Dispatch #53: The unique connection between democracy,governance and healthcare

In this dispatch we will engage with the emerging literature of the quality of democracy and health care. We will also look at the governance aspect of public service delivery in India

Last year, in one of the dispatches, I reviewed academic literature that draws a correlation between democracy and economic growth. Subramanian and Lamba show how India defied the ‘modernization hypothesis’ and became democratic before attaining economic growth. They reiterated what Ashutosh Varshney argued in his 1998 article by describing India as a puzzle for most standard theories of democracy. Talking about Indian democracy and its development journey, Devesh Kapur talks about how redistribution took precedence over provision of public goods in India.

Kapur writes:

When countries pursue democracy prior to economic development, the democratic institutions adopted enhance the re-distributive powers of the state. For related reasons, precocious democracy contributes to weak public good provision. Being a “premature” democracy appears to have reduced India’s ability to raise revenues compared with other democracies, further undermining its fiscal ability to finance public goods. By not providing public goods before shifting to redistribution, the Indian state weakened the legitimacy and trust to create a virtuous circle that could strengthen the social contract between citizens and the state.

-Devesh Kapur

In their seminal paper, Acemoglu, Robinson, Suresh Naidu and Pascual Restrepo argue that countries who have switched from non-democracies to democracies achieve about 20% higher GDP (Gross Domestic Product) per capita in the long run (or roughly in the next 30 years). Elias Papaioannou and Gregorios Siourounis have also shown that when countries transition from a non-democracy to democracy then the per capita GDP growth increases.

While most of the literature focuses on the association between democratic institutions and economic growth, there is an emerging body of literature that draws correlation between the quality of democracy and the healthcare system of that country. In a recent study titled ‘Democracies linked to greater Universal Health Coverage compared with autocracies, even in economic recession’, Thomas Bollyky and others have argued that democracy is positively associated with universal health coverage and higher healthcare spending, even during economic recessions, for low income countries.

The study has three main findings.

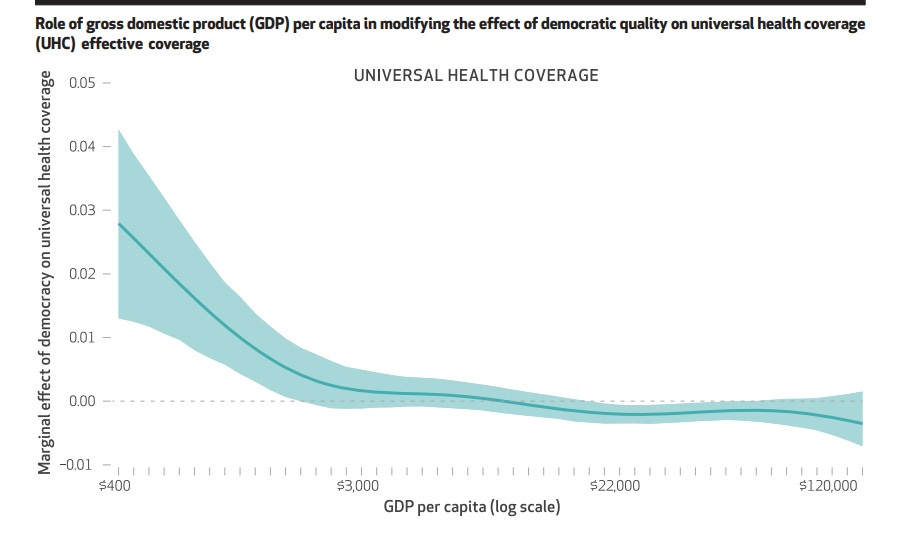

Firstly, the GDP per capita and democratic quality has a statistically significant and positive relationship with Universal Health Coverage (UHC). In other words, this means that the GDP per capita impacts democratic quality and UHC differently for different countries. The low income countries have a very significant and positive association between the quality of democracy and UHC that the government provides.

Bollyky and others argue:

The average low income country doubled its democratic quality from 0.04 in 1990 to 0.08 in 2019;we estimate that this increase was associated with a universal health coverage increase of 2.1 percent, holding constant country-specific time invariant factors, yearly shocks, probability of mortality due to war and terrorism, urbanization, and per person development assistance for health. For wealthier countries, with GDP per capita greater than $9,712, the association between democratic quality and universal health coverage was not statistically significant.

-Bollyky and others

Secondly, during economic recessions, the probability of reducing UHC coverage is higher in autocracies than in democracies. In a democratic set-up the government is accountable for delivering public services to the citizens.

The authors write:

Autocracies that experienced an economic recession increased universal health coverage by 1.95 percent less, on average, after five years than we estimate would have occurred in the absence of economic recession. In contrast, democracies that experienced economic recession increased universal health coverage by 2.08 percent more, on average, after five years than we estimate would have occurred in the absence of those shocks.

-Thomas Bollyky

Finally, they found that democracies tend to spend more on healthcare than autocracies.

This is not the first time when Thomas Bolyky has argued that democracies are good for health care and health outcomes. In a 2019 piece, he and his co-authors made a case that democracies can tackle the problem of non-communicable diseases better than autocracies.

However, India’s poor performance in providing good quality health care to its citizens, without major financial risks, is a clear departure from the hypothesis suggested by Bolyky and others. In my previous dispatch I wrote about the low demand of a good healthcare system and its politics in India. If there is one missing piece in health care services and the political economy puzzle, then that is governance. In her 2017 paper titled ‘Governance and public service delivery in India’, Farzana Afridi has written about how bad governance in India has impacted public services like health care. According to her three factors determine the governance of public service delivery:

Incentives (monetary and non-monetary) to public servants who act as agents to deliver public services for the principals (citizens)

Information to the citizens about the public services, quality of public services and how to access them

Weak state capacity that impedes the effective delivery of public services like health care

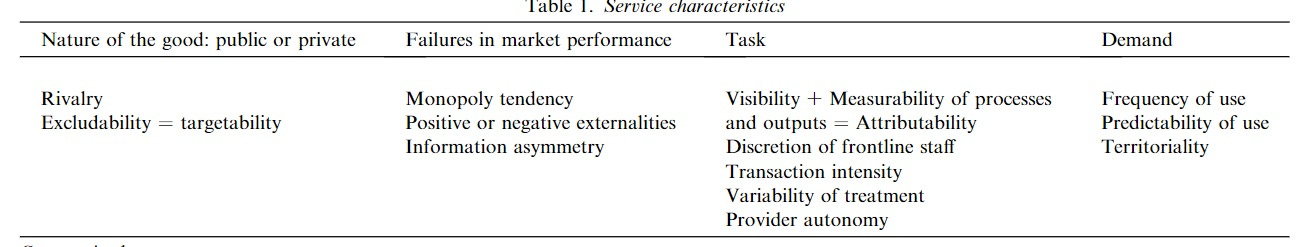

Richard Batley and Claire Mcloughlin, in their brilliant paper titled ‘The politics of public services: A service characteristics approach’, have offered a framework for understanding how the nature of public services determine its supply and effectiveness.

They argue that the government will show more interest in providing services that provide private goods (rivalry and excludability) since targeting becomes easy; services that have high visibility, measurability and hence high rate of attributability and finally, services that have predictability of use and territoriality since again it is easy to target them.

The question then arises as to how can the governance be reformed that can improve public service delivery in India.

The book ‘Reinventing public service delivery in India, edited by Vikram Chand,’ offers 7 key instruments that can be used to improve governance and public service delivery:

Promoting competition: More competition can improve service delivery by dismantling the monopoly and letting other players enter the space. Dismantling the Department of Telecommunications (DoT) and subsequent telecom reforms that increased teledensity and made calls cheaper is a prime example of promoting competition.

Simplifying transactions: This comprises improving service delivery through e-governance. This simplifies the transactions between the state and citizens.Andhra Pradesh’s E Seva has simplified transactions between the government and the citizens using e-governance.

Restructuring agency processes: While simplifying transactions is changing the way citizens interact with the government, restructuring agency processes is more complex. This involves restructuring the way the government agencies are performing their tasks and setting up new processes, monitoring mechanisms, reporting structures and transparency. Jonathan Caseley has documented the transformation of Maharashtra’s Registration Department which included consultations with the staff, reorganization of the registration offices that improved coordination and computerization.

Reinforcing provider autonomy: In India’s clientelistic politics, the government is both policy maker and service provider. This reinforces clientelism and hence focused delivery of private goods and services. This has led to corruption, rent seeking and politicization of public services. MP’s Rogi Kalyan Samitis (RKS) were one such mechanism where autonomous societies managed public hospitals and can levy user fees that can be spent on maintenance and buying equipment. This streamlined the procurement process.

Fostering community participation and decentralization: This ensures community buy-in and also makes them a critical stakeholder in ensuring that they get good quality public services. Rajasthan’s Lok Jumbish programme promoted community mobilization which resulted in transformation of the public education system in the state.

Building political support for program delivery: States like Tamil Nadu and Kerala that have a history of social mobilisations have created political support for program delivery and human development investments, no matter which ruling dispensation forms the government. Prerna Singh calls this as the solidarity effect.

Strengthening accountability mechanisms: Providing information about the coverage, performance and quality of public services is extremely critical to empower citizens. Abhijeet Banerjee has written about how information, in the form of report cards, about the performance of representatives and public services can have an impact on voters’ behavior.