Dispatch #69: ‘Laws cannot remain silent when the canons roar’- Part 1

In this dispatch, we will explore the idea of constitutionalism, separation of powers, and the Basic Structure doctrine of India

These were the words used by the Supreme Court (SC) of India in the Nandini Sundar & Ors vs State of Chhattisgarh judgment in 2011 while declaring the state’s act of recruiting young poor tribal men for counter-terrorism to tackle Naxal menace in the state as unconstitutional. The petitioners moved the apex court to challenge Chhattisgarh state’s strategy to counter Naxalism in the state by arming young, poor, and illiterate men with guns. They were called the Special Police Officers (SPOs) or the Koya commandos. One should not treat this judgment as trivial. The judiciary, drawing its power from the Constitution, had put shackles on the executive or the elected government. This implies that an unelected institution can put constraints on the elected institution. Laws can trump the democratic will of the people. A group of unelected judges can make the elected government of the day, representing the majoritarian views, stop its act of arming its citizens against other citizens.

The judgment invoked the idea of constitutionalism which is the hallmark of all democratic polities. Constitutionalism is a concept, embedded into the constitution that ‘We the people’ have given to ourselves, where ‘no organ of the state may arrogate to itself powers beyond what is specified in the constitution’.

The judgment says:

We must also bear the discipline, and the rigour of constitutionalism, the essence of which is the accountability of power, whereby the power of the people vested in any organ of the State, and its agents, can only be used for promotion of constitutional values and vision. This case represents a yawning gap between the promise of a principled exercise of power in a constitutional democracy, and the reality of the situation in Chattisgarh, where the Respondent, the State of Chattisgarh, claims that it has a constitutional sanction to perpetrate, indefinitely, a regime of gross violation of human rights in a manner, and by adopting the same modes, as done by Maoist/Naxalite extremists. The State of Chattisgarh also claims that it has the power to arm, with guns, thousands of mostly illiterate or barely literate young men of the tribal tracts, who are appointed as temporary police officers, with little or no training, and even lesser clarity about the chain of command to control the activities of such a force, to fight the battles against alleged Maoist extremists. As we heard more and more about the situation in Chattisgarh, and the justifications being sought to be pressed upon us by the respondents, it began to become clear to us that the respondents were envisioning modes of state action that would seriously undermine constitutional values. This may cause grievous harm to national interests, particularly its goals of assuring human dignity, fraternity amongst groups, and the nation's unity and integrity. Given humanity's collective experience with unchecked power, which becomes its own principle, and its practice its own raison d'etre, resulting in the eventual dehumanization of all the people, the scouring of the earth by the unquenchable thirst for natural resources by imperialist powers, and the horrors of two World Wars, modern constitutionalism posits that no wielder of power should be allowed to claim the right to perpetrate state's violence against anyone, much less its own citizens, unchecked by law, and notions of innate human dignity of every individual. Through the course of these proceedings, as a hazy picture of events and circumstances in some districts of Chattisgarh emerged, we could not but arrive at the conclusion that the respondents were seeking to put us on a course of constitutional actions whereby we would also have to exclaim, at the end of it all: ‘the horror, the horror’.

The idea of Constitutionalism is a counter-majoritarian notion. Constitutionalism is a mechanism or a framework comprising rules or norms that provide checks and balances to the majoritarian tendencies of democracy. It is an idea associated with the limitations provided by either a written proclamation, like a constitution or an arm of the government, to the majoritarian excesses of the state, to safeguard individual rights and liberties. It is a notion under which the function and the decision of the government must comply with the provisions of the Constitution of that country.

Constitutionalism in India has 3 dimensions:

Basic Structure Doctrine

Separation of powers

Judicial review

We will discuss this later. First, we should go a bit deeper into the theoretical aspects of constitutionalism.

The idea of a constitution or a referee institution such as a judiciary putting checks and balances on the executive branch or the legislative branch is not exclusive to India.

In 2006, the Federal Court of Justice in Germany (Bundesgerichtshof) in its press release declared Section 14.3 of the Aviation Security Act incompatible with the Basic Law (Germany’s constitution) and hence void. Section 14.3 of the Aviation Security Act authorised the armed forces to ‘shoot down aircraft that are intended to be used as weapons in crimes against human lives’. The court said that the government cannot take away the lives of its citizens since it takes away the guarantee of human dignity (Article 1.1 of the Basic Law) of the people who are not the participants of the crime.

The press release adds:

The passengers and crew members who are exposed to such a mission are in a desperate situation. They can no longer influence the circumstances of their lives independently from others in a self-determined manner. This makes them objects not only to the perpetrators of the crime. Also, the state which in such a situation resorts to the measure provided by Section 14.3 of the Aviation Security Act treats them as mere objects of its rescue operation for the protection of others. Such a treatment ignores the status of the persons affected as subjects endowed with dignity and inalienable rights. By their killing being used as a means to save others, they are treated as objects and at the same time deprived of their rights; with their lives being disposed of unilaterally by the state, the persons on board the aircraft, who, as victims, are themselves in need of protection, are denied the value which is due to a human being for his or her own sake. In addition, this happens under circumstances in which it cannot be expected that at the moment in which a decision concerning an operation pursuant to Section 14.3 of the Aviation Security Act is taken, there is always a complete picture of the factual situation and that the factual situation can always be assessed correctly then.

Yet again, a law passed by the representatives of the people in parliament was subject to the limit by the judiciary since it violated the German constitution and found it completely inconceivable to kill people who are in a helpless situation. The constitution emerged as the guarantor of rights even though it has to shackle people’s democratic will.

One needs to appreciate the fact that the limits to one organ of the government by the other do not emerge ad-hoc. The constitution provides the separation of powers and checks and balances. A constitution is a ‘set of norms (rules, principles or values) creating, structuring, and possibly defining the limits of, government power or authority’. It’s the constitution that has given birth and legitimacy to the three organs of the state- legislature, executive, and judiciary. Part 5, Chapter 1 talks about the executive; Chapter 2 talks about the Parliament; Chapter 4 talks about the judiciary. Hence, the Constitution acts as the North Star for these institutions and imposes substantive limits to the powers of each other. These limits are of several types: imposing constitutional limits against the government when rights and rule of law are encroached upon; articulating the scope and limits of constitutional changes; scope of authority especially in a federal system.

Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy says this on constitutionalism:

Constitutionalism in this richer sense of the term is the idea that government can/should be limited in its powers and that its authority depends on its observing these limitations.

Now let’s look at what political philosophy has to say on constitutionalism and limits to government power. But first some conceptual clarity.

We will be using two concepts in this section and it is very important to understand their meanings.

Sovereignty is ‘the possession of supreme (and possibly unlimited) normative power and authority over some domain’.

Government is the ‘group of people or institutions through which sovereignty is exercised.’

Therefore, one can conclude that the ultimate sovereignty may not necessarily lie with the government and its institutions. In democracies, sovereignty lies within the people. The people delegate sovereignty to the representatives (or government) to make laws since they themselves can’t take part in day-to-day political decision-making. The government’s authority is however limited by constitutional law. This is the essence of constitutionalism and is seen in all constitutional democracies.

Stanford encyclopedia explains:

Arguably this is what one should say about constitutional democracies where the people’s sovereign authority is thought to be ultimate and unlimited but the government bodies—e.g., legislatures, Presidents, and courts—through whom that sovereignty is exercised on the people’s behalf are constitutionally limited and subordinate. As Locke might have said, unlimited sovereignty remains with the people who have the normative power to void the authority of their government (or some part thereof) if it exceeds its constitutional limitations. Though sovereignty and government are different notions, and normally apply to different entities, it nevertheless seems conceptually possible for them to apply to one and the same individual or institution.

Hence no institution is more powerful than another and it’s the constitution given by ‘We the people’ to ourselves whose authority writ large. Now, the question may also arise that there can be times when ‘We the people’ can change their minds and a big constitutional upheaval happens and the authority of the institutions may also change. In such hypothetical times, constitutional supremacy can be undermined and laws passed by the parliament (like recruiting poor tribal for counter-terrorism or shooting down aircraft with innocent citizens in there) can go unchallenged because after all the representatives, chosen by the majority, have passed those laws. To answer this question we have to see what American constitutional scholar Bruce Ackerman has to say about it. Ackerman introduced a concept called ‘dualist democracy’, which essentially means that in any country law making happens at different times and at different levels. The ‘higher lawmaking’ happens at exceptional levels of national upheaval and churn. During these times there is public mobilization, deliberation, and public debate about issues of constitutional significance. Then there is ‘ordinary lawmaking’ which happens in normal times by majority vote in legislatures. Ackerman argued that the laws created during the higher lawmaking time cannot be changed, even by the citizens, since the mass mobilisation and public debate provided more legitimacy. So, for example, no ordinary law by whatsoever brute majority in parliament can pass a law that changes India’s status from a secular country to a theocratic country. Only mass mobilisation and public debate have the capacity to do that. Therefore, under normal circumstances, people just can’t change their minds and vote for a government that will convert a secular state into a religious theocratic state.

Even the authors of the Federalist Papers (Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay) were apprehensive about accumulating power in one institution. They termed this scenario as a ‘dangerous tendency’. In Paper 47, James Madison advocated the principle of separation of powers as a key principle of constitutionalism. Madison used Montesquieu’s idea of liberty and separation of powers to cement his argument. In Book 11 of The Spirit of Laws, Montesquieu argued that:

When the legislative and executive powers are united in the same person, or in the same body of magistrates, there can be no liberty; because apprehensions may arise, lest the same monarch or senate should enact tyrannical laws, to execute them in a tyrannical manner. Again, there is no liberty, if the judiciary power be not separated from the legislative and executive. Were it joined with the legislative, the life and liberty of the subject would be exposed to arbitrary control; for the judge would be then the legislator. Were it joined to the executive power, the judge might behave with violence and oppression. There would be an end of everything, were the same man or the same body, whether of the nobles or of the people, to exercise those three powers, that of enacting laws, that of executing the public resolutions, and of trying the causes of individuals.

In the Indian Constitution, Article 50 lays out the separation of powers between judiciary and executive. It says ‘The State shall take steps to separate the judiciary from the executive in the public services of the State’.

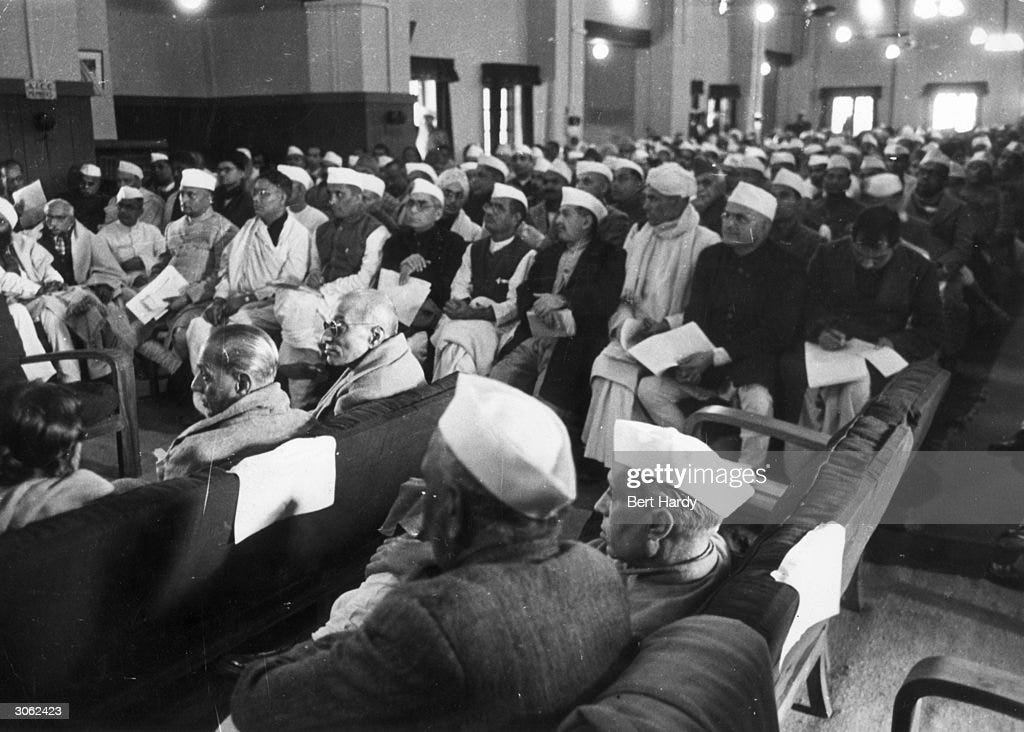

In India, the separation of powers is not very distinct but the different organs of the government are given enough space by the constitutional provisions so that one organ does not seize the function of the other. Prof K T Shah, one of the members of the Constituent Assembly was in favor of the doctrine of separation of powers that would strictly separate the powers of legislature, executive, and judiciary. However, K Hanumanthaiah and Dr. B R Ambedkar dissented from Shah’s proposal.

Dr. Ambedkar argued that:

There is no dispute whatsoever that the executive should be separated from the judiciary. With regard to the separation of the executive from the legislature, it is true that such a separation does exist in the Constitution of the US; but many Americans themselves were quite dissatisfied with the rigid separation embodied in the American constitution between executive and legislature. The work of the Parliament is so complicated that unless and until the members of the legislature receive direct guidance and initiative from the members of the executive, sitting in the Parliament, it would be very difficult for members of Parliament to carry on the work of the legislature.

Later, in the Kesavananda vs State of Kerala judgment in 1973, the Supreme Court made the separation of powers between the three government organs part of the Basic Structure doctrine.

In the next dispatch, we will continue this discussion.