Dispatch #60: Different shades of ‘policy implementation success’

In this dispatch we look into different dimensions of policy implementation success and complex system nature of public policies

How do we define a policy implementation success? When do we say that a public policy was a success- when it is effective or when it is efficient? Even if we broadly define policy success, how do we measure it? Are the current tools that the global policy community enough to measure policy outcomes? And more importantly what are policy failures? Do we know enough about them? These are the questions that I have grappled with in my older dispatches here and here.

My ever-growing interest in identifying frameworks for public policy implementation success led me to discover Allan McConnell's paper and Matt Andrews’s latest working paper on the subject.

Before we delve deeper into policy success, first let’s define public policy. Matt Andrews defines public policy as ‘the work government does through public policy officials to solve society’s problems and address its future needs.’ What happens when the policy fails? Andrews answers by adding that ‘the current problems will go unsolved, further needs will be unmet, society’s resources will be wasted and government may lose trust and legitimacy’.

Now let’s look at policy failure. According to Bernardo Mueller, a public policy fails because it operates within ever-evolving and ever-changing complex systems. A complex system is ‘one in which diverse agents linked in networks interact selectively following simple rules without centralised control, and from which emerges (often unpredictable) patterns, structures, uses and functionalities, never settling on definitive equilibria, but always learning, adapting and evolving.’ Public policies are embedded withing such complex systems and therefore it’s often hard to control and predict the outcomes. Mueller has identified five pathologies that can help us in understanding the complex system nature of public policies:

Public policies are non-linear and emergent: The final effect of a public policy is never the sum of effect of its various parts and the results can’t be predicted by looking at individual parts.

Public policies do not settle in equilibria and are hard to predict: Because policies are non-linear, emergent and arise from iterative interactions of several agents, it is hard to predict the outcomes.

Public policies evolve and co-evolve: Public polices are impacted by culture, beliefs, institutions, norms and technology. These things change and evolve over time, thus impacting public policies.

Public policies are subject to cognitive biases: The rational choice theory according to which agents have a fixed set of preferences that guide their choices, does not apply in case of public policies.

Public policies suffer from reactivity: The winners or the losers of any public policy strategically change their behaviour in reaction to the knowledge that a new policy in being implemented.

Coming back to public policy success.

There are several ways to look at policy implementation success. University of Sydney’s Allan McConnell relates policy success with goal attainment. For him, a policy is successful ‘if it achieves the goals that proponents set out to achieve and attracts no criticism of any significance and/or support is virtually universal.’ McConnell identifies three dimensions of policy success:

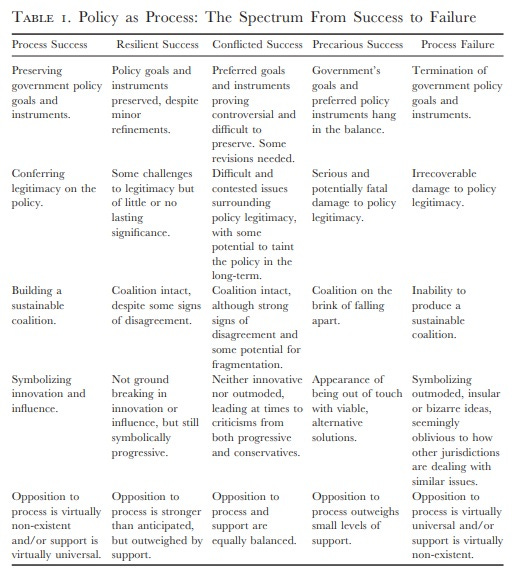

Process: How governments identify problems, find out alternatives to solve the problems, do consultations and take decisions. All these activities involve weighing the pros and cons of different choices such as ‘who, when and how to consult’. The activities also include weighing the opportunities and risks of different policy alternatives. Governments ‘do process and they may succeed and/or fail in this realm.’

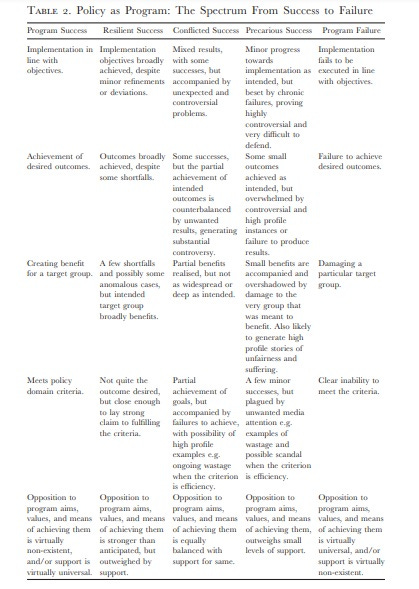

Programs: This is what governments do. They convert the generalised intentions of statements into concrete actions using resources and tools such as laws, tax, manpower, expertise and incentives.

Politics: This is related to the policy’s political repercussions that will impact the reputation and the electoral prospects of the political class.

The biggest contribution of McConnell’s paper is that by using these three dimensions, he has mapped policy success and failure. So for example a policy is successful if there is the least resistance to the government in implementation and there is wide-ranging support. On the other hand, a policy fails when it loses legitimacy and the opposition is universal. Process success happens when the government’s policy goals and instruments are preserved, the policy gains legitimacy, it helps in building a sustainable coalition and promotes innovation.

Similarly, the program success happens when the implementation is in line with the objectives, the policy has achieved desired outcomes while creating benefits for a target group.

Likewise, political success happens when a policy succeeds in enhancing electoral prospects or the reputation of political actors.

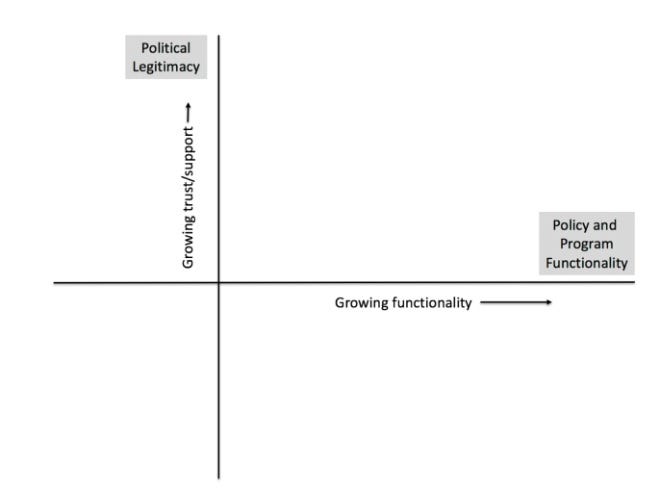

Matt Andrews uses another framework to define policy implementation success. He considers two dimensions of success:

Functionality: Focuses on what is done in a policy and why is it done. Essentially, a policy is considered a success if it solves the problem it is created to solve. It covers McConnell’s ‘program’ dimension.

Legitimacy: Focuses on how a policy is done and whether it attracts the confidence and support of the people. It covers McConnell’s ‘process’ and ‘political’ dimensions.

If we plot functionality (program success) and legitimacy (process and political processes) on a chart, then we can easily conclude that policy success happens with increased levels of functionality and legitimacy.

Watch this wonderful short lecture by Matt Andrews on how policy analysts can use an iterative process to gain both functionality and legitimacy.

Sir, this is excellent! Thank you so much