Dispatch #51: The specter of ‘South Asian Enigma’

In this dispatch we will look at the malnutrition problem in India and will see why the average heights of Indian adults are decreasing while the average height in other countries are increasing

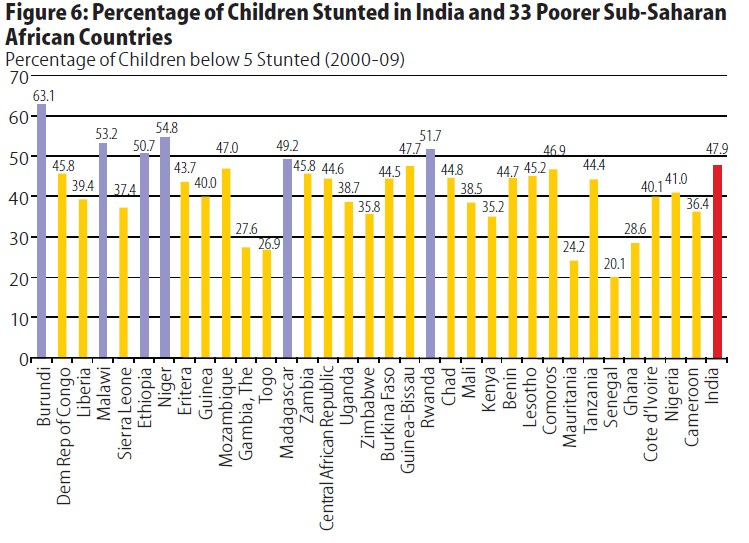

Child height is one of the best anthropometric measures of nutrition. Studies show that the average child born in South Asia is more likely to be stunted (low height for age) than a child born in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). These studies reveal higher levels of stunting in Indian children than in African countries like Chad, Senegal and Central African Republic where the infant and child mortality, maternal mortality, life expectancy and education levels are far lower than in India.

In 1996 Vulimiri Ramalingaswami wrote a commentary to explain this paradoxical phenomenon. He and his colleagues coined the term ‘South Asian Enigma’ to explain the higher rates of child malnutrition in South Asia than in sub-Saharan Africa. The South Asian Enigma essentially refers to a paradoxical situation where the prevalence of malnutrition in countries like India, Pakistan and Bangladesh is higher than that in SSA despite having higher per-capita incomes and low child mortality.

The factors responsible for the South Asian Enigma are:-

1) Status of women and low birth weight of the child: Low birth weight (LBW) is the best predictor of malnutrition. Children born with LBW are generally found to have poor growth, not only in infancy but throughout their childhood.

LBW indicates that the child was malnourished in the womb and that the mother did not get proper nutrition during her pregnancy. Therefore the proportion of children born with LBW clearly indicates the condition of women and their poor health and nutritional status.

In South Asia, specifically in India, the proportion of children born with LBW is quite high.

2) Disease due to poor sanitation: Frequent onslaught of disease, due to poor sanitation conditions, drain away the nutrients from the body in vomiting and diarrhea. This leads to the fall of nutritional reserves in the body and the growth starts faltering.

In India open defecation is widespread. Children who grow up in a high density population with no provisions of toilets and safe drinking water are more exposed to fecal pathogens which cause enteric or intestinal infections. This intestinal infection has a greater effect on height than on mortality.

3) Breastfeeding: Breast milk not only meets a child’s nutritional needs. It also protects against diseases because of its immunological properties. Breastfeeding is very essential for a child’s growth in early months of life.

A large proportion of children in India are deprived of exclusive breastfeeding( only mother’s milk should be put into the child's mouth) within a few hours of birth because of several factors, social and cultural factors being some of them.

In 2020, India ranked 94th out of 107 countries in the Global Hunger Index. Although the rank has improved in recent years, the level of hunger was in the ‘serious’ zone. The Global Hunger Index (GHI) scores are based on 3 dimensions of hunger- insufficient caloric intake (undernourishment), child undernutrition and child mortality. These three dimensions use the following four component indicators to measure a country’s GHI:

1) Undernourishment

2) Child wasting

3) Child stunting

4) Child mortality

In 2013, a major debate erupted between economists and public health scholars on the same issue. While on one side Arvind Panagariya dismissed the South Asian Enigma and argued that the higher prevalence of malnutrition in India vis-a-vis sub-Saharan Africa is due to genetics and a flawed measurement approach by the WHO, economists and scholars like Deaton, Dreze, Spears, Coffey, Seema Jayachandran and Rohini Pande highlighted other socio-economic factors and environmental factors that lead to high rates of stunting and malnutrition in India.

Panagariya began his arguments by claiming that the economic reforms have not only accelerated the growth but has also contributed in reducing the gap in poverty ratios between the most socially disadvantaged groups and others. By doing this he refuted the claim of the reform critics who claim that India’s growth story has done very little to address malnourishment in Indian children. His paper rejected the claim that India has over 40% malnourished children by questioning the current methodology of measuring malnourishment which uses common height and weight standards across the world to determine malnourishment without taking into account the differences in genetic,environmental, cultural and geographical factors.

He emphasized on the correct methodology of measuring malnourishment because of two fundamental reasons-

a) Proper measurement and determination will ensure proper allocation of scarce resources

b) An erroneous assessment would lead to a healthy child getting food supplements which would later lead to obesity and other health disorders.

Contrary to the current practice of measuring malnutrition, using height and weight of the children, Panagariya argued that malnutrition is a multidimensional phenomenon and should be divided into protein energy malnutrition and micronutrient deficiency. The manifestations of protein energy malnutrition are poor gains in height, weight and circumference of head and upper arm, skin peeling, sparse hair and liver enlargement.

Similarly micronutrient deficiency which occurs due the deficiency of iron, iodine and various vitamins, results in anaemia, bone deformities and night blindness. This multi-dimensional malnutrition can be only identified through a medical check-up. However, after the thrust of Millennium Development Goals, the pressure of measuring the proportions of children suffering from malnutrition, made the measurement of height and weight as the key determinants of malnutrition. The WHO further standardized this kind of measurement in 2006 after which the measurement of heights and weights became mandatory for the measurement of malnutrition. Panagariya claimed that this singular focus on height and weight is problematic as it ignores the multi-dimensionality of malnutrition.

Panagariya compared the life expectancy, infant mortality rate, maternal mortality rate, under-5 mortality rate, percentage of underweight and stunted children of 33 sub-Saharan African countries with that of India. He found that while in India the life expectancy is higher and the IMR, MMR, U5MR are lower than SSA, the prevalence of children stunting and underweight in India is higher than that of SSA.

The charts above clearly show the mismatch between the better health indicators of India as compared to Chad and Central African Republic, but at the same time worse stunting and under-weight percentages in case of India as compared to the other two countries. One reason for this pattern of health and nutrition indicators could be better health infrastructure in India as compared to African countries. However, Panagariya argued that this is the fundamental problem at the very outset that the methodology with which they are measured is flawed and this results in exaggeration of malnutrition in India even though other health indicators are better. He claimed that countries that have better health infrastructure also nourish their children better.

The contention lies in the measurement of the anthropometric indicators of malnutrition like stunting, underweight and wasting. Panagariya had focused on the determination of stunting. His first argument against the methodology was that the height of any individual may vary due to genetic reasons; hence it would be very difficult to conclude that whether the short height of the individual is due to malnourishment or due to genetic factors. His second argument against the prevalent methodology was that the comparison of height of an individual against the heights of the ‘reference population’ is completely flawed because this reference population is very limited in genetic, geographic, cultural and socio-economic variability.

Therefore comparing an Indian child with a Dutch child who is born in a different geographical location, with different socio-economic context and having an entirely different genetic disposition is meaningless. According to Panagariya the problem with this methodology was that it assumes that population of children of different race, ethnicity, culture, time period and geographical locations would have the same height provided they are given the same amount of nutrition. Therefore any difference in the heights of children, according to this assumption, would be attributed to malnutrition, without taking genetics and other factors into account.

He thought that there is a gradual ‘catch-up’ phenomenon which is under way. According to the ‘catch-up’ hypothesis it takes several generations of balanced diet for a country to match up to the heights and weights of that in other countries. Therefore comparing the Indian children who are still under the ‘catch-up’ phase with the healthiest population of children from other countries is counterproductive.

Deaton, Dreze, Spears and Coffey, in a strong rebuttal argued that it's not the genes or flawed methodology that keeps Indian children malnourished, but factors such as status of women, disease environment, sanitation and open defecation are reasons for high stunting prevalence in India.

On malnutrition and it’s larger implications, the authors write:

Stunting among Indian children matters: shorter children are disadvantaged.There is evidence from around the world that within population differences in height are strongly associated with within population differences in cognitive outcomes, productivity and health. Taller Indian children have better cognitive outcomes than shorter Indian children – along a much steeper height- cognition gradient than children in the US– which is exactly what we would expect from the literature on the harmfulness of early life malnutrition, whether it is caused by inadequate diets or a heavy burden of disease, or both.

-Deaton,Dreze, Spears and Coffey

Similarly Seema Jayachandran and Rohini Pande established that there is a nutrition gradient in Indian families. This essentially means that the nutrition levels decrease in an Indian household if thes second or subsequent child is a girl and keep on decreasing with subsequent child born since the family is not able to invest more resources in the nutrition.

In another important study, Diane Coffey argued that the deficits in maternal nutrition and low weight of women during pregnancy is associated with high levels of malnutrition in India. Similarly after surveying 112 districts in India, Dean Spears argued that poor sanitation and open defecation plays a major role in stunted growth of Indian children.

While one may say that most of the research on malnutrition in India is focussed on children, the recent study published in PLOS journal has highlighted stunted growth of Indian men and women. In the paper titled ‘Trends of adult height in India from 1998 to 2015’, researchers Krishna Kumar Choudhary, Sayan Das and Prachinkumar have investigated the trends in adult heights between 3 NFHS (i.e. between NFHS 2 and NFHS 4).

They conclude that while the average adult heights is increasing worldwide, the average adult heights, in the age groups of 15-25 and 26-50, in India has actually decreased.

The authors write:

In the context of an overall increase in average heights worldwide the decline in average height of adults in India is alarming and demands an urgent enquiry. The argument for different standards of height for the Indian population as different genetic groups needs further scrutiny. However, the trends from India clearly underline the need to examine the non-genetic factors also to understand the interplay of genetic, nutritional and other social and environmental determinants on height.

- Choudhary,Das and Prachinkumar

Some of the findings of the study are as follows:

1) Between NFHS 2 (1998-99) and NFHS 3 (2005-06), the mean height of the Indian women in the age group of 15-25 years increased marginally. However, between NFHS 3 (2005-06) and NFHS 4 (2015-16) the average height of the women in the same age group declined. Within the same age group the average heights of women from tribal groups and lower income quintiles have also declined.

2) Between NFHS 2 (1998-99) and NFHS 3 (2005-06), the mean height of the Indian women in the age group of 26-50 years improved significantly by 0.55 cm. Similarly, between NFHS 3 (2005-06) and NFHS 4 (2015-16) the average height of the women in the same age group improved by 0.13 cm.

The most alarming trends were found in men between both the age groups of 15-25 years and 26-50 years.

1) Between NFHS 3 (2005-06) and NFHS 4 (2015-16) the average height of men in the age group of 15-25 years has declined significantly by 1.10 cm. This decline was observed across all social groups and income quintiles.

2) Similarly, between NFHS 3 (2005-06) and NFHS 4 (2015-16) the average height of men in the age group of 26-50 years has declined significantly by 0.86 cm. This decline is also across all social and income groups.

The authors further write:

This decline in the average adult height of different groups among men and women is a matter of utmost concern and demands inquiry into non-genetic determinants of height, irrespective of the relative role of genetic factors in deciding height. Admittedly, the results may not present a completely coherent picture, but they compel us to further examine the role of social and economic factors in determining adult height. And while economic and nutritional status of Indian population is showing overall improvement, these trends in height also raise questions about equitable distribution of these benefits across the population.

- Choudhary,Das and Prachinkumar

In an interview for the Boom Live website, two public health researchers from the Public Health Foundation of India, spoke about how more than genetics it’s the nutrition that affects the heights of the Indian population.

Proper nutrition is an important environmental and social factor which determines optimal growth which in turns results in ideal height for age in children. The less than optimal gain in height due to lack of proper nutrition is called stunting. If the mother is undernourished or is herself growing (adolescent pregnancies) and has not reached her full potential height, her baby is at higher risk of being undernourished and nutritional insult for the baby may start from the womb itself. The population as a whole has inequalities in terms of nutritional intake. Several children are not receiving optimal nutrition and as a result do not grow up to their full potential. This compromise in nutrition shows stunted growth in several children which then adds up to poor adult height reflected in the population.

-Dr Suparna Ghosh Jerath

Trends in height take some time to change like we have seen in this paper. Essentially the point the paper is making is to reflect on the intergenerational impact or deprivation of other nutrients in their growing years. The initial stunting in their childhood perhaps or the opportunities they got at that time are reflecting in their heights currently. It is important that we target the modifiable predisposing factors that affect both nutrition and height and work on them so that these children can then go on to become healthier adults. The mother's education also plays a huge role in the nourishment provided to the child. It affects the child's height attained.

-Dr Shweta Khandelwal

The Covid-19 pandemic has worsened the situation with respect to child and maternal nutrition. In this study, the researchers have found out that due to economic and supply chain disruptions and collapse of health systems, the situation of child and maternal nutrition in low and middle income countries has deteriorated. The authors have urged the governments to make ‘nutrition a priority’.