Dispatch #73: India, that is Bharat, shall be a Union of States (Part 1)

Excerpts from the Constituent Assembly Debates on Article 1

Article 1 of the Indian Constitution is on the name and territory of the Union and it states that:

(1) India, that is Bharat, shall be a Union of States.

(2) The States and the territories thereof shall be as specified in the First Schedule.

(3) The territory of India shall comprise —

(a) the territories of the States;

(b) the Union territories specified in the First Schedule; and

(c) such other territories as may be acquired.

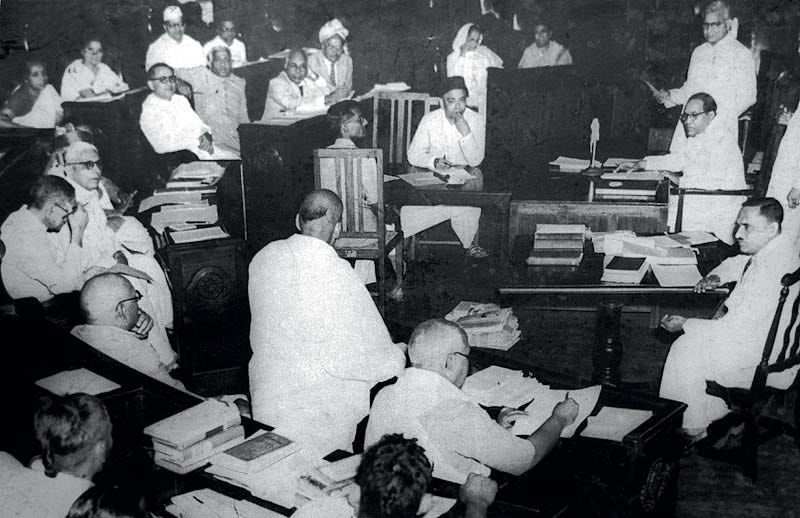

The article was debated on 15th November and 17th November in 1948 and again on 17th September and 18th September in 1949. Several Constituent Assembly members objected to the phrase ‘Union of States’. They suggested that the correct phrase should be ‘Federation of States’. Hasrat Mohani went on to say:

I want to submit that this is a very important article. It does not want only the name, but it also says that it will be a Union of States. This is very objectionable. I have given notice of an amendment on which I will take at least half an hour to explain. I am opposed to this Union of States. I do not want a Union of that kind. Because, originally we had republics. We have given up that idea of republics and we have brought in the States. This is a very serious matter. It cannot be disposed of in a simple manner. I spoke to Dr. Ambedkar; he says he will finish in five minutes. He cannot do that. This is a very serious matter and in this connection I have tabled amendments from the very beginning.

Dr Ambedkar responded by saying that the usage of Union was deliberate and to make sure that the States had no right to secede from India. He explained:

The Drafting Committee wanted to make it clear that though India was to be a federation, the Federation was not the result of an agreement by the States to join in a Federation and that the Federation not being the result of an agreement no State has the right to secede from it. The Federation is a Union because it is indestructible. Though the country and the people may be divided into different States for convenience of administration the country is one integral whole, its people a single people living under a single imperiumderived from a single source. The Americans had to wage a civil war to establish that the States have no right of secession and that their Federation was indestructible. The Drafting Committee thought that it was better to make it clear at the outset rather than to leave it to speculation or to dispute.

Amendments were moved by the Constituent Assembly members to change the name India. M.A. Ayyangar wanted to change the name from India to Bharat. Lokanath Misra was of the opinion that Bharatavarsha was more appropriate. H V Kamath introduced an amendment to keep both Bharat and India in the Draft article. Kamath found the phrase ‘India, that is Bharat’ to be ‘clumsy’. He added:

I only wish to refer to the Irish Constitution which was adopted twelve years ago. There the construction of the sentence is different from what has been proposed in clause (1) of this article. I feel that the expression “India, that is, Bharat”-I suppose it means “India, that is to say, Bharat”-I feel that in a Constitution it is somewhat clumsy; it would be much better if this expression, this construction were modified in a constitutionally more acceptable form and may I say, in a more aesthetic form and definitely in a more correct form.

On 17th September 1949, Dr Ambedkar who was also the Chairman of the Drafting Committee introduced an amendment to the draft article. He told the assembly that:

Sir, I move :

That for clauses (1) and (2) of article 1, the following clauses be substituted:-

(1) India, that is, Bharat shall be a Union of States.

(2) The States and the territories thereof shall be the States and their territories for the time being specified in Parts I, II and III of the First Schedule

The assembly rejected all other amendments to the draft article except one introduced by Dr Ambedkar. Hence Article 1 begins with ‘India, that is Bharat, shall be a Union of States’.

The debates in the Constituent Assembly on 15th October, 17th October & 4th November in 1948, and 17th September & 18th September in 1949 are very critical to understand the evolution of Article 1 of the Indian Constitution.

Here are the excerpts.

15th October, 1948

Ananthasayanam Ayyangar: Sir, I submit that amendments Nos. 83 to 96, both inclusive, may kindly be allowed to stand over. They relate to the alternative names, or rather the substitution of names – BHARAT, BHARAT VARSHA, HINDUSTAN – for the word INDIA, in Article 1, clause (1).

Ananthasayanam Ayyangar: It requires some consideration. Through you, I am requesting the Assembly to kindly pass over these items and allow these amendments to stand over for some time. A few days later when we come to the Preamble these amendments might be then taken up. I am referring to amendments Nos. 83 to 96, both inclusive and also amendment No. 97 which reads:

“That in clause (1) of article 1, for the word ‘India’ the word ‘Bharat (India)’ and for the word ‘States’ the word’ Provinces’ be substituted.”

Vice-President: Is that agreed to by the House?

Yes.

Lokanath Misra: Of course, I would have no objection, Sir, if you defer consideration of these amendments for two or three days, but I beg to bring to your notice that amendment No. 85, which stands in my name, does not only mean to change the name of India into ‘Bharatavarsha’, but it means something more and I am afraid if you hold over this amendment those things would be inappropriate at a later stage. I am submitting that I may be allowed to move this amendment, of course without committing myself to the change of the name of India to ‘Bharatavarsha’ or otherwise. Though I am not insisting on the change of name just now, I ask that I may be allowed to move the other part of my amendment.

K. T. Shah: Sir, I beg to move:

“That in clause (1) of article 1, after the words ‘shall be a’ the words ‘Secular, Federal Socialist’ be inserted.”and the amended article or clause will read as follows:

“India shall be a Secular, Federal, Socialist Union of States.”

K. T. Shah: In submitting this motion to the House I want first of all to point out that owing to the arrangements by which the Preamble is not considered at this moment, it is a little difficult for those who would like to embody their hopes and aspirations in the Constitution to give expression to them by making amendments of specific clauses which necessarily are restricted in the legal technique as we all know. Had it been possible to consider the governing ideals, so to say, which are embodied in this Preamble to the Draft Constitution, it might have been easier to consider these proposals not only on their own merits but also as following from such ideals embodied in the preamble as may have been accepted.

K. T. Shah: As it is, in suggesting this amendment, I am anxious to point out that this is not only a statement of fact as it exists, but also embodies an aspiration which it is hoped will be soon realized. The amendment tries to add three words to the descriptions of our State or Union: that is to say, the new Union shall be a Federal, Secular, Socialist Union of States. The Draft Constitution, may I add in passing, has rendered our task very difficult by omitting a section on definitions, so that terms like “States” are used in a variety of meanings from Article to Article, and therefore it is not always easy to distinguish between the various senses in which, and sometimes conflicting senses in which one and the same term is used. I take it, however, that in the present context the word “Union” stands for the composite aggregate of States, a new State by itself, which has to be according to my amendment a Federal, Secular Socialist State.

K. T. Shah: Take first the word ‘Federal’. This word implies that this is a Union which however is not a Unitary State, in as much as the component or Constituent parts, also described as States in the Draft Constitution, are equally parts and members of the Union, which have definite rights, definite powers and functions, not necessarily overlapping, often however concurrent with the powers and functions assigned to the Union or to the Federal Government. Accordingly, it is necessary in my opinion to guard against any misapprehension or misdescription hereafter of this new State, the Union, which we shall describe as the Union of India.

K. T. Shah: Lest the term ‘Union’ should lead anyone to imagine that it is a unitary Government I should like to make it clear, in the very first article, the first clause of that article, that it is a `federal union’. By its very nature the term ‘federal’ implies an agreed association on equal terms of the states forming part of the Federation. It would be no federation, I submit, there would be no real equality of status, if there is discrimination or differentiation between one member and another and the Union will not be strengthened, I venture to submit, in proportion as there are member States which are weaker in comparison to other States. If some members are less powerful than others, the strength of the Union, I venture to submit, will depend not upon the strongest member of it, but be limited by the weakest member. There will therefore have to be equality of status, powers and functions as between the several members, which I wish to ensure by this amendment by adding the word `Federal’.

K. T. Shah: So far as I remember, this word does not occur anywhere in the constitution to describe this new State of India as a Federation and this seems to me the best place to add this word, so as to leave no room for mistake or misunderstanding hereafter.

K. T. Shah: Next, as regards the Secular character of the State, we have been told time and again from every platform, that ours is a secular State. If that is true, if that holds good, I do not see why the term could not be added or inserted in the constitution itself, once again, to guard against any possibility of misunderstanding or misapprehension. The term` secular’, I agree, does not find a place necessarily in constitutions on which ours seems to have been modelled. But every constitution is framed in the background of the people concerned. The mere fact, therefore, that such description is not formally or specifically adopted to distinguish one state from another, or to emphasise the character of our state is no reason, in my opinion, why we should not insert now at this hour when we are making our constitution, this very clear and emphatic description of that State.

K. T. Shah: The secularity of the state must be stressed in view not only of the unhappy experiences we had last year and in the years before and the excesses to which, in the name of religion, communalism or sectarianism can go, but I intend also to emphasis by this description the character and nature of the state which we are constituting today, which would ensure to all its peoples, all its citizens that in all matters relating to the governance of the country and dealings between man and man and dealings between citizen and Government, the consideration that will actuate will be the objective realities of the situation, the material factors that condition our being, our living and our acting. For that purpose and in that connection no extraneous considerations or authority will be allowed to interfere, so that the relations between man and man, the relation of the citizen to the state, and the relations of the states inner se may not be influenced by those other considerations which will result in injustice or inequality as between the several citizens that constitute the people of India.

K. T. Shah: And last is the term `socialist’. I am fully aware that it would not be quite a correct description of the state today in India to call it a Socialist Union. I am afraid it is anything but Socialist so far. But I do not see any reason why we should not insert here an aspiration, which I trust many in this House share with me, that if not today, soon thereafter, the character and composition of the State will change, change so radically, so satisfactorily and effectively that the country would become a truly Socialist Union of States.

K. T. Shah: The term `socialist’ is, I know, frightening to a number of people, who do not examine its implications, or would not understand the meaning of the term and all that it stands for. They merely consider the term `socialist’ as synonymous with abuse, if one were using some such term, and therefore by the very sound, by the very name of it they get frightened and are prepared to oppose it. I know that a person who advocates socialism, or who is a declared or professed socialist is to them taboo, and therefore not even worth a moment’s consideration……

K. T. Shah: By the term `socialist’ I may assure my friends here that what is implied or conveyed by this amendment is a state in which equal justice and equal opportunity for everybody is assured, in which everyone is expected to contribute by his labour, by his intelligence, and by his work all that he can to the maximum capacity, and everyone would be assured of getting all that he needs and all that he wants for maintaining a decent civilised standard of existence.

K. T. Shah: I am sure this can be achieved without any violation of peaceful and orderly progress. I am sure that there is no need to fear the implications of this term the possibility of a violent revolution resulting in the disestablishment of vested interests. Those who recognise the essential justice in this term, those who think with me that socialism is not only the coming order of the day, but is the only order in which justice between man and man can be assured, is the only order in which privileges of class exclusiveness property for exploiting elements can be dispensed with must support me in this amendment. It is the only order in which, man would be restored to his natural right and enjoy equal opportunities and his life no longer regulated by artificial barriers, customs, conventions, laws and decrees that man has imposed on himself and his fellows in defence of vested interests. If this ideal is accepted I do not see that there is anything objectionable in inserting this epithet or designation or description in this article, and calling our Union a Socialist Union of States.

K. T. Shah: I have one more word to add. As I said at the very beginning this is not merely an addition or amendment to correct legal technicality, or make a factual change, but an aspiration and also a description of present facts. There are the words “shall be” in the draft itself. I therefore take my stand on the term “shall be”, and read in them a promise and hope which I wish to amplify and definitise. I trust the majority, if not all the members of this House, will share with me.

B. R. Ambedkar: Mr. Vice-President Sir, I regret that I cannot accept the amendment of Prof. K. T. Shah. My objections, stated briefly are two. In the first place the Constitution, as I stated in my opening speech in support of the motion I made before the House, is merely a mechanism for the purpose of regulating the work of the various organs of the State. It is not a mechanism whereby particular members or particular parties are installed in office. What should be the policy of the State, how the Society should be organised in its social and economic side are matters which must be decided by the people themselves according to time and circumstances. It cannot be laid down in the Constitution itself, because that is destroying democracy altogether. If you state in the Constitution that the social organisation of the State shall take a particular form, you are, in my judgment, taking away the liberty of the people to decide what should be the social organisation in which they wish to live. It is perfectly possible today, for the majority people to hold that the socialist organisation of society is better than the capitalist organisation of society. But it would be perfectly possible for thinking people to devise some other form of social organisation which might be better than the socialist organisation of today or of tomorrow. I do not see therefore why the Constitution should tie down the people to live in a particular form and not leave it to the people themselves to decide it for themselves. This is one reason why the amendment should be opposed.

B. R. Ambedkar: The second reason is that the amendment is purely superfluous. My Honourable friend,Prof. Shah, does not seem to have taken into account the fact that apart from the Fundamental Rights, which we have embodied in the Constitution, we have also introduced other sections which deal with directive principles of state policy. If my honourable friend were to read the Articles contained in Part IV, he will find that both the Legislature as well as the Executive have been placed by this Constitution under certain definite obligations as to the form of their policy. Now, to read only Article 31, which deals with this matter: It says:

“The State shall, in particular, direct its policy towards securing —

(i) that the citizens, men and women equally, have the right to an adequate means of livelihood;

(ii) that the ownership and control of the material resources of the community are so distributed as best to sub serve the common good;

(iii) that the operation of the economic system does not result in the concentration of wealth and means of production to the common detriment;

(iv) that there is equal pay for equal work for both men and women;….”

B. R. Ambedkar: There are some other items more or less in the same strain. What I would like to ask Professor Shah is this: If these directive principles to which I have drawn attention are not socialistic in their direction and in their content, I fail to understand what more socialism can be.

H. V. Kamath: Mr. Vice-President, the amendment moved by my honourable friend, Prof. K. T. Shah is, I submit somewhat out of place. As regards the words `secular and socialist’ suggested by him I personally think that they should find a place, if at all only in the Preamble. If you refer to the title of this Part, it says, `Union and its Territory and jurisdiction’. Therefore this Part deals with Territory and the jurisdiction of the Union and not with what is going to be the character of the future Constitutional structure.

H. V. Kamath: As regards the word `Union’ if Prof. Shah had referred to the footnote on page 2 of the draft Constitution, he would have found that “The Committee considers that following the language of the Preamble to the British North America Act,1867, it would not be inappropriate to describe India as a Union although its Constitution may be federal in structure”. I have the Constitution of British North America before me. Therein it is said: “Whereas the provinces of Canada, Nova Scotia, have expressed a desire to be federally united”, but subsequently the word “federal” is dropped, and only the word “Union” retained. Similarly, in our Constitution the emphasis should be on the word `Union’ rather than on the word `Federal’. The tendency to disintegrate in our body politic has been rampant since the dawn of history and if this tendency is to be curbed the word `federal’ should be omitted from this Article.

H. V. Kamath: You might remember, Sir, that the content of Federation has been incorporated in the Constitution and we have various Lists prescribed for Union, etc. So long as the essence is there in the Constitution, I do not see any reason why the word `Federal’ should be specifically inserted here to qualify the word `Union’. I therefore oppose the amendment of Professor Shah.

Vice-President: The question is:

“That in clause (1) of Article 1 after the words `shall be a’ the words `Secular, Federal, Socialist’ be inserted.”

The motion was negatived.

H V Kamath on the second part of his amendment.

H. V. Kamath: At the outset, may I bring to your notice, Sir, that I originally sent this amendment separately as two amendments. Unfortunately, the office has lumped them together into one. Had these amendments been printed separately, no difficulty would have arisen. The first amendment was to insert the word “Federal” before the word “Union”, and the second was to substitute the word “Pradeshas” for the word “States”.

H. V. Kamath: May I now proceed to the amendment itself. The second part of the amendment only is before the House. I move, Sir:

“That for the word `States’ in clause (1) of Article 1,the words `Pradeshas’ may be substituted.”

C. Subramaniam: On a point of order, Sir. This is not an amendment. The word “Pradeshas” is only a Hindi translation of the word “States”. If we accept translations of words as amendments, it will create endless complications. The Draft Constitution is in the English language and we should adhere to English terminology and not accept other words, whether they be from Hindi or Hindustani.

Vice-President: May I point out that it is not really a point of order, but an argument against the use of the word “Pradeshas”? Please allow Mr.Kamath, if he so wishes, to address the House.

H. V. Kamath: I am glad, Sir, that several friends have already made their observations because that shows how much interest the House is taking in this matter. So I now proceed fortified by that conviction. My reasons for the substitution of the word “State” by the word “Pradesha” are manifold. Firstly, I find that in this Draft Constitution, the word “State” has been used in more senses than one. May I invite your attention and the attention of the House to Part III, Article 7, of India and the Government and the Legislature of each of the States and all local or other authorities within the territory of India. Here we use the word “State” in quite a different sense. So the first reason for my amendment for the substitution of the word “State” by the word “Pradesha” is to avoid this confusion which is likely to arise by the use of the word “State” in different places in different senses in this Constitution. Secondly, Sir, – I hope my suspicion or my doubt is wrong, – but I feel that this word “State” smacks of a blind copying or imitation of the word “State” which you find in the Constitution of the United States. We have been told by Dr.Ambedkar in his first speech on the motion for the consideration of the Draft Constitution that we have borrowed so many things from various constitutions of the world. Here it strikes me that word “State” has been borrowed from the Constitution of the U.S.A. and I am against all blind copying or blind imitation. Thirdly, Sir, looking at our own history, at least during the last 150 years, the word “State” has come to be associated with something which we intensely dislike, if not abhor. The States in India have been associated with a particular type of administration which we are anxious to terminate with the least possible delay and we have already done so under the sagacious leadership of Sardar Patel. Therefore, this malodorous association with the British regime, which, happily, is no more, I seek to get rid of through this amendment which I have moved before the House. To those friends of mine, who are sticklers for the English language, who think that because this Constitution has been drafted in English, we should not bring in words that are our own, I should like to make one submission and that is this, that the bar to my mind is not against all words that are indigenous, that are Hindi or Indian in their etymological structure. I am reading from the “Constitutional Precedents”, regarding the Constitution of the Irish Free State – it was adopted in 1937 – which was supplied to us a year and half ago by the Secretariat of the Assembly. If we turn to 114 of these Constitutional Precedents, we find there is a footnote on this effect.

“Also in the Irish language.”

H. V. Kamath: This means that the Constitution of 1937 was adopted firstly in English because the footnote says it was adopted also in the Irish language. That means that originally it was adopted in the English language and later on adopted in the Irish language. If you look at the Constitution of Ireland, we find so many Irish words and not English words, words like – I do not know how they are pronounced in the English language – Oireachtas, DailEireann, Taois each (for the Prime Minister) and SeanadEireann. All these words are purely Irish words and they have retained these words in the Irish Constitution adopted in the English language, and they did not bother to substitute the equivalent words in the English language. Therefore it is for this House to decide what words we can incorporate into our Constitution whether they are Indian, Hindi or any other language of our country.

H. V. Kamath: So, Sir, for the reasons that I have stated already the word “State” should never be used in our Constitution in this context. Firstly, because it smacks of blind imitation.Secondly, because of its association with a regime which, by our efforts and by the grace of God, we have put an end to. I will make one other submission, Sir. In the new integrated States – former States or Indian States which we have been able to unite into one unit – we have already used the word “Pradesh”, and we have called the Himachal Union as the Himachal Pradesh and the Vindhya Union as the Vidhya Pradesh, and there is a movement afoot in Assam to call the union of States there as Purbachal Pradesh.

H. V. Kamath: Another point is that we are going to constitute provinces on a new basis in the near future. Already the provinces of Madras, of C. P. and of Bombay have got merged in some of the former Indian States and so the new provinces are going to be different from the old Provinces and therefore the word “Pradesh” is much better and much more apt than the word “State”.

H. V. Kamath: Sir, the last point that I want to make is this. My friend Mr. G. S. Gupta has also tabled an amendment to this article. That would arise only if my amendment is adopted. If this fails, the amendment of my friend will not arise. If my amendment is adopted, then certainly consequential changes will have to be made throughout the text of the Draft Constitution.

H. V. Kamath: Therefore, I move this amendment, Sir:

“That in clause (1) of Article 1, for the word `States’ the word `Pradeshas’ be substituted.”

Ghanashyam Singh Gupta: Sir, I would like to submit this with regard to my amendment. Mr.Kamath has given an amendment which only says that in clause (1) of article 1 for the word ‘States’, the word `Pradeshas’ be substituted. That would mean, that in other clauses, in other articles, the word may not be substituted. If that contingency arises, it may not be all right. Therefore, my amendment No. 104 may either be treated as an amendment to Mr.Kamath’s amendment or I may be allowed to move it now, so that no further complication may arise. Because, it would be really absurd if the word ‘ States’ is changed into `Pradeshas’ only in clause (1) of Article 1. Sir, I shall read Article 1. Clause (1) of Article I say: “India shall be a Union of States.” This is the only place where Mr.Kamath has sought to change. It means instead of `States’ we shall have, “India shall be a Union of Pradeshas.” In clauses (2) and (3) and in other clauses, the word `State’ will continue.

Vice-President: May I interrupt with your permission. If this amendment of Mr.Kamath is rejected, then, amendment No. 104 comes in. Even if it is carried, then, your amendment will come in subsequently and you will have a subsequent chance. I think that would economise the time of the House.

Ghanashyam Singh Gupta: Sir, the procedure that I suggest would really economise the time of the House. If I move my amendment as an amendment to Mr.Kamath’s amendment, the time of the House will be saved. Otherwise, a contingency may arise – I do not say it will. Suppose Mr Kamath’s amendment is carried and mine is rejected…….

Ghanashyam Singh Gupta: Sir, I move:

“That in Article 1 for the word `State’ whenever it occurs, the word `Pradesh’ be substituted and consequential changes be made throughout the Draft Constitution.”

The reason why I want to make this motion just now is what I have already submitted. If Mr.Kamath’s amendment is carried, then it will mean that only clause (1) of Article 1 will be amended, and the rest of it will not be amended. But, if my amendment is carried, then, not only in clause (1) of Article 1 we shall have substituted the word `Pradesh’ for the word `State’, but in the subsequent portions of Article 1 and throughout the Draft Constitution, wherever the word `State’ occurs, so that it would be quite consistent. Otherwise, there would be some absurdity left. The reason why I want the word `States’ in Parts I and II are really provinces and the States in Part III are what are called Indian States at present, none of which are States in the accepted sense of the term. One reason for using the word `State’ may be to synchronise the two, and the other reason could be to follow the American Constitution. The American Constitution has no parallel with us, because, originally the American States were all sovereign States. Our provinces are not at all sovereign; they were never sovereign States. Our provinces are not at all sovereign; they were never sovereign of the Centre. The Indian States also are not sovereign. We want that India should not only be one nation, but it should really be one State. Therefore, I submit that it should be, “India shall be a union of Pradeshas.” I avoid the word ‘provinces’ because it will not fit in with what are now called Indian States, we want that both may be synchronised. This word `Pradesha’ can suit both the provinces and what are now called Indian States. Indian States are merging and merging very fast, thanks to our leaders. Moreover they themselves are choosing that word. For instance, they call Himachal Pradesh, and Vindhya Pradesh. If we use this word for our Provinces as well as for the States, all anomalies would be removed. This is all that I have to say.

K Hanumanthaiah: Sir, I have regretfully to oppose that amendments moved by friends Mr.Kamath and Mr. Gupta. I have to state that by whatever name the rose is called, it smells sweet. Here, the Drafting Committee has advisedly called India a Union of States. My friends want to call the same by the name of a Union of Pradeshas. I do not want this occasion should be utilised for any language controversy. I would appeal to the House not to take this question in that light. The word Pradesh, as admitted on all hands, is not an English word. We are considering the Draft in the English language. I would respectfully appeal to my honourable friends who have moved the amendments to show me in any English Dictionary the word Pradesh. We cannot go on adding to the English language unilaterally all the words that we think suitable. The English language has got its own words. We cannot make the Draft Constitution a hotchpotch of words of different languages. Besides, the Constitution, I respectfully submit, is a legal document. Words have got a fixed meaning. We cannot incorporate new words with vague meanings in this Constitution and take the risk of misinterpretation in courts of law. I would therefore beg the mover and the seconder not to press this word to be incorporated in the Draft Constitution. If my friends are very enthusiastic about the Hindi language, we are not far behind them; we will support them. But, this is not the place, this is not the occasion to insert Hindi words in the Draft Constitution. Therefore, Sir, purely as a matter of convenience and legal adaptability, the Drafting Committee’s word “State” is quite good. To substitute it by the word “Pradesh” would be to open the flood-gates of controversy, and if there are other amendments to the effect that Kannada words, Tamil words and Hindi words should be substituted in the different Articles of the Constitution then, as I said, the whole draft, as placed before the House, would be a hotchpotch of linguism. I would earnestly request the members not to press these amendments, because it is merely a translation, and not to introduce non-English words into an English Draft.

Lakshmi Kanta Maitra: Mr. Vice-President, I have very carefully listened to the speech just delivered by my honourable friend Mr.Hanumanthaiya opposing the amendment of my honourable friend Mr.Kamath. I must tell at once my honourable friend Mr.Hanumanthaiya that he need not have unnecessarily scented a sort of underhand effort to import Hindi linguism by this amendment. In the course of my speech on the general motion for consideration of the Draft Constitution I dilated at considerable length on the question of States. I pointed out then and point out even now that the expression ‘State’ has got a peculiar connotation in the Constitutional literature of the world. (Cheers). ‘State’ always connotes an idea of sovereignty, absolute independence and things like that. In the United States of America there was a States Rights School. It seriously contended that the States had independent status and the bitterness which was generated by the long drawn out controversy culminated in the bloody civil war. That is the evidence of history. Therefore when we want to describe our country as a Union of States, I apprehend that it is quite possible that the provinces which are now being given the dignified status of States, the native States which had hitherto been under the Indian Princes, but have now either acceded to or merged in, the Indian Union may at a later stage seriously contend that they were absolutely sovereign entities and that the Native States acceded to the Indian Union ceding only three subjects, viz. Communications, Defence and External Affairs. In order to avoid all these likely controversies in the future, I suggested to the House that best efforts should be made to evolve a phraseology in place of ‘States’. We must eliminate the chances of this controversy in the future. I am prepared even now – let my friends ransack and find out a substitute. This word has an unsavory smell about it. In the absence of ‘State’ it has been suggested that the word ‘Pradesh’ should be substituted. Let me tell my friend Mr. Hanumanthaiya and those of his way of thinking that the word may be used in Hindi but it is a Sanskrit word. It is not an English word but there will be no difficulty if it is used. Here you describe in article 1 sub-clause (2) that –

“The States shall mean the States for the time being specified in Parts I, II and III of the First Schedule.“

Lakshmi Kanta Maitra: If you look at Part I of the Schedule, you will find the States that are enumerated there are the Governors’ provinces of Madras, Bombay, West Bengal, United Provinces, Bihar, Central Provinces, Assam and Orissa, if you look to Part II you will find Delhi, Ajmer-Merwara, including PanthPiploda and Coorg. I seriously ask, are you going to describe the City of Delhi as a State? Are you going to describe Coorg as a State? Are you going to describe PanthPiploda as a State? Are you going to describe Ajmer-Merwara as a State? If you do it, it will be simply ridiculous. Therefore in the absence of any other suitable expression I do feel that the term ‘Pradesh’ which is of Sanskrit origin and which means a country of big area – would be quite suitable. There will be no harm if, in the first schedule, in the description, the words ‘Pradesh’ I know it is an English translation. There is some force in what my honourable friend said that in the English draft itself you should not introduce Sanskrit words. But my friend coming from Mysore should be the last person to describe his own territory as an Independent State. Does it require any argument? Has he not so far pleaded that these States should have no sovereign existence and that they should be merged with the Union? Therefore there ought to be no sanctity about the word ‘State’. I am perfectly prepared if the Draftsmen or anybody in this House could find an expression which would denote and connote what we want. We have always pleaded for a strong Centre. In the Draft we have a federal structure but the Drafting Committee has rightly imported to it a unitary bias. We appreciate it. If we are to give effect to that view we have got to find out an expression which will thoroughly embody the concept which we have in view. From this point of view, I am convinced that nothing would be lost if we describe the States as Pradesh. In that case, all categories of States, Governors’ provinces, Chief Commissioners’ provinces and what have hitherto been called Native States could all be included under ‘Pradesh’ and ‘Pradesh’ could be enumerated in the First Schedule I support the amendment to substitute ‘Pradesh’ in place of ‘State’.

Rohini Kumar Chaudhuri: I want to oppose this amendment. First of all, I oppose Mr.Kamath’s amendment and it is very easy to ask the House to throw it out. He has asked the word ‘Pradeshas’ to be used in place of the word ‘States’. How does he come to the conclusion that ‘Pradeshas’ if anything. It cannot be ‘Pradeshas’. Therefore on that ground as well as on the ground that if you change the word ‘Pradeshas’ in article 1 and you do not touch the rest of the article, then it becomes meaningless. Therefore on these two grounds I oppose the amendment which has been moved by Mr.Kamath. But I must be careful when I go to oppose the amendment of a person like my friend Mr. Gupta who is the Speaker of the C. P. Assembly.

Rohini Kumar Chaudhuri: Nevertheless, I cannot understand the object of the change he proposes. There may be some sentiment behind it which I may understand, but not appreciate. Here, Sir, you have a Constitution in English and the same Constitution in the language called the National Language – call it Hindi or Hindustani. When you write the Constitution in Hindustani, it is but natural that you should use the word ‘Pradesh’ in place of the word ‘State’ or ‘Province’. But when you are writing the Constitution in the English language, it is not conceivable why you should seek to change the word ‘State’ to ‘Pradesh’. What is the object? That is what I would like to know. If the object is to acquaint people who are not acquainted with Hindi, with the word ‘Pradesh’, that I can understand. People from South India do not understand Hindi, so first of all, let them begin by learning the word Pradesh in the Hindi Language. You start with the word Pradesh now, and next time you give them some other word to learn, and bit by bit bring the language on the people of South India. (Laughter). Is that the object?

Rohini Kumar Chaudhuri: Then again, it will be most unaesthetic as a suffix to the word ‘Pradesh’ for the United Provinces or the Central Provinces. Would you call then United Provinces Pradesh or the Central Provinces Pradesh? And if you were to translate the word Province also into Pradesh, then there would be two Pradesh Pradesh, and all this is rather odd.

Rohini Kumar Chaudhuri: Come to Bengal. What would you call West Bengal? Would you call it West Bengal Pradesh? PaschimBanga Pradesh. I can understand, but I cannot understand putting in the word Pradesh alone.

Rohini Kumar Chaudhuri: All these complications will arise if the word is changed. It will help nobody. On the other hand, it will not go against the sentiments of anyone if the word ‘State’ is used. So I would request Honourable Mr. Gupta to consider this point again.

Rohini Kumar Chaudhuri: If by any mischance, this amendment is carried, you, Sir, will kindly allow us time to make amendments in the First Schedule, because it looks very awkward to say U. P. Pradesh or C. P. Pradesh. I would also like to change from Assam Pradesh to Kamrup Pradesh, because the word Assam jarson everyone’s ears as I find now-a-days.

Seth Govind Das: First of all, Sir, I want to assure the honourable members of the non-Hindi-speaking provinces, that our object in moving this amendment is not to force Hindi on any one. The language controversy need not have arisen so far as this amendment is concerned. We wanted to drop the word ‘State’, and therefore, this amendment is being moved.

Seth Govind Das: I was rather surprised to hear the speech of my Mr.Rohini Kumar Chaudhari. He asked us, if Pradesh is accepted, what is going to happen to U. P. and to C. P.? I want to tell him that it would be Samyukta Pradesh or Madhya Pradesh. It will not be the U. P. Pradesh or C. P. Pradesh. Mr.Rohini Kumar, I think, knows Sanskrit well, and he will agree with me that even if we adopt the word Pradesh in our Constitution, it does not mean that the English word Provinces or Province would be used along with the word Pradesh. If we want to get rid of the word ‘State’ because it has got different meanings in different countries, the only way is to put in the word Pradesh there.

Seth Govind Das: Now, as far as the word Provinces is concerned, another controversy is there. There are newly formed States or Unions of States which may not accept the word Province in the beginning. Though all the provinces would be treated alike in the future, in the beginning, to name these State Unions as Provinces would not be a proper thing. Therefore, in view of these difficulties, we thought that the word ‘Pradesh’ would be the proper word. Even in the English version of the Constitution, I think there should not be any difficulty inputting the word Pradesh. There are many other words which have been taken in the English language, for instance, words like ‘bazaar’ or ‘Rajyas’. For these words, when we form the plural of these words, we add the letter ‘s’, and say’ bazaars’ or Rajyas’ in English. Similarly to make Hindi word into its plural form in the English language you need add only ‘s’. I do not see what difficulty there is to adding ‘s’ to Pradesh also and say Pradeshas when we want the plural form.

Seth Govind Das: I hope, Sir, that controversy of language and other questions will not be raised here, and if we think the word ‘ State’ should be dropped, and under the present circumstances, the word ‘provinces’ cannot be taken up, I think the best thing would be to put in the word ‘Pradesh’ both in the Hindi Constitution and in the English Constitution.

Jawaharlal Nehru: Sir, I do not wish to enter into any lengthy arguments on this question, but only wish to point out what my own reaction to this proposal is. When we met sometime back in the two committees – the Union Constitution Committee and the Provincial Constitution Committee – we met jointly, and we considered this matter, and also as to what the names of the Houses should be. After considerable discussion, we came to the conclusion that one of the Houses should be called the House of States. So I say this matter was discussed then in various forms. Now I feel that at the present moment, if any change is made in the name of a province, and it is called a Pradesh, personally I think it would be a very unwise change. (Hear, hear). For the moment, I am not going into the merits of it. It may be, we may have to change, but if so, there should be some uniformity about these changes all over the place. It is not right to push in one or two words here and there. They do not fit in aesthetically, artistically, linguistically or in any other way.

Jawaharlal Nehru: Apart from all this, the argument that was advanced, that “State” somehow meant something which we did not wish our units to mean, I think, was not a very strong argument. The example of the United States of America was given. A State is just what you define it to be. You define in this Constitution the exact powers of your units. It does not become something less if you call it a “Pradesh” or “Province”. On the other hand “Pradesh” is a word which has no definition. No one knows what it means. With all respect, no one present in this House can define it because it has not been used in this context previously. It has been used in various other contexts. It is a very good word, and gradually it may begin to get a significance, and then of course it can be used either in the Constitution or otherwise, At the present moment, the normal use of the word varies in hundreds of different ways and the word “State” is infinitely more precise, more definite, not only for the outside world which it is, but even for us. Therefore, it will be unfortunate if we used a completely improvised word, which becomes a linguistic anachronism for a Constitution of this type. Now, I can understand the position when our constitution is fully developed and we have it in our own language with all the appropriate words. Whether “Pradesh” is the right word or not, I cannot say. That is for the experts to decide and I will accept their decision. For the moment we are not considering that issue. We are considering what words should be brought into this present English draft of the Constitution and bringing in words which will undoubtedly sound as odd and inappropriate tom any ears in India is not good enough. The use of the word in a particular context is foreign. One has to get used to it, especially in regard to the context, and the more foreign words we introduce, the more you make it look odd and peculiar to the average man. My own test would be not inputting up linguistic committees and scholars, but taking a hundred odd people from the bazaar and discussing the matter with them and just seeing what their reactions are. We talk in terms of the people but in fact we function often enough as a select coterie forgetting what the people think and understand. Obviously in technical matters you cannot go to the people for technical words, but nevertheless, there is an approach that the people understand. Therefore, I would beg this House to consider it from this point of view and maintain the normal English word in the English Constitution and later on consider the matter as a whole as to what other words in our language you will be putting in our own draft, which will obviously have an equal status. But putting it in this would be confusing, and looking at it from a foreign point of view, it would be very confusing because no one would be used to it and it would take a long time even to understand the significance of these changes. For myself I am clear that there should be no difference in the description of what is now a province and what is now a State. There should be a uniformity of description in the two. The proposal is that the word “State” should apply to both, and the second House, if approved, should be called the House of States.

Jawaharlal Nehru: There is another matter. This touches, whether we wish it or not, several other points of controversy in this House. They may be linguistic or call it by any other word. I think it would be unfortunate if we brought in those particular controversies in this way, as if by a side door. Those have to be faced, understood and decided on their merits. There is undoubtedly an impression that changes brought about in these relatively petty ways affect the general position of those issues. I think in dealing with the Constitution, we should avoid that. The Constitution is a big enough document containing principles and deciding our political and economic make-up. As far as possible I should like to avoid those questions which, though important we could decide in the context of the drafting of the Constitution. Otherwise, what is likely to happen is that we shall spend too much time and energy from the constitutional point of view on irrelevant matters, although important, and the balance of our time and energy is spent less on really constitutional matters. Therefore, I beg the House not to accept the two amendments moved and to retain the word “State”.

B. R. Ambedkar: I oppose the amendment.

Vice-President: The question is:

“That in article 1 for the word “State” wherever it occurs, the word “Pradesh” be substituted and consequential changes be made throughout the Draft constitution.”

H. V. Kamath: I ask for a division.

Vice-President: It seems to me that the “Noes” have it. It is not necessary for me to call for a division. I have the power not to grant this request. I would request honourable Members to consider the position. It seems to be quite obvious that the “Noes” have it.

Ghanashyam Singh Gupta: I accept the position that the “Noes” have it.

Jawaharlal Nehru: May I suggest that instead of making our requests, we could raise our hands. That would give a fair indication how the matter stands.

Vice-President: Does the Honourable Shri G. S. Gupta admit that the “Noes” have it?

Ghanshyam S. Gupta: I accept the position that the “Noes” have it.

The amendment was negatived

H V Kamath then moved another amendment to replace the word ‘States’ to ‘provinces’.

H. V. Kamath: Sir, I beg to move:

“That in clause (1) for the word ‘States’ the word’ provinces’ be substituted.”

Biswanath Das: On a point of order, Sir, in view of the fact that the previous amendment has been rejected by the House this amendment would be out of order.

Vice-President: The only thing that has happened is the rejection of the word “pradesh“.

H. V. Kamath: Mr. B. Dasrose to a point of order to the effect that this is not in order. The amendment that has been thrown out by the House is to the effect that the word ‘Pradesh’ be substituted for the word ‘State’, which does not rule out this amendment, viz., the substitution of the word ‘State’ by any other word, if the House so chooses. I have therefore moved my amendment that for the word ‘State’ in the article and wherever it occurs throughout the Draft in this context the word’ Province’ be substituted. The formal amendment is that in this particular clause the word ‘State’ be replaced by the word ‘Province’. When I moved my first amendment with regard to the word ‘Pradesh’ I made my position clear as to why I am against the retention of the word ‘State’. I do not wish to repeat those arguments which I then advanced before the House. I might just recall them by saying that the word ‘State’ smacks of imitation as the word finds a place in the constitution of the U. S. A. Secondly the word ‘State’ has a bad connotation or bad odour about it, because of the association of the Indian States with the British regime which is now dead. I would therefore in all circumstances plead with this House the word ‘State’ should be eliminated at all costs and by all means and if the House is not in a mood to accept the word ‘Pradesh’ I would certainly entreat them to accept the word ‘Province’, as the lesser of the two evils. Our position today is that we have dispensed with or eliminated the old Indian States; and have we not already adopted the terms Himachal Pradesh and Vindhya Pradesh? We want to level them up to the position of the Indian Provinces and therefore in the new set up I feel that the word ‘Province’ is more happy and would express the meaning of the structure of the component units amendment and commend it to the acceptance of the House.

Hriday Nath Kunzru: Sir, if after every motion is moved by a member and you ask Dr.Ambedkar whether he agrees to it and after allowing him to express his views you debar other members from speaking on the subject, it will be very hard on the House.

Vice-President: I am afraid Hriday Nath Kunzru has not realised exactly my position. I am always prepared to give every possible facility to every member here, which I need not demonstrate further than by reference to what I have done in the last few days. But just now we are pressed for time. After Mr.Kamath moved his amendment I waited for some time to see if anybody would stand up and nobody stood up and when specially I found that Mr.Kamath had repeated the arguments which had been formerly stated by him, I thought that I would not be going against the wishes of the House by asking Dr. Ambedkar the question whether he wished to reply. If I failed to understand the attitude of the House I am very sorry.

Hriday Nath Kunzru: You are perfectly within your right in not allowing discussion of a clause which you regard as trivial and on which you think there has been sufficient discussion. You have the power to stop discussion and ask the Member in charge to reply. If in exercise of this power you asked Dr.Ambedkar to reply, there can be no objection to what you have done.

Vice-President: Then I will put the amendment to vote. The question is:

“That in clause (1) of Article 1, for the word ‘States’ the word ‘Provinces’ be substituted.”

The motion was negatived.