Dispatch #48: Public policy failure-Do we know enough?

In this dispatch we will discuss about public policy failures; how often do policies fail and will see if we know enough about policy failures

Recently, Puri became the first Indian city that would provide its citizens clean drinking water from a tap. This was achieved under Odisha government’s Sujal scheme.

The secret behind this success is meticulous planning, training and good implementation strategy.

A recent study shows that the Mid-Day Meal (MDM) Scheme has led to inter-generational nutrition benefits in India.

The success of these schemes indicates the success of the broad principles that guide the governments (both State and Union). These broad guiding principles that help the governments to take measures are called policies.

We often say that a policy was a success or a failure on the basis of the results yielded by that policy.

But what is a public policy failure?

How often do public policies fail?

Why do they fail? Poor design or poor implementation?

These are million dollar questions in public policy and international development. How often do public policies fail,actually depends upon how we define ‘failure’. They fail 25% of the time when ‘project or product success’ is measured and they fail 75% of the time when we broaden the definition of policy success to the actual impact of the policies and to what extent have they solved the problem for which they were designed in the first place.

This is the central argument of Harvard Kennedy School’s professor Matt Andrews, in his paper titled ‘Public Policy Failure: How often?and what is failure anyway?’

Why do public policies fail and why is it important to track the failures?

Andrews answers this question by saying:

Public policies are often needed to address society’s toughest issues—where the market has failed, for instance, or where societies face collective action challenges, or where public goods need to be produced. The world is in trouble if public policies targeting such issues fail routinely, and we should know if this is indeed the case. Public policy initiatives also absorb a large portion of the world’s resources— accounting for an estimated 16% of global gross domestic product in 2017,1 or $13 trillion—and a high rate of policy failure would mean that we are wasting these resources. We need to know if this is the case, to consider reallocating our limited resources.

-Matt Andrews

There are a few methods to assess the success or failure of a public policy, such as audit reports, cost-benefit analysis, citizen surveys etc., but they fall short in explaining ‘how often’ do policies fail.

Andrews, in this paper, has analysed around 400 public policy interventions, steered by the World Bank all around the world between 2016 and 2018, in order to understand the frequency of public policy failures. He concludes that failure happens between 25% to 50% of the time depending on how we define policy success and failure. The failure rate of any policy is 25% if the public policies were able to deliver on outputs, as per the process norms. This is also referred to as ‘project or product success’. However, failure happens 50% if the policy solves the problem that it was intended to solve and deliver on impact. This is also referred to as ‘problems solved, with development impact’.

Plan and Control public policy processes:

The governments are the main organizations that design and implement public policies. The executive branch of the government and the citizens act as agents and principles respectively.

Andrews adds:

At its simplest, public policy involves the many steps public organizations take to address problems raised by their constituents or members for attention. Policy interventions are made by an organization (or organizations) on behalf of the ‘public’ (or members), oriented toward a goal or desired state, such as the solution of a problem. These interventions are also typically part of an ongoing process without a clear beginning or end, since the challenges warranting policy attention—and the voices drawing attention to such challenges—are constantly changing.

-Matt Andrews

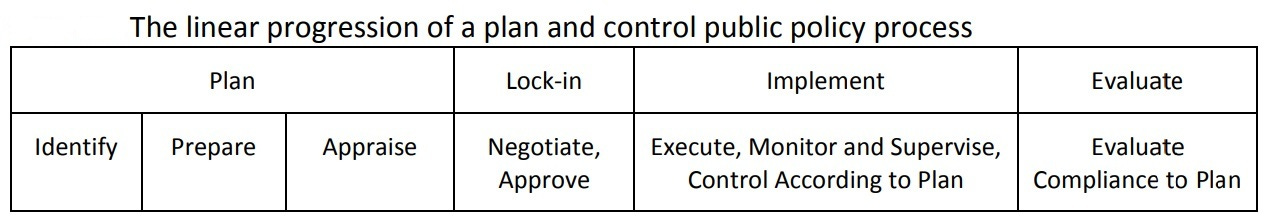

In the paper, Andrews has analysed around 400 public policies that the World Bank has implemented along with several governments. Most of these policies are implemented using a project lifecycle approach or project management approach. Institutions like the WB, bilateral institutions and governments often use this approach to implement policies. Some broad steps that are involved in this approach are- identification of problems, identification of solutions, planning, negotiation, implementation and evaluation. These processes follow a linear path which Andrews calls as ‘plan and control public policy processes’.

The ‘plan and control’ processes start typically with a detailed planning stage (the World Bank’s identification, preparation and appraisal steps), progress through a ‘lock-in’ moment where the plan is set in stone (the Bank’s negotiation and Board approval steps), move to the implementation stage where various agencies are given responsibilities to execute, control, and supervise activities (with the goal of ensuring that agents follow the plan), and culminate in an evaluation stage (where questions are asked about how well the execution complied with plans and produced promised deliverable)

-Matt Andrews

The WB has been rating these policy interventions according to these plan and control processes. The ratings, mainly cover three aspects of any policy implementation:

Efficiency: Whether the project adhered to the budget, timelines and other requirements

Efficacy: Whether the project’s objectives were achieved or not

Relevance: Whether the project’s activities are relevant enough to address the broad problems for which the project was designed in the first place

However, there is a problem with this type of rating.

This kind of World Bank project satisfaction rating does not directly assess whether policy interventions actually foster progress in addressing the broader development problems or needs that inspired project identification in the first place. Ratings merely suggest whether project deliverables are ‘relevant’ to these broader issues

-Matt Andrews

He further adds:

While “relevance” is one of the declared evaluation criteria, de facto evaluation practice suggests that the prime evaluation criterion for a project is whether it achieved its immediate objectives. Whether these are in turn relevant for achieving overarching development goals is often contestable and may in practice play a much lesser role. It would be cynical to believe that many projects do not make a difference for broader development goals – but the extent to which this is the case and varies across projects is not reliably reflected in project ratings

-Matt Andrews

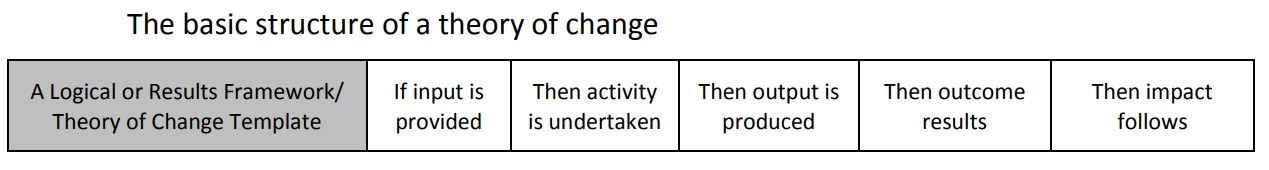

To foster the practice of thinking about the outcomes of projects and not restrict ourselves to the outputs and product delivery, the Theory of Change framework has started to gain relevance.

According to this approach, project designers must identify the logical ‘if-then-theory’ behind a policy intervention.The theory of change approach is intended to help project designers determine the scope of operational commitment, structure the operation, and communicate how the operation is (theoretically) expected to yield broader development impacts (and solve whatever problem the government is concerned about)

-Matt Andrews

How often do public policies fail?

As mentioned above, the WB ratings are done on the basis of project outputs, deliverables and products deployed to solve a policy problem rather than assessing whether the policy intervention solved the problem for which it was conceived. The project satisfaction rating system of the WB has rating systems ranging from 1 (highly unsatisfactory) to 6 (highly satisfactory).

According to this rating system, around 25% of the projects fall under the categories of highly unsatisfactory, unsatisfactory and moderately unsatisfactory. Three fourths of the policy interventions fall under satisfactory categories (moderately satisfactory, satisfactory and highly satisfactory).

A big proportion of the projects are able to deliver the outputs but fail to solve the policy problems and hence fall short of creating impact. The WB’s rating scheme, on satisfaction levels, is not sufficient to gather the impact levels.

The ‘project satisfaction rating’ only assesses what the Bank project intended to deliver in the initial project plan, and the efficiency of delivery (or extent of control in the execution process). It does not directly assess the development impact of the public policy intervention made through the project’s deliverables to solve whatever problem originally motivated the project, or if the project’s deliverables were used, or fostered real development. These ratings do not capture “whether the project made a difference for the client government’s performance, or ultimately, for development outcomes

-Matt Andrews

One of the solutions to this problem is to assess the ‘risks’ that the policy interventions face to achieve the development outcomes. Andrews looked at the project risk rating of the WB projects and concluded that a significant percentage (nearly 75%) of the interventions are under high risk, significant risk and moderate risk categories. This means three fourths of the projects won’t achieve the outcomes that would solve the policy problems.

The headline of a story about these ratings could quite easily read something like ‘51% of World Bank projects are at significant to high risk of failing to foster development outcomes’. This is quite a different message of public policy failure to that derived from ‘satisfaction’ ratings, where projects in the three most pessimistic categories (highly unsatisfactory, unsatisfactory, and moderately unsatisfactory) only account for 24% of the total portfolio

-Matt Andrews

He further argues:

So far, this analysis shows—at least in the context of the World Bank—that public policies do not fail 60% or 80% of the time. The failure rate is, rather, between 20% and 50%—depending on which of the World Bank’s assessment measures one focuses on. Which raises the question: which of the two measures should one focus on—satisfaction with immediate project performance or risk to producing or maintaining more demanding outcomes? The answer inside the World Bank is clear: satisfaction rates matter—not the risk to development outcomes.

The bias is perhaps best understood when considering how ‘plan and control’ interventions operate in context of the ‘theory of change’ discussed earlier. As introduced, theories of change used in project preparation and in budget proposals—especially those in the logical and results framework tradition—commonly specify the links between policy inputs and activities, activities and outputs, outputs and outcomes, and outcomes and impacts. The outcomes and impacts are arguably what governments and citizens want from policy interventions, but most projects execute this theory of change up to the output or initial outcomes stages only. The project deliverable is, therefore, defined at this stage—and the project commits to produce this deliverable

-Matt Andrews

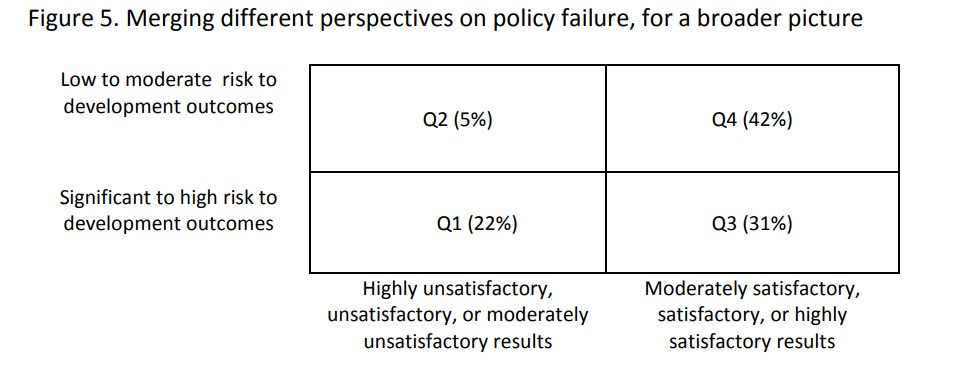

If we merge these two perspectives into a 2x2 matrix, then we will get a framework that gives us a broader picture of public policy successes and failures.

The fourth quadrant (Q4) is the most positive. It includes projects that were considered general to extreme successes in the ‘satisfaction’ rating (moderately unsatisfactory, unsatisfactory, or highly unsatisfactory) and were also seen as not risky in terms of the potential to deliver development outcomes (with low or modest risks to development outcomes). These projects—42% of the portfolio—were considered successes on both metrics. They should most please a public policy organization like the World Bank, which seems able deliver outputs, outcomes and impacts in the relevant project areas

-Matt Andrews

Andrews concludes:

This figure suggests a broader view on public policy success and failure that currently exists in the World Bank—or, I believe, in any organization working in a plan and control tradition that tends to foster a narrow ‘project and product success’ view. This new view suggests that only 41% of the World Bank’s policy interventions are both direct project and product successes and have the potential to foster indirect development outcomes and impacts. A larger portion of the organization’s policy portfolio—59%—is failing on either the direct ‘project and product’ performance measure or the indirect ‘problems are solved with development impact’ performance measure, or both.

This is a public policy failure rate that is surely ‘too often’; we need policies that more regularly solve problems, and that use resources more effectively in doing so. This raises a parting question: “What can be done to decrease the failure rate, and push more public policy interventions into Quadrant 4 of the figure above?

-Matt Andrews

Good Reads:

1) The power of school feeding programmes to improve nutrition:

“We hypothesize that women who received free meals when they were children in primary school would be better nourished and more educated as adults, and consequently would have children with improved height. To explore this hypothesis, we use MDM coverage data from the National Sample Survey – Consumer Expenditure Surveys (NSS-CES 1993, 1999, 2005), and child growth data from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4, 2016). We examine associations between historic MDM coverage and current child stunting, and explore potential pathways through which receiving a free meal in school may benefit future child growth”

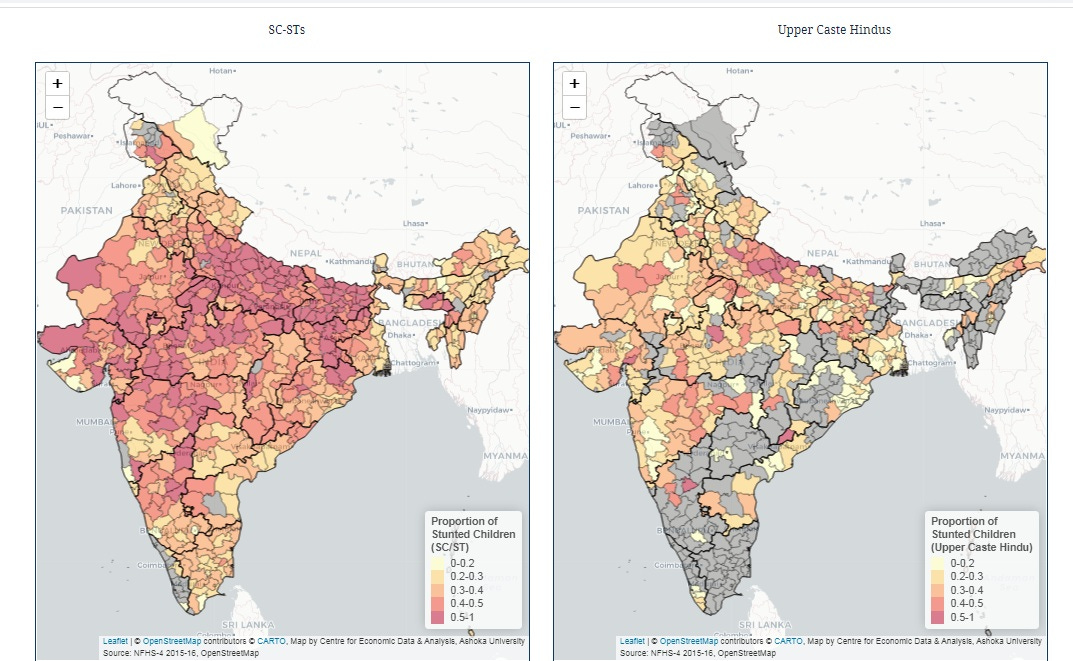

2) The Missing Piece of the Puzzle- Caste Discrimination and Stunting:

“The evidence shows that the illegal, but widespread, practice of untouchability is positively associated with height gaps between upper and lower-caste (Dalit) children. In particular, variation in the practice of untouchability does not affect the height of upper caste children, but higher spread of untouchability-related practices is associated with lower heights of Dalit children. The results moreover suggest a role for discriminatory practices in affecting service delivery to pregnant and nursing mothers from stigmatized groups and consequently the health outcomes of lower caste children”