Dispatch #61: Indian status syndrome

In this dispatch we will look at the recent studies that highlight disparities in life expectancy among different social groups in India. Additional sections on research and book recommendations.

In 1967 a study was conducted among male British civil servants who were in the age group of 20-64 years. The study investigated the correlation between the ranks or social status of the civil servants and the prevalence of cardiovascular disease and mortality. It examined nearly 17,000 civil servants for a period of ten years. Since the study was conducted in the Whitehall area of London, it was named the Whitehall Study and was led by Michael Marmot. The study found that the mortality rates were higher among the low-rank civil servants in contrast with the mortality rates of high-rank civil servants. Marmot highlighted the association between the stratification of British society and health, in the Whitehall study. He coined the term ‘status syndrome’ to describe the association between a person’s social status and health outcomes.

In his 2004 book, Status Syndrome, Marmot claims that ‘where you stand in the social hierarchy is intimately related to your chances of getting ill and life expectancy’. In the past several decades the world has become healthier and wealthier. The life expectancy has increased, diseases have been eradicated by human ingenuity and science and research, lesser number of children are dying before their fifth birthdays, yet all these outcomes are better for some than others. Marmot explains this in simple terms by saying, ‘wherever we are in the hierarchy, our health is likely to be better than those below us and worse than those above us’.

Marmot explains:

The higher the status in the pecking order the healthier they are likely to be. In other words, health follows a social gradient. I call this the Status Syndrome.

But, how does an individual’s economic status or material well-being impact health outcomes?

They certainly do but in a limited sense. So in terms of access to healthcare services and health behaviour, the economic status is detrimental. But Marmot argues that beyond material well-being, it’s autonomy or an individual’s degree of controlling one’s life that becomes central to health outcomes. Later in this article, we will look at the evidence from India that point us to the fact that even at higher levels of wealth, the difference in life expectancy between marginalised and dominant social groups persists.

Marmot further adds:

For people above a threshold of material well-being, another kind of well-being is central. Autonomy-how much control you have over your life- and the opportunities you have for social engagement and participation are crucial for health, well-being and longevity. It is inequality in these that plays a big part in producing the social gradient in health. Degrees of control and participation underlie the status syndrome.

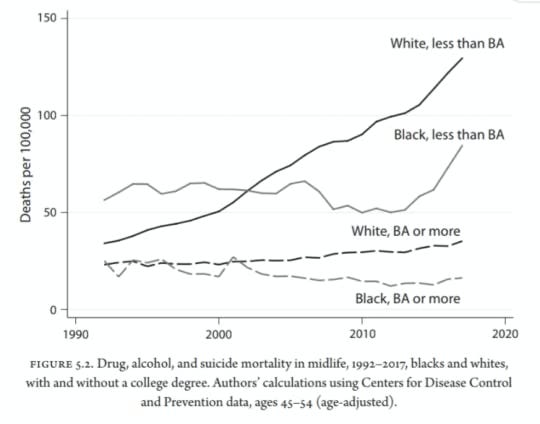

In their extremely well-researched book ‘Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism’, Anne Case and Angus Deaton have highlighted the three ‘deaths of despair- deaths from a drug overdose, suicide and alcoholic liver disease- that have killed nearly 158,000 Americans since the 1990s. Case and Deaton claim that the deaths of despair pose a great risk to less-educated white Americans. One cannot pinpoint a date or a year when these deaths started mounting up in the US but the authors say that ‘deaths of despair were rising before the recession, they rose during the recession and they rose after the recession; there is no sign of recession in the mortality numbers”. These deaths specifically target white middle-aged Americans without a four-year college degree. The authors, through their research, have established that the lack of a graduate degree and the transition in the economy, technology and hence the job market, have rendered most Americans redundant. As a result, the decline in wages and social status acts as a preeminent trigger of the deaths of despair

.One can see a very similar pattern in the case of suicide data in India. Nearly 87% of suicide victims in 2020 were those who did not do any diploma, graduation or professional degree according to the NCRB data.

Recent studies by Indian researchers have shown a similar social gradient in health. It should not come as a surprise that in a highly stratified society like India, social groups will have disparities in mortality rates and other health indicators.

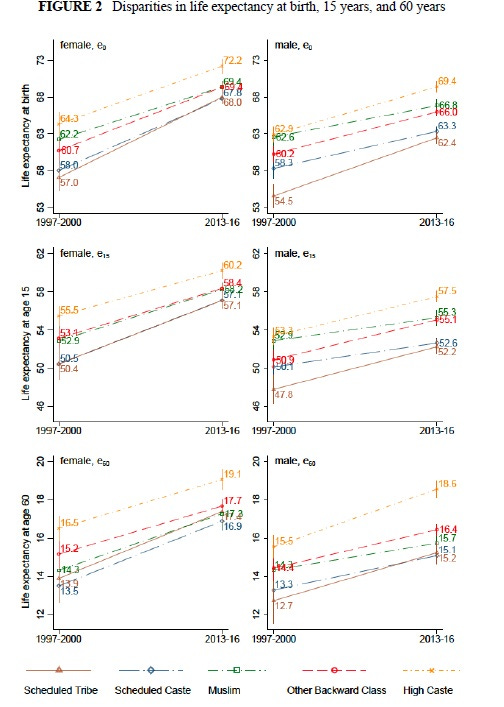

In the paper titled ‘Large and persistent life expectancy disparities between India’s social groups, scholars Aashish Gupta and Nikkil Sudharsanan, find out ‘how large are social group differences in life expectancy in India and how have they changed in 20 years’. Using the NFHS data, they found that there are wide disparities in life expectancy of individuals from weaker social groups (SC and ST) as compared to high caste. These disparities can be seen at birth, 15 years and 60 years.

While the overall life expectancy levels of all social groups increased over decades, the gaps between other social groups still remain. For example, the difference in life expectancy at birth of women from high caste and from a scheduled tribe has decreased from approximately 7 years to 4 years from 1997-2000 to 2013-16. The expectancy increased but the gap persists.

The authors have further investigated regional differences in life expectancies at birth in 2013-16. To do this they divided India into 6 regions: North India, the Hindi belt, West, South, East and North East. In the chart below, darker shades denote a larger difference in disparities.

The disparities between life expectancies of SC and high caste are high in the Hindi belt, both for men and women. Interestingly, the difference between life expectancies at birth between SC and high caste is highest in South India. Even with their superior health infrastructure and health care delivery services, southern states have not been able to bridge the life expectancy gaps between the SC and upper caste. Similarly, the disparities between ST and high caste are high, both in men and women, in the Central Indian states where the ST population is dominant.

The authors conclude that:

Social differences in longevity in India are exceptionally large in the context of global health disparities. In comparison to race in the United States, we find that castedifferences in life expectancy in India are larger in an absolute sense and even more pronounced when considered as a percent difference, since the overall levels of life expectancy in India are lower. Mortality disparities in India are comparable to disparities in other severely stratified contexts, such as between Arabs and Jews in Israel; between indigenous and white residents in New Zealand, Australia, or Canada; and by race in Brazil. The salience of the mortality disparities we document is heightened when considering that the combined population size of any two of these three marginalized social groups is as large as the population of the United States.

In another study titled ‘Social disadvantage, economic inequality, and life expectancy in nine Indian states’, Sangita Vyas and others investigated ‘life expectancy differentials along lines of caste, religion, and indigenous identity in India’. These nine states are- Assam, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, and Uttarakhand. They represent nearly 48% of India’s population.

The study finds that:

Compared to high-caste Hindus/OBCs, we observe lower life expectancies at birth among marginalized social groups. Adivasis have the lowest life expectancy among the four groups. Differentials between Adivasis and higher-caste Hindus are 3.7 years for women and almost five years for men. The gap between Dalits and higher-caste Hindus is of similar magnitude: more than 3 years for both women and men. Muslim life expectancy is about one year less than that of higher-caste Hindus. Both overall levels of mortality among marginalized social groups and the absolute differentials between groups are comparatively large. Life expectancy for Dalits and Adivasis is similar to those of the poorest countries in the world.

Individuals from marginalized groups are also poorer. So, are these disparities in life expectancies among the groups driven by levels of wealth only? Or these disparities are also seen at higher wealth levels?

According to Vyas and her co-authors, the difference in life expectancy is present at higher levels of wealth among Dalits and tribals.

The authors conclude by arguing:

From a policy perspective, these findings suggest that population health interventions that explicitly challenge social disadvantage are essential because addressing economic inequality may not be sufficient. Unfortunately, health policy in India and globally largely ignores caste, religion, exploitation, and discrimination. This study justifies further action on social disparities in health within India, and advances the global conversation addressing inequalities based on race, ethnicity, indigenous identity, caste, and religion.

Research recommendation

Estimates and correlates of district-level of maternal mortality ratio in India: Using the Health Management Information System (HMIS) data, for the first time this study estimates the Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) for all 640 districts from 29 states and 7 Union Territories.

Main findings:

Considerable geographical heterogeneity in MMR across Indian states.

While southern states have overall low MMR, within-states variations also exist. For example ‘some districts in Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, and Telangana also have MMR above 140, despite all four states falling in the category of MMR below 70 at the state level’.

Book recommendation