Dispatch #57: From ‘Flailing State’ to ‘Dizzying State’?

In this dispatch we will revisit Pritchett's flailing state argument and will see whether in 2022, the head and the limbs of the Indian state are in co-ordination or not

In her 1994 essay titled ‘The Gentle Leviathan: Welfare and the Indian State’, political scientist Niraja Gopal Jayal argued that the Indian state is more of an interventionist state than a welfare one. According to Jayal India followed the state-driven capitalist path of development rather than the welfarist approach that the west adopted. In the 1960s, economist Gunnar Myrdal called India a ‘soft state’. A soft state has a weak law enforcement mechanism, low state capacity, and high levels of social indiscipline within the society. In their book, ‘In Pursuit of Lakshmi: The political economy of the Indian state’, the Rudolphs argued that India is more of a weak-strong state. There are dual forces that govern India, one is the centralized strong state that determines its centrist tendencies and the other is the weak state that has a complex relationship with the society. The weak state gives legitimacy to ‘highly mobilized fragmented forces that threaten governability, political stability, and national purpose’.

According to the Ruolphs, four factors led to the state weakness in India: deinstitutionalization of the Congress party; high levels of political mobilization; the antagonistic relationship between different castes and classes that often led to violence, and finally religious fundamentalism. To define the paradox of weak and strong Indian states, they have coined the terms such as ‘command polity model’ where the state is sovereign and authoritative, and ‘demand polity model’ where the citizens are sovereign and the state’s actions are restricted by societal norms.

In 2009, Lant Pritchett came up with his own provocative conceptualization of the Indian state. He called India a ‘flailing state’. He argued that:

India is today a flailing state---a nation-state in which the head, that is the elite institutions at the national (and in some states) level remain sound and functional but that this head is no longer reliably connected via nerves and sinews to its own limbs. In many parts of India in many sectors, the everyday actions of the field level agents of the state—policemen, engineers, teachers, health workers—are increasingly beyond the control of the administration at the national or state level.

-Lant Pritchett

Similarly, Devesh Kapur argued that the Indian state both fail and succeed at the same time because it is good at doing episodic activities (elections, Kumbh, and census) than performing quotidian activities (delivering public services).

Are these metaphors apt to define India, in 2022? Is the head (elite institutions) still strong while the limbs (frontline institutions) are struggling because of the unreliable connection via nerves and sinews, as Pritchett argued more than a decade ago?

Looks like the ‘flailing state’ has been turned upside down. In his latest essay for The Seminar titled ‘Has India’s flailing state been turned upside down?’, Milan Vaishnav has argued that in recent years while the elite institutions are facing severe crisis and there is a strong centralization of power by the executive, the frontline institutions, on the other hand, have done reasonably well to deliver private goods using public funds. Hence to use Pritchett’s 2009 metaphor, India in 2022 is a ‘dizzying state’ where the limbs are working fine but the head is in a disorienting state.

Vaishnav writes:

Recent evidence has neither affirmed nor negated Pritchett’s ‘flailing state’ construct; rather India may be experiencing the inversion of the concept. On the one hand, India’s elite institutions are suffering multiple crises of credibility. It is hard to think of one apex institution – from the Indian Administrative Service to the Election Commission of India (ECI) – that has seen its reputation improve since Pritchett published his essay more than a decade ago. On the other hand, India’s local development machinery is showing new signs of life. The welfare push of the Narendra Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government at the Centre, designed in Delhi but implemented by state and local authorities, has produced results that have pleasantly surprised even cynical observers. From toilets to gas connections, electricity hook-ups to bank accounts, the frontlines of the Indian state have managed to significantly expand the extent of India’s welfare net. In sum, it is an apt time to revisit Pritchett’s assessment, not only because India’s head has demonstrated new found weakness, but also because its limbs have shown surprising signs of effectiveness.

-Milan Vaishnav

Let’s take stock of both the ‘head’ and the ‘limbs’ of the Indian state.

In another article Vaishnav talks about the crisis faced by the ‘referee’ institutions of India such as the Supreme Court (SC), the Election Commission of India (ECI), and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

In 2018, the EC delayed in announcing the Gujarat state elections dates while declaring the same for others states having the same electoral calendars. The then Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) A.K. Joti said that the delay was due to the ongoing flood relief measures in the state. However, former CEC T.S Krishnamurthy disagreed with the CEC’s stand and said that the Model Code of Conduct can never come in the way of relief measures and the delay is just an ‘avoidable controversy’. In April 2019, just before the General Elections, a group of bureaucrats and diplomats wrote a letter to the President to share their concern on the ‘week knee conduct’ of the ECI after the Prime Minister’s announcement of India’s first anti-satellite (ASAT) test. The ECI’s silence on electoral bonds, frequent violation of the model code of conduct, and VVPAT issues have also questioned its credibility.

The SC’s crisis became evident in 2018 when 4 seniormost judges held a press conference to flag certain administrative issues in the working of the apex court. Justice Lokur said a few days ago that he was ‘terribly disappointed’ because the SC has not acted against the calls for genocide. Justice Lokur was so disappointed by the SC’s inability to hold the executive accountable while handling the migrant crisis during the first wave, that he said that the SC 'deserves an F grade for its handling of migrants.’

Even the quality of judgments has declined in recent years. According to this analysis, the number of citations from the judgments of the court has declined since 2014.

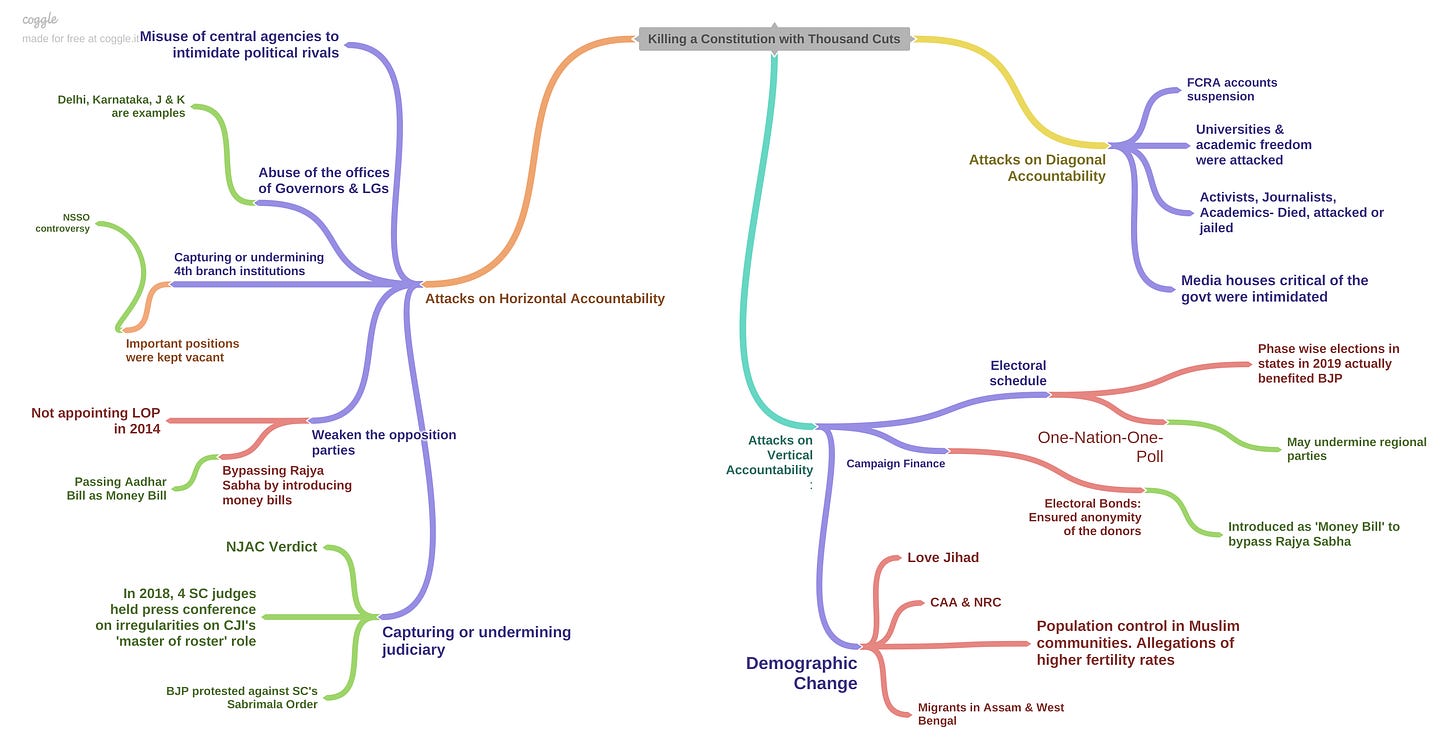

Other elite institutions like the RBI and the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) have also faced credibility issues in the past few years. In his brilliant essay, Tarunabh Khaitan elaborates on this phenomenon and calls it ‘killing a Constitution with thousand cuts’.

The limbs or the frontline institutions are instrumental in delivering the private goods using public funds and infrastructure such as toilets, bank accounts, houses, electricity, water, and even cash. Arvind Subramanian calls this the ‘New Welfarism’.

He explains:

The New Welfarism of the Narendra Modi government represents a very distinctive approach to redistribution and inclusion. It does not prioritise the supply of public goods such as basic health and primary education as governments have done around the world historically; it is also somewhat ambivalent about strengthening the safety net which past Indian governments have pursued with mixed success. Instead, it has entailed the subsidised public provision of essential goods and services, normally provided by the private sector, such as bank accounts, cooking gas, toilets, electricity, housing, and more recently water and also plain cash.

-Arvind Subramanian

Subramanian and others have found that the access to 4 essential services- cooking gas, electricity, toilet, and bank accounts have increased in the past 7 years.

The government’s single-minded focus on delivering these private goods can be assessed by reading the Economic Survey of India 2021 in which one full chapter was dedicated to the coverage of these goods. The survey calculated the Bare Necessities Index (BNI) by assessing the coverage of housing, water, sanitation, electricity, and clean cooking fuel. The survey claimed that between 2012 and 2018, the coverage of bare necessities has increased dramatically in India.

While the bare necessities goods might have a positive impact, the focus on other pressing or in fact ‘sticky’ issues has got diluted. Subramanian argues that during the same time period in which the coverage of basic necessities has improved significantly, child malnutrition in India has also increased. For him, this is a story of retrogression and not of progress. The ‘New Welfarism’, as he calls it, means using public funds to provide private goods to the citizens as basic needs, while withdrawing focus on distributing public goods widely. The New Welfarism approach not only consists of conviction but also of calculation. Conviction of providing goods and services in order to improve the living conditions of the recipients; calculation of providing tangible private goods that can be measured and can later be benefited for electoral purposes.

The government will continue to pursue the New Welfarism at the cost of investing in the higher institutions since that strategy is giving them good electoral returns.

While the elite federal institutions have faltered the political centralization has increased. This centralization has made sure that the credit for the success of the schemes to distribute essential services goes to the government and the PM. There’s growing evidence that the centralization of political power, stymying of higher institutions, and ensuring that the bureaucracy delivers the private goods and services have resulted in positive electoral outcomes for the BJP. The frontline bureaucracy is complemented with a whole host of non-government entities and players to make sure that the goods and services reach out to the beneficiaries and there is a positive feedback loop that gives credit to the government.

These schemes gained wide recognition among voters. Analysis of the postelection 2019 National Election Survey highlights that a larger share of voters identified themselves as beneficiaries of the BJP governing coalition’s signature programs than had ever done so with regard to the programs of the Congress-led coalition (known for its expansive welfarism) that governed between 2004 and 2014.

-Yamini Aiyar

Technology played a vital role in helping the government to deliver essential services to the voters.

Tillin, Deshpande, and Kailash write:

It has gone to great lengths to underline the point that the use of technology and direct benefit transfers has helped weed out fake beneficiaries who were receiving various subsidies. This line is very similar to the European right, who too aim to ‘reclaim’ those services from the ‘bureaucrats’ and ‘welfare scroungers’ that ‘abuse them’ at the cost of their ‘rightful owners’: the common man who is falling on hard times. The government claimed that when non-existent beneficiaries were removed, public money was being saved and it also showed the corruption free nature of this government.

-Tillin and others

Towards the end of his essay, Vaishnav cautions the readers that the ‘dizzying state’ can have a very different effect on Indian democracy, politics, and public service delivery.

He says:

The narratives built around the rehabilitation of India’s lower level ‘limbs’ should not overstate the case. There is good reason to interpret recent gains with caution.

First, the thrust of the new welfare push has not been based on improving the quality of public goods, but instead on ramping up the public distribution of private goods. Second, the prioritization of visible goods that can be provided in a short time horizon over less visible goods requiring long term, structural reforms. Building a toilet for an underprivileged household that lacks proper sanitation represents a concrete benefit with a clear pay-off in a limited time horizon. The tangible nature of the good also increases voters’ recall value at the time of elections. Fixing the public education system, on the other hand, is far more complex. Concrete gains are unlikely within a single, five-year term. Changes to the ‘software’ of policy – the stuff of curricula, teacher training, and pedagogy – as opposed to the ‘hardware’ (school infrastructure) are not easily observable to ordinary citizens.

-Vaishnav