Dispatch #7: It's the economy, stupid?

In this dispatch, we will discuss democratic accountability, the rise of charismatic leaders, Teflon coating and the mood of the nation

In the latest Mood of the Nation 2020 (MOTN) survey conducted by India Today, a whopping 78% of respondents rated the performance of Narendra Modi as Prime Minister as outstanding (30%) and good (48%). These high levels of confidence on the PM are unprecedented and surprising at a time when the country is fighting the global pandemic, there are rising tensions on the national borders and the economy is sluggish and the revival seems to be a long haul.

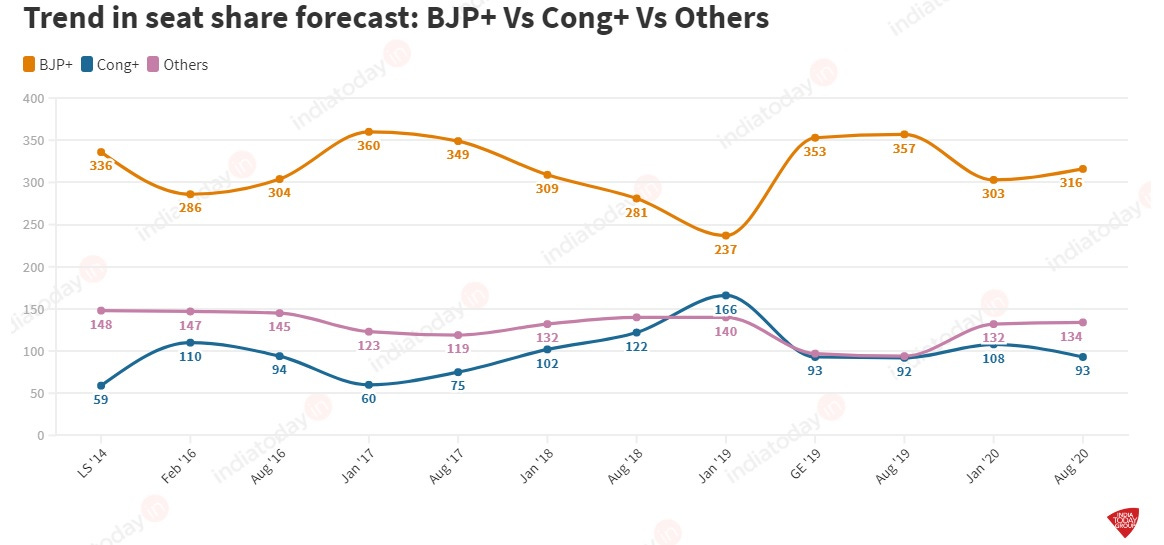

According to the MOTN results, if the elections are held in August 2020, almost a year after the re-election of the BJP, then the BJP and its allies will get 316 seats which are slightly less than what they got in May 2019, but still, they will be in a comfortable majority. The Congress and her allies, on the other hand, will get almost the same number of seats what they got last year, that is 93. Even the vote share for both the parties won’t change. In 2019, the BJP got a 45% vote share while the Congress got 27%. If the elections are held now, the BJP would still get 42% vote share and the Congress would get 27%.

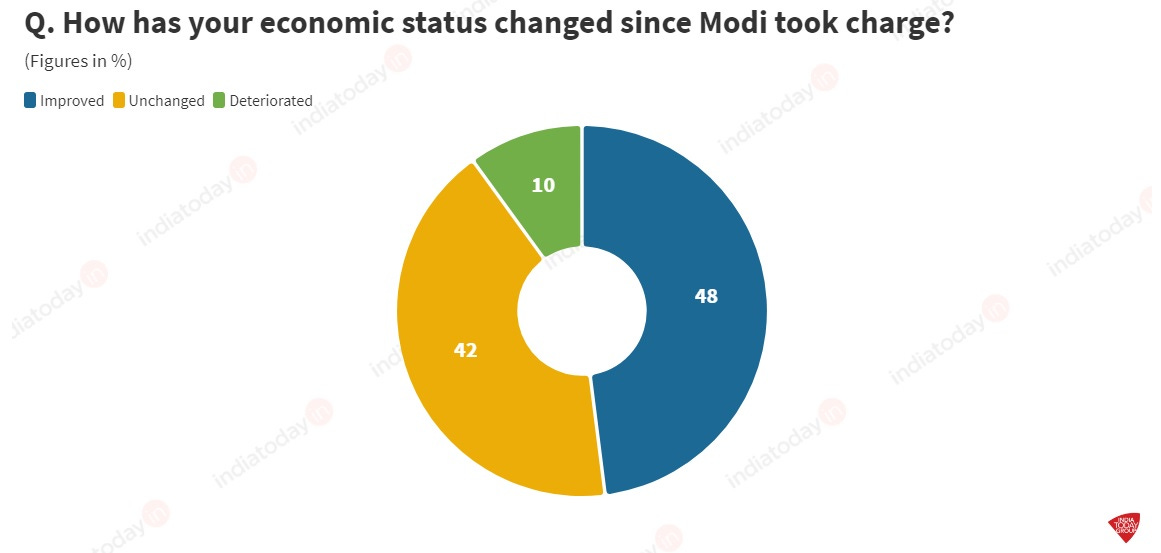

Let’s take a look at another statistic. When asked whether the economic status of the respondents have changed since Modi became the PM, 48% said that it has improved, while 52% either saw no change in the economic status or their economic fortunes has deteriorated.

This is quite counter-intuitive. When the economic status of the citizens are not improving and when the country is facing one of the worst economic and health crisis, there should have been a whiff of anti-incumbency.

Doesn’t good economics make for good politics any more in India? Were there elections that were won on economic growth and development or ‘vikaas’ as they say? And what happened to Bill Clinton’s chief strategist James Carville famous quote ‘It’s the economy, stupid’?

The conventional wisdom is that the voters punish the incumbent political party if it has not been able to perform on the economic front. The 2019 general election was an aberration from this wisdom. The incumbent BJP was up against the wall when the challenger, the Congress, was trying to make slow economic growth, rural crisis and unemployment as electoral issues. We all know the results of the 2019 general elections. The BJP came back to power with a stronger mandate and an increase in the vote share. The economy seemed to be a non-issue for the voters.

Milan Vaishnav and Reedy Swanson, in their 2015 paper, titled ‘Does good economics make for good politics? Evidence from Indian states’ have studied the correlation between the economic growth and the electoral returns of the incumbent party in the state elections. Their analysis shows that in the 1980s and 1990s, there is either a negative correlation or no correlation between the economic growth and the percentage seat and vote share of the incumbent political party. But in the 2000s there is a positive correlation between economic growth and the electoral return of the incumbent party. This essentially means that in the 2000s the voters were kicking out the incumbent government if they were not able to deliver on the economic front.

When we review pooled data from the last three decades of state elections in India’s major states, we find no evidence of a statistically meaningful relationship between growth and electoral performance. At first glance, this seems to support the scholarly consensus that suggests that Indian voters typically focus on personal or parochial issues when deciding whom to vote for rather than broader issues of the economy. However, the picture changes when we look at the dynamic relationship between growth and elections; we find significant electoral returns to governments that deliver higher growth in the post-2000 period. Our results, therefore, lead us to conclude that the Indian voter is increasingly rewarding good economic performance, as a growing body of evidence seems to suggest. In other words, in the current era of Indian politics it appears that good economics can make for good politics.

-Milan Vaishnav and Reedy Swanson, ‘Does good economics make for good politics? Evidence from Indian states’

The authors argue that there could be three reasons behind the positive correlation between economic growth and the shift in voters’ behaviour in the 2000s:

a) Except in the last years of UPA 2, the economic growth of India and the states was high. This could have led to an increase in the aspirations of voters, who would reward the party that could make policy decisions to increase the economic fortunes of the voters. In addition to this, some of the state governments actually did a good job in making sure that every section of the society could reap the dividends of rapid economic growth.

b) The political competition has increased manifolds since the late 1980s and 90s with the rise of the regional parties and political satraps. The voters have an option to ‘exit’ from one political party and support the other because they see their economic fortunes improving in the opposite camp. This left with no other choice for the incumbent political party to deliver on the economic front.

c) The voters realised that it’s the state governments that could lead the efforts on the economic front. Hence they turned out in large numbers during the state elections to make the state governments accountable for the economic growth of the state and their individual economic fortunes.

This trend continued till the 2014 general assembly elections when the voters were angry with the UPA 2 because of corruption and slow economic growth and they wanted a leader who is strong, decisive and who can take decisions that would take India on to a growth trajectory. However, as mentioned above, the 2019 general elections was an exception. Conventional wisdom says that the voters would turn out in large numbers on the voting day to kick out the incumbent government since it failed to deliver on the economic front. Voters did turn out in large numbers in 2019, but only to get the incumbent government back in power amidst the poor performance on the economic front and a 40-year high unemployment rate.

Political scientist Neelanjan Sircar calls this the politics of ‘vishwas’. There was a reason why the BJP made ‘sabka saath, sabka vikas, aur ab sabka vishwas’ their slogan as they fought the 2019 elections. By invoking the term ‘vishwas’, the BJP wanted the voters to trust PM Modi even though things were not looking good. The politics of ‘vishwas’ is personality-driven, people always trust the charismatic leader to make the right decisions and centralisation of power are one of its basic tenets. The politics of ‘vishwas’ is a complete antithesis to democratic accountability. In the democratic accountability polity, voters have a certain set of ideas around their economic well-being and they evaluate incumbent political party on that basis. In the politics of ‘vishwas’, the leader can change the narratives very easily. For example, after demonetisation, that removed 86% of the currency in circulation overnight, we were told that this would curb black money; then we were told that this will curb terrorism that thrives on counterfeit notes; later we were told that this will encourage digital payments and hence would give a boost to Digital India. With RBI’s claim, last year that 99% of demonetised notes have returned to the central bank, we all know that the stated purpose of demonetisation was defeated. Similarly, at the peak of the 2019 election campaign, we were told that the biggest threat to our country is our neighbour and hence we should stop squabbling over the sluggish economic growth and lend support to the PM who is acting tough on Pakistan.

The differences between the politics of vikaas and vishwas structure political and electoral behavior in important ways. In traditional models of democratic accountability, i.e. the politics of vikaas, there is little room the role of the political mobilization and little discussion of what makes voters turn out to the polls. In the politics of vikaas, the voter looks at the choices available to her and selects the candidate or party most likely to deliver economically or closest to her in terms of ideology. These models require that a voter can identify a stable set of issues consistent with their own preferences and have sufficient information on the preferences and attitudes of political actors. In the politics of vishwas, the reverence to a particular politician is explicitly a function of how well the individual politician is able to connect to the voter (or, perhaps, demonize the opponent) – chiefly through media or the strength of party organization.

-Neelanjan Sircar, ‘The politics of vishwas: political mobilization in the 2019 national election’

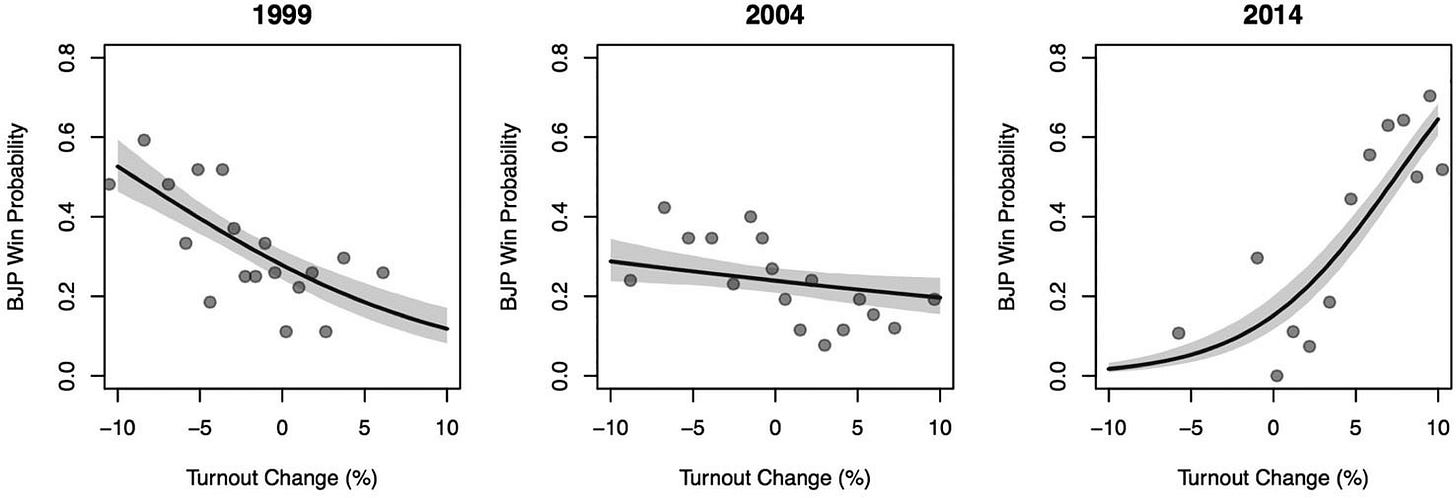

The politics of ‘vishwas’ rests on huge machinery of electoral mobilisation. the BJP has created an election machine over the years because of its cadre and also because it dominates the electoral funding landscape. Neelanjan argues that the electoral mobilisation, increase in voter turnout and politics of ‘vikas’ and ‘vishwas’ are closely related to each other. He has analysed the voter turnout data and the probability of the BJP winning that election.

In 1999 and 2004 elections, when the BJP was the incumbent, the probability of winning would drop with increase in voter turnout. In 1999, it won the elections but in 2004 it lost against the Congress and her allies. In 2014, there was anti-incumbency against the UPA and the voters came out to vote in large numbers to kick the UPA 2 out. This is the politics of ‘vikas’.

In 2019 elections, the voter turn out increased and they voted the BJP back in power with a thumping majority. This is quite contrary to the democratic accountability model logic. At a time when the country is growing through its worst unemployment and rural crisis, the voters should have been harsh on the BJP. This is the politics of ‘vishwas’. The voters trusted the infallible leader who would put their interest before anything else.

The democratic accountability model gets undermined when the political parties are deinstitutionalised, the linkages between the voters and the party ideologies are weak but the linkages between the voters and individuals are personalistic, argue Scott Mainwaring and Mariano Torcal. An example of this personalistic linkages could be the BJP campaign where it urged the voters to vote since each vote to the BJP will be a vote to PM Modi. So it does not matter who your representative is as long as your vote is for the leader.

Another important feature of this brand of politics is that while the credit for the achievement goes to the leader, the responsibility for any failure doesn’t. The leader is capable of deflecting blame and criticism. This has been referred to as the ‘teflon coating’ around the leader. A similar teflon coating has been created around PM Modi. In political marketing terms, there are two types of politicians across the political spectrum- teflon personalities to which nothing sticks and velcro personalities to which everything sticks.

The Teflon personalities are perceived as extroverted and outgoing, characteristics appealing to voters and consequently linked to leadership suitability. These personality traits evoke certain emotional connections and reactions that attract voters.

- Christ'l De Landtsheer , Philippe De Vries & Dieter Vertessen, ‘Political Impression Management

PM Modi’s performance is immune to any criticism or scrutiny because he is no more a political leader but a ‘quasi-religious’ leader, argues researcher Asim Ali in his brilliant article written for The Print.

When you are suffering, you don’t sack the messiah, much like you don’t sack God. You redouble your faith, because God tells you your suffering is for a higher cause, the thorny path towards salvation that only God can lead you to. The one time Modi mentioned the suffering of daily wage workers, he termed it as ‘tapasya’ (penance) —suffering for a higher cause, just like he had described his demonetisation move as “yagna against corruption”. When he extended the first lockdown on 14 April, he used the same spiritually imbued terms, calling for ‘tyag’ (sacrifice) and ‘tapasya’. Gandhi told people that India will achieve freedom through sacrifice and self-purification, which was the basis of satyagraha. Modi tells people he will build a ‘self-reliant nation’ — Atmanirbhar Bharat — on their sacrifices and penance. This is why he began his speech with invocations of India’s ancient greatness. Modi is a messiah in a certain moral universe. In this universe, India was great, then we had “1200 years of slavery”, in his words (which includes the ‘slave mentality of post-Independence period’), until Modi arrived to lead us back to greatness.

-Asim Ali, ‘Modi faces no political costs for suffering he causes. He’s just like Iran’s Ali Khamenei’

Comparing Modi to Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei who is also above any political accountability and has a quasi-religious image, Asim writes:

He ignores the plight of the migrants and the poor because he can’t admit to any faults or weaknesses or oversight. The core of his quasi-religious appeal is that he can never be wrong. Even if you don’t understand his plans, you trust him. In fact, it’s better if you don’t understand his plans because it deepens his mystique, the inaccessible ambiguity that characterise religious leaders. Which is why he is so miserly with actual communication, thriving instead on uplifting sermons. Even when spelling out government plans, Modi prefers alliterations and hands out acronyms to people like chantable mantras. His offerings are not only vague but come with no timeline of delivery. You just have to keep the faith.

-Asim Ali, ‘Modi faces no political costs for suffering he causes. He’s just like Iran’s Ali Khamenei’

In most of the appeals to the citizens, Modi puts the onus on them in the form of their responsibilities. Gone are the days of rights that make you entitled. As citizens, you should be aware of your responsibilities. This has also fed into this teflon coating. Shekhar Gupta goes a step further and has called this a titanium coating which is even stronger than a teflon.

He has perfected a new kind of messaging where he prescribes for you good things: cleanliness, honesty, education, use of technology but places the onus on you to do it for yourself and not set targets for himself you can judge him against. So you have to clean up, use digital cash, learn to use smartphones. He stays silent on any setback. He won’t speak on Kathua but later speak generally about the need to protect our “betis” and reform the “betas.” He won’t speak on Una (Gujarat) but later say, in deep anguish, kill me, but not my Dalit brothers. This distances him from bad news. He is never on a defensive ground. His is forever the moral high ground. Rather than be held accountable, he is creating a cult around himself. Even on demonetisation, a decision as disastrous and irrational as Mao’s war on China’s sparrows, his message has simply been: I know this caused you pain, but aren’t you willing to suffer a little to make India a better country? It’s like the biblical logic of how your suffering shows there is God and you need Him.

-Shekhar Gupta,'Superbrand Narendra Modi: Cast in Titanium, not merely coated with Teflon’

All of this image building, rise of the charismatic leader, deinstitutionalisation of political parties, a ruthless election machine that is backed with the paraphernalia of media and social media has led to the undermining of democratic accountability in India. The mood of the nation is the way it is right now because all of these factors have worked in favour of the PM.

Good Reads:

1) Neelanjan Sircar on Narendra Modi’s politics: ‘Murkier the data, easier it is to control the narrative’: In a recent paper, titled “The Politics of Vishwas: Political Mobilization in the 2019 National Election”, Neelanjan argues that instead of the economic accountability model that has been in use in India to explain voter choices – which says that people reward politicians for development – Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s victory in 2019 represents “a politics of vishwas”, meaning trust, and operates in a very different way.

2) The end of economic voting? Contingency Dilemmas and the Limits of Democratic Accountability: All the while, it is worth asking whether the assumption that voters should reward and punish politicians for economic performance is worth sustaining in the first place, and, if so, whether accountability should be the prime normative standard to guide scholarship in the area of economic voting. Regarding the former question, two arguments can be made against the accountability model. First, the complete or “real” economic voting model simply requires too much of citizens to be of much use. To properly judge the government’s record, citizens ideally should be well informed, unbiased consumers of accurate and plentiful information in an environment of clear and transparent political decision making. Such conditions are unlikely to be met in reality save for a tiny number of citizens. Second, if we stick with accountability as a standard for democratic performance, it probably should not be the only or even most prominent standard for assessing the quality of democracy. After all, the issue of representation is much broader and potentially much more interesting than the simple reward-punishment model. Thus, instead of focusing too narrowly on accountability concerns, perhaps the broader notion of responsiveness, which focuses on the various mechanisms of translating citizen preferences into policy outcomes, offers an alternative.

3) Can turnout numbers tell us if the BJP is likely to be re-elected? The conventional wisdom is a very simple formula: high turnout means anti-incumbency, which is voters coming out in droves to kick out a sitting government. This should conversely suggest that low turnout is a pro-incumbent indicator. Unfortunately, there is no evidence to suggest that this wisdom holds true. In 2018, Milan Vaishnav and Jonathan Guy published a paper in the journal, Studies in Indian Politics, which looked at data from 18 major Indian state elections between 1980 and 2012. “Despite the popularity of the notion that citizens come out to the polls in greater numbers when they are motivated to punish the incumbent government, our analyses of three decades of electoral data uncover no such relationship,” the paper concludes.

4) The electoral consequences of India’s demonetisation: The voters did not reward the party that implemented the banking expansion (the Congress) in the years preceding demonetisation. This may have been due to the fact that the benefits of the banking scheme were gradual, and to our knowledge, this was not something that had been used during political campaigns or publicised. In contrast, demonetisation was very salient to anyone residing in India at the time, in addition to which it had also been clear to citizens that it was the ruling party that was responsible for it.