Dispatch #55: 25 questions that every ‘policy wonk’ should ask

In this dispatch we will explore how policy makers can extract maximum and good quality knowledge before policy planning and implementation

Harvard Kennedy School’s Matt Andrews is one of my favourite public policy thinkers and scholars.His work on policy implementation and state capacity is quite influential. I intend to run a series on state capacity sometime, but that’s a different discussion.

A few months ago I unpacked his 2018 paper on public policy failures and successes. In the paper Andrews answered one simple question, how often do policies fail? And can we do something to avert the failure.

Just a quick recap of his paper.

We often say that a policy was a success or a failure on the basis of the results yielded by that policy.

But what is a public policy failure?

How often do public policies fail?

Why do they fail? Poor design or poor implementation?

These are million dollar questions in public policy and international development. How often do public policies fail,actually depends upon how we define ‘failure’. They fail 25% of the time when ‘project or product success’ is measured and they fail 75% of the time when we broaden the definition of policy success to the actual impact of the policies and to what extent have they solved the problem for which they were designed in the first place.

This is the central argument of Harvard Kennedy School’s professor Matt Andrews, in his paper titled ‘Public Policy Failure: How often?and what is failure anyway?’

Why do public policies fail and why is it important to track the failures?

Andrews probes the situation with this explanation:

Public policies are often needed to address society’s toughest issues—where the market has failed, for instance, or where societies face collective action challenges, or where public goods need to be produced. The world is in trouble if public policies targeting such issues fail routinely, and we should know if this is indeed the case. Public policy initiatives also absorb a large portion of the world’s resources— accounting for an estimated 16% of global gross domestic product in 2017,1 or $13 trillion—and a high rate of policy failure would mean that we are wasting these resources. We need to know if this is the case, to consider reallocating our limited resources.

-Matt Andrews

Andrews, in the paper, has analysed around 400 public policy interventions, steered by the World Bank all around the world between 2016 and 2018, in order to understand the frequency of public policy failures. He concludes that failure happens between 25% to 50% of the time depending on how we define policy success and failure. The failure rate of any policy is 25% if the public policies were able to deliver on outputs, as per the process norms. This is also referred to as ‘project or product success’. However, failure happens 50% if the policy solves the problem that it was intended to solve and deliver on impact. This is also referred to as ‘problems solved, with development impact’.

Plan and control public policy processes:

The government is the main organization that designs and implements public policies. The executive branch of the government and the citizens act as agents and principles respectively.

Andrews adds:

At its simplest, public policy involves the many steps public organizations take to address problems raised by their constituents or members for attention. Policy interventions are made by an organization (or organizations) on behalf of the ‘public’ (or members), oriented toward a goal or desired state, such as the solution of a problem. These interventions are also typically part of an ongoing process without a clear beginning or end, since the challenges warranting policy attention—and the voices drawing attention to such challenges—are constantly changing.

-Matt Andrews

As mentioned earlier, Andrews analysed around 400 public policies that the World Bank has implemented along with several governments across the world. Most of these policies are implemented using a project life cycle approach or project management approach. Institutions like the World Bank, bilateral institutions and governments often use this approach to implement policies. Some broad steps that are involved in this approach are- identification of problems, identification of solutions, planning, negotiation, implementation and evaluation. These processes follow a linear path which Andrews calls as ‘plan and control public policy processes’.

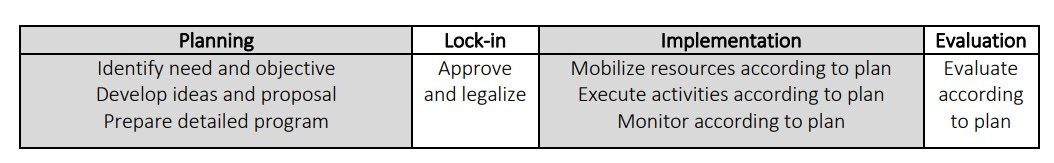

The plan and control process essentially has 3 parts:

Planning: involves identifying problem, planning and objectives of the interventions

Implementation: involves executing activities according to the plan and monitoring

Lock-in: lies between planning and implementation. It broadly includes approvals and legal aspects

The lock-in step actually limits further knowledge gathering, since the policy has already been firmed up and is ready to be executed. Therefore, it’s the planning phase where most knowledge gathering about the problem and sense making happens.

One of the ways to gather as much information as possible, by policy makers, in the planning phase is to use Log FrameWork (LFW). It helps to identify the ‘inputs’, ‘outputs’, ‘outcomes’ and ‘impact’.

In a recent paper titled ‘Getting real about unknowns in complex policy work’, Matt Andrews claims that LFW is quite popular among the policy makers across the world. One of the criticisms of LFW has been that in any policy, the connection between the outcomes, outputs and the inputs is not that straightforward, especially in complex systems.

A tool that can address this problem is the Theory of Change (TOC) tool. The TOC also helps policy makers to layout the inputs, outputs, outcomes and impact, but it also allows to establish ‘complex potential pathways and interactions between inputs and outputs. It helps to think about a policy as a set of multiple cause and effect pathways.

According to this approach, project designers must identify the logical ‘if-then-theory’ behind a policy intervention.The theory of change approach is intended to help project designers determine the scope of operational commitment, structure the operation, and communicate how the operation is (theoretically) expected to yield broader development impacts (and solve whatever problem the government is concerned about).

-Matt Andrews

Andrews further explains:

A planner implies that she knows (and there is agreement on this knowledge) what the end goals of the policy work are (and how to measure these and what current measures are), what outcomes and impacts will help to deliver these goals (and how to measure these and what current measures are), what inputs, activities and outputs will help to deliver these outcomes and impacts (and how to measure these and what current measures are), what the potential pathways and interactions between these inputs, activities, outputs and outcomes look like, who will be involved in every part of the work, where and when these parts of the work will occur, and—on top of it all—what assumptions underlie everything that is known, what risks are associated with those assumptions, and what pivots will be needed if risks transpire.

-Matt Andrews

While LFW and TOC are fine for planning and implementation purposes, the question is how should a policy maker gather information in the planning phase so that the policy that is intended to solve a problem, is effective. Does she/he know enough about the problem and prospective solutions?

To answer this question, Andrews has come up with a list of 25 questions that every policymaker should ask to gather as much information as possible during the planning phase. These questions are divided into 5 broad categories:

The purpose of the policy

People identified and engaged in the policy work

Are the solutions ‘clear and deliverable’?

Context of the policy

Processes that lead to effective implementation