Dispatch #44: Indian Bureaucracy- Weberian or Applebian?

In this dispatch we will look at ways to evaluate the effectiveness of bureaucracy and governance and will see what role does autonomy play

Whenever we talk about the Indian bureaucracy, two dominant narratives come to our minds. One is what Max Weber propounded- an organization that has clearly defined goals, competence, separation of management and the officials are subjected to strict discipline and control. The other dominant narrative is from Sir Humphrey Appleby, a fictional character from the British TV series Yes, Minister. Appleby is a senior bureaucrat in the British administration and his sole objective is to safeguard his interests and perpetuate red-tapism in the administration through the sheer power of obfuscation.

In order to evaluate the effectiveness of the Indian bureaucracy, we need a framework that goes beyond the two binaries as mentioned above.

In his classic paper titled ‘What is Governance?’Francis Fukuyama has suggested a framework based on the capacity and the autonomy of bureaucrats, that can help evaluate the performance of the government. Fukuyama argues that the conventional way of evaluating bureaucracies, especially in low and middle income countries, does not give us a true picture of its performance.

Before we delve deeper into the subject, first let’s get some basics right.

What is governance?

Fukuyama defines governance as ‘a government’s ability to make and enforce rules, and to deliver services, regardless of whether that government is democratic or not.’ This definition slightly debunks our conventional thinking about good governance and democracy. Theoretically, we know that good governance leads to better economic outcomes and hence helps in sustaining democracy. But Fukuyama argues that if good governance involves making and enforcing rules then a dictator’s ability to send and kill political opponents, on an industrial scale, will also be counted as good governance.

Therefore, in this conceptual framework the quality of governance is different from the ‘ends that governance is meant to fulfill’. Governance, according to Fukuyama, is about the performance of agents (bureaucrats) in carrying out the duties of political principals.

What is bureaucracy?

Weber described the modern bureaucracy as an organization that is not patrimonial but is a technically proficient organization, possessing specialized expertise, certainty, continuity, and unity. The broad characteristics of a bureaucracy, according to Weber are:

An organization where the people working (bureaucrats) are free and have to obey the authority

Clearly defined hierarchies, discipline and control

Core area of competence

Candidates selected on the basis of technical qualifications

They take rule-based decisions impartially and impersonally

Fixed financial incentives

A clearly defined career trajectory for bureaucrats

In order to implement any policy, bureaucracy is needed. A legislature or an executive can help design a policy and make laws. Adding finer details and rules to implement it is done by bureaucrats.

Fukuyama describes this as procedural measures to evaluate bureaucracies. However he finds this Weberian definition too constricted. He argues, ‘the idea of bureaucratic autonomy-the notion that bureaucrats themselves can shape goals and define tasks independently of the wishes of the principles- is not possible under the Weberian definition’.

Economist Avinash Dixit writes, “Social and economic policy in any modern society has many dimensions.No policymaker, whether an autocrat or a democratically chosen legislature or executive,can implement policies directly. The tasks of collecting the requisite information, enforcing the rules, collecting revenues and disbursing payments, initiating and supervising public projects, and so on must be delegated to people and organizations that have or can develop special skills in these matters. Therefore a bureaucracy for policy implementation is unavoidable.”

Why are bureaucracies inefficient, in general?

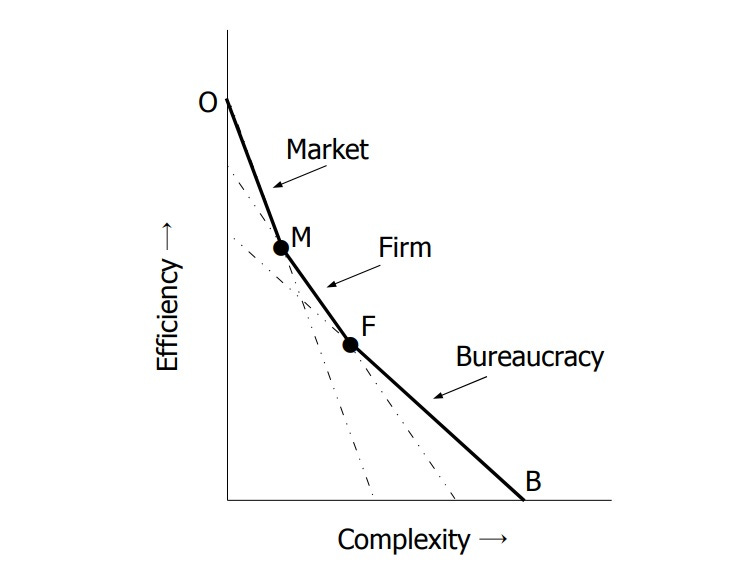

Dixit, in his paper titled ‘Bureaucracy, Its Reform and Development’ has tried to answer the question. He argues that because of multiple principals (political parties, departments, civil society organizations, private companies etc.) the complexity of the tasks, that the agents (bureaucrats) would undertake, has increased. Because of this increase in complexity, bureaucracy is less efficient.

A market and a firm is more efficient than a bureaucracy because the complexity of their tasks is lesser.

Such agencies must constantly negotiate with all their stakeholders to translate these vague goals into more precise operational ones. The need for administrators and operators to devote time and effort to such activities to maintain external relations adds to the agencies' costs of transaction and governance. No private firm would take on the burden of satisfying so many diverse and vocal stakeholders and still expect to operate profitably. In cases where a public service has a goal that can attract broad agreement, for example collecting garbage at a reasonable cost, the task can be outsourced to a private contractor. But many other essential public services and goods cannot be provided in this way. In other words, the high transaction costs of defining operational goals, and then the high governance costs of striving to meet them, help explain why certain activities fall to government bureaucracies in the first place.

-Avinash Dixit

How can we evaluate bureaucracy?

Fukuyama suggests four frameworks to evaluate a bureaucracy:

Procedural measures

Capacity measures

Output measures

Measures of bureaucratic autonomy

As we have seen earlier, there is a limitation to this approach of evaluating bureaucracy since it does not factor a bureaucrat’s autonomy and ability to take decisions independently.

The procedural measure does not have the enforcement power of a bureaucrat. One of the proxies for the enforcement power of any bureaucracy is its capacity to collect taxes. Successful collection of taxes provides resources to the government to further spend on public services or infrastructure. This enforcement power is what Fukuyama calls a capacity measure. However, capacity measure or enforcement capability is not enough to evaluate a bureaucracy. It should be able to provide public services to the citizens.

This ability of a bureaucracy to deliver services is called an output measure and is one of the approaches, according to Fukuyama, to evaluate the effectiveness of bureaucracy. This is one of the most conventional ways of measuring effectiveness. However, outputs such as health or learning outcomes cannot be simply attributed to bureaucratic action. There could be several other factors that would have to be considered. Fukuyama invokes Joel Midgal’s seminal work on weak states and strong societies, suggesting that the ability of the state to regulate a society depends on two factors- state capacity and society’s ability to self organize itself. A better organized society with its rigid structures can limit the penetration of a state and its bureaucracy. For instance the state is capable of distributing bicycles to girls so that their enrollment ratios in schools increase. But the state cannot ensure that more girls from the most marginalized groups are present in the same schools.

The final measure of evaluation is bureaucratic autonomy, which essentially means a bureaucrats ability to take decisions and make judgement calls. Samuel Huntington once claimed that a highly institutionalized political system has highly autonomous bureaucracy. The opposite nature of autonomy is subordination.

Autonomy properly speaking refers to the manner in which the political principal issues mandates to the bureaucrats who act as its agent. No bureaucracy has the authority to define its own mandates, regardless of whether the regime is democratic or authoritarian. Political principals often issue frequently overlapping and sometimes downright contradictory mandates. Indeed, there can be multiple principals in many political systems, that is, political authorities with equal legitimacy able to issue potentially contradictory mandates. Autonomy therefore is inversely related to the number and nature of the mandates issued by the principal. The fewer and more general the mandates, the greater autonomy the bureaucracy possesses. A completely autonomous bureaucracy gets no mandates at all but sets its own goals independently of the political principal. Conversely, a non-autonomous or subordinated bureaucracy is micromanaged by the principal, which establishes detailed rules that the agent must follow.

-Fukuyama

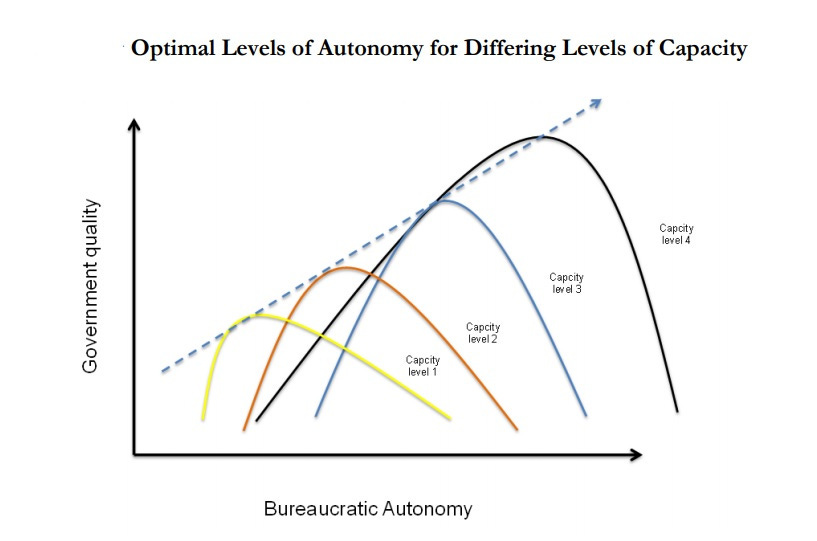

If we plot autonomy on X-axis and governance quality on Y-axis then the relationship between the two would look like an inverted U curve.

At the extreme left of the autonomy axis will be complete subordination or too many rules by the principal while at the other end of the axis we will have complete autonomy or discretion. For a bureaucracy that can deliver good governance neither subordination nor complete discretion is optimum. The peak of the U curve is where a bureaucracy can deliver good governance. The peak is also slightly shifted to the right, indicating that too much micromanagement is not beneficial and more autonomy within a bureaucratic set-up leads to innovation and out-of-box thinking.

There are myriad examples of excessive subordination leading to poor performance. One of the worst forms is when bureaucracies lose control over internal recruitment and promotion to the political authorities and are staffed entirely by political appointees. This is in effect what happens in clientelistic political systems. But even in the absence of clientelism, bureaucracies can be excessively slow-moving and indecisive because they are excessively rule-bound.

-Fukuyama

He further writes:

If an appropriate degree of bureaucratic autonomy is an important characteristic of high quality government, then neither the Weberian nor the principal-agent models can stand intact as frameworks for understanding how bureaucracies ought to work. The Weberian model, as noted earlier, assumes that bureaucrats are essentially rule-bound implementers of decisions made by political authorities; they may have technical capacity but they don't have the authority to set agendas independently. The principal-agent framework is inadequate as well because it too assumes that agents are simply tools of the principals, whereas in a good bureaucracy authority often flows in the reverse direction, from the agent to the principal.

-Fukuyama

Capacity and autonomy

The quality of governance and the effectiveness of bureaucracy can be evaluated from the interaction between capacity and autonomy. A bureaucracy with low capacity and low competency should have minimal discretion and their decisions should be rule bound. Hence in such a scenario, the U curve between autonomy and governance quality would be tilted towards the left. A bureaucracy with high capacity and professional competency can have relatively more autonomy. Hence in this scenario, the U curve between autonomy and governance quality would be tilted towards the right.

Another way of plotting the capacity and the autonomy for bureaucrats would like the figure given below:

One always wants to move up the Y-axis to higher capacity, particularly with regard to the professionalism of the public service. This however is not something that can be done easily, and it is not something that can in any case be accomplished in a short period of time. If a country cannot significantly upgrade capacity in the short run, one would want to shift the degree of autonomy toward the sloping line. This would mean moving towards the left in a low-capacity country, and toward the right in a high-capacity country.

-Fukuyama

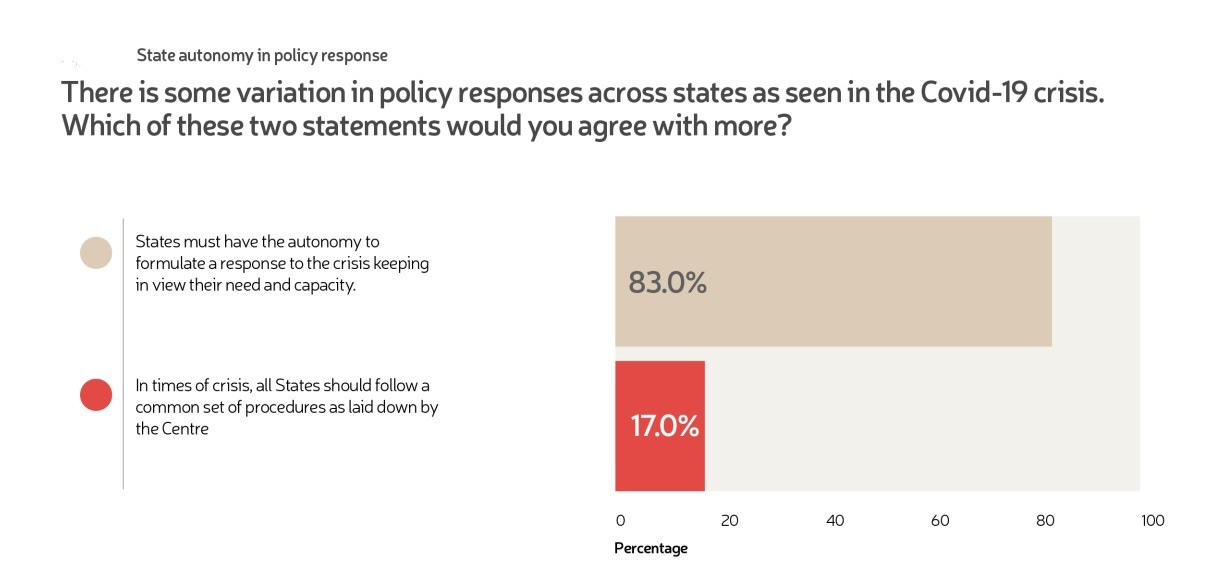

The primacy of autonomy given to bureaucrats is quite evident in Indian bureaucracy’s role in fighting the pandemic. At a time when decision making should have been dispersed in order to give autonomy to bureaucrats, the political authority was decentralised, thus weakening our strategy to fight the outbreak and its aftermath.

In a recent survey conducted by the Centre for Policy Research, several IAS officers indicated that the response to fight the crisis would have been better had there been more autonomy.