Dispatch #90: Rocking the priors - Do we truly understand the relationship between institutions and economic growth?

In this dispatch, we will explore some of the key arguments that Yuen Yuen Ang presents in her paper on Adaptive Political Economy.

In Adaptive Political Economy: Toward a New Paradigm, political scientist Yuen Yuen Ang argues that social systems are complex and shouldn't be treated like machines. She critiques how social scientists and development scholars often use reductionist methods, mistakenly viewing complex systems as complicated ones that need to be simplified and controlled.

Ang points out the fundamental error social scientists make when studying these systems:

It is a basic classification error, akin to treating liquids as solids, or more colourfully put, mistaking trees (complex, adaptive system) for toasters (complicated, mechanical system). Yet adherents of the mechanical worldview are often proud: they think that by treating trees as toasters, they simplify and control a messy world.

Ang compares the study of complex social systems to fractals—the mathematics of complex shapes. Just as the veins on a leaf require a non-traditional geometric approach, Ang argues that an equivalent of fractals should be the default method for social scientists to understand the world.

She adds:

Instead of pretending that the uneven contours of social systems are straight lines, or ignoring them altogether, political economists should be developing the concepts, methods, and theories to illuminate the order of complexity.

To highlight the flaws of applying traditional geometric concepts to complex shapes, Ang invokes the classic debate among development scholars: what drives economic development—growth or good institutions?

Three schools of thought offer different answers to this question:

Modernization Theory: This theory argues that economic growth precedes political and institutional development. Advocates like Jeffrey Sachs, who pushed for large-scale financial aid to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), support this view. However, it struggles to explain how economic growth begins. In The Idealist, Nina Munk describes how this approach led to failure in Africa’s Millennium Villages Project. One intervention boosted corn yields with fertilizers and high-yield seeds, but without access to markets or infrastructure like quality roads, much of the crop rotted or was eaten by rats.

Institutional Economics: This theory takes the opposite stance, arguing that good institutions are prerequisites for economic growth. Douglas North was a key proponent of this view. However, this approach fails to explain how poor countries without strong institutions can achieve sustained growth. Pritchett and Woolcock have pointed out the limitations of simply replicating best-practice reforms to improve service delivery in developing nations.

Historical Institutionalism: This school argues that colonies with inclusive institutions thrived, while those with extractive institutions stagnated. Acemoglu and Robinson, in Why Nations Fail, explain how Spanish conquistadors established extractive systems in South America, whereas British colonists paved the way for capitalist success through inclusive institutions like equal opportunity and limited government.

Ang highlights a common thread among all three camps and points out flaws in their core arguments:

Like classical mathematics, they all make straight-line arguments. Causality points in one direction, from either growth to good institutions, or vice-versa, or from history to good institutions to growth. All three schools failed to find a way out of the chicken-and-egg problem. Why? Because they took an inherently endogenous (bicausal) process- economic and institutional development- and forced it to fit within their linear, static models.

If current frameworks fall short in analyzing complex social systems, what’s the alternative?

Ang introduces the concept of Adaptive Political Economy (APE) as a solution.

Classical political economy treats social systems—governments, economies, societies, cultures, and institutions—as complicated. In contrast, APE views these systems as complex.

The key distinction lies in how the systems function. Complicated systems consist of separate parts that work together to perform a task, but these parts do not adapt to one another or the external environment. For example, a toaster is a complicated system where different parts are assembled to perform a specific function. The process is linear and predictable—simply follow the manual, and the toaster works as intended.

In contrast, complex systems are composed of interconnected parts that interact and adapt to both each other and the external environment. Trees, for instance, are complex systems, where the veins of the leaves can only be understood through fractal geometry.

Adaptation in complex systems occurs through three mechanisms:

1. Variation: Generating alternatives.

2. Selection: Choosing or assembling alternatives to form new combinations.

3. Retention: Preserving an alternative or finding new ones.

Ang highlights these differences using a clear comparison between complicated and complex systems in the table below.

Some key differences between complicated and complex systems are:

- Causality: In complicated systems (like machines), causality is linear. In complex systems, causality is interdependent—the cause can also be an outcome of another cause.

- Indeterminacy: Complicated systems, like toasters, may break down. Complex systems constantly adapt, creating uncertainty. While risks in complicated systems can be controlled, uncertainty in complex systems is much harder to manage.

- Human Agency: Controlling uncertainty in complex systems is futile. Instead, the focus should be on influencing adaptation and learning, which requires critical thinking.

- Institutional Design: A deeper understanding of complex systems highlights the limitations of control and shifts attention towards institutions. While many scholars view good institutions as the key to progress, they struggle to explain how some countries without inclusive institutions still succeed. They often overlook the adaptability of institutions in such contexts.

Social systems, like the leaves of trees, are complex. Actors within the system are constantly interacting and adapting, creating multiple, interdependent causal relationships.

Ang explains this further:

The big, enduring themes that matter in social sciences - modernization, state-building, innovation, conflict, financial crashes, to name a few- are necessarily complex in nature. They feature multiple variables that interact with one another, and the relevant causes may even evolve over time. Causality goes in two directions and effects can be lagged.

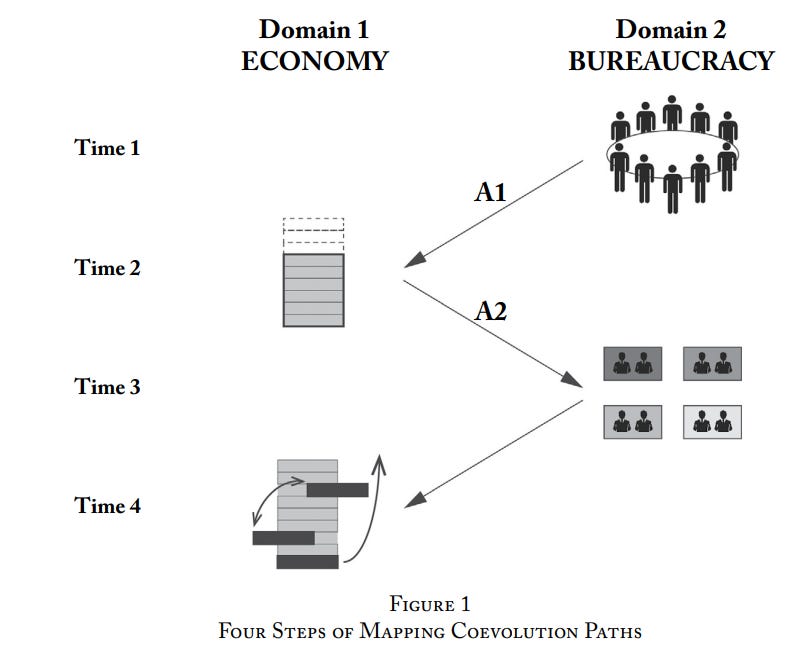

Adaptability is the key concept to understand Ang’s argument that development is a coevolutionary process. This essentially means that development happens when the two key components that drive development - bureaucracy (state) and economy, coevolve with time and each entity adapts to the changes happening to the other entity.

The figure above illustrates how the economy adapts to changes within the bureaucracy, while shifts in the economy drive transitions within the bureaucracy.

Focusing on China’s economic rise, Ang applies this model to explain how market changes in the late 1970s triggered reforms in property laws.

Ang concludes by stating:

First, the institutions, methods, or capacities for building new markets look and function differently from strong (modern) ones that later evolve to sustain mature markets. Indeed, market-building institutions often look wrong to first-world elites. That is why I stress in step one that such institutions are only normatively weak—that is, weak from the first-world perspective. What do conventional models miss? They incorrectly assume that growth-promoting institutions come in one universal package like those found in idealized Western liberal economies. They fail to distinguish between the different needs, constraints, and resources at early and advanced stages of development and the different solutions that could fit. Without acknowledging so, they judge what is best from the standards of the modern and typically Western. Second, the first step of development is using what you have, not what you want. The poor cannot innovate with what they lack: wealth and modern capacity. Necessarily, they must creatively repurpose what they have—practices and resources that the rich may dismiss as backward—to kickstart change. A key word here is repurpose, meaning existing materials do not perform miracles by themselves.