Dispatch #50: The persistence of caste in India

In this dispatch we will look at how caste affects human development indicators and will probe whether the crimes against dalits is backlash against increase in mobility and consumption

In his 2010 book titled ‘The persistence of caste’, Anand Teltumbde has articulated the political economy of caste based atrocities in India quite well. Written after the infamous Khairlanji massacre in 2006, Teltumbde has busted several myths around the institution of caste and its persistence in the 21st century.

He argued that the project of modernity and its off-shoots such as globalization and economic liberalization has failed to contain caste based discrimination and violence. The idea that caste in India is not only the division of labor but actually the division of laborers has not disappeared completely.

India's caste question is shrouded in myths. Khairlanji effectively demolishes many of them. First, there is the neoliberal myth that globalization will eradicate caste. Although the experience of the majority of dalits is to the contrary, this myth is still upheld by a section of intellectuals, including some dalits, and continues to resonate occasionally in the print media and in academia. Then, we have the myth propagated by economists that the caste-based exploitation of dalits will wither away with their economic and associated cultural development.

-Anand Teltumbde

While we may disagree with Teltumbde’s assertion that the project of modernity has not done anything to improve our lives, the recent empirical evidence actually suggests that caste based discrimination has survived despite bouts of urbanization, progressive laws and opening of economy and has impacted human development indicators of the SC community in India.

By the way, don’t get me wrong. I am not one of those prophets of doom who is trying to delegitimize and blame modernity. Because by doing so we tend to give space to all the regressive forces that impede inquiry, liberty and progress.

Coming back to the empirical evidence.

In a recent study, Ashwini Deshpande (Ashoka University) and Rajesh Ramachandran (University of Heidelberg) have found that the prevalence of stunting (children under 5 years of age whose height relative to the age is low) is more in the SC-ST community in India as compared to other social groups. The height disadvantage faced by SC-ST children is higher than their counterparts from Sub-Saharan Africa and upper caste Hindu children.

They argue that the age-old question of ‘why Indian children are shorter than African children’ should be replaced with the question of ‘why are the gaps in child height between social groups within India so high’.

The regional variance in the prevalence of stunting is even more revealing. Using the data from the NFHS-4, they calculate that in nearly 51% Indian districts the stunting prevalence is 40% in the SC-ST social group.

In terms of regional patterns, a very clear pattern with the areas with the highest prevalence for SC-ST concentrated in the states of Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh, as can be seen by the northern and central plains being largely red in colour. More specifically, for the SC-ST children in the BIMARU region, in 195 or 84% of the districts the prevalence of stunting is greater than 40 percent; and in 105 or 44.49% of the districts more than half the children are stunted. The BIMARU region stands in stark contrast to the southern and northern regions; not only is the prevalence of such extreme levels of stunting lower across all caste groups but also the extent of differences across caste groups are much smaller. For the upper castes, in the BIMARU region, in only 38 percent of the districts the prevalence of stunting is greater than 40 percent. For the OBCs and upper caste Muslims, in the BIMARU region, the prevalence of stunting in 61 and 71 percent of the districts, respectively, is greater than 40 percent.

-Deshpande and Ramachandran

The authors conclude:

The gaps between Hindu UC and Dalit (SC) children is affected by societal discrimination, manifested in the illegal but widespread practice of untouchability. Dalit children’s height disadvantage increases in districts where the self-reported practice of untouchability is higher.

-Deshpande and Ramachandran

They further added:

The evidence shows that the illegal, but widespread, practice of untouchability is positively associated with height gaps between upper and lower-caste (Dalit) children. In particular, variation in the practice of untouchability does not affect the height of upper caste children, but higher spread of untouchability-related practices is associated with lower heights of Dalit children. The results moreover suggest a role for discriminatory practices in affecting service delivery to pregnant and nursing mothers from stigmatized groups and consequently the health outcomes of lower caste children.

-Deshpande and Ramachandran

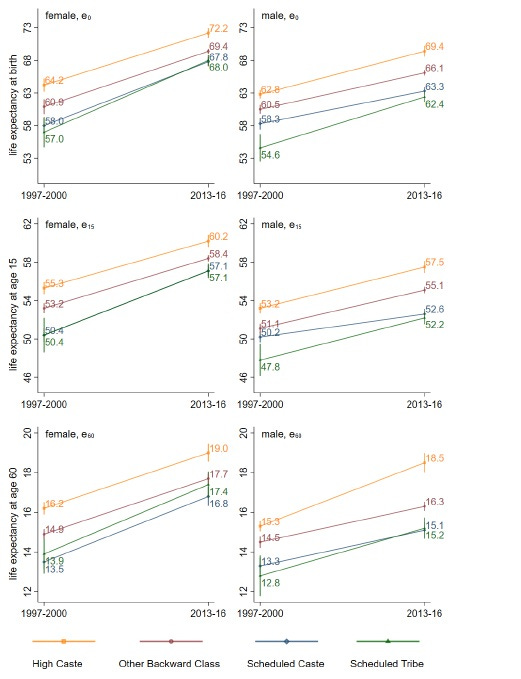

The fact that the accident of birth and your social group can determine how long you are going to live is very clearly articulated in this recent paper titled ‘Large and persistent life expectancy disparities among India’s social groups’ by Aashish Gupta (University of Pennsylvania) and Nikkil Sudharsanan (University of Heidelberg). They found large caste based differences in life expectancy among the 4 major social groups- SC, ST, OBC and High Caste.

They also found:

That the differences in life expectancy did not close between 1997-2000 and 2013-2016. Although absolute levels of life expectancy at birth, age 15, and age 60 improved for all groups, the differences between social groups persisted. For example, in 2013-2016,compared to the high castes, life expectancy at birth was still 4.4 years lower for women and 6.1 years lower for men from the Scheduled Castes, and 4.2 years lower for women and 7.0 years lower for men from the Scheduled Tribes. Most worryingly, absolute differences between Scheduled Caste men and High Caste men increased in this period.

-Gupta and Sudharsanan

They write:

More than sixty years ago, Dr. B R Ambedkar wrote that “the health of the Untouchable is the care of nobody. Indeed, the death of an Untouchable is regarded as a good riddance. Our findings reveal that these worries about the mortality and health of marginalized social groups in India are still pressing concerns in contemporary India. We find that Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes have substantially lower life expectancy than high castes and that these disparities have persisted over a nearly 20 year period between 1997 and 2016. Importantly, we also find that mortality disparities in India are not just a childhood phenomenon and are increasingly becoming an issue of disparities among older individuals.

-Gupta and Sudharsanan

Most of these disparities in the human development indicators are due to the caste based inequalities. In a recent paper titled ‘Caste inequality in Indian states’, Poulomi Chakrabarti (Queen’s University) has operationalized some of these inequalities. She has categorized equality in 3 ways-

Equality of outcomes: The proxy for this indicator is income equality among the social groups (BGI). The BGI ranges from 0 to 1. If the BGI is closer to 1 then that means there are wide disparities in income levels of the SC community with respect to others

Equality of opportunities: The proxy for this indicator is literacy rates among the social groups across all states

Equality in social status: The proxies for this indicator are levels of untouchability, inter-caste marriage and caste-based violence

From the figure above, the difference in the patterns of caste inequality between North and South India is quite evident.

Poulomi writes:

Regardless of the contrasting patterns in types of inequality, some states do present some consistent results. The most obvious difference is the North-South divide – as scholars of social movements predict, the southern states are indeed more equal when it comes to caste relations. The northern states of Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar have high levels of inequality on most measures. Assam and Kerala, in contrast, fare better than most states. Kerala’s exceptional performance in development and egalitarian social structure has been documented by a number of scholars. Caste politics in Assam has unfortunately attracted less scholarly attention but these findings seem consistent with existing research. It is the only state where the share of the non-agricultural workers employed in SC-owned firms is higher than their population share. Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, and West Bengal also generally rank low in many measures of caste inequality. Odisha, Karnataka and Jharkhand rank in the middle on most measures.

-Poulomi Chakrabarti

One very interesting observation in this study is that the districts where the violent crimes against the SCs are high are the same districts where the difference in the standard of living between the SCs and upper castes have declined the most.

Samuel Huntington had famously argued that conflict often accompanies social transformation. A recent study finds that violent crime against SCs is the highest in districts where the difference in the standard of living between SCs and upper castes has declined the most. Violence against SCs may hence reflect a backlash against lower-caste empowerment. Paradoxically, caste-based violence may be low in one of the two extreme contexts – when social relations are relatively egalitarian, as reflected in South India, or when the social order is so unequal that lower castes are unable to question their position in the hierarchy, as possibly reflected in some north Indian states. Data on crime are also likely to be affected by reporting bias. With the exception of serious crimes like murder, SC victims may be hesitant to report crimes, or the police may be reluctant to file reports due to pressure from local elites. The rate of SC murders in Kerala is low, but it has one of the highest levels of SC rapes. The data on rapes may in fact reflect lower reporting bias in gender-related crimes. Hence rather than indicating caste inequality, these numbers may in fact suggest relatively equal gender and caste relations, and a responsive State.. Rajasthan, in contrast, reports high levels of SC violence but the state arrests fewer people for these crimes compared to other states. It also ranks at the top of most measures of caste-based inequality.

-Poulomi Chakrabarti

This hypothesis of the backlash from the upper castes is rooted in the empirical evidence. According to the latest NCRB data, the number of crimes against SCs have increased in India in the past few years. In 2019 the number of cases registered under total crimes/atrocities against SCs have increased by 19% since 2015.

In her paper titled ‘Caste-based crimes and economic status: Evidence from India’, Smriti Sharma (Delhi School of Economics) has shown that an increased consumption expenditure ratio of SCs/STs in comparison to the upper caste leads to violent crimes by later against the former.

Theoretically, an increase in the expenditure ratio could lead to either a decrease or an increase in the incidence of caste-based crimes. It could lead to a decrease on account of various factors. An increase in the ratio of expenditures, by improving the relative economic position of SCSTs could result in an increased ability to defend themselves against physical harm by the upper castes by investing in better security measures. It could also lend them greater confidence to report crimes to the police thereby leading to a possible reduction in future crimes.Further, an improvement in their bargaining power could lead to the upper castes having greater respect for the low castes. Conversely,there could be an increase in the incidence of caste-based crimes as firstly, SC/STs could be perceived as more attractive targets for violence especially where the motivation is to extract some form of economic surplus. Secondly, they may be perceived as a threat to the established social, economic and political position of the upper castes.Thirdly,if an improvement in the expenditure ratio is on account of a worsening of the upper caste economic position,crimes could be used as a means of asserting their superiority and expressing their frustration at their worsened relative economic position. Therefore, which of these effects dominate constitutes an interesting empirical question.

-Smriti Sharma

The agrarian crisis in rural India, resulting in the stagnation of farm incomes has led to the decline of the middle caste groups who used to dominate over the SCs. In addition to this, the scramble for dalit votes by various political parties, both national and regional has aggravated the situation and has possibly led to the backlash from the erstwhile dominant castes.