Dispatch #71: The two Indias

In this dispatch we explore the accurate estimates of genuine Indian middle class & will try to distinguish between Middle India and Middle Class India

“Hum log majority hai, lekin hum logon ko koi khada hi nahi karta hai. Hum log middle-class nahi hain, hum log middle finger class hain”

This is a dialogue from the Amazon Prime series ‘Farzi’ between Sunny (Shahid Kapoor) and his childhood friend Firoz (Bhuvan Arora). A devastated Sunny was lamenting when his love interest ditched him for an upscale New Year party. He was ranting about the daily struggle of an average middle-class man whose life revolves around loans and debts to buy small joys for his family.

While one can disagree with Sunny’s pejorative analogy of the middle class, one cannot deny the daily struggle of an average Indian middle-class family. The colourful metaphor for the middle-class status represents millions of Sunnys’ angst-ridden state of mind, frustration and sense of unfulfilled aspirations.

But who exactly is the middle class? Do we have specific criteria to determine this? Does the Indian middle-class influence policymaking? Is there an intricate relationship between the rise of the Indian middle class and India’s growth story?

These were the questions that I set for myself before getting immersed in the latest facts and literature on the Indian middle class.

First, let’s talk about the numerical estimates of the middle class in India.

In a recent article, Rama Bijapurkar and Yuwa Hedrick Wong, have succinctly argued that the middle-class estimates are mostly flawed since they suffer from a ‘lack of clarity on what characteristics the middle class must have in order to qualify the labels’. The result of this flawed approach, add the authors, is ‘several groupings of heterogeneous households all labelled middle class, based on other country benchmarks or subjective judgements with very wide income ranges or yardsticks of consumption of consumer durables, or a magic number of income where consumption is supposed to take-off based on developed world cost structures.

In a paper titled ‘Rise of the Indian middle class and its Impact on the labour market’, authors Andres Eggimann and Michael Jan Kendzia have enlisted all the definitions and the criteria which scholars have been using to estimate the size of the Indian middle class.

Before we move to the consensus on the exact size of the middle class, it is important to note its relevance to the Indian economy since it is the critical driver for ‘economic development through human capital development, consumption and savings.’

According to their calculations, Bijapurkar and Wong argue that ‘India’s genuine middle class is less than half of the 400- 500 million numbers that float around.’ In fact, the Indian middle class is much smaller than the popular estimates and if one uses other criteria, as proposed by the authors, then the middle class in India ‘sits in the richest 10% to 20% of Indian households and not in the middle of the spectrum.’ Bijapurkar, in another article, argues that this narrow section that we are calling the genuine middle class of India can also be labelled as the ‘consumer class’, which essentially means ‘households that have enough discretionary spending power to be interested in goods and services that are commonly associated with the middle class in developed countries.’

The broad criteria, according to Bijapurkar and Wong, to describe the middle class are:

Should have a stable and resilient quantum of consumption

Should have substantial surpluses after the routine expenditure

Ability to bounce back from economic downturns without contracting the consumption

It is this stable and resilient demand that gives investors an incentive to invest which creates a virtuous cycle of jobs, prosperity and growth of the middle class. The surplus income, on the other hand, creates savings. In addition to stable consumption and savings, there must be enabling conditions that lead to an increase in income levels which in turn leads to better-quality consumption. Quality consumption essentially means that the consumption behaviour ‘shifts upwards from price sensitivity to benefit sensitivity'.

If we use the above-mentioned criteria, then the genuine middle class in India is much smaller than what we think. According to Bijapurkar and Young, the Indian middle class is just the richest 10% and 20% of Indian households (D10 and D9 deciles) and not the middle-income groups.

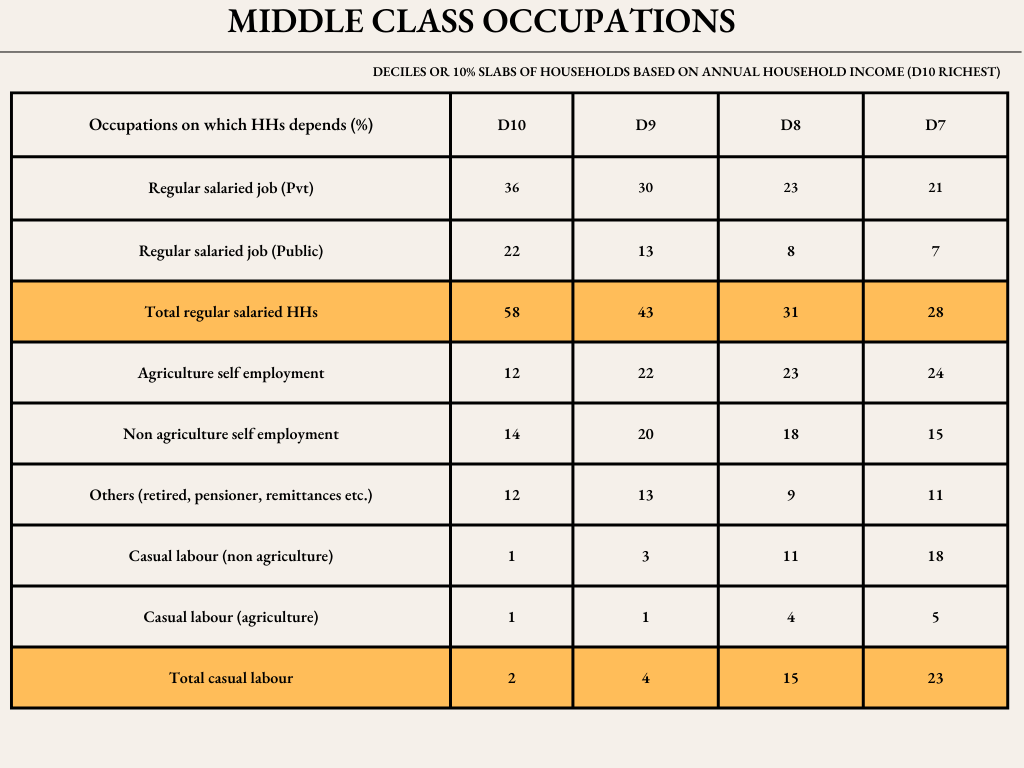

The occupation profile of the genuine middle class (D10 and D9 deciles) shows some very interesting (or rather troubling) trends:

Just 58% of D10 households and 43% of D9 have regular salaried jobs. Imagine such a trend among the richest deciles. Needless to say that this percentage will be lower among the upper middle class and middle class (D8, D7 and D6)

Most of the salaried jobs are contributed by the private sector. Since most of the jobs are informal ones, a big proportion of regular salaries from the private sector are actually coming from the informal sector

Incomes from self-employment, both in agriculture and non-agriculture sectors, are 26% and 42% for D10 and D9 deciles respectively. This implies that a significant proportion of self-employed jobs among the richest households in India are actually precarious

The authors argue:

India is still quite some way off from having a genuine middle class that can power its economy. In an earlier paper titled ‘India’s future lies in building a genuine middle class’, we have pointed out that Middle India, the middle 60% of households in the middle of the income spectrum should have been the genuine middle class of India and has been neglected and that India’s future lies in building a genuine middle-class several times larger than it is now.

So, looking at the stability and resilience of consumption and the ability to have an income surplus, we now know that the genuine middle class is actually not at the middle of the income spectrum, but they are somewhere in the top 20% of households. Wong, in the 2021 paper titled ‘India’s future lies in building a genuine middle class’, argued that there are three Indias if one clubs the income deciles into 3 broad categories:

Rich India

Top 20% of households by income

Includes the consumer class

Average household income= Rs 3,94,271

Middle India

Middle 60% of households by income

164 million households

Average household income= Rs 1,51,651

70% live in rural areas

69% say that they meet basic needs with difficulty

Only saves 7.7% of household income

Poor India

Bottom 20% of households by income

Average annual household income Rs 80,529

Please note that 60% of Indian households, whose average annual income is Rs 1,51,651 is Middle India and not the middle class.

Wong explains:

The sustainability and eventual success of India’s takeoff will depend on an expanding and increasingly prosperous middle class. However, what is commonly referred to as the middle class in India has nothing to do with Middle India, the households located in the middle 60% of income spectrum.

The report concludes that better infrastructure, more formal jobs and gender equality will help expand the middle class, which will boost domestic demand leading to India’s accelerated growth.

These steps ‘would kickstart a virtuous cycle that would create new economic opportunities for all of India.’

On how to transform middle India into a genuine middle class, Wong writes in the report:

Transforming middle India into nation’s genuine middle class would fundamentally support the government’s ambitious efforts to boost GDP growth rates to 8-10% range. With faster growth in household income in middle India, domestic demand would become stronger more quickly. This inturn would open up new opportunities for more productive business investment targeting the domestic market.

While the middle class has been the prime beneficiary of economic liberalisation in the last 30 years, a big section of Indian households (60%) that form Middle India has been neglected.

When Alexis de Tocqueville visited America in the 19th century, he was surprised to observe that the prosperity and upward mobility of American society was driven by its middle class. Even Marx’s prognosis about the bourgeoisie class echoed that of Tocqueville. For Marx, the bourgeoisie class broke the feudal relationships of the individuals ‘not only [to] transform the economic processes and structure of the society, but [also] reshape its politics and fundamentally rework the structure of values that dominates in the society’. While the burgeoning middle class leads to economic growth, there’s a body of work which argues that the middle class plays a critical role in the mainstay and diffusion of democracy.

We will explore the political aspirations and implications of the middle class, its impact on the labour market and the consumption patterns in subsequent dispatches.