Dispatch #4: India's 'precocious' development pathway-Part 1

In this series, we will be looking at the unusual development pathway that India took and its consequences on the overall socio-economic development

In his classic 2006 EPW essay titled ‘Politics of Economic Growth in India,1980-2005’, Atul Kohli says that the economic growth story of the developing countries (read India, China and East Asian economies) has attracted a lot of scholarly attention. He argues that most of the debates to unpack India’s experience have been whether the growth was the result of pro-market policies or pro-business policies. In the two-part essay, Kohli persuasively argues that it was the pro-business reforms in the 1980s that put India on a growth trajectory, a decade before the 1991 economic reforms.

Rare though the cases are, the experience of rapid and sustained economic growth in a developing country has repeatedly provoked scholarly debates. The underlying questions are familiar: how did a country A or B (say, South Korea or China) get on the high growth path; and does the experience of A or B provides model or, at least, lessons for others. The main lines of the debate are also familiar: high growth resulted from the state’s embrace of a pro-market strategy, namely, a move towards limited state intervention and an open economy; or, no, the growth success was a product of an interventionist state, especially of a close collaboration between the state and business groups aimed at growth promotion.

-Atul Kohli, Politics of Economic Growth in India, 1980-2005 (EPW)

To support his central argument, Kohli puts out three sets of evidence in his piece:

1) After coming back to power in 1980, Indira Gandhi initiated the less noticed reforms to strengthen the state and business alliance and her anti-labour stance

2) Had it been pro-market reforms, the industrial growth would have been faster

3) The inter-state variations in economic growth prove that the state governments that were pro-business were able to attract private investments

India’s economic and social development story is a very intriguing one.

Many scholars and political scientists have written about this improbable 73-year old journey. With their meticulous research and hard-hitting analysis, they have unpacked India’s transition over several decades. Economist Arvind Subramanian is one of the observers of India’s development journey. He had spoken about the unusual case of India’s political and economic development earlier. He calls this India’s Precocious Development Model. Later, he and his team at the Finance Ministry put these findings in the Economic Survey of India-2016-17, when he was the Chief Economic Adviser.

In the American Economic Association’s winter issue of Journal of Economic Perspectives, Subramanian and economist Rohit Lamba have discussed India’s development model in an essay aptly titled ‘Dynamism with Incommensurate Development- The Distinctive Indian Model’. The central argument of the piece is that India’s robust economic growth since the 1980s has not been able to deliver results in the form of development as it was expected to deliver and there are structural factors that have led to this ‘incommensurate development’.

In the article, the authors have discussed factors that have led to this unusual scenario which they call the Precocious Development Model. Subramanian made this phrase fashionable by introducing it in the second chapter of the Economic Survey of India 2017-18. India’s development model is called precocious because a poor and a socially fractured country like India took an audacious step of carrying out economic development, political development and redistribution all at the same time, 73 years ago. No other country has ever undertaken such an ambitious project. In the West economic development preceded political development. In East Asian countries, autocratic regimes oversaw economic development. In these countries, political openness has been sluggish or has remained elusive in some cases.

India is an outlier because it both gave universal suffrage and undertook the task of economic development at the ‘stroke of the midnight hour’ when the country’s literacy rate was just 12%, average life expectancy was merely 32 years and was mired by several socio-economic fault-lines. The democratic Indian state and its public sector have seized the ‘commanding heights’ of the economy. It started redistribution rather than investing in basic provisionings like health and education because the demand for redistribution is high in a poor country with universal suffrage and low per capita income.

The economic development of a country depends upon its political institutions. There are two causal pathways that connect the two. One of the pathways is also called the ‘modernization hypothesis’. According to this hypothesis, countries start democratizing as their incomes grow and they sustain democracy only at higher incomes. Clearly, India has defied this hypothesis. The democratisation, political if not social, started right after the independence when the income levels were very low. 73 years since her birth, India’s democratisation has only deepened ever since then, except for a few instances of authoritarian impulses.

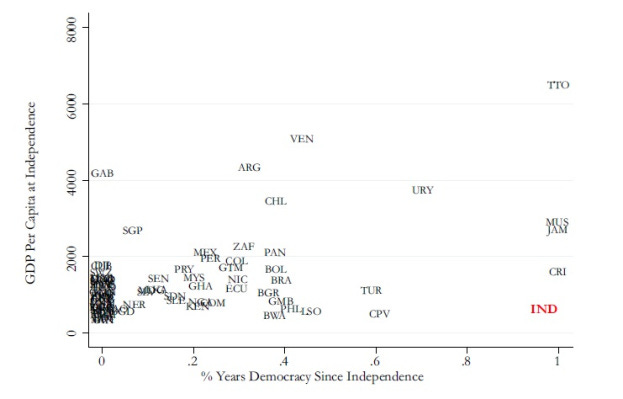

The chart above (taken from the Economic Survey of India) plots the percentage of years since independence when a country has remained a democracy on the x-axis and the income level at independence on the y-axis. India has remained a democracy even when it started as a poor country since independence.

‘Political scientists often describe as an anomaly how India has managed to sustain a democracy under inhospitable conditions of low income and literacy, a predominantly rural economy and major social cleavages’, the authors of the paper argue.

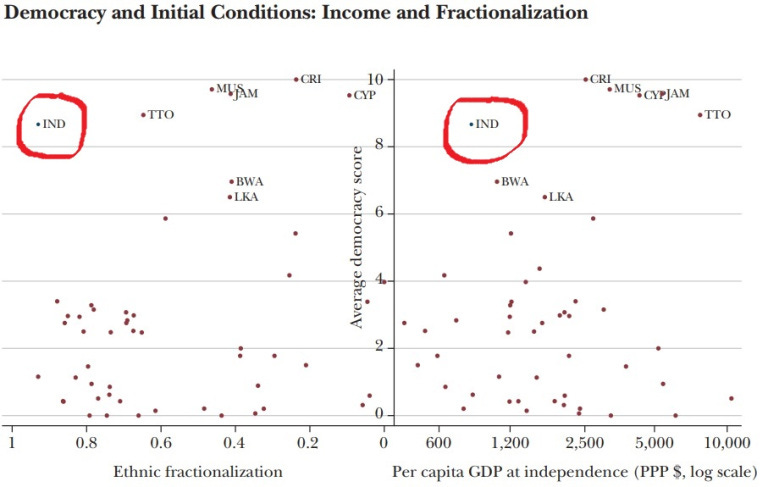

In the above chart, the authors have plotted the average democracy score which is a proxy of democratisation of a country on the y-axis. The per-capita GDP at independence and a score on ethnic fractionalization is plotted on the two sides of the x-axis. India stands out as an outlier. It has sustained democracy at low-income levels and high ethnic fractionalization.

The other causal pathway points out that the ‘inclusive’ democratic institutions promote economic growth and development since these institutions protect private property and adhere to the rule of law. Douglas North, Acemoglu and Robinson are the pioneers of this hypothesis. In their book ‘Why Nations Fail?’Acemoglu and Robinson used the example of the difference of economic activity along the 38th parallel line that divides North and South Korea. While the inclusive institutions in South Korea have led to prosperity, the extractive institutions in North Korea have led to an impeded development.

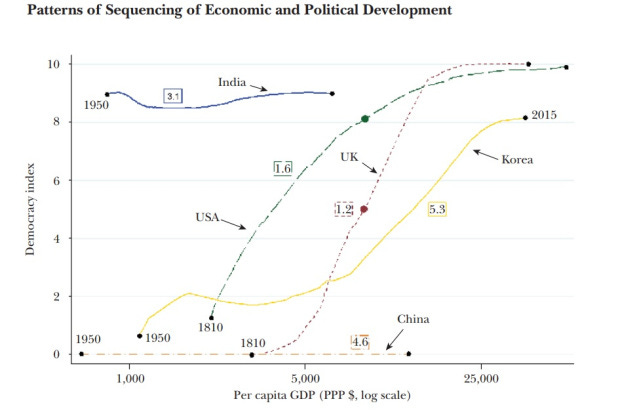

Subramanian and Lamba have analysed the political and economic development of the US, UK, India and East Asian countries in the paper. They argue that different countries have different sequencing of political and economic development. While in the US and the UK, economic development preceded political development, in East Asian countries economic development happened post-second World War, under autocratic regimes and the political development in terms of democratic institutions remains elusive. India turned this principle on its head. Indians got universal suffrage (a proxy for political development) after independence and economic development followed political development.

In the above chart, the authors have marked the trajectories of political and economic development of India, China, Korea, US and UK. It plots per capita GDP on the x-axis and a democratic index on the y-axis. The number in the box indicates the average growth rate. The big dots on the US and the UK curve indicate the point when these two countries granted the right to vote to the erstwhile disenfranchised sections of the society like the women. Both the US and the UK underwent a significant phase of economic development before becoming politically developed. Korea achieved economic development of the UK and the US at a very early stage but as the chart shows the democratic index is way below both the countries. China is an interesting case where economic development has gathered pace but political development is almost missing. India stands out in the chart because political development preceded economic development. However, economic development, when compared with other countries, remained stunted.

Arvind Subramanian and Rohit Lamba are not the first ones who have talked about the unusual sequencing of India’s political and economic development that has resulted in her taking a different development pathway, Ashutosh Varshney has also discussed the same theme in his 2013 book ‘Battles Half Won- India’s Improbable Democracy’. Varshney argues that political scientists are baffled to see India retaining her democratic nature against all the odds of low income and social development levels.

Hence, India defied the ‘modernization hypothesis’ with democratisation occurring before economic development. In addition to this, the social cleavages during and decades after independence remained very high. Hence the authors have also called it a ‘precocious, cleavaged’ model of development.

India had no other choice but to start redistribution at a very early stage of her economic development. In the Economic Survey of India-2016-17, Subramanian argues that because of high levels of democratisation within a socially fractured country the demand on the Indian state to redistribute increased significantly in the decades following independence. The Indian state, rather than providing broad-based services like health, education and sanitation, focussed on redistribution. Especially the distribution of clubbed goods to specific social groups. This redistribution was inefficient and relied heavily on weak state capacity. He has used the map given below to substantiate his inefficient redistribution claim.

The map on the left shows Indian districts that have a maximum number of poor and the map on the right shows almost the same regions where the redistribution to the same set of poor is a challenge. This is because of ‘exclusion errors (the deserving poor not receiving benefits), inclusion errors (the nonpoor receiving a large share of benefits) and leakages (with benefits being siphoned off due to corruption and inefficiency)’.

The chart below shows the income levels of different countries when they started redistribution. Typically, redistribution in other countries occurred late at an advanced stage of economic development when the income levels were fairly high and the state capacity was developed enough to ensure efficient redistribution. One can see a contrast between India and Korea. While Korea started redistribution when the per capita GDP was $ 20,000, India started redistribution when her per capita GDP was around $ 5,000.Also in the west, economic development led to the state providing basic services like health and education and at a later stage, they moved to redistribution. India flipped this logic as well. Redistribution started when economic development was just picking up and it mainly happened when the state capacity was weak and redistribution was leaky. This has resulted in the middle class ‘exiting’ the state, in Hirschman’s terms, since it perceived that they are not going to get basic services from the state and they have to perennially rely on private players for these services.

The consequence of this unusual pattern of economic and political development has resulted in, what the authors claim to be, ‘incommensurate development’. There are several dimensions of this incommensurate development:

1) Premature De-industrialisation and Precocious Servicification:

India skipped the low-skilled manufacturing phase and directly ventured into the services. This happened because of the disincentives provided to the manufacturing industries. The license raj and the labour laws not only raised the costs of the labour but also acted as disincentives for small industries to expand.

Traditional theories have placed a hierarchy on the “natural” order of economic development: first a structural transformation from agriculture to low-skilled manufacturing, then the next transformation to high-skilled manufacturing, and eventually services.6 India has turned this theory on its head by leapfrogging manufacturing and adopting a low and high skill-intensive services transformation. India has thus grown by defying, rather than deifying, its comparative advantage in abundant unskilled labor.

-Subramanian and Lamba, ‘Dynamism with Incommensurate Development (AEA)

India has not been able to re-allocate surplus labour from agriculture to manufacturing that requires less skilled workforce because there has never been a manufacturing sector of a scale that can absorb such a large workforce from agriculture.

While the share of agriculture in GDP in India, China and other developed countries have come down, its share in employment in India remains higher than the other countries.

In India, the share of manufacturing in GDP is far less than that in China and other developed countries. The East Asian economies started from low-skilled manufacturing, then moved to high skilled-manufacturing before moving on to services. The share of manufacturing in India is also very low as compared to China and developed countries. In fact, the share of formal manufacturing in India is abysmal.

The servicification of the Indian economy is evident from the chart below. The share of services in GDP in India is higher than China but the share of services in employment is not that much. The services sector absorbs only the skill-intensive workforce thus leaving a vast pool of unskilled labour that is stuck in informal manufacturing.

The contrast between India and other countries in their divergent structural transformations is striking. India’s employment share of manufacturing and services is much lower at a comparable income level; worse, highproductive formal manufacturing is even smaller. Thus, India’s dynamic and high-productivity activities have benefited a small fraction of the workforce.The counterpart of this is the continuing high share of labor still employed in agriculture characterized by anemic growth in productivity. The Lewis (1954)-style transformation of labor moving out of low-productivity agriculture in large quantities has still not happened in India, with adverse consequences for income distribution. In short, India’s path of specialization has been unusual: premature deindustrialization and precocious servicification, combined with weak agricultural productivity and a lack of reallocation of employment away from low- to high-productivity sectors. This path carries the risk that patterns of inequality will persist and may even worsen over time.

-Subramanian and Lamba, ‘Dynamism with Incommensurate Development (AEA)

2) Inter-state disparities:

As mentioned earlier, Kohli argues that the economic reforms in India were pro-business and not pro-market. Had it been pro-market then all the states would have seen a similar economic growth trajectory, not only the states that were pro-business. This pattern is reflected in the 2017-18 Economic Survey analysis. The states that had high per capita GDP and higher economic growth rate are the same since the economic reforms were kick-started. The authors have defined this phenomenon as ‘divergence’ when the well-off regions became more prosperous with time, while the worst-off states couldn’t catch-up. ‘Convergence’ happens when the economically poor regions grow faster than the well-off regions and they catch-up with time.

Between 1994 to 2004, while the provinces in China neither showed signs of convergence or divergence, Indian states started to diverge. The richer states became richer in the decade after the economic reforms.

From 2004 onwards, while the provinces in China started to converge (poorer provinces started catching-up with the richer provinces), in India, during the same time-period, divergence accelerated.

The richer states that were prosperous in the 1990s were the same in 2014, as the poorer states languished behind. The authors argue that the convergence never happened because of the governance traps and weak state capacity.

The striking contrast between the results in India versus those in China and internationally poses an important puzzle. If a state/country is capital-scarce and poor, then it seems as if returns to capital should be high and the area should be able to attract capital and technology, thereby raising its productivity and enabling catch-up with richer states/countries. Within India, where borders are porous, this process of convergence has failed. But across countries where borders are much thicker (because of restrictions on trade, capital, labor, and technology),convergence has occurred. That pattern is not easy to explain. One possible explanation is that convergence fails to occur because of traps relating to governance and state capacity. Poor governance could make the risk-adjusted returns on capital low, even in capital-scarce states. Moreover, greater labor mobility or exit from these areas, especially of the higher skilled, could further worsen governance, creating a vicious cycle. Another possible explanation relates back to India’s structural pattern of growth. If growth has been skill-intensive, there is no reason why labor productivity would necessarily be high in capital-scarce states. Unless the less developed regions are able to generate skills (in addition to good governance), convergence may not occur.

-Subramanian and Lamba, ‘Dynamism with Incommensurate Development (AEA)

The other aspects of incommensurate development will be discussed in the next dispatch.

For further reading:

1) Economic Survey of India-2017-18 (Chapter 2): https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/budget2017-2018/es2016-17/echap02.pdf

2) Economic Survey of India-2017-18 (Chapter 10): https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/budget2017-2018/es2016-17/echap10.pdf

3) Why is India a ‘Flailing State’?: https://pubheal.wordpress.com/2020/03/02/why-is-india-a-flailing-state/