Dispatch #37: It's a surge; it's a wave; it's a wall

As the second wave of Covid-19 wreaks havoc in India and our health system gets collapsed, let's look at the numbers to see how it unfolded

It won’t be an exaggeration to say that this is the cruelest summer in India after 1947.

With daily new confirmed Covid-19 cases just surpassing the 3 lakh mark, India is second after Brazil to have the maximum number of daily confirmed cases. The second wave that started from March doesn’t even look like a wave, it looks like a wall. A formidable one. Our healthcare system has collapsed, care providers are stretched and exhausted, people are gasping for breath and the crematoriums are running 24 x 7.

Around 140 districts in India have a positivity rate of around 15%. According to the WHO, the positivty rate should remain below 5%. These rates are alarming in Delhi and Maharashtra at 30% and 16% respectively.

The chart below shows the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases per day.

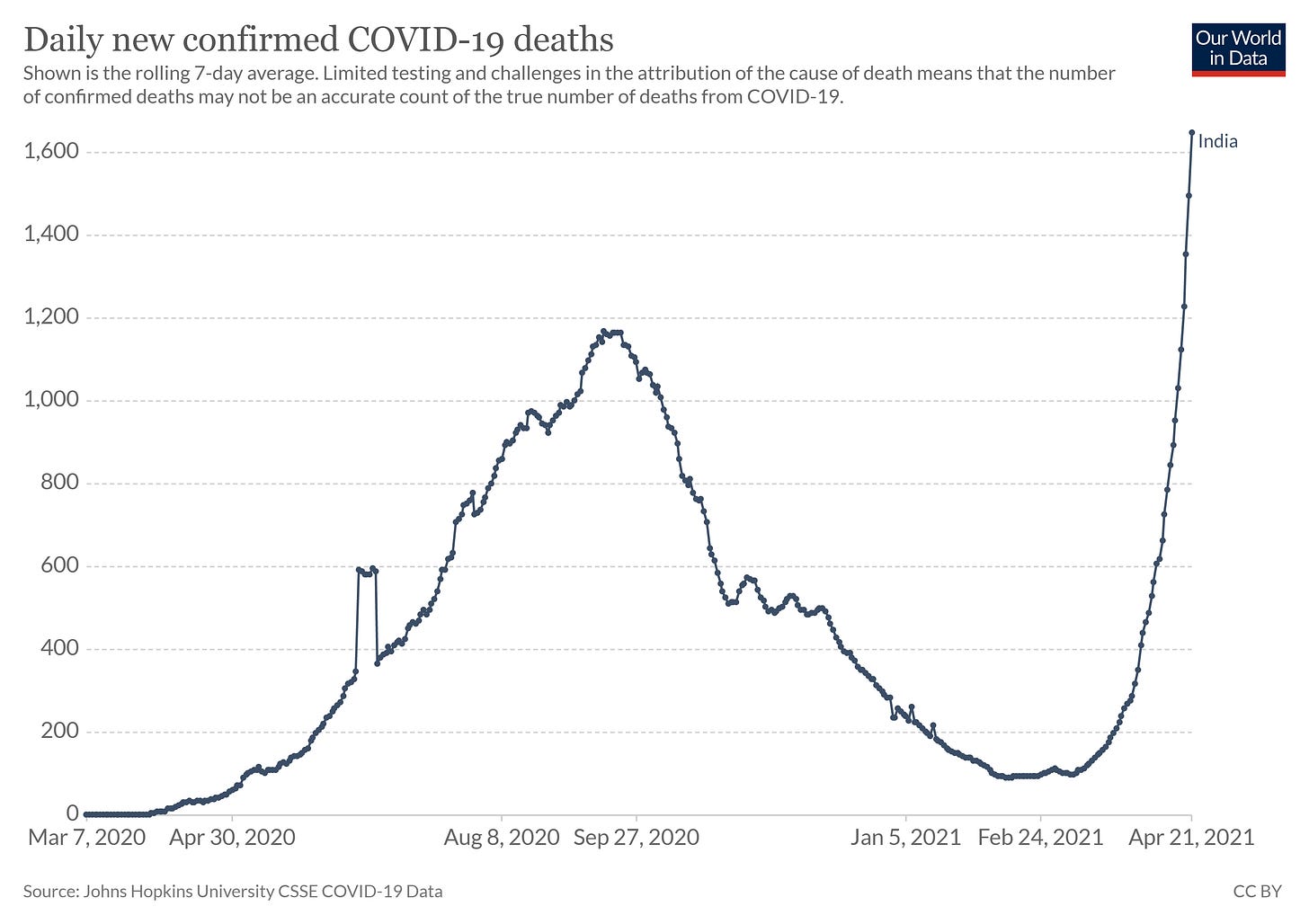

The daily number of confirmed deaths is also following the same pattern as the daily confirmed cases. The actual number of deaths in India is heavily under-reported. In states like Uttar Pradesh, the official number of daily deaths speaks a very different story than the ground reports of crematoriums and burial grounds running short of spaces and handing waiting list tokens to the family members of the deceased.

On the under reporting of Covid-19 related deaths, this FE article says, “In India, there has been a set SOP about how the local officials will report a Covid death. After a person dies, the members of the local task force unit reach there. Now, the critical aspect is ‘comorbidity.’ In India, if a person had a pre-existing disease, chances are that her/his death will not be recorded as a Covid death. This was also pointed out by Gujarat Chief Minister Vijay Rupani. When asked about the visuals circulating on social media, though he admitted about the increased number of deaths yet he didn’t say that most people are dying due to Covid-19 infection.”

FT’s John-Burn Murdoch and Murad Banaji have compared the official death statistics with the cremation data form the local newspapers in India and found out that the actual number of deaths in India could be 10 times more than the official data.

John has summed up his article in this Tweet thread:

The death registration and its certification has always been a problem in India. Over the years, although the death registrations have increased to around 90% in 2018, yet it leaves 10% which in absolute terms is a big number. In addition to that only a fraction of these registered deaths are medically certified. So the cause of deaths is something which is a challenge in India and it has come out in a big way during the present Covid-19 crisis.

According to the estimates by the IHME, the second wave in India will peak in mid-May with daily Covid-19 related deaths to be somewhere around 5000 to 6000. We will see a decline only towards the end of May.

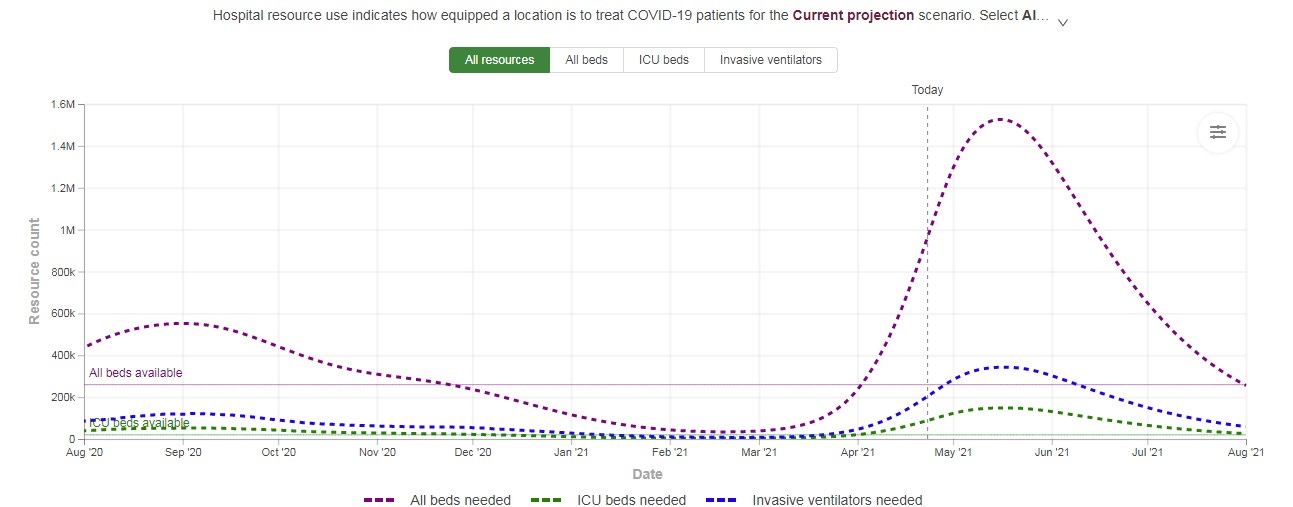

The healthcare infrastructure, which is under severe stress right now, might be looking at the imminent collapse by mid-May if the governments and private players do not ramp up their infrastructure.

Epidemiologist Bhramar Mukherjee says, “Even if the peak is reached in May, it will take a while for the cases and deaths to come down to a level where we can have confidence in resuming normal life. We can only do that if there is a high alert public health system in action which involves genomic sequencing. Right now regardless of the models, we know a tidal wave is hitting us and we have picket fences to beat it. We need international coalition, every possible help to increase oxygen supply and produce vaccines. Vaccines work and can save lives.”

Health economist Rijo M John says, “At 20%-25% TPR, we cold well be reporting 5L daily new cases in the next 3 weeks time which only takes about 20L to 25L testing. This is a more realistic testing target in the next 2-3 weeks given our current level of testing & its growth.”

India is running out of oxygen, Covid-19 patients are dying – because the government wasted time:

Early in the pandemic, it became clear that oxygen would be one of the most precious commodities in the battle against the virus. Yet, it took the Narendra Modi government eight months to invite bids for new oxygen generation plants.

On October 21, the Central Medical Services Society, an autonomous institution under the Union health ministry, floated a tender online calling for bidders to establish Pressure Swing Adsorption oxygen plants in 150 district hospitals across the country. The PSA technology separates gases from a mixture in the atmosphere to generate concentrated oxygen that can be supplied to hospital beds through a pipeline, negating the need for hospitals to buy pressurised liquid oxygen from other sources.

It seems unlikely that the delay in kickstarting the tender process was caused by a lack of funds: the outlay for 162 oxygen plants (12 plants seem to have been added later) is just Rs 201.58 crore. The money has been allocated from the PM-Cares corpus – the Prime Minister’s Citizen Assistance and Relief in Emergency Situations fund, which had received over Rs 3,000 crore in donations within four days after it was set up on March 27, 2020.

Now, with a deadly second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic sweeping through the country, the Modi government said in a statement on Thursday that another 100 oxygen plants will be established out of the PM-Cares fund. On the status of 162 oxygen plants for which contracts were given in 2020, all it said was that they were “being closely reviewed for early completion of 100 percent of the plants”.

As COVID-19 Cases Increased, Oxygen Beds Fell, Data Show:

When COVID-19 cases first began rising in India in March 2020, the government began identifying and adding dedicated COVID hospitals, dedicated COVID health centres and COVID care centres, public and private. From time to time, the government also put out data on how many COVID-19 beds were available in these facilities across the country, including ICU beds and oxygen supported beds for severe cases, and isolation beds for mild and pre-symptomatic cases. Only COVID hospitals and health centres offer all three types of beds.

By the time of the second wave, the health minister said, "the country has substantially ramped up the hospital infrastructure for management of COVID". There were 2,084 dedicated COVID hospitals, 4,043 COVID health centres and 9,313 COVID care centres in the country, per the accompanying Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) press release on April 9. These numbers all represent substantial increases since April 2020 (see chart below).

However, the pace of adding COVID hospitals and health centres decreased after the first wave peaked in September 2020, our analysis of health ministry data submitted to parliament and in press releases shows. Between December 2020 and April 2021, the number of dedicated COVID hospitals fell by 6%. Similarly, there was a 6% reduction in the number of dedicated COVID health centres, falling to 4,043 in April from 4,300 in December 2020. Only the number of dedicated COVID care centres increased by 5%, from 8,857 in December 2020 to 9,313 in April 2020. COVID care centres, however, are not equipped for severe cases, only COVID hospitals and health centres.

There were 255,168 oxygen-supported beds in the country on April 9, 2021, per the ministry. This is more than double the 115,134 million beds in May 2020, but 6% fewer since December 2020.

The decrease in itself is not necessarily a problem, say experts. "The key issue here is whether the government had capacity to ramp it up when we hit a surge, and so there needs to be flexibility in the system for this," said T. Sundararaman, former dean of the School of Health System Studies at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences in Mumbai, told IndiaSpend.

2nd wave coming- Serosurveys had raised red flags:

In January, when almost every state was reporting a decline in case numbers, Kerala was witnessing a surge — contributing almost half of all cases in the country. By mid- February, the confirmed cases in the state had crossed 10 lakh, second only to Maharashtra. This “outlier” trend in Kerala was not very well understood until the state did a serosurvey in January-February in all its 14 districts. It revealed that only about 10% of the state’s population had been infected. In other words, a majority was still susceptible.

But serosurveys are not a one-off exercise. As the nature and behaviour of the virus changes constantly, scientists say, there is a need for regular monitoring and surveillance through serosurveys in different population groups. This has hardly happened.

More concerning has been how the data was interpreted. The December serosurvey, whose results were announced in early February, for example, showed that barely 20 per cent of India’s population had been infected by then. That was a red flag: it meant a fresh wave was possible even though one couldn’t predict when.

However, some small very localised clusters in Delhi, Mumbai and Pune showing more than 50 per cent seropositivity received far greater prominence, and were used to explain why the numbers were falling.

“It was a classic case of cognitive bias,” said an official who did not want to be named. “We wanted to believe that the Covid is on its way out and so we interpret data to reinforce that belief. We were even talking about herd immunity for an entire city based on a serosurvey in a few neighbourhoods of a small sample.”

Key virus strain found in October but its gene study stalled; a new variety appears:

The Indian-origin double mutant strain of the coronavirus, B.1.167, that many experts say could be behind the rapid climb of the second Covid wave, was first detected way back in October 5 last year through genome sequencing of a virus sample.

Because both the mutations, E484Q and L425R, were located in the virus’s critical spike protein — that binds it to the receptor cells in the body. Its destructive potential should have raised immediate red flags and led to widespread gene surveillance to look for its prevalence and spread.

Instead, the genome sequencing exercise, already running at a snail’s pace, slowed down further between November and January due to lack of funds, absence of clear directives, and, possibly, also disinterest because of the steadily falling Covid curve.

Genome sequencing, the study of genetic structures of an organism and the changes happening therein, produces a wealth of information that can throw light on the origins of the virus, the routes it has taken to reach a particular geography and the changes, or mutations, that are making the virus stronger or weaker. Such information is crucial not just in designing control measures, but also in the development of drugs and vaccines. In fact, the early availability of gene sequences from China, United States and some other countries is one key reason why a vaccine could be developed in such a record time.

In India, however, genome sequencing crawled – in the first six months, India had barely done a few hundred sequences, when countries like China, the UK and US, had done several thousand and submitted these in public global depositories for scientists across the world to study.

Govt Knew Lockdown Would Delay, Not Control Pandemic:

About a week after Prime Minister Narendra Modi ordered the world’s largest lockdown on 24 March 2020, India’s leading medical research body told the government that the shutdown would have limited impact on the spread of the Coronavirus, preventing only 20-25% of infections that might eventually be detected at the peak of the pandemic.

This effect would be “temporary” unless the government took other scientifically recognised measures to curtail the pandemic, the government was informed.

Never made public, the information was based on an internal assessment carried out by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), the government’s premier agency of doctors, epidemiologists and other experts, tasked with addressing the Coronavirus outbreak, which claimed 652 lives and infected 19,818 by 22 April 2020.

“Generalised transmission to be obvious in coming days,” said Vinod K Paul, one of the government’s top advisors on the pandemic, in a presentation to government, based on the ICMR assessment, and reviewed by Article14.

The graphs in the ICMR study, on which Paul’s presentation was based, showed the lockdown would not have much impact on the likely cumulative number of infections in India.

“Best use of lock down is preparedness for” the measures, such as house-to-house screening and scaling up quarantine for those showing symptoms in affected communities, said Paul during the course of the presentation. These measures would substantially reduce the number of cases detected when the pandemic peaked and reduce infections as the pandemic wore on, Paul indicated.

Frustration In National Covid-19 Task Force:

Our review of the records of that meeting reveal how, having imposed an unplanned lockdown, the government was not prepared even with testing protocols to track down those infected with the Coronavirus, which causes Covid-19. Confusion apparently prevailed, and experts expressed their frustration at the lack of action, despite prior advice.

The records also show, while imposing the lockdown, the government had ignored recommendations from its top scientists. Instead of the current coercive lockdown, these scientists had advised “community and civil-society led self-quarantine and self-monitoring,” through their research in February 2020.

The research had warned of a large outbreak of the Coronavirus in India and indicated that the measures taken by the government until then were not enough. The scientists recommended ramping up testing and quarantining facilities, putting in place nationwide monitoring mechanisms and arranging enough protective resources for health-care workers.

Among the scientists who conducted this research were several later appointed to the government’s task force on Covid-19.

For more than a month, the research and advice of these scientists went unheeded. With no scientific strategy in place, an unprepared government, imposed—with a four-hour notice—a country-wide lockdown, which sparked a livelihoods and food crisis among the poor and migrants.