Dispatch #63: Revisiting 'The Idea of India'

As Sunil Khilnani's 1997 book completes 25 years, in this dispatch we revisit critical passages from the book on Indian democracy, history, society and everything else that encompasses ‘the idea’

“When I wrote The Idea of India in 1997, I wanted to show that the founding idea of India is anchored as much in resisting certain powerful seductions- the temptations of a clear, singular definition of nationhood, of the apparent neatness of authoritarian politics, of the clarities of a statist or pure market economy, of unambiguous alliances with other states-as it was in realizing declaratory visions”.

That was Sunil Khilnani (SK), in the introduction of the 2012 edition of his book. The book is about India’s public life after independence and focuses on the ‘turbulent, intricate and decisive passage of history’ since its independence in 1947. Written in 1997, it takes stock of the 50-year-old republic and evaluates whether we have been able to ‘redeem our pledge’, half a century after we ‘made a tryst with destiny’.

While he exuded a lot of hope in the introductory chapter by pointing out the rapid changes India was witnessing a decade ago, he was also cautious about the challenges that lay ahead. His concerns seemed to be prophetic after 25 years.

I was motivated, back then, by a different kind of concern about India’s democracy: a certain kind of majoritarianism, it seemed, might threaten our foundational commitment to diversity and pluralism.

In the mid-1990s, India had emerged from a deep economic crisis, only to ensnare itself in battles over identity. What sort of a nation were we? Which groups or cultures had the right to claim special privileges? Religion, caste, region: all were vigorously advanced as answers.

The book has four chapters, namely- Democracy, Temples of the Future, Cities and Who is an Indian, an introduction and an epilogue titled, The Garb of Modernity. In this dispatch, we will revisit some of the critical passages of the book that have stood the test of time and are still relevant today.

Introduction

Three purposes the book would serve if it manages the readers to rethink the Indian story

In the first instance, the history of independent India can be seen, most narrowly but also most sharply, as the history of a state: one of the first, largest and poorest of the many created by the ebb of the European empire after the end of the Second World War. The arrival of the modern state on the Indian landscape over the past century and a half, and its growth and consolidation as a stable entity after 1947, are decisive historical facts. They mark a shift from a society where authority was secured by diverse local methods to one where it is located in a single, sovereign agency. Seen in this perspective, the performance of the Indian state invites evaluation by external and comparative standards: for example, its ability to maintain the territorial boundaries it inherited from the British Raj, to preserve its domestic authority and the physical security of its citizens, to act as an agent of economic development, and to provide its citizens with social opportunities. Unlike the states of modern Europe, which acquired these responsibilities in gradual sequence, new states like India have had to adopt them and be seen to pursue them, rapidly and simultaneously. The ability of a modern state to meet these heavily instrumental criteria is undoubtedly crucial to the life chances of its citizens. But these responsibilities have raised expectations often very distant from the state’s practical capacities.

The period of Indian history since 1947 might be seen as the adventure of a political idea: democracy. From this perspective, the history of independent India appears as the third moment in the great democratic experiment launched at the end of the eighteenth century by the American and French revolutions. Each is a historic instance of the project to resuscitate and embody the ancient ideal of democracy under vastly different conditions, where the community is no longer held together by a moral ideal or conception of virtue but must rely on more fitful, volatile solidarities and divisions including those produced by the exigencies of industrial production and commercial exchange. Each of these experiments released immense energies; each raised towering expectations; and each has suffered tragic disappointments. The Indian experiment is still in its early stages, and its outcome may well turn out to be the most significant of them all, partly because of its sheer human scale, and partly because of its location, a substantial bridgehead of effervescent liberty on the Asian continent.

The most imaginatively ambitious if also an analytically elusive perspective on India since 1947 shows a rapid acceleration and intensification in the long-running encounter between a civilization intricately designed with the specific purpose of perpetuating itself as a society, a community with a shared moral order, one of the world’s most sophisticated assemblages of ‘great’ and ‘little’ traditions, and, set against it, the imperatives of modern commercial society. This is presumed somehow to link a political order that enshrines individual rights and representation to an economic system of private property rights and market exchange – but it stands under permanent threat of being unable to reproduce itself, and is fundamentally unstable. Seen from this angle, the many civilizational strands on the Indian subcontinent have uncomfortably but inescapably been confronting modernity: a seductively wrapped and internally inconsistent mixture of instrumental rationality, utilitarianism, and respect for individual autonomy and choice. From this perspective, one can focus on the question of whether culture and its members can sustain their distinctive character once they entrust their destiny (as they must) to a modern state.

Democracy

India as democracy remains a defiant anomaly

Few states created after the end of the European empire have been able to maintain democratic routines; and India’s own past, as well as the contingencies of its unity, prepared it very poorly for democracy. Huge, impoverished, crowded with cultural and religious distinctions, with a hierarchical social order almost deliberately designed to resist the idea of political equality, India had little prospective reason to expect it could operate as a democracy. Yet fifty years later India continues to have parliaments and courts of law, political parties and a free press, and elections for which hundreds of millions of voters turn out, as a result of which governments fall and are formed. Democracy is a type of government, a political regime of laws and institutions. But its imaginative potency rests in its promise to bring alien and powerful machines like the state under the control of the human will, to enable a community of political equals before the constitutional law to make their own history. Like those other great democratic experiments inaugurated in eighteenth-century America and France, India became a democracy without really knowing how, why, or what it meant to be one. Yet the democratic idea has penetrated the Indian political imagination and has begun to corrode the authority of the social order and of a paternalist state. Democracy as a manner of seeing and acting upon the world is changing the relation of Indians to themselves.

Brahminic order in pre-colonial India and the absence of state & politics

The Brahminic order in India was certainly an oppressive system of economic production, and it enforced degrading rules about purity and pollution. But its capacity to endure and retain its grip over a wide geographical area flowed from its severely selective distribution of literacy. The Brahminic pattern survived not through allying with temporary bearers of political power, nor by imposing a single belief system on the society. Rather, it cultivated a high tolerance for diverse beliefs and religious observances, withdrew from political power – the realm of Artha, or mere worldly interest – and directed its energies towards the regulation of social relationships; it made itself indispensable to the conduct of essential rituals, and it provided law for every aspect of social life. Its interpretative powers were recognized as the ultimate sanction and authority for caste rules. By renouncing political power, the Brahminic order created a self-coercing, self-disciplining society founded on a vision of moral order. This society was easy to rule but difficult to change: a new ruler had merely to capture the symbolic seat of power and go on ruling as those before him had done. India could be defeated easily, but the society itself remained unconquered and unchanged.

Politics was thus consigned to the realm of spectacle and ceremony. No concept of a state, an impersonal public authority with a continuous identity, emerged: kings represented only themselves, never enduring states. It was this arrangement of power that explains the most peculiar characteristic of India’s pre-colonial history: the perpetual instability of political rule, the constant rise and fall of dynasties and empires, combined with the society’s unusual fixity and cultural consistency. Its identity lay not in transient political authority but in the social order. The ambitions of political rulers could therefore never become absolute, as they readily became in Europe: the rulers could not transform or mobilize society for particular ends. The state as a sovereign agency with powers to change society, to alter its economic relations, to control its beliefs or rewrite its laws, did not exist. The political authority that the many territorial kingdoms of the Indian subcontinent possessed was more a matter of paramountcy than sovereignty: kingship was exercised through overlapping circuits of rights and obligations that linked together diverse local societies but also sheltered them from the intrusions of any one ruler. Rulers restricted themselves to extracting wealth in the form of rent; they had no means to rearrange the property order or effect large shifts in the balance of wealth from one group to another, and thus secure permanent allies.

Unlike the history of Europe, that of pre-colonial India shows no upward curve in the responsibilities and capacities of the state. The very externality of politics, its distance from what was taken to be the moral core of the society, was the key to the society’s stability.

The interaction between the state, British laws and Indian society amidst paternalistic utilitarianism

After the mid-nineteenth century, resolutely this-worldly political doctrines of utilitarianism dominated, but by the time their remedies began to surface in the ordinances of British administrators in Calcutta and Bombay, their original radical impulse had wilted into what has been called ‘Government House utilitarianism’, a decisively authoritarian and paternalist vehicle for the ideas of intellectual bullies like James Fitzjames Stephen. The corrective accent inspired zealous administrators to enlarge the field of Raj’s activities: it began to pry into Indians’ social customs and habits, legislated the abolition of sati (an interference in social customs by the political authority without historical precedent in India) and established the principle – if a rather deformed conduct – of representative politics.

Group rights versus individual rights

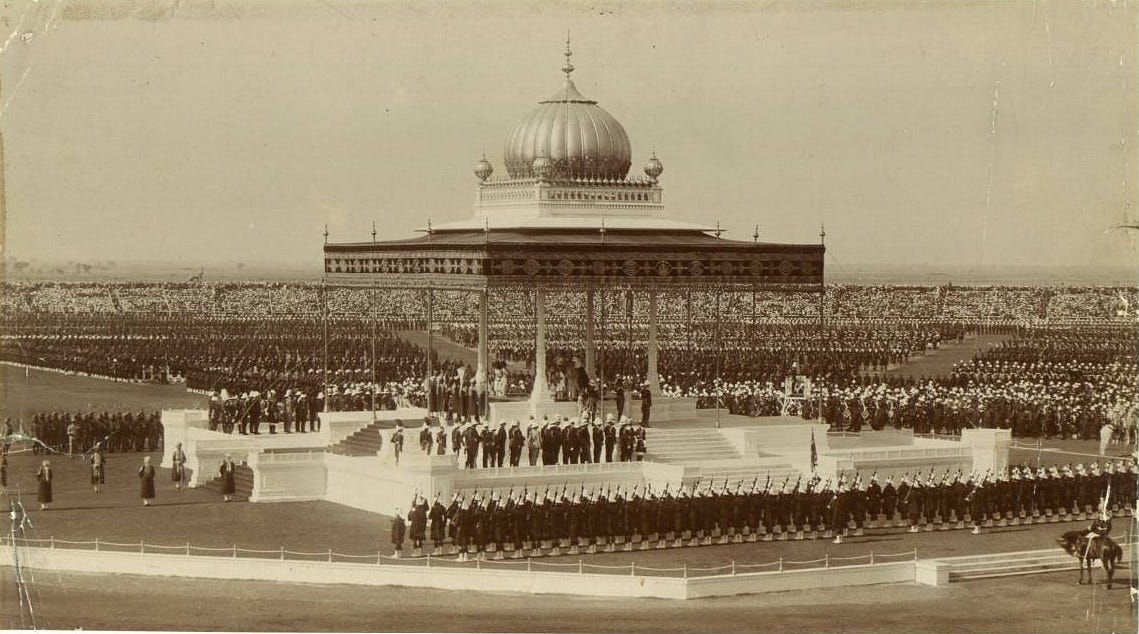

The language of representative politics entered India through a utilitarian filter, at a time when British liberalism was at its most rampantly collectivist and paternalist. The possible forms of liberalism in India were still further reduced. The idea of natural rights, essential to modern liberalism, was only faintly articulated and failed to find a niche in nationalist thought. The interests of Indians, the British had decided, could not be individual. It followed that when elections to provincial legislatures were first introduced – as a result of constitutional reforms devised in 1909 by the Secretary for India, John Morley, and the Viceroy, Lord Minto – the units of representation were not defined (as they were in Britain) as territorial constituencies containing individuals with rights and changeable interests. The legislatures of British India’s administrative provinces, arbitrarily demarcated territories, represented societies of communities, not individuals. The extent of that representation did widen over time, being increased by the 1919 Montagu-Chelmsford reforms which granted to Indians for the first time the principle of responsible government, and most of all by the Government of India Act of 1935, which established the Raj as a federal structure and brought more Indians into its administration; but even then, less than one-third of Raj’s subjects had the vote (the subjects of princely India – a quarter of the subcontinent’s population – remained altogether excluded).

Indian liberalism, stamped by utilitarianism

Liberty was understood not as an individual right but as a nation’s collective right to self-determination. It is hardly surprising that the individualist accent was muted: Indian society did have a place for the individual, but in the form of the renouncer, a category relegated to the margins of the society. Individuality as a way of social being was a precarious undertaking. All this left Indian liberalism crippled from its origins: stamped by utilitarianism, and squeezed into a culture that had little room for the individual.

India’s founding moment and the role of Nehru

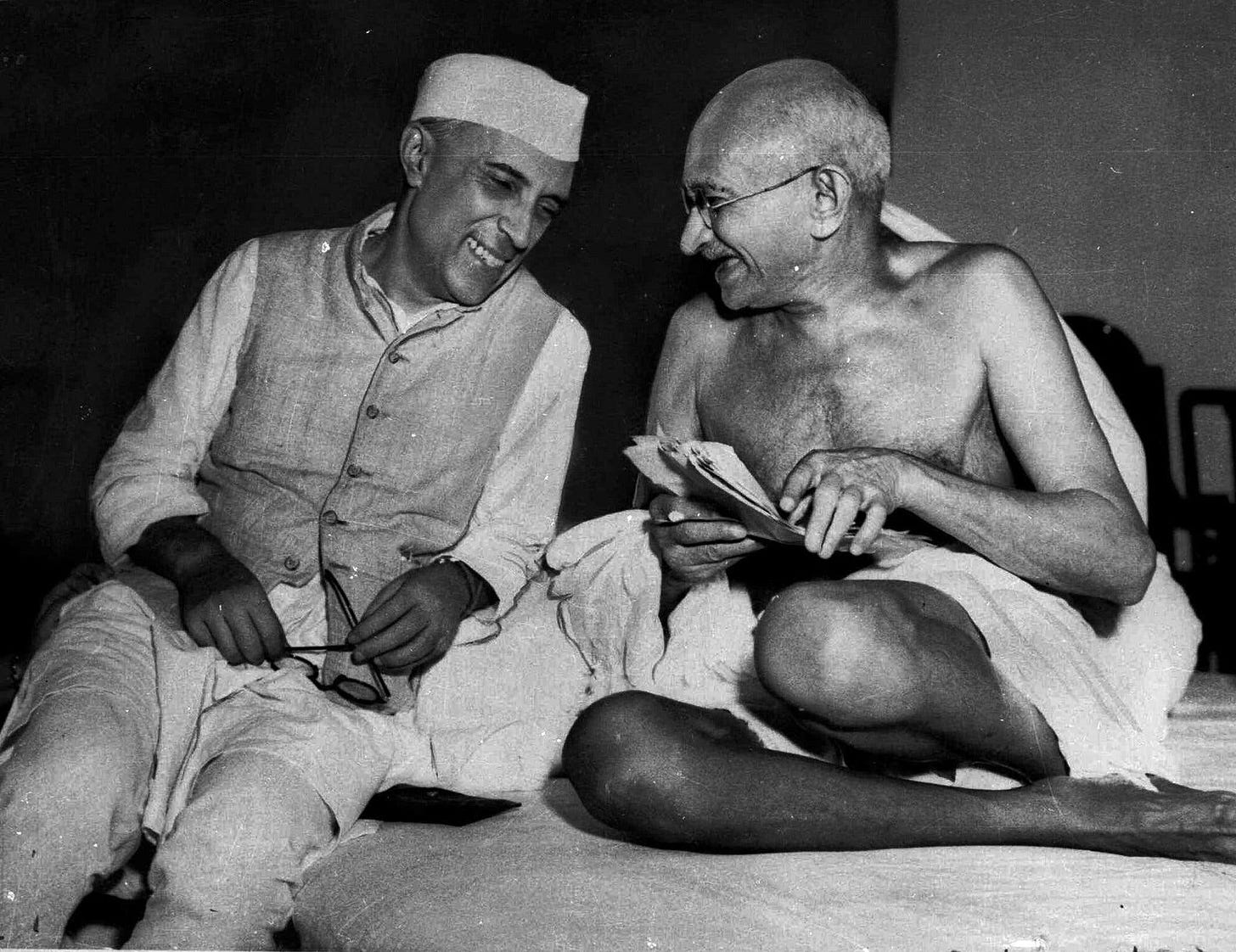

When Congress inherited the undamaged coercive and bureaucratic powers of the British Raj in India, and the major part of its territory, the circumstances were ones of uncertainty and crisis. The nationalist élite in command of the state had to act in a society alive with aspirations, divided between differing conceptions of who the nation was and what the state should do. Congress was in dispute with itself: Partition had emboldened its Hindu voices, meanwhile those on the socialist Left had exited, and Gandhi in characteristically gnomic fashion called for Congress’s dissolution now that the appointed day had come and gone. It was far from inevitable that the Indian state would emerge from this flux as a parliamentary democracy based on universal suffrage, without religious affiliation and committed to social reform. Strong pressures were weighing the other way: towards a more traditionalist kind of state, tied to religion and defending the existing order.

The contingencies that put Nehru in control of his party and then over the state of independent India in August 1947 were decisive. But his was always a tenuous dominance, and throughout his career as prime minister Nehru was an isolated figure, having to act against the inclinations of both his party and the state bureaucracy. In the history of the Indian state, this inaugural span, from 1947 until Nehru’s death in 1964, is of unsurpassed importance, during which the state stabilized, became a developmental agency that aspired to penetrate all areas of the society’s life, and showed that it could be subject to democratic procedures. But the settled coherence of the Nehru era is in fact a retrospective mirage. He did have intellectual principles and a philosophy of history, both of which shaped his actions, and there were certainly others who shared his views, but he had no clear doctrinal plan of action, nor was there anything like a consensus, within either his party or the society at large, to impart cohesion. Nehru’s view of historical possibility was determined by his understanding of the West’s historical trajectory, in which he saw universal significance. He was convinced that to maintain their newly won independence, Indians would have to entrust their future to a national state, whose central responsibility would be to direct economic development; but it also had to build a constitutional, non-religious regime, extend social opportunities, and maintain sovereignty in the international arena. This expansive and imprecise vision became tangible after 1947. Nehru’s argument was not ideological or theoretical: it emerged through constant practical adjustments in the face of political contingencies.

Constitutional Democracy: India’s giant leap of faith

Constitutional democracy based on universal suffrage did not emerge from popular pressures for it within Indian society, it was not wrested by the people from the state; it was given to them by the political choice of an intellectual élite. The Constituent Assembly was a remarkably unrepresentative body: around 300 men (more were added after the princely states entered the Union), elected on the restricted franchise of the provincial legislatures, and overwhelmingly dominated by the upper-caste and Brahminic élites within Congress. There was no organized representation of India’s Muslims, no presence of Hindu communal groups (although Congress itself harboured many Hindu conservatives) and, after 1948, no socialist voice. To Gandhi, for instance, it was quite clearly not a sovereign body. Within the Assembly itself, the drafting of the Constitution rested in the hands of only about two dozen lawyers.

Most people in India had no idea of what exactly they had been given. Like the British empire it supplanted, India’s constitutional democracy was established in a fit of absentmindedness. It was neither unintended nor lacking in deliberation. But it was unwitting in the sense that the élite who introduced it was itself surprisingly insouciant about the potential implications of its actions. The ample volumes of the Constituent Assembly debates contain superbly turned pieces of forensic reasoning, speeches about the relationship between the executive and the judiciary and about the optimum length of a presidential term. Yet they carry little trace of the classic fears that haunted both advocates and critics of democracy in nineteenth-century Europe: what would happen if the vote was given to the poor, the uneducated, the dispossessed? B. R. Ambedkar, the formidable leader of India’s ‘untouchables’ – upon whom the caste system branded its most brutal stigmata of oppression – put the point searingly in a majestic closing discourse to the Assembly debates:

On the 26th of January 1950, we are going to enter a life of contradictions. In politics we will have equality and in social and economic life we will have inequality. In politics we will be recognizing the principle of one man one vote and one vote one value. In our social and economic life, we shall, by reason of our social and economic structure, continue to deny the principle of one man one value. How long shall we continue to live this life of contradictions? How long shall we continue to deny equality in our social and economic life? If we continue to deny it for long, we do so only by putting our political democracy in peril.

This fundamental contradiction, along with others, was inscribed in India’s interminably long Constitution. The Constitution did not express the opinions or preferences of Indians, nor did it confine itself to a bare statement of procedural rules. It was a baroque legal promissory note, its almost 400 articles embodying what initially looked like a derisorily ambitious political design. Yet, despite some serious mishandling, it has had a commanding influence over India’s subsequent history, representing an ideal of legality and procedural conduct – albeit regularly ignored with sublime talent by Indians at all levels – that has loomed in public life as a permanently embarrassing monument. The Supreme Court, its defender and interpreter, became a central institution of the nation’s public life, resorted to by rich and poor, literate and illiterate.

Establishing the state and democratic institutions

The true historical success of Nehru’s rule lay not in a dissemination of democratic idealism but in its establishment of the state at the core of India’s society. The state was enlarged, its ambitions inflated, and it was transformed from a distant, alien object into one that aspired to infiltrate the everyday lives of Indians, proclaiming itself responsible for everything they could desire: jobs, ration cards, educational places, security, cultural recognition. The state thus etched itself into the imagination of Indians in a way that no previous political agency had ever done. This was the enduring legacy of the Nehru period. Democratic habits rapidly became hollow routines, and a bare decade after his death in 1964, his daughter had initiated the country into a very different politics. Perhaps it is unreasonable to have expected this brief and overactive period in Indian history to have installed invulnerable institutional structures. At the time, Nehru’s achievement looked more solid than it was, a trick of his own formidable intellectual capacity to give shape to his projects, to tell persuasive stories about the significance of his actions. There was undoubtedly an element of selfpersuasion to this: clear, for instance, in his resolution to treat the leaders of the tiny non-Congress parties in parliament as if they were genuine opposition leaders, in order to instil the habits of parliamentary democracy in India. The Nehru period made plain the centrality of leadership in the Indian state.

The unique electoral democracy of India

The unstoppable rise of popular engagement in electoral politics, the fact that in a national study conducted in 1996 more than 70 per cent of the electorate rejected the suggestion that India would be better governed without political parties and elections, attests to the authority of the democratic idea. Yet the meaning of democracy has been menacingly narrowed to signify only elections.

But more generally, other democratic procedures have weakened with neglect. In any modern democracy elections are part of a larger set of rules and practices designed to authorize the state, but in India they are carrying the entire burden of society’s aspirations to control its opportunities. As the sole bridge between state and society, they have come metonymically to stand for democracy itself; their very simplicity, their conversion since the 1970s into referenda where voters were offered simple choices, have made them universally comprehensible. This expansion of elections to fill the entire space of democratic politics has altered how political parties now muster support. The most recent period of India’s democracy has shown a tenacity of community identities, in the form of caste and religion, as groups struggle to construct majorities that can rule at the Centre. But the fact that such identities were less significant for four decades after independence, and then surged into national politics, only shows how much they are creations of modern politics, not residues of the past.

Temples of the future

Economic dilemma of the independent India

At the root of the conflict was Gandhi’s sweeping dismissal of industrial modernity. To Visvesvarayya’s technocratic battle-cry ‘Industrialize – or Perish!’ Gandhi replied, ‘Industrialize – and Perish!’ The trivial seductions of commercial and industrial society, with its glittering baubles and trinkets, were exactly what had first enslaved Indians to the British. The purpose of winning swaraj, self-rule, Gandhi daily insisted, was to emancipate Indians from the compulsion to imitate the imprisoning, destructive and iniquitous forms of industrial modernity dumbly cherished in the West. The solution to India’s poverty was not a matter of state policy, tractable in terms of Western economics; indeed, ‘imitation of English economics’ would spell India’s ruin.

As independence approached, the contradictions between these different visions sharpened. The nationalist élite addressed itself through a flurry of ‘plans’. But the manifestos of the intelligentsia and the industrialists were at some remove from the kind of party that Congress had by now become. By the late 1930s, it depended more than ever on the powerful in the countryside, who were uninterested in industrialization or in the redistribution of wealth and power. The entry of Congress into the provincial electoral politics of the Raj would henceforth practically constrain the imaginative visions of the progressive intellectuals. It bound the party to alliances and commitments that came to dominate India’s politics until at least the 1960s. To win, Congress had to carry the support of the upper-caste rural land-lords and richer farmers; and after 1947 it continued to rely on them to deliver the votes of those lower in the social order. And to keep the support of the rural rich, Congress had in practice to soften its redistributive intentions and agree to leave decisions about the rural property order in the hands of the men who dominated it. This mixed identity of Congress, joining the high-status urban élite to the wealth of the countryside, made it an unbeatable political machine.

The basic dilemma of independent India’s pursuit of economic development was presaged here: in a country where the great weight of numbers, and considerable wealth, lay in the countryside, there were relatively few pressures to industrialize, still less to redistribute or to effect social reforms.

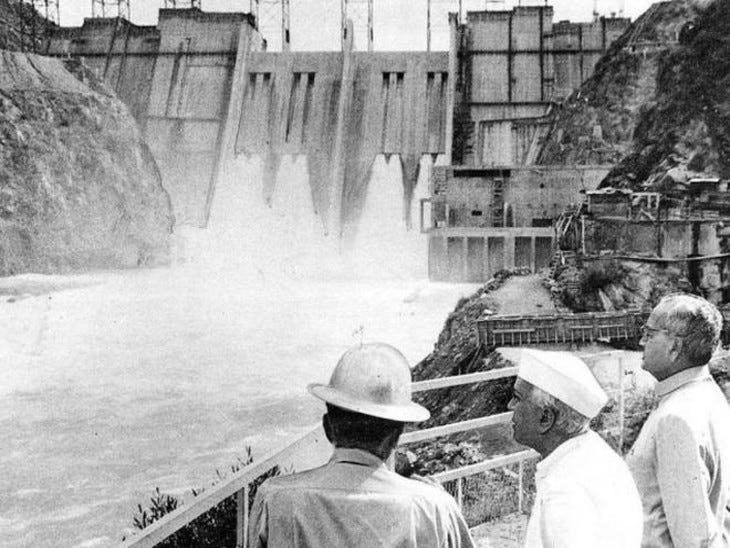

Nehru’s economic thought

Nehru’s economic thinking is commonly traced to an over-impressionable liking for the Soviet model of planned industrialization. Yet this is a crude reading of his purposes and practice. Not merely was Nehru from his very earliest encounters with the Soviet experiment critical of its political consequences; his own practice after 1947 was more improvisatory than ideological, and aimed to unite into a single, coherent strategy quite diverse intentions.

The bright arc of the West’s history illuminated for Nehru a silhouette of India’s future economic possibilities. It encouraged him to believe that an independent India could follow three ends simultaneously: industrialization directed by a state, constitutional democracy, and economic and social redistribution. This project was rather distant from Soviet practice, and much closer to postwar European social democracy. Indeed, by the late 1940s, Nehru had shifted to a recognizably social-democratic position that would not have been out of place in the radical mood of the post-1945 Labour Party.

Nehru proposed a view of the state’s domestic responsibilities that had parallels with Keynesian ideas. The state had actively to create conditions for economic expansion: not through wholesale nationalization, but by investment in and direction of a public sector that would function alongside private enterprise in a mixed economy, acting as a counterweight to the cyclical swings and fashions of private investment. Given the Indian state’s inherited tradition of being a low taxer, and given that constraints on agricultural taxation were enshrined in the new Constitution, if it was going to have any resources to redistribute for welfarist purposes, it would have to generate these through a productive public sector in its own control.

The ancestry of this argument for a public sector is therefore not correctly traced to the Soviet model of a command economy, nor did it derive from an ideological conviction in the virtues of collectivism. Rather, in its redistributive ambitions, it had obvious resonances with the policies adopted in many western European countries in the post-war period.

Nehru on the trade-off between democracy and economic growth

For Nehru, a rapid growth rate was not an end in itself. It had to be reconciled with independence and with democracy. Yet he was equally clear that given the Indian commitment to democratic politics, growth rates in heavy industries could not be forced, in Soviet or Chinese style. In contrast to present-day, instrumentalist attitudes to democracy, which puzzle over whether or not democracy is conducive to economic growth, Nehru assumed that democracy was a value in itself. He did not believe in a trade-off between the two, the ‘cruel choice’ postulated by some economists. Economic development and democracy were intrinsic virtues of the modernity to which he was committed, and both had to be pursued simultaneously. This perhaps obvious point was so elementary to Nehru’s view of economic development that it bears restatement.

Nehru’s dilemma and pressures of routine electoral politics on economic policy

Nehru was thus trapped by what observers variously called a paradox, contradiction or dilemma. His government was observant of the procedures of constitutional democracy and enjoyed democratic legitimacy, based on its nationalist aura and sustained by winning three general elections between 1952 and 1962. It was also dedicated to establishing an independent industrial base and to reformist and redistributive ends. But neither Congress as a whole nor the democratic weight of numbers, controlled in the countryside by those who stood to lose through reform, could be mobilized in support of these commitments. In principle – and after Nehru – in practice, the choice came to be posed simply: either democracy had to be curtailed, and the intellectual, directive model of development pursued more vigorously (one of the supposed rationales offered for the Emergency of the mid-1970s); or democracy had to be maintained along with all its cumbersome constraints, and the ambition of a long-term developmental project abandoned. The striking point about the seventeen years of Nehru’s premiership was his determination to avoid this stark choice. Any swerve from democracy was ruled out; the intellectual arguments had, however, to be upheld. The claims of techne, the need for specialist perspectives on economic development, were lent authority by the creation in 1950 of an agency of economic policy formulation, insulated from the pressures of routine democratic politics: the Planning Commission.

Economic crisis and reforms of 1991

The economic crisis of 1991 came in the midst of political difficulties. India’s electoral politics had moved into a phase of fragmented outcomes and coalition or minority governments, as support for Congress haemorrhaged and split between parties of caste, region and Hindu nationalism. The most sweeping realignment of the state’s relation to the economy was thus initiated by a minority Congress government, the weakest ever to rule the country. At its head was P. V. Narasimha Rao, who succeeded to the party leadership after the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi in May 1991. Few gave Rao – a backroom fixer thrust into the limelight and visibly acting at the behest of international aid donors – much of a chance. But he was to be the first Indian prime minister drawn from outside the Nehru family to remain in office for the duration of his five-year term. The political weakness of the government worked both to his and to the technocrats’ advantage. The Finance Ministry was put in the hands of Manmohan Singh, a distinguished economist who had written a thesis at Oxford in the 1950s on trade policy, and was known to favour a more liberal economic regime. A kind of Mahalanobis for the 1990s, Singh lacked a political constituency, either within or outside Congress; but he had the support of Rao and was the one minister who remained in the same office throughout the tenure of Rao’s government. This temporary reprise of powers by intellectuals and technocrats was now turned to goals quite different from those set in the 1950s.

Wider consensus on economic liberalization

Within India, business and industrial interests as well as some among the political parties had arrived at a disillusioned consensus that state controls of the economy needed to be pruned. The profusion of controls had failed to create a productive public sector, squeezed out private enterprise, and given the state access to resources used not for welfare but as pools of patronage. Some efforts at reduction in controls had been introduced by the Rajiv Gandhi government in 1985, and this had given currency to the idea of economic reform. But in the early 1990s, the most vocal intellectual arguments for liberalization came from abroad – from the ranks of dispersed intellectuals and economists lodged in the international economic agencies and universities. There was no clearer proof of the stunning rise of Indian professional economists since the 1950s: they had become, along with mystics and godmen, India’s best export. Their arguments were directed at the basic design of economic development that, they held, had been adopted in the 1950s.

In the most succinct and pointed statement of the liberalizers’ argument, Jagdish Bhagwati claimed that India’s clever economists of the post-independence years had devised ‘a model that couldn’t’. The problem, as he saw it, lay in India’s rigid pattern of low growth. Its causes lay not in low savings, as had been feared in the 1950s, but in ‘disappointing productivity performance’, with which the planners had been unconcerned. Their model ignored matters of efficiency and focused purely on allocative choices: capital investment was directed towards industries protected from competition. This had required extensive bureaucratic controls, inward-looking trade and foreign investment policies, and the creation of an unwieldy public sector. The result was a ‘control-infested system’ that smothered private initiative and encouraged the proliferation of inefficiencies and corruption within both the state-controlled economy and the political system as a whole. Distrust of the market and faith in central control nurtured misconceived economic policies that were continued because of an obstinate political fixation on ‘Indian socialism’: a doctrine to keep concentration of economic power out of private hands, to protect the small-scale sector such as hand-loomed textile production, and to avoid regional imbalances across the federal system.

Who is an Indian?

Change in the definition of Indianness by 1990s

The truncated colonial territories inherited by the Indian state after 1947 still left it in control of a population of incomparable differences: a multitude of Hindu castes and outcastes, Muslims, Sikhs, Christians, Buddhists, Jains and tribes; speakers of more than a dozen major languages (and thousands of dialects); myriad ethnic and cultural communities. This discordant material was not the stuff of which nation states are made; it suggested no common identity or basis of unity that could be reconciled within a modern state. Nor was there a compelling ideological doctrine or symbol, a ‘socialism’ or an emperor, around which to unite. For a few parenthetic decades after independence, Nehru’s improvised conception of a tolerable, common Indianness seemed to suggest a basis for India’s sense of itself. It was an explicitly political conception, and to sustain itself, it had constantly to persuade. That conception has given way, corroded by more exclusivist ideas of India and of political community. By the 1990s, definitions of Indianness were in fierce contest once again: Hindu nationalists struggled to capture the state and to purge the nationalist imagination, leaving it homogenous, exclusive and Hindu; others fought to escape the Indian state altogether and to create their own smaller, homogenous and equally exclusive communities.

The uncertainties that surrounded definitions of the Indian political community had settled symbolically on the town of Ayodhya, a place with no resonances of colonial humiliation or trace of futuristic monuments, but a stage where a quite different historical drama could be re-enacted. The wrecked site itself poses Indians with a practical dilemma.

Indianness before and after Nehru

The Indianness outlined in the two decades after 1947 was an extemporized performance, trying to hold together divergent considerations and interests. The result was a highly unusual nationalism that resists summary in clear or simple doctrinal statements. It tried to accommodate within the form of a new nation state significant internal diversities; to resist bending to the democratic pressures of religion; and to look outwards. This experimental response to the question of how to be Indian was not a victory of theoretical consistency. It was a contingent acquisition, based on a coherent if disputable picture of India. It did not reassure itself by relying on a settled image of the culture, nor did it try to impose one. That was its most important trait: it did not monopolize or simplify the definition of Indianness. For all the political vexations visited upon it, it could claim success: India, an ungainly, unlikely, inelegant concatenation of differences, after fifty years still exists as a single political unity. This would be unimaginable without Nehru’s improvisation.

Within two decades of Nehru’s death in 1964, India’s layered, plural, political self-definition was in serious difficulties. The extent was apparent from a shift in intellectual climate. India’s Westernized intellectuals, on whose support Nehru could always count, had turned against the state that was acting in his name. The object of their criticism was the elusive notion of secularism. These intellectuals were trying to explain a puzzling fact about India in the 1980s. Four decades after independence and the end of colonialism – which, according to nationalist dogma, had been responsible for ‘communalist’ dissensions – the identities of religion and caste had started to invade national politics with ferocious energy. Why?

To the self-proclaimed ‘Nehruvians’, devotees of the ‘scientific temper’, the fault lay with the society itself, limited in its education and shackled by superstition and obscurantism. Yet fewer and fewer were convinced by this diagnosis. The presence and actions of the state, committed to the project of modernization and ‘nation-building’, seemed to be responsible. Some intellectuals, searching for a sociological explanation, attacked the ambition of trying to create a secular state and a society of liberal individuals. Oddly, they ascribed this project to Nehru. And they saw it as doomed in India: it was, in the words of one of the country’s leading sociologists, ‘the dream of a minority which wants to shape the majority in its own image, which wants to impose its will upon history but lacks the power to do so under a democratically organized polity’. Nehru, a hapless straw man in such ruminations, was condemned both for trying to impose his modernist will upon a society of deep religious belief and for not being Kemalist or Leninist enough to push through his secularist ambitions. Given the extent of religious belief in Indian society and given that India was a democracy, such arguments proceeded, it followed that the religious preferences of the majority should rule in the state: ‘In an open society the state will reflect the character of the society.’ The centrality of religion must be expressed in the Constitution, which should be revised to remove ‘anomalies’ – protective safeguards for communities and regions – in order to produce a uniform, homogenous legal code. Democracy meant, quite simply, the rule of the majority.

More trenchant arguments pointed to the way that secularism had, since Nehru, become an instrumental ideology of the state. It now functioned as a legitimating cloak for the modernist élite, who used it to mask their grip at the very moment when this was being challenged by the surge of mass democracy. The use of secularism as an ideology of state power had engendered a new monster on the political landscape, a Hindu nationalism remotely linked to religion, which merely used it instrumentally to capture state power. Secularism as a doctrine of state was thus responsible for the corrosion of faith in the society. It had instrumentalized and corrupted the capacities for interreligious understanding and social peace which India had possessed in the past. The intellectual argument here resonated with the anti-statism that had animated the thinking of both Tagore and Gandhi; but in the face of the palpable reality of the Indian state, it remained difficult to see what it could imply in practice.

The real ‘idea of India’

India, this historical and political artefact, a contingent and fragile conjunction of interlinked, sometimes irritable cultures, has been since 1947 continuously subject to a common political authority. The notions of territorial integrity and national unity, fundamental to both Hindu and Indian nationalism, are, as in all nationalisms everywhere, ideological fictions, fabulous myths – this applies equally to the Indian Union and the idea of Bharatavarsha. But it also applies to the more fragmentary imaginations of those aspired-for lands, Khalistan or Tamil Eelam, Kashmir or Bodoland. The demands of culture, the claims for recognition, are against large federal states, but the pressures of economics are towards interconnection and expansion of scale. The idea of India has been constituted through struggles to balance these contrary pulls in a coherent political project, to respect the diversities of culture with a commitment to a common enterprise of development.