Dispatch #86: Tamil Nadu’s model of industrialisation

In this dispatch, we will take a look at how TN’s decentralised industrialisation is redefining the state’s growth story

In an article titled ‘Tamil Nadu’s decentralised industrialisation model’, Harish Damodaran argued that the state’s cluster-driven capitalism and entrepreneurs from ‘ordinary peasant stock and provincial mercantile castes’ are two major factors driving its industrial growth.

TN’s growth story has always been a subject of academic scrutiny. Scholars have tried to explain its economic growth model through the lens of lower caste mobilisation, sub-nationalism, greater focus on human capital spending etc. The subnational variations in economic and social outcomes always lead to comparing TN with the northern Indian states and other policy challenges. TN has managed high levels of economic growth with high and sustained spending on human development. In their book ‘The Dravidian Model ', authors Kalaiyarasan A. and Vijaybaskar M. argue that the ‘democratisation of economic opportunities has made such broad-based growth possible even as interventions in social sectors reinforce the former’.

TN has done well in structural transformation by lowering its dependence on agriculture and increasing economic activities in industry, construction and services.

Table 1 shows the remarkable structural transformation that TN has undergone over several decades. Agriculture’s share in Gross Value Added (GVA) and workforce is lesser than the all-India average. TN’s share of industry, construction and services in GVA and employment has been higher than the national average. Moving people out of agriculture and putting them in industry, construction and services makes TN India’s foremost state in terms of economic complexity, measured by the diversity of its GVA and employment profile, argues Damodaran. The economic complexity doesn’t stop at the sector level. Within each sector, the diversities have led to the growth of individual industries in TN.

Damodaran adds:

Another indicator of economic complexity is agriculture itself. About 45.3% of TN’s farm GVA comes from the livestock subsector, the highest for any state, and well above the 30.2% all-India average.

This sectoral diversity has resulted in the emergence of several industries such as Hatsun Agro Products which is India’s leading private-sector dairy company, Suguna Foods which is one of India’s leading poultry companies, SKM group which is known for its egg processing units making Namkkal district as India’s egg capital.

TN’s cluster-based industrialisation is one of the key factors behind the rise of more such industrial towns. Damodaran explains:

The economic transformation of TN has been brought about by medium-scale businesses with turnover between Rs. 100 crore and Rs. 5000 crore (some like Hatsun and Suguna have graduated to the Rs 5000 - Rs 10,000 crore bracket). Its industrialisation has also been more spread and decentralised via the development of clusters.

These clusters are agglomerations of firms that specialise in particular industries. The late 19th-century economist Alfred Marshal was the one who pioneered the idea of ‘industrial districts’, which were agglomerations of small and medium firms situated nearby, deriving benefits from other firms’ comparative advantages. The article mentions some of TN’s prominent clusters such as:

Tirupur for cotton knitwear (exports of Rs. 34,350 cr & domestic sales of Rs. 27,000 cr in 2022-23)

Coimbatore for spinning mills and engineering goods (from castings, textile machinery and auto components to pump sets and wet grinders).

Sivakasi (safety matches, firecrackers and printing).

Salem, Erode, Karus and Somanur for powerloom and home textiles.

The Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) under the Cluster Development Program (CDP) has developed cluster development as a key strategy for enhancing productivity and competitiveness and building the capacity of MSMEs. The definition of a cluster, according to the ministry is:

A group of enterprises located within an identifiable and as far as practicable, contiguous area or a value chain that goes beyond a geographical area and produces same/similar products/complementary products/services, which can be linked together by common physical infrastructure facilities that help address their common challenges.

The broad objectives of the cluster development program are:

To support MSMEs by addressing common issues such as technology, skills and market access.

To build the capacity of MSMEs for common supportive action through the formation of SHGs, consortia etc.

To create/upgrade infrastructure facilities in the new/existing industrial areas.

To set up common facility centres (CFCs) for testing, training, raw material depot, effluent treatment, complementing production processes etc.

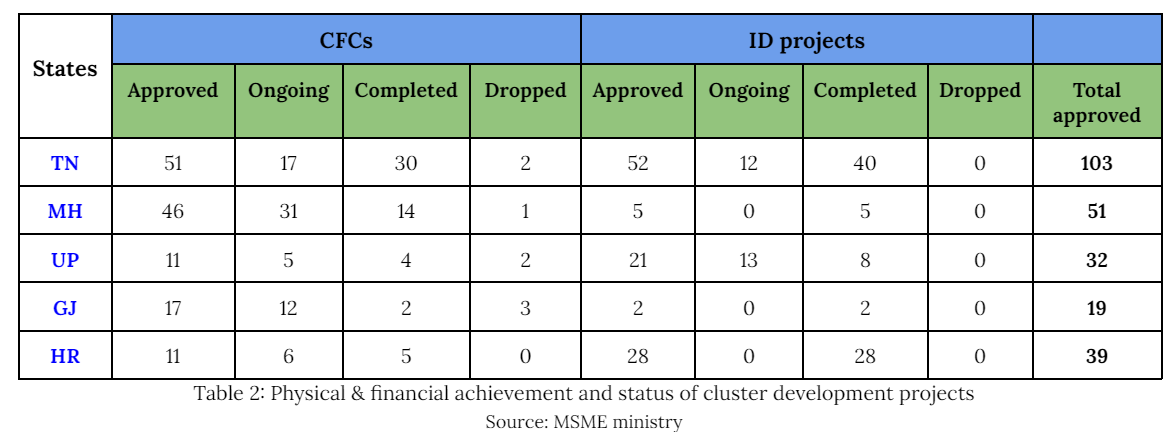

According to the latest data (as shown in Table 2 ) from the MSME ministry, TN has the maximum number of common facility centres (CFCs) and infrastructure development (ID) projects when compared with the other 5 states that have high GVA shares in manufacturing.

Damodaran adds:

Most of these clusters have come up in small urban or peri-urban centres, providing employment to people from surrounding villages who might otherwise have migrated to big cities. They have also created diversification options outside of agriculture, reducing the proportion of the workforce dependent on farming.

The second most distinctive element of TN’s model of industrialisation is its decentralised nature - the rise of entrepreneurs not from the dominant castes, but from ‘more ordinary peasant stock and provincial mercantile castes’. Damodaran explains how TN’s early big industrialists belonged to Nattukottai Chettiar (Tamil mercantile community) and Brahmin castes. This transformation in the ownership of businesses resulted from the social movements that TN has witnessed for decades. One of the biggest success stories of this transformative phenomenon is the spectacular rise of the Nadar community. Ashutosh Varshney explains:

The breakdown of caste hierarchy has broken the traditional links between caste and profession and released enormous entrepreneurial energies in the south. This breakdown goes a long way to explaining why the South has taken such a lead over the North in the last three decades. Unlike northern India, where caste-based political movements are a fairly recent phenomenon, lower castes in southern India began agitating against upper-caste domination at the beginning of the 20th century. Because these movements arose before independence and the possibility of elected political power, they focused on issues like dignity, education, and self-reliance.

In the article, Damodaran gives several examples of such entrepreneurs, from non-traditional mercantile castes, and the businesses that they have established in TN:

Coimbatore’s spinning mills, foundries, machines, pumps, textile equipment and compressor-making units - Kammavar Naidus

Suguna foods (poultry) - Kammavar Naidus

CRI pumps (fluid management solution providers) - Kammavar Naidus

ELGi equipment (air compressors) - Kammavar Naidus

Lakshmi Machine Works (industrial machinery) - Kammavar Naidus

SKM Group (poultry) - Kongu Vellala Gounder

Ramraj cotton - Kongu Vellala Gounder

Sivakasi fireworks, matches and printing industries - Nadars

Damodaran concludes:

This entrepreneurship from below combined with high social progress indices from public health and education investments probably explains TN’s relative success in achieving industrialisation and diversification beyond agriculture.

TN’s model of economic growth which relies on decentralised industrialisation and entrepreneurship from below has been the single biggest factor why unrest among agrarian communities has been absent in the state, argues Damodaran in another article titled ‘How TN’s rural industry model can keep farm unrest at bay’. While in other states moving millions of people out of agriculture was difficult because of a lack of alternatives, TN’s decentralised industrialisation provided options to the agrarian communities to move to other sectors.

Damodaran argues:

Keeping options open is something that agricultural communities like the Kongu Vellala of the western TN have been able to exercise much better than their counterparts elsewhere - for whom farming is more a compulsion than choice. This has been made possible mainly by decentralised industrialisation. GJ, MH & TN are 3 states where manufacturing’s share in the GDP is higher than every other sector, including agriculture. The difference, however, is that manufacturing activity is much more spread out and decentralised in TN.