Dispatch #5: India's 'precocious' development pathway-Part 2

In this series, we will be looking at the unusual development pathway that India took and its consequences on the overall socio-economic development

In the previous dispatch, we discussed the unusual development pathway which India adopted and some of the consequences of it. We talked about premature industrialisation and servicification of the Indian economy and inter-state disparities as some of the consequences of India’s ‘precocious’ development journey.

Before moving forward, I would like to point out at a recent EPW article where the researchers have also talked about the unusual ‘servicification’ of the Indian economy. They argue that the services sector got a boost because of the huge FDI inflows. They begin the paper by talking about the structural changes in the Indian economy. A structural change in any economy means the sectoral contribution to the GDP changes, reallocation of labour happens from low-productive sector to high-productive sector and economy shifts from low-productive activity (agriculture) to high-productive activity (manufacturing and services).

The authors have used a Structural Change Index (SCI) to argue that because the East Asian countries had an organic transition from agriculture, to manufacturing and then finally to services, the SCI for them has followed a completely opposite path when compared the SCI trajectory of India that by-passed the manufacturing.

The authors argue that the increase in the FDI inflows in the service sector could be the reason why services play a dominant role in the Indian economy.

The Indian economy is perceived to have undergone substantial structural change since 1991, but the annual economic structural change indices show that the change has been significantly less when compared to the other major Asian economies. The services sector has dominated both the economic structure and growth rates, but it has failed to contribute much in terms of structural change and, thereby, reap the benefits; India can still benefit from its structural changes. The growth of the services sector affects the growth of industry positively not only by historical performance but also by current innovations. Such innovations are engendered by policy changes, social and cultural effects, and the discovery of new resources, and these innovations must be considered in policy formation. Both the services and industry sectors influenced GDP growth positively and significantly, but the impact of services growth on the overall growth of the Indian economy exceeded that of industry growth, and it had a significant positive impact on industry and emerged as the predominant sector of the Indian economy.A feedback relationship between FDI and services growth is a tell-tale sign of the services sector’s dependency on the external factor—FDI. This dependency is quite dynamic and unpredictable. If the services sector has a strong external link and it is dependent on the external market, any disturbance or decline in the external market would adversely affect the services-led domestic economy.

-Swapnil Soni & M H Bala, ‘Growth and Structural Change in the Indian Economy- An Analysis of Pattern, Determinants, and Outcomes’, EPW

An article on Mint has a very interesting analysis of India’s growth story vis-a-vis South Korea’s. In 1961, the per capita incomes of India and South Korea were more or less the same (India= $85.4 & Korea=$93.8). In 2019, the per capita incomes of these two countries diverged a big-time (India=$2,104.1 & Korea=$31,762). This happened because of South Korea’s focus on labour-intensive manufacturing like plywood, woven cotton fabrics, clothing, footwear etc. that boosted the exports and created manufacturing jobs.

As Panagariya writes in Free Trade and Prosperity: “Most products whose exports grew rapidly during the 1960s were labour-intensive. These included plywood, woven cotton fabrics, clothing, footwear and wigs... In the later years it only intensified, with new, unexpected items such as wigs and human hair emerging as major exports." This expansion of labour-intensive exports led to the creation of jobs, which helped people move away from agriculture towards manufacturing jobs. This led to income levels rising and that created a demand for services. In the process, a large part of the economy was rapidly urbanized.

-Vivek Kaul, Mint

Now, back to the incommensurate development argument, from the previous dispatch. In addition to the servicification and inter-state disparities, India’s precocious development model also led to low-social mobility of historically disadvantaged social groups and gender-based discrimination.

Over the past 70 years, the Indian state may have been able to widen its terrain in the sense that it is present at all levels of service delivery but a) its presence is erratic b) it has not done a good job when it comes to the handling sticky issues like caste and gender. Devesh Kapur has also written about such failures of the Indian state. He argues that policy failures happened because of these societal failures that perpetuated because of the social hierarchies and cleavages.

In 2015, 88 percent of India’s population had access to electricity, a substantially higher percentage than the 66 percent that would be expected based on a simple cross-country correlation between electrification and GDP per capita. However, where behavioral changes on “sticky” social norms and preferences are required, India’s progress has been slower. For example, 39 percent of India’s population practiced open defecation in 2015, also a substantially higher percentage than the 14 percent that would be expected based on a simple correlation between this practice and GDP per capita. When it comes to issues related to women and children’s welfare, the Indian state has been less effective. India’s adverse sex ratio reflects society’s strong son preferences, and despite legal proscriptions, there have been meager improvements.

-Devesh Kapur, ‘Why Does the Indian State Both Fail and Succeed?’, AEA

The societal failure that led to policy failure has several manifestations. Subramanian and Lamba have discussed the gender-based discrimination and low-social mobility of vulnerable groups and minorities in their paper.

Gender-Based Discrimination:

India has shown remarkable progress in 14 out of 17 indicators, relating to agency, attitudes and outcomes, according to the Economic Survey of India-2017-18.

The progress is most notable in the agency women have in decision-making regarding, household purchases and visiting family and relatives. There has been a decline in the experience of physical and sexual violence. Education levels of women have improved dramatically but incommensurate with development. On 10 of 17 indicators, India has some distance to traverse to catch up with its cohort of countries. For example, women’s employment has declined over chronological time, and to a much greater extent, in development time. Another such area is in the use of female contraception: nearly 47 percent of women do not use any contraception, and of those who do, less than a third use female controlled reversible contraception. These outcomes can be disempowering, especially if they are the consequence of restrictions on reproductive agency. Whether women “choose” or acquiesce in their limited choices are important and deeper questions.

-Economic Survey of India, 2017-18, ‘Gender and Son Meta-Preference: Is Development Itself an Antidote?’

This table clearly indicates that India has done reasonably well in agency-related indicators like involvement in household decisions on health and household purchases, but performs terribly bad in attitude and outcome-related indicators such as women’s participation in labour and using reversible contraception, both curbing the freedom and agency in some way.

India’s Female Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) is one of the lowest in the world. FLFPR, which is defined as the share of working-age women who report either being employed or being available for work, is 23.3%. Just 9 countries- Egypt, Morocco, Somalia, Iran, Algeria, Jordan, Iraq, Syria and Yemen, have FLFPR less than India, according to a Mint analysis.

An analysis done by the Hindustan Times shows that the gender gap in Labour Force Participation Rate is huge and has not converged since the 1990s even after a sustained economic growth for three decades. While the women are absent in the labour workforce category, their percentage is high in unpaid domestic work category.

Researcher Madeline McKelway from the Stanford King Centre on Global Development, argues that the reason behind low FLFPR in India is due to the low bargaining power of the women in the household and inability to persuade their husbands who have great control over women’s participation in the labour. Madeline suggests that Indian women are not able to persuade their husbands because of lack of self-confidence.

Poor countries tend to have larger gender gaps in education, more tolerance of violence against women, less say for women in household decisions, and less freedom of choice for women than rich countries; India has especially low freedom of choice for women and a particularly male-skewed sex ratio at birth (Jayachandran 2015). Living in this sort of society could create a general sense of low self-confidence in women. This may keep women from persuading their husbands that they should work, perhaps making women hesitant to try to persuade, giving women lower assessments of their work ability to share with their husbands, or making women less convincing in general.

- Madeline McKelway,'Intra-household and intra-personal constraints to women’s employment in India

According to the NFHS-4, 46% of women, between the age of 15 to 49 years, do not use any type of contraception for family planning. This is lower than the NFHS-3 data which said that 44% of women do not use any contraception.

Gender-based discrimination is more acute when we look at the son-preference phenomenon in India. The skewed sex ratio because of the selective sex abortion and female foeticide made Amartya Sen conclude that India had 37 million ‘missing women’. Although the selective sex abortion has declined in India because of laws, the Sex Ration at Birth (SRB) still remains skewed in favour of boys.

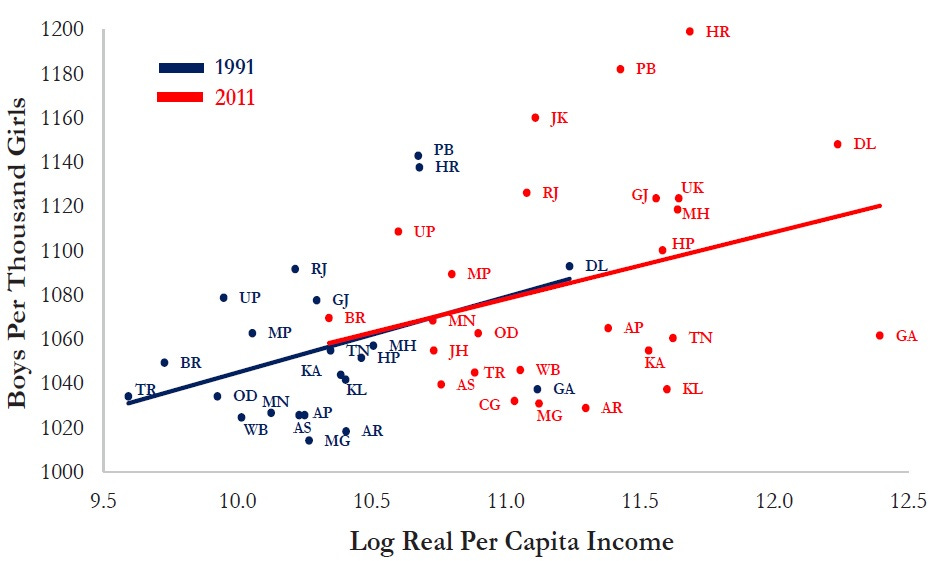

Even the developments levels in India and China did not prove to be an antidote to skewed sex ratio. There were more men than women in India and China in 2014 than in 1970. The fact that states having higher per capita income have more skewed SRB, proves the point that there is a negative correlation between income and sex-ratio.

The chart above gives a very interesting insight. Some of the high-income states like Punjab and Haryana have worsened their sex ratios between 1991 and 2011. Other high-income states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu have managed to have the ideal sex ratio of 1050 males for every 1000 females. This is because of other socio-cultural factors which we might discuss in a future dispatch. The 1994 Pre-Natal Diagnostics Technique (PNDT) Act, criminalised selective sex abortion in India. Still, the sex ratio in some states, as we have seen above, has worsened. The son preference has manifested in a very different manner over a few decades. Subramanian and Lamba call this the ‘son-meta preference’. This essentially means that the parents would keep having children until they get the desired number of sons. This son-meta preference has given rise to ‘unwanted girls’. The authors have estimated that India may have as many as 21 million unwanted girls.

When the child is not the last, the SRB is skewed towards girls, because the families tend to keep having children until they get the desired number of boys. In the process of having more boys, the families end up getting more girls (unwanted). Therefore in this case, when the child is not the last, the SRB hovers around the ideal number of 1.05. But, when the child is last, then this implies that the families would have got the desired number of sons and they would stop having children after that. Therefore, when the child is last, the SRB is higher than the ideal 1.05 because these last children are the desired number of sons that the families wanted.

As Seema Jayachandran argues, this son-preference has resulted in poor health and nutrition of Indian women since the families would have ‘higher human capital investments in males than females’. Research done by Annamaria Milazzo on the mortality and morbidity of Indian women proves that the women with the first-born girl are more likely to be anaemic and morbid. The son preferring fertility behaviour is forcing Indian women to reduce the birth-spacing, thus endangering their health and survival.

India’s gender-based discrimination in the workforce and skewed sex ratios proves the point made by Devesh Kapur that the Indian state has done a poor job in addressing societal failures because of shying away from the sticky issues like gender.

In the next dispatch, we will discuss how incommensurate development in India has resulted in low social mobility for the historically disadvantaged groups and minorities.

Good Reads:

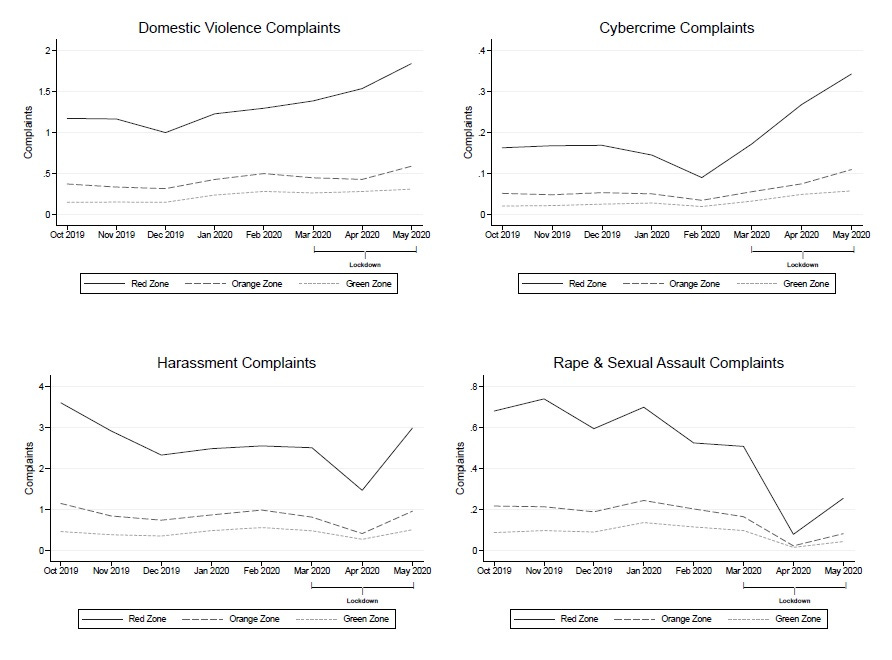

In the latest working paper, published in NBER, two UCLA researchers have argued that there’s a significant increase in violence against women during the COVID-19 lockdown in India. The study shows that the cases of cybercrime, harassment, rape and sexual assaults have increased during the lockdown, in the red-zone areas. This increase in the violence against women is attributed to the strict lockdown rules that restricted mobility. The researchers have used the data of the complaints received by the National Commission for Women during the lockdown.

In another interesting paper, economist Ashwini Deshpande has analysed the effects on gender gaps in employment and domestic work in India during the lockdown.

Deshpande has also written a brilliant article on the increase in domestic violence against Indian women during the lockdown.