Dispatch #52: The politics of healthcare in India

In this dispatch we will look at the political economy of healthcare in India and will try to explore why health never becomes an electoral issue

The Covid-19 pandemic exposed the weak capacity of India’s public health system. The result of the perennial neglect of the healthcare system was out there for us to see especially during the second wave when the country was gasping for breath.

In the past 12 months or so we have had 5 state assembly elections and this year we have the most important assembly elections- Uttar Pradesh. Was better healthcare mentioned in any of those election rallies? Was better public health services part of the larger electoral agenda of any party? The political parties used all kinds of strategies to divert attention and undermine democratic accountability. Uttar Pradesh will go into the polls in a few months and we can already see diversionary tactics being deployed everyday to distract the voters from the real issues such as crumbling healthcare in the state. Using communal issues to incite voters, using dog whistles to cherry pick one community and keeping the communal pot boiling with inconsequential issues is what is also known as ‘Everyday Communalism’.

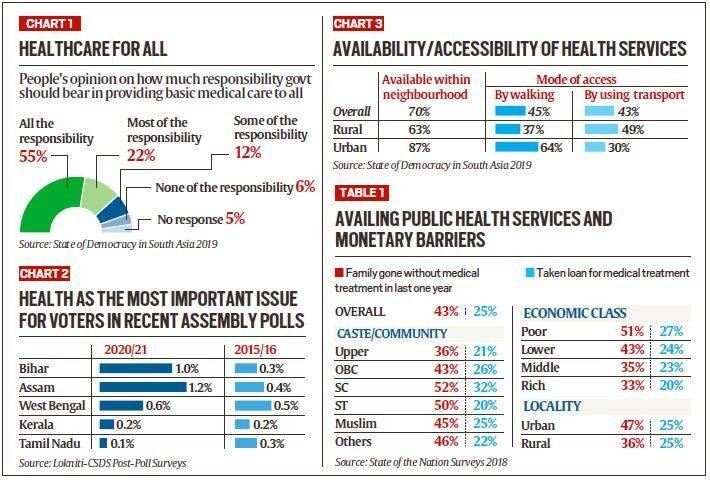

According to the State of Democracy in South Asia 2019 survey, 55% Indians believe that it’s the government’s responsibility to provide basic medical care to all. 22% and 12% believe that most of the responsibility and some of the responsibility of providing medical care rests with the government. Only 6% of Indians think otherwise. However, the Lokniti-CSDS post poll surveys indicate that health was not the top priority in the recent assembly elections.

Similarly, according to ADR’s ‘All India Survey on Governance Issues and Voting Behaviour 2018’ there is a huge gap between voters’ priorities on specific governance issues and the government’s performance on those issues. Out of the top ten governance issues, better healthcare came second as voters’ priorities, after better employment opportunities. But the score given by the voters on the government’s performance on providing better healthcare was below average (2.35).

In 2004, two World Bank economists, Stuti Khemani and Philip Keefer tried to explain as to why do the poor in India get poor services and why don’t they penalise the political parties for not providing basic services like healthcare. They argued that broadly there are three reasons that explain inadequate and poor-quality public services in India- focus on narrowly targeted goods to interest groups (club goods), lack of credibility of political promises to provide public goods rather than the targeted transfer of goods and social fragmentation.

Oxford University scholar, Tanushree Goyal, in her paper titled ‘Do citizens enforce accountability for public goods provision? Evidence from India’s rural roads program’ writes that the Indian voters do not necessarily vote on development issues or public goods provisioning. Her study is around the flagship Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (PMGSY) that provides all-weather roads to the villages in India. Even though the rural roads have made access to the markets and basic services like schools and health centres easy, the voters do not reward the incumbent governments. Voters respond to the caste affiliations rather than rewarding the political actors on the basis of public provisioning.

The findings have important implications for democratic governance amongst other debates. With the rise in infrastructure provision in many countries in Africa, these findings should worry scholars of democratic governance. Electoral incentives, generated through accountability mechanisms, are posited as a key means of improving service delivery in developing democracies. However, if voters remain unresponsive to policy provision, electoral incentives for public goods provision or improving service delivery, may diminish over time, leading to abandonment or poorer implementation of these crucial programmes.

There are several factors that have contributed to the de-prioritisation of healthcare in India.

First and foremost is the mass exodus of the Indian middle class from the public services. While Pratap Bhanu Mehta has coined the phrase ‘the biggest secession of Indian middle class’, Shankkar Aiyar calls this phenomenon the ‘Gated Republic’. Both Mehta and Aiyar draw their ideas from Albert Hirshman’s Exit, Voice and Loyalty. One equation that can summarise the great exit from India’s public health system is this:

Perennial neglect of public health -> Low quality of care -> Decline of trust in public health institutions-> Exit from public institutions-> Dependence on private sector-> Increase in out-of-pocket expenditure

The data from the 75th round of NSS clearly indicate the increase of dependence on private hospitals and care providers at the expense of public health institutions.

In the introductory chapter of his book The Gated Republic- India’s Public Policy Failures and Private Solutions, Shankkar Aiyar writes:

The choice before India’s denizen is to grieve, grate and grimace, or get out. In his seminal tome Exit, Voice, and Loyalty , Albert O.Hirschman points out, ‘Once this avoidance mechanism for dealing with disputes or venting dissatisfaction is readily available, the contribution of voice – that is, of the political process – to such matters is likely to be and remain limited.’ The voice of the average Indian is not heard and the wait has been too long. And so Indians are desperately seceding, as soon as their income allows, from dependence on government for the most basic of services – water, health, education, security, power – and are investing in the pay-and-plug economy.

-Shankkar Aiyar

Another major factor that has resulted in the neglect of broad based public health provisioning is the fact that the Indian state focuses on giving targeted private goods (example toilets) rather than broad based public services (example public sanitation infrastructure). Economist Arvind Subramanain calls this the ‘New Welfarism’ where the focus is on providing private goods to a target group- such as cooking gas (Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana), toilets (Swachh Bharat Mission), bank accounts (Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana) and electricity (Pradhan Mantri Sahaj Bijli Har Ghar Yojana- Saubhagya). These private goods are relatively easy to deliver, easy to monitor and are tangible.

Subramanian writes:

The New Welfarism of the Narendra Modi government represents a very distinctive approach to redistribution and inclusion. It does not prioritize the supply of public goods such as basic health and primary education as governments have done around the world historically; it is also somewhat ambivalent about strengthening the safety net which past Indian governments have pursued with mixed success. Instead, it has entailed the subsidized public provision of essential goods and services, normally provided by the private sector, such as bank accounts, cooking gas, toilets, electricity, housing, and more recently water and also plain cash.

-Arvind Subramanian

The government’s single minded focus on delivering these private goods can be assessed by reading the Economic Survey of India 2021 in which one full chapter was dedicated to the coverage of these goods. The survey calculated the Bare Necessities Index (BNI) by assessing the coverage of housing, water, sanitation, electricity and clean cooking fuel. The survey claimed that between 2012 and 2018, the coverage of bare necessities has increased dramatically in India.

While the bare necessities goods might have a positive impact, the focus on other pressing or infact ‘sticky’ issues has got diluted. Subramanian argues that during the same time period in which the coverage of basic necessities has improved significantly, child malnutrition in India has also increased. For him this is a story of retrogression and not of progress. The ‘New Welfarism’, as he calls it, means using public funds to provide private goods to the citizens as basic needs, while withdrawing focus on distributing public goods widely. The New Welfarism approach not only consists of conviction but also of calculation. Conviction of providing goods and services in order to improve the living conditions of the recipients; calculation of providing tangible private goods that can be measured and can later be benefited for electoral purposes.

He adds:

The New Welfarism embodies a vision, both imbued with conviction and laden with calculation. The conviction is that providing these goods and services will make a critical difference to the lives of the poor. Indeed, New Welfarism recalls the Basic Needs approach to development that was in intellectual vogue several decades ago. The conviction also stems from a belief that the power of technology can be harnessed to achieve successful implementation. New Welfarism’s calculation is that there is a rich electoral opportunity in providing tangible goods and services, which are relatively straightforward to deliver, measure, and monitor. Traditional government services such as primary education are intangible, which are difficult even to define, much less measure. But when the government promises toilets, for example, everyone can monitor progress. Either a toilet has been installed, or it has not.

-Arvind Subramanian

A similar point was made by demographer Monica Dasgupta in her paper ‘Public Health in India: Dangerous Neglect”. She argued that the success of public health services is negative in nature- an outbreak averted or a plague controlled are not ‘politically attractive’ choices as compared to infrastructure development which is tangible and measurable. For example toilet construction, a visible output, becomes central to the sanitation policy while ignoring sticky issues like usage of toilets, behavioural change, size of the pit, disposal of the waste and the plight of sanitation workers.

Another factor that has resulted in India paying less attention to healthcare and especially the quality of health services in public hospitals is ‘thin’ and ‘thick’ accountability. This idea was given by Lant Pritchett. Thin accountability comprises measures that can be easily measured and are judicable such as doctors absenteeism, health infrastructure, number of Primary Health Centers running as per the IPHS guidelines, number of institutional births, patient footfall etc. Thick accountability are measures that are not objectively measured and are not judicable such as the quality of care, patient satisfaction etc. The Indian state has been able to do reasonably well on ensuring thin accountability, but it has a long way to go to fulfill thick accountability.

This brings me to the last factor, which is the way the Indian state broadly works. There was a marked difference in the way the Indian state responded to the second wave of Covid-19 in April and May this year when compared to the reasonably better vaccination strategy afterwards. Although the vaccination policy also bungled in its early days. This clearly validates what Devesh Kapur has argued in his paper ‘Why does the Indian state both fail and succeed?’ The Indian state is very good at doing things on a mission mode such as Kumbh, elections, Census etc. However, it does not perform optimally while doing quotidian activities on a day to day basis such as providing good healthcare services, education or sanitation. According to Kapur, the Indian state is good at doing certain things while under-performing in other critical areas because it can perform well while doing episodic activities. This feature is quite common in all weak capacity states since to address an issue the state will muster all the resources for once and will go ahead to perform the task and will retreat once the task is finished.

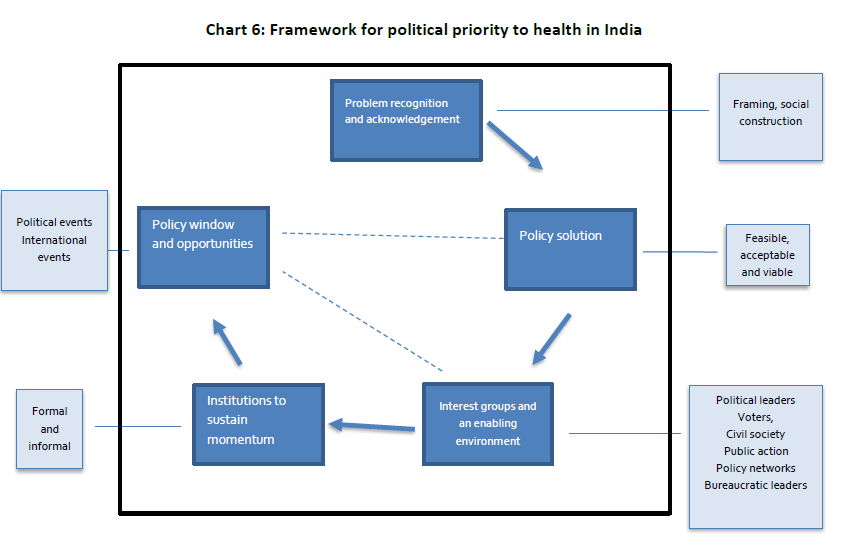

In their latest paper titled ‘The political pathway to health system improvements in India’, Sandhya Venkateswarana, Shruti Slaria and Nachiket Mor have introduced a framework that can ensure political commitment to better healthcare in India. They have identified five elements through which healthcare systems in India can get more political commitment through policy changes or increase in spending-

1) Recognition of the problem and acknowledging that it’s a problem that needs a sustainable solution

2) Policy solutions that have the potential to solve the problem

3) Interest groups such as civil society organizations, political leaders, voters etc. that can promote or endorse policy changes

4) Formal and informal institutions that can sustain policy changes

5) Policy window that provides political opportunity to introduce policy changes

The authors conclude:

While India has certainly witnessed some key social policy successes, arguably, political attention is often directed at short term clientelist strategies for electoral gains, or at areas that do not require system change (such as the building of toilets). Social policy successes are a function of the capacity of the system to deliver; where such capacity is weak, committing to social policy delivery runs the risk of unfulfilled promises. Focusing on short term clientelist approaches in such a case, may seem a more pragmatic approach electorally. However, such reliance in turn undermines the capacity of the bureaucracy to deliver public goods in an impartial, accountable fashion, creating a vicious cycle. The motivation to prioritise social policy is therefore strongly linked with the strength of delivery institutions, and where such institutions deliver effective services, the relationship between citizens and politicians is less driven by clientelist approaches. This has been observed in states such as Tamil Nadu, where stronger state capacity has resulted in a political focus (across political parties) on the delivery of social services.

- Sandhya and others