elections alone cannot define what it means to be democratic.”

4) From Lasting Damage To Resilience- How Riots Affect Children:

The mental and psychological impacts of riots on children is an under-researched area. This article by India Spend tries to fill that gap.

The article suggests, “Evidence suggests that while natural disasters impact children deeply, the impact of man-made disasters could be worse. A comparison of children aged 8-15 affected in the 2002 Gujarat riots (171) and by the 2001 Bhuj earthquake (128) against a control group of 351 children that had experienced neither, found that "children exposed to violence were psychologically more affected", according to a 2013 study. Results showed that 7.6% of the earthquake-affected children displayed "clinically significant mental health problems"; the figure was 38.7% for riots-affected children. In the earthquake sample, 24.8% of children met the criteria for probable post-traumatic stress disorder, compared to 27.3% of children from the riots sample.

"It was the nature of witnessing--[riots-affected children] had seen family members killed, mutilated--purposive, harmful actions which emotionally disturbed them," said Manasi Kumar, a faculty member at the Department of Psychiatry, University of Nairobi, who authored the study. "In riots, you know who did what. Neighbours turned on each other and trust was violated in a very different form," Kumar told IndiaSpend.”

5) Did MNREGA cushion job losses during the pandemic?

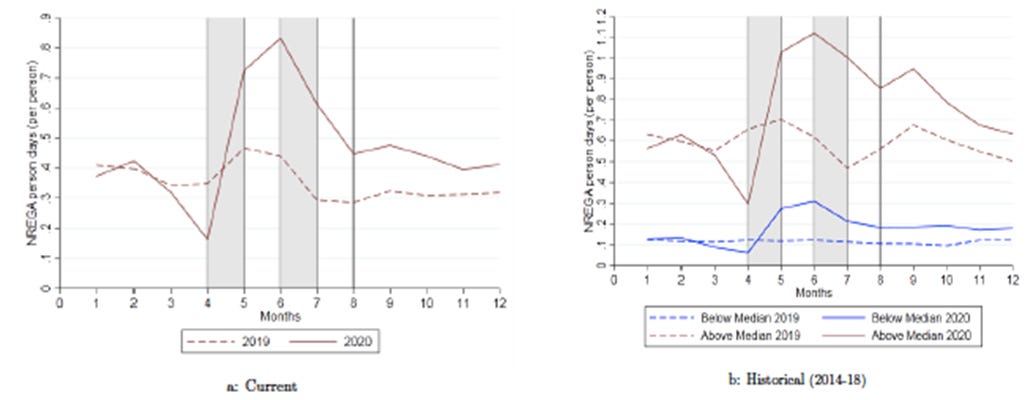

In this article, Farzana Afridi, Kanika Mahajan and Nikita Sangwan, write how in 2020 districts with higher State capacity (measured as the average number of person-days per rural inhabitant provided under the scheme during 2014-2018 in a district) were able to provide more MNREGA person-days per rural inhabitant.

They write, “A closer look at the data (Afridi, Mahajan and Sangwan 2021) shows that the increase in person-days of work provided in 2020 was higher in districts with above-median historical State capacity to provide MNREGA person-days – measured by the average number of person-days per rural inhabitant provided under the scheme during 2014-2018 in a district. Districts with historically higher State capacity to generate person-days under MNREGA not only generated more person-days in 2020 under the scheme but also witnessed a sharper absolute rise (from 0.53 to 1.12 person-days per rural inhabitant) in person-days generation between March and June 2020, compared to historically low performing districts (from 0.09 to 0.31 person-days per rural inhabitant). Hence, State capacity to utilise public funds has been a critical determinant of governments' ability to respond quickly to economic crises.”

6) Joblessness, Politics and Neo-religiosity in Uttar Pradesh:

In this brilliant paper, sociologist Satendra Kumar talks about the religious and political preferences of educated and unemployed youth from various socio-economic backgrounds in Allahabad and Meerut cities.

Satendra writes, “While there is a surge of aspirations across UP, the lack of job opportunities is also an emerging reality. However, the relationship between availability and preference for a job is not straightforward. Preference for a job is shaped by local cultural values and social relations such as caste, class, and gender. Youth in Allahabad and Meerut lived largely with their parents and were economically dependent on them. They were well integrated with their families, kin, and caste members, and the expectations of these relationships shaped their aspirations. Further, cultural values associated with manual and mental work played a crucial role in occupational choices. Upper caste Brahmin culture negatively regards manual work but highly values mental work. Educated unemployed young men do not just take up any available job but look around for one which would raise or maintain their status and prestige in their societies. Most importantly, in the absence of an expanding industrial economy, secure and well-paid, but less demanding, government jobs are highly valued across castes and classes. The spectre of joblessness has heightened the sense of insecurity among youth and has deepened their identity crisis. To cope with this insecurity, they engage with religion in different ways. Some of them treated religion as a form of spirituality. These youth claimed that they were different from their parents who were more superstitious and ritualistic. Some educated unemployed mostly upper caste and middle-class youth considered religion as a marker of their identity in the global discourse, particularly in relation to the West. They used vegetarianism as a tool to bash others, especially Muslims and beef eaters. Further, Hinduism has been developing congregational tendencies that have given space to the upward mobile Dalit and OBC caste groups to express their religious sentiments and claim the Hindu middle-class identity. These congregational activities also provide spaces to youth masculinities and criminalities (Hansen 1996). My study suggests that events such as the Kavad Yatra, Bhagwat Katha and Durga Puja are being used by the RSS and other right-wing Hindu organisations to indoctrinate young men. These organisations have been using these events as opportunities to further their cause by blending these spectacles with Hindu nationalism.”

7) BJP is using lesser-known figures from medieval history to further its politics:

Sociologist Badri Narayan writes about BJP’s strategy to invent and co-opt medieval period icons of OBC, MBC and other marginalized communities to further its politics.

He writes, “The politics of Hindutva tried to carve a space for its idea of cultural nationalism by evoking a pyramid of icons and cultural symbols. The base of this pyramid emerges through their work with religious symbols like Rama, Krishna and Buddha. At the second level, it has explored the symbolism of medieval kings — who defeated or fought Muslim “intruders” — such as Raja Suheldev, Gokul Jat, Baldeo Pasee, etc. Simultaneously, it is exploring the marginalised aspects of the Gandhian-Nehruvian national movement and incorporating them into its own larger discourse of cultural nationalism. The BJP and Hindutva forces are constantly appropriating as many icons and legacies as they can for their political garland. The major strategy of this management of memories of Hindutva politics is to explore marginalised and oppressed narratives within the secular meta-narrative of society, culture and politics and retell them. If someone closely watches the politics of the BJP and Hindutva family, they may understand that they have identified “memory zones” based on the influence of heroic symbols — such as Suheldev in central and eastern UP and Gokul Jat in western UP. Based on these memory zones, the BJP-led government and party plan activities around “memorial politics”. They are also exploring caste and community-based heroes and icons to facilitate their politics among certain communities.”