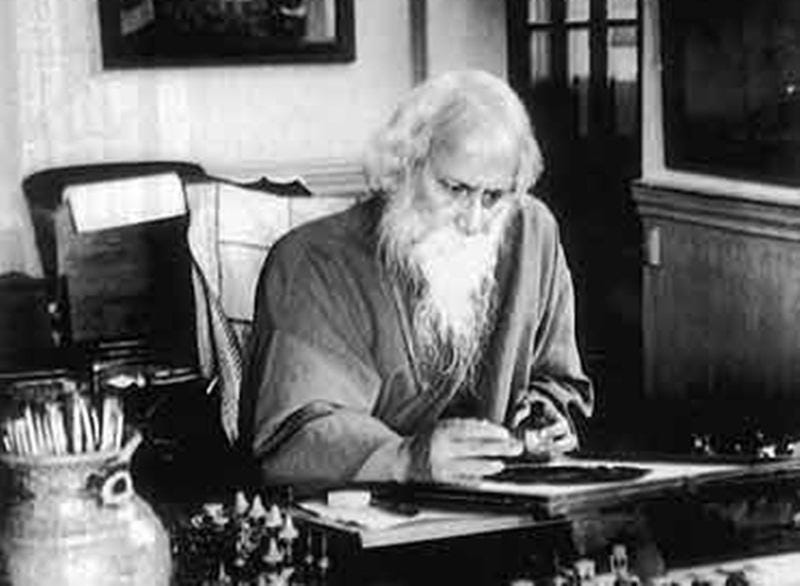

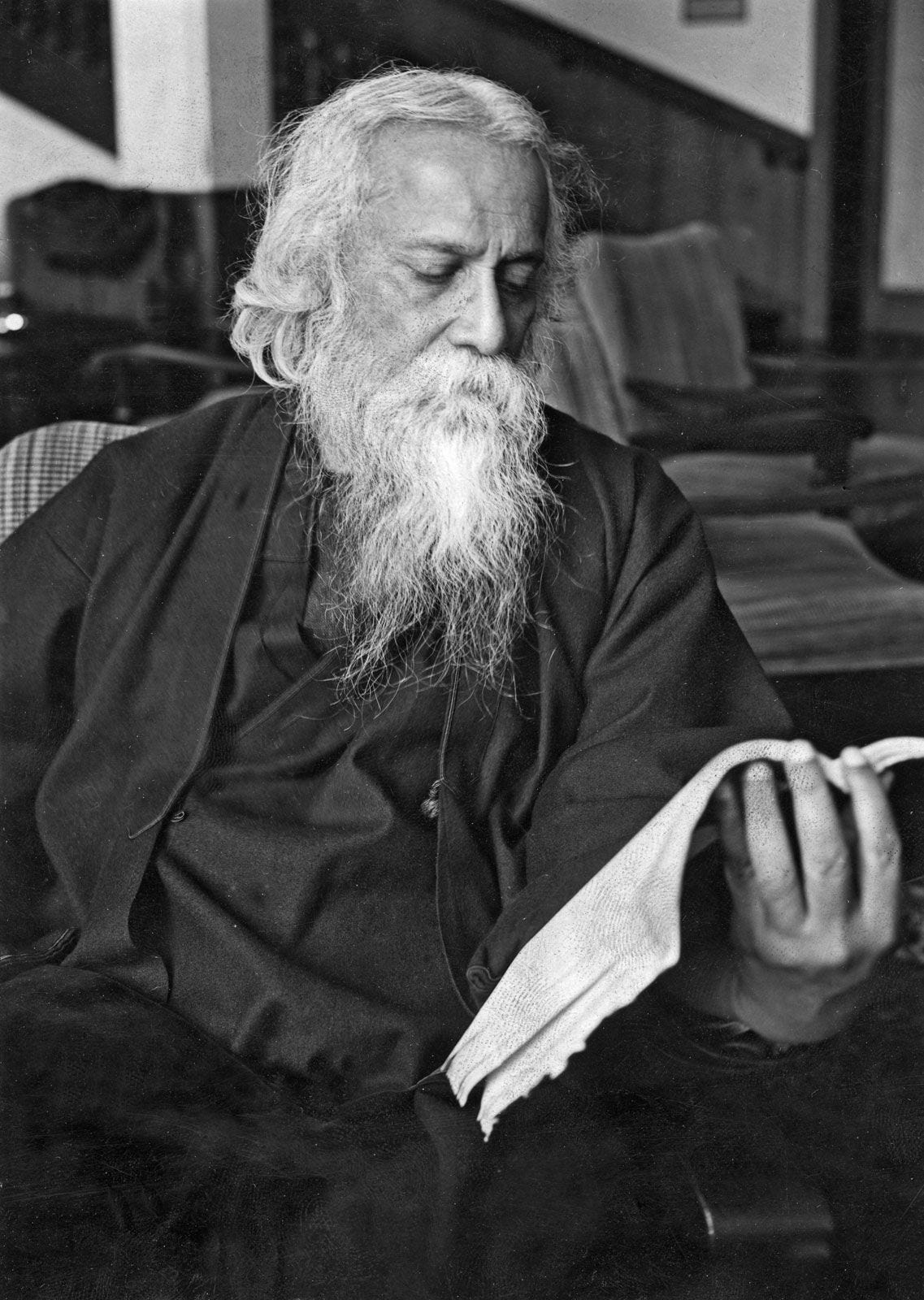

Dispatch #76: Tagore and Nationalism

At a time when there's a repeated attempt by the right-wing to appropriate Tagore, it is important to understand his views on nationalism and patriotism.

It’s been 40 years since Benedict Anderson wrote Imagined Communities-Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. The most succinct definition of ‘nation’ was given by Anderson in his influential book. He defined a nation as an imagined community. Imagined because most of the people living in a nation would never meet or see each other in their lifetimes, yet there is a commonality that binds them together.

It is imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion. The nation is imagined as limited because even the largest of them, encompassing perhaps a billion living human beings, has finite, if elastic, boundaries, beyond which lie other nations. No nation imagines itself coterminous with mankind. The most messianic nationalists do not dream of a day when all the members of the human race will join their nation in the way that it was possible, in certain epochs, for, say, Christians to dream of a wholly Christian planet. It is imagined as sovereign because the concept was born in an age in which Enlightenment and Revolution were destroying the legitimacy of the divinely-ordained, hierarchical dynastic realm. Finally, it is imagined as a community, because, regardless of the actual inequality and exploitation that may prevail in each, the nation is always conceived as a deep, horizontal comradeship. Ultimately it is this fraternity that makes it possible, over the past two centuries, for so many millions of people, not so much to kill, as willingly to die for such limited imaginings.

Anderson’s idea of a nation as a ‘horizontal comradeship’ is quite an antithesis to the idea of nationalism propounded by the right wing which is premised on the exclusion and otherness of minorities. The latter is vacuous, loud, jingoist, exclusionary, and violent.

At this juncture it’s pertinent to understand Tagore’s views on nationalism and why he looked at it with suspicion.

Ashis Nandy in his article titled ‘Nationalism, Genuine and Spurious’ argues that Tagore was skeptical about the conceptualization of nationalism in Europe, during the 19th century. According to Tagore, nationalism is not compatible with the syncretism of India. This skepticism was visible in his 3 iconic political novels- Gora, Ghare Baire, and Char Adhyay.

Tagore’s understanding of nationalism – that is, its genuine European version that took its final shape in the 19th century as an inseparable adjunct of the modern nation state and the idea of nationality – is explicit in a number of essays and letters, but the most moving and disturbing exploration of the social and ethical ramifications of the idea is in his three political novels: Gora, Ghare Baire and Char Adhyay. Each of the novels is built around a significant political formulation, though it is doubtful if the poet did so deliberately. In Gora, Tagore gives a powerful psychological definition of nationalism where nationalism becomes a defence against recognising the permeable or porous boundaries of one’s self that the cultures in his part of the world sanction. He in effect argues that the idea of nationalism is intrinsically non Indian or anti-Indian, an offence against Indian civilisation and its principles of religious and cultural plurality. Ghare Baire is a story of how nationalism dismantles community life and releases the demon of ethnoreligious violence. It destroys the “home” by tinkering with the moral basis of social and cultural reciprocity and hospitality in the Indic civilisation. Char Adhyay is an early, perhaps the first exploration of the roots of industrialised, assembly line violence as a specialisation of the modern times. It anticipates the works of Hannah Arendt, Robert J Lifton and Zygmunt Bauman on the changing nature of organised mass violence and its links with nationalism.

Nandy further argues that Tagore’s belief in the cultural unity of India was not rooted in the ‘canonical texts’-the Vedas, the Upanishads, and the Gita. Unlike the 19th-century thinkers like Rammohun Roy, Vivekananda, and Aurobindo, who made these texts the basis to explain Indian unity, Tagore referred to the mystics, poets, and thinkers of the 13th century to explain the Indianness and Indian unity. Nandy adds, “In such a country, importing the Western concept of nationalism was like Switzerland trying to build a navy.”

Tagore’s position opened up the possibility of viewing India as a cultural entity defined by a number of mystics and saints, the boundaries of whose religious identities were never exactly clear. Like Kabir, Nanak, Bulleh Shah and a Lalan they could simultaneously belong to more than one religious tradition. Also, this way of defining India’s oneness partly dissociated Indianness from the state and allowed some degree of scepticism towards the ideology of a national state, an ideology towards which modern India was already showing a certain fondness.

Further into the article, Nandy goes on to explain what is nationalism, drawing from Tagore’s ideas on the subject. Read these words carefully because no other literature on nationalism will explain the idea better than this.

Nationalism is an ideology. Even those who use the term nationalism without caring about its ideological contents, end up imbibing some of the contents. This is because they have to constantly interact with those who carry the ideological baggage of nationalism and are affected by such consensual validation. Nationalism, thus, is more specific, ideologically tinged, ardent form of “love of one’s own kind” that is essentially ego-defensive and overlies some degree of fearful dislike or positive hostility to “outsiders”. It is ego defensive because it is often a reaction to the inner, unacknowledged fears of atomisation or psychological homelessness induced by the weakening or dissolution of primordial ties and growing individuation, alienating work and the death of vocations, in turn brought about by technocratic capitalism, urbanisation and industrialisation. Often such nationalism is honed by the uprooting – and the consequent sense of loss – that urbanisation and development bring about.

Nandy draws a clear distinction between nationalism and patriotism.

Unlike nationalism, which demands a uniform allegiance or loyalty to the state, patriotism can live with different levels of loyalty, affiliation and allegiance to the state. The relationship between the state and patriotism is open to bargaining. Nationalism insists on the primacy of national identity over identities built on subnational allegiances – religions, castes, sects, linguistic affiliations and ethnicities. It promotes decontextualised formulae or slogans like “we are Indians first, then Hindus, Tamils or dalits”. For nationalism expects all identities to be subservient to the interests of the national state. As a general rule, nationalism fears other identities as potential rivals and subversive presences. Patriotism does not automatically demand such primacy; on the whole, the state is expected to serve the needs of a society and a culture, not the other way round.

Tagore’s critique of nationalism comes from his critique of modern civilization. According to JNU professor Mohinder Singh’s article titled ‘Tagore on Modernity, Nationalism and the Surplus in Man’, Tagore defines a nation as “the political and economic union of a people” and this union is the one that “a whole population assumes when organized for a mechanical purpose.” This is too narrow a definition, according to Tagore, to fit into the realities of a multicultural society like India.

The goals of this form of political organisation are endless enhancement of its economic, military, and political power and continuous ideological self-aggrandisement. Externally, at international level, nationalisms work either through diplomatic deception, lies and instrumentalisation of other nations, or through overt threat, aggression and war. Commerce and science are used by nationalisms instrumentally to attain their ever-expanding power goals, without any clear telos to give them any sense of ethical limits of their actions. Since nation states are ever in competition with each other, the spirit of unhealthy and unending competitiveness determines their behaviour externally, whereas strong disciplining and regulation of people determine their behaviour internally.

In 2016, a Supreme Court bench made it mandatory for cinema halls to play our national anthem and people must stand up as part of their ‘sacred obligation’ to the anthem. I think the bench never read Tagore for whom patriotism was never such a narrow and facile concept. In a letter to his friend A. M. Bose, in 1908, he wrote, ‘Patriotism can’t be our final spiritual shelter. I will not buy glass for the price of diamonds and I will never allow patriotism to triumph over humanity as long as I live’. I am sure a man who, in 1919, rejected his knighthood in protest against the Jallianwala Bagh massacre can not be less patriotic. Tagore was a radical thinker who challenged not only the narrow visions of nationalism and patriotism but also the Brahminical domination over the Hindu religion which added more rigid boundaries in the society and reduced religion to mere customs and rituals. In a letter to Gandhi, in 1933 he said this:

It is needless to say that I do not at all relish the idea of divinity being enclosed in a brick and mortar temple for the special purpose of exploitation by a particular group of people. I strongly believe that it is possible for simple-hearted people to realize the presence of God in the open air, in a surrounding free from all artifcial obstruction. We know a sect in Bengal, illiterate and not dominated by Brahminical tradition who enjoy a perfect freedom of worship profoundly universal in character. It was the prohibition for them to enter temples that has helped them in their purity of realization.

Tagore’s essay ‘Nationalism in the West’ is a testament to why his ideas are still relevant in 21st-century India. He cautioned the world, by giving the example of Japan, about what happens when people submit themselves to a higher power uncritically. He wrote:

I have seen in Japan the voluntary submission of the whole people to the trimming of their minds and clipping of their freedom by their government, which through various educational agencies regulates their thoughts, manufactures their feelings, becomes suspiciously watchful when they show signs of inclining toward the spiritual, leading them through a narrow path not toward what is true but what is necessary for the complete welding of them into one uniform mass according to its own recipe. The people accept this all-pervading mental slavery with cheerfulness and pride because of their nervous desire to turn themselves into a machine of power, called the Nation, and emulate other machines in their collective worldliness.

It was quite hilarious and ironic to see the BJP trying to co-opt Tagore’s legacy in May this year on his birth anniversary and in 2021 sometime closer to the assembly elections. This, on so many levels, is quite absurd given the fact that in his famous essay Hindus and Muslims, Tagore articulated the controversial idea that the concept of Hinduism is a modern phenomenon, something which the likes of Romila Thapar and more recently Divya Dwivedi have been saying. This single idea has the power to shake the very foundations of the right-wing majoritarian politics in India. I will end with a few passages from this essay for you to appreciate how Tagore challenged the so-called custodians of nationalism in India then and how his ideas continue to do so even now.

It is the fate of the India that two religions like Hinduism and Islam have come together. Though Hinduism doesn’t have strong prohibitions, it has formidable customs. In Islam, on the other hand, custom isn’t insuperable but religious belief is strong. While one side has a door open, the other side’s door is shut! How can the two religions come together then? At one time different nationalities like the Greeks, the Persians and the Scythians mingled freely and lived together in India. But you must remember that this happened before the advent of Hinduism. The advent of the Hindus became an era of reaction—it was the period when the belief of Brahmins was consolidated in the country purposively. Hinduism blocked itself by erecting a wall of custom that was not going to allow anyone to scale it. But one thing was not kept in view—any living thing is going to die if anyone tries to control it by wrapping it up. In any case, the outcome was that at a particular moment of our history after the Buddhist period there was a bid to preserve the purity of the Hindu religion after it had brought races like the Rajputs within its fold to erect a huge fence that would prevent any more alien customs or infuences from pervading it. Key to this move was the prohibition and rejection of others. Nowhere else in the world could one see such an obstacle created by means of such an adroit strategy. This obstacle was designed not only to divide Hindus and Muslims. People like you and me who would like to be free through our actions have also been singled out and subject to barriers.So these are the problems but how are we to solve them? The answer is by changing our mindset and by moving on to a new era of relationships. In the manner in which Europe emerged from the middle ages and entered the modern era through the pursuit of truth and by expanding the frontiers of knowledge, Hindus and Muslims will have to venture forth from the walls hemming them in.