Dispatch #88: Structural Transformation in Tamil Nadu

In this dispatch, we will look at the data which shows how structural transformation happened in TN over the past few decades.

Kalaiyarasan A from Madras Institute of Development Studies wrote a paper in 2020 titled ‘Structural Change in Tamil Nadu, 1980-2010: Limits of Subnational Development’ in which he chronicles the economic development of the state using key macroeconomic indicators. He begins the essay by admitting that the fundamental problem that the Indian economy faces is its inability to transform itself structurally. Structural transformation essentially means ensuring that resources flow rapidly to modern economic activities operating at higher economic productivity levels (for instance industries, manufacturing and services).

Let’s spend some time understanding structural transformation and economic growth in a more nuanced manner.

Dani Rodrik, argues that a country needs to overcome two challenges before hitting a high economic development path:

Structural transformation challenge: Moving resources from low-productivity areas to high-productivity areas.

Fundamentals challenge: Accumulating skills and institutional capabilities needed to generate productivity growth. These fundamentals may include human capital development (education, skills and training) and quality of institutions (governance, rule of law and business environment).

The conventional understanding is that an increase in human development spending and a focus on improving the institutional set-up will lead to high economic growth. Rodrik, however, contests this argument and adds that it’s not that straightforward. It is possible to have radical structural transformation without a significant focus on fundamentals (human capital development and institutions). Rodrik gives examples of China, East Asian countries and Vietnam. At the same time, a country’s fundamentals may be strong but in terms of structural change, there isn’t any significant movement, for example, in Latin America in the 1990s, where governance and macroeconomic fundamentals were reasonably strong, sectors such as manufacturing lost its ability to provide mass employment.

Rodrik proposes the following framework to understand how the two factors - structural transformation challenge and fundamentals challenge - can affect a country’s overall economic development.

The structural transformation in TN is unique as it combines high economic growth and human development. As seen in the previous two dispatches, the transformation of the state has been broad-based in terms of economic sectors that have seen high growth and the economic growth is also spatially widespread.

Let’s look at some of the historical data to understand the transformation. I have used UP for comparison as the state has always been regarded as the basket case and has been at the centre of recent debates where its economic model was compared with that of TN.

Figure 2 compares the per capita net state domestic product (at constant prices) of the two states. The per capita net state domestic product (NSDP) is the measure of the economic output of the state divided by its population.

The per capita NSDP of UP and TN was almost at the same levels till the early 90s. The divergence began in the late 90s and continued thereafter. The per capita NSDP of UP in 2022-23 was ₹ 47066 which was the per capita NSDP of TN in 2009-10 (₹ 47394).

The gross state domestic product (GSDP) is the measure, in monetary terms, the sum total of finished goods and services produced during a given time within the boundaries of the state. There has been a difference in the GSDP of both states, during most of the past decade, with TN having a marginally higher GSDP than UP. The Minister of Information Technology and Digital Services of TN, PTR Madurai cautions us:

The data system in India is such that it is hard to state any year’s GSDP with any accuracy until more than 12 to 18 months after the close of the year, compared to about six months for countries like the US.

He further adds:

GSDP and GDP are notoriously hard to estimate given the data systems and models in our country. Each of these numbers released by the Central Statistics Office has at least five different estimates over time; it starts with initial estimates (Advance and Provisional Estimates), which are subsequently revised and released as the First, Second, and Third Revised Estimates. The period for the estimates ranges from six months before to 18 months afterwards; these figures remain volatile, and there are always huge jumps between any of these five estimates. This increase in volatility, the substantial lag in publication, and the loss in reliability may perhaps be attributed to this government’s propensity to suppress or avoid data collection as far as possible. This enables the propaganda machinery to proceed full throttle without the fear of facts or truth getting in the way, thereby allowing its preferred narratives to snuff out any substantive debate.

When we look at the growth in GSDP and sectoral growth in both states, we’ll find that overall the growth rates of UP in agriculture, manufacturing and services have been less than that of TN.

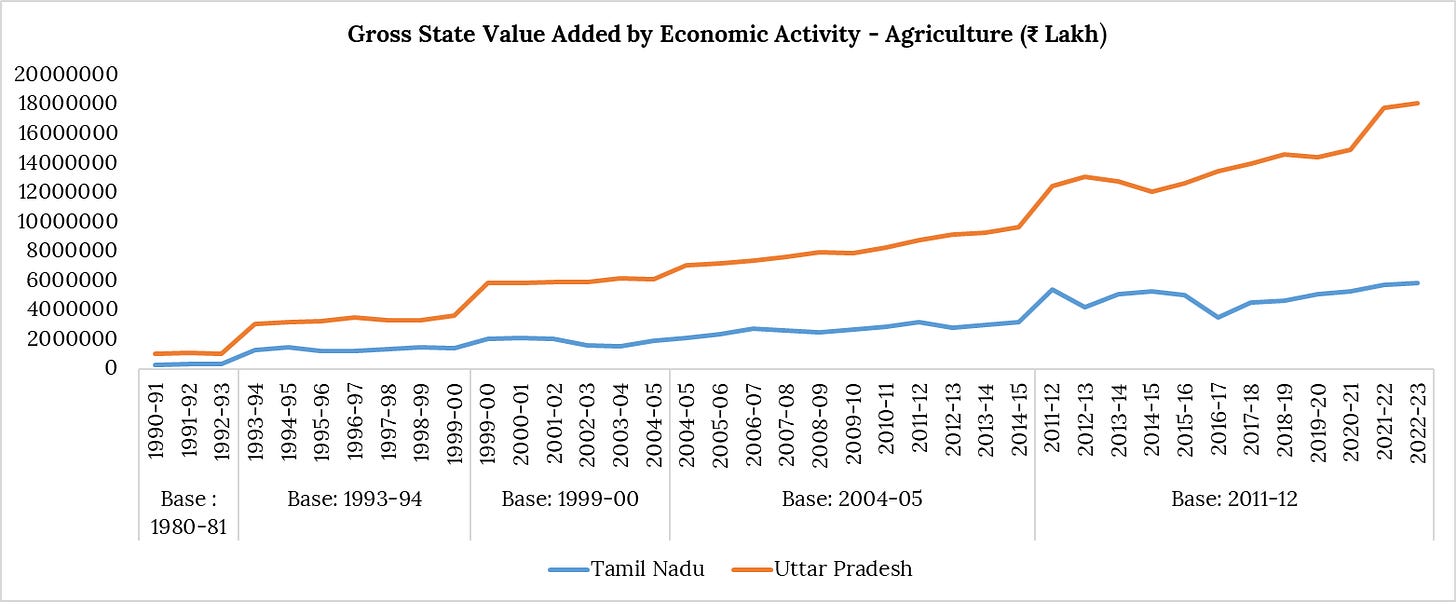

The fact that UP is still heavily dependent on agriculture can be seen from high levels of contribution to the gross state value added (GVA) as shown in the figure below. TN’s GVA by agriculture in FY 2022-23 is of the same level as UP’s GVA by agriculture in the early 2000s.

TN has been consistently performing better in terms of manufacturing over several decades. The graph below shows high levels of diversion in the GVA of manufacturing over three decades when compared with UP. This article aptly explains the industrial growth of TN:

At present, seven of every 10 electric two-wheelers made in India are manufactured in Tamil Nadu and about 40 per cent of all EVs manufactured in India are manufactured in the southern state. Leading original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) - Ola Electric, TVS Motor, Ather Energy, and Ampere Vehicles – have their EV manufacturing facilities in the state and the sector is expected to create 150,000 jobs by 2025.

TN Industries Secretary Arun Roy said this for TN’s industries:

When I look at the industrial ecosystem of the nation, there are few things that stand out. One is its diversity, we are not a state dependent on one or two industries. There is huge diversity in manufacturing, as well as the services sector. Within manufacturing itself, we have automobiles, leather, textiles, general engineering, renewable energy components, and so on. It is not just large industries, we have a very dynamic and deep-rooted micro small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) ecosystem. We have the second-highest number of registered MSMEs in the country. MSMEs themselves are so diverse that there are MSMEs that are at the lower end of the system and are so technologically advanced.

The difference between UP and TN, in terms of GVA in the service sector, is not that much as shown in the figure below. One of the reasons, as pointed out by economists, could be that since industry and agriculture contribute significantly, the share of the services sector would be small. TN has always had a wide manufacturing base as a result of which manufacturing contributes significantly to its growth story. TN CM M.K. Stalin said, a few years ago, that the state would focus on developing the manufacturing and service sector to drive the state’s economic growth.

The CM said:

Some consider focusing on the services sector will give big growth than focusing on the manufacturing sector. However, as far as the state is concerned, it should be at the forefront both in the manufacturing and services sectors, and only then the inclusive Dravida Model of Growth could be achieved.

TN is one of the leading states in the banking and insurance sector. These institutions play an important role in the economic growth of the state.

The Fintech City project in Chennai is going to be the leading global destination for fintech firms by 2025. The strong roots of the banking and finance sector have made conditions conducive for such a large-scale fintech project. This article explains the transformation:

Being a pioneer in the financial sector, the state, through the Fintech City, is vying to attract strategic investment of Rs 12,000 crore and create 1,50,000 jobs once the project becomes fully operational. During the foundation stone laying ceremony of the FinTech City, Industries Minister TRB Rajaa said the project’s first phase will attract over Rs 1,000 crore worth of investments and generate 7,000 employment opportunities for the state, making it an unparalleled hub in financial technology sector. The financial services sector contributes nearly 5% to Tamil Nadu’s Gross State Domestic Product and has grown at a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 10.15% in the last decade. The state boasts the highest credit-deposit ratio in the country and attracts significant foreign direct investment in banking, financial Services, and Insurance (BFSI) services every year. Fintech firms depend on four key pillars: domain knowledge in finance, information technology, infrastructure, and diversified and inclusive markets, all of which are well-established in Tamil Nadu. Interestingly, the first cooperative bank in India, The Madras Urban Cooperative Bank, was set up in Chennai in 1906. The country’s first private mutual fund was also established in Chennai in 1993 after the Government of India allowed private players to manage and operate mutual funds. Tamil Nadu has witnessed the growth of several banks and NBFCs, both in the public and private sectors, including microfinance vehicles such as chit funds. Chennai is home to about 400 financial industry businesses, with nearly 200 located in the main residential clusters of Mylapore, RA Puram, Nungambakkam, and T Nagar. These areas are congested and have put pressure on civic authorities for additional infrastructure. The growth in fintech is driven by a mix of startups and large firms. Startups provide specific and targeted financial products to tap into consumer segments not served by traditional financial institutions. Similarly, large financial institutions enhance their fintech offerings through firms providing digital infrastructure and in-house technology solutions to compete with new entrants or products and retain market share.

One of the most revealing stats that explains TN’s structural transformation and divergence from the states in the North, is the number of factories according to the Annual Survey of Industries.

In 2019-20, UP had as many factory units as TN in the early 90s. Naturally, the number of workers involved in industry or manufacturing will also show the same trend as that of factory units.

Despite having high growth rates in manufacturing, industry and services, Kalaiyarasan concluded, in his paper, that the state faces two main challenges:

Despite such a significant economic transformation, the state has broadly two sets of challenges—the inadequacy of jobs to absorb the labour released from agriculture, and the casual nature of jobs and emerging joblessness for educated youth. First, a steady decline in both the share and absolute number of cultivators since the 1990s suggests a movement of the rural workforce to non-agricultural and urban spaces. The percentage of cultivators in rural Tamil Nadu came down from 29% in 1981 to just 13% in 2011, which is one of the lowest figures across states in India. As a result, the rural is no longer synonymous with agrarian life in Tamil Nadu, with youth withdrawal from agriculture occurring at a faster pace here than in other Indian states. Second is the inability to absorb educated youth in the labour market. Tamil Nadu has become a supply hub for engineers in recent years. The state has 534 engineering colleges, fewer than only Maharashtra. Affirmative action policies in the state’s education sector have ensured access to education across social strata. The gross enrolment ratio in higher education in Tamil Nadu is one of the highest among states and is double the all-India average. However, increased access to education may constitute a problem when, despite investing in education, one finds no returns—as, for example, in a situation where there are not enough jobs to absorb all the engineers that the state has produced. Given the limited generation of quality jobs, mere access to higher education— without proportional diversification in the employment market—does not translate into better prospects for its beneficiaries.