Dispatch #91: The political economy of state capacity

Stuti Khemani’s paper on state capacity emphasises the need to address both political and bureaucratic challenges to build effective government institutions.

Stuti Khemani’s paper on state capacity provides a comprehensive framework for understanding government effectiveness, particularly in delivering public services and maintaining the rule of law. Here's an extended overview of its core themes and arguments, highlighting the nuances and challenges in building state capacity and reforming bureaucratic institutions.

Understanding state capacity: Scope and need

At its core, state capacity is defined as the ability of a government to implement policies and deliver services effectively. This involves more than just enacting laws; it requires strong institutions that can maintain peace, collect taxes, and enforce contracts. Khemani emphasizes that prosperous societies are often those where governments ensure an environment that supports economic growth by providing public goods, such as education, infrastructure, and security, which are essential for a flourishing market economy.

The principal-agent problem in bureaucracy

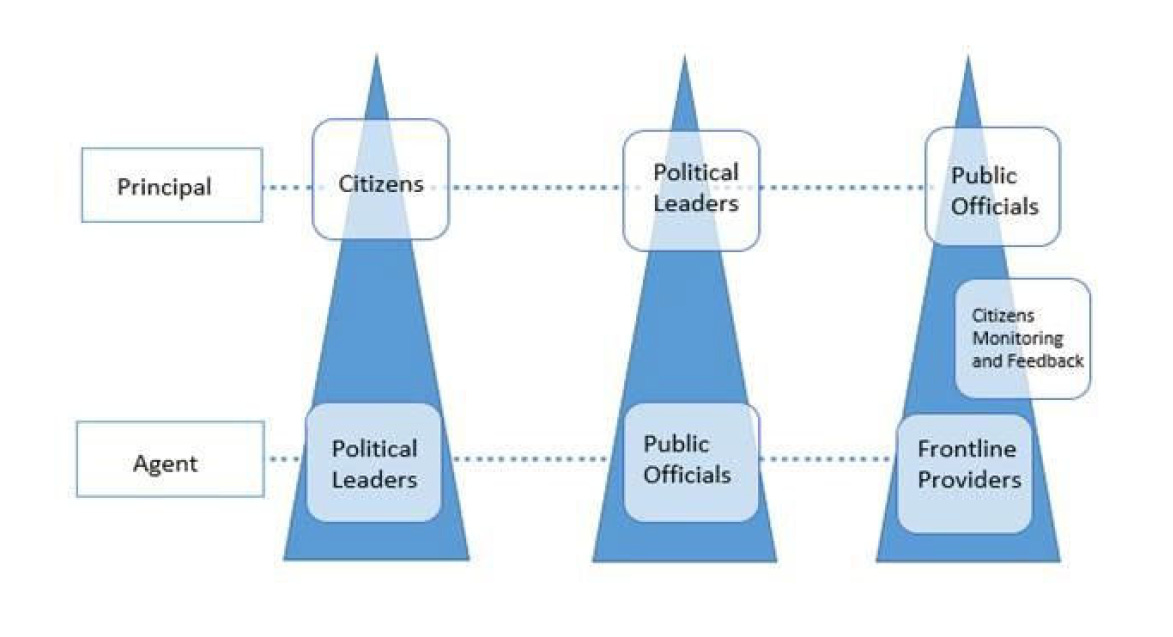

Khemani applies the principal-agent model to explain the challenges within government structures. In this framework, government personnel (agents) work under higher authorities (principals), from top-tier leaders to local officials. Public policies are implemented by the state within the following principal-agent relationships:

Between citizens and political leaders.

Between political leaders and public officials who lead government agencies.

Between public officials and frontline providers.

The problem lies in aligning the interests of these agents with public objectives, which is complicated by bureaucratic structures. When agents prioritize their interests or fall into low-performance patterns, the system's efficiency suffers.

Government agencies often struggle with issues like:

Low accountability: Without clear accountability, public employees may underperform, as the risks of reprimand are low.

Bureaucratic red tape: Excessive regulations and formalities can slow processes and discourage innovation within public agencies.

Rent-seeking behaviour: When government officials exploit their roles for personal gain, it leads to inefficiency and corruption.

Culture and norms within bureaucracies

The paper argues that beyond structural constraints, the cultural norms and shared beliefs among bureaucrats shape the actual capacity of a state. When norms within government agencies support low effort and reward rent-seeking, public service delivery deteriorates. Conversely, effective bureaucracies foster professional norms and a culture that values public service. For instance, countries like Finland and South Korea have robust public education systems because teachers operate within a culture that values meritocracy and professional autonomy.

Politics and its influence on state capacity

Politics plays a central role in shaping state capacity, as political priorities and incentives determine how government agencies function. In countries where political leaders focus on private benefits or clientelism (providing jobs or services in exchange for loyalty), bureaucracy is often weakened. However, in contexts where political competition centres on public welfare, bureaucracies are more likely to prioritize effective service delivery.

Khemani presents a compelling view that high-quality governance arises when political leaders promote a culture that rewards merit and professional ethics. Political contestation, if aimed at broader public goods rather than patronage, can lead to stronger institutions.

Case studies of state capacity development

The paper provides international examples to illustrate how state capacity has evolved under different political and cultural conditions:

China: China’s state capacity stems from a long history of centralized, meritocratic bureaucracy, enabling the state to enforce policy effectively even at local levels. However, this capacity has sometimes led to unintended consequences, as during the Great Leap Forward, when bureaucratic efficiency met disastrous national policies. China’s success in recent economic reforms, however, highlights how state capacity can be redirected toward growth. Khemani explains:

China has a long history of strong state capacity—the ability to get bureaucrats in far-flung areas to follow orders, as well as exercise ingenuity and discretion to accomplishing national goals (Fukuyama, 2011 and 2014). This capacity led to devastatingly tragic outcomes under the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution because of the misguided national goals that bureaucrats were asked to pursue

(Meng, Qian and Yared, 2015). But then the same capacity was turned around for an equally startling escape from poverty when national goals became those of market-style investments for economic growth (Ang, 2016). What Ang does not explain in her book is the origin of this Chinese bureaucratic culture, and the extent to which it may be unique,

or shared primarily with other countries in East Asia. Fukuyama (2014) argues that the origins of Chinese state capacity lie in ancient history, going as far back as the third century B.C., when Chinese emperors began investing in meritocratic recruitment of professional bureaucrats to administer state agencies. Dell, Lane, and Querubin (2018) provide evidence, drawing upon data from Vietnam, that a history of strong states in East Asia has persistent effects to present time, long after the disappearance of those historical institutions, through norms that support local cooperation in the provision of public goods.

United States: In the late 19th century, the U.S. faced high levels of corruption, clientelism, and low state capacity, much like some developing countries today. Political and social shifts during the Progressive Era led to the professionalization of bureaucracies and reforms that fostered autonomy and accountability in government agencies, particularly at the municipal level. Khemani adds:

Politics and bureaucracy in the United States in the 19th century looked very similar to conditions in many developing countries today. Bensel (2004) writes that for many men (women did not have the right to vote) at that time in the United States, “the act of voting was a social transaction in which they handed in a party ticket in return for a shot of whiskey, a pair of boots, or a small amount of money” (Bensel 2004). Politics was

dominated by clientelism and vote-buying; corruption was rife; state bureaucracies and city halls were captured by political leaders and their party machines (Fukuyama, 2018). Things began to change towards the turn into the 20th century, with a large literature examining the so-called Progressive Era in the United States during which bureaucracies were de-politicized. Rauch (1994) describes the reforms in this era that resulted in the professionalization of the bureaucracy in American cities, and the ensuing reduction in the political power to intervene in city management. Glaeser and Goldin (2006), Fukuyama (2018) and World Bank (2016) argue that the confluence of several conditions facilitated this era of bureaucratic reforms: rise in demand among elites for urban public

goods, greater political engagement by non-elite citizens and their dissatisfaction with machine politics; and, greater transparency about corruption in politics through the emergence of a cheap and independent press. That is, favorable political conditions were fundamental to the establishment of professional, autonomous bureaucracies in the history of the United States.

Brazil: The state of Ceara in Brazil provides a model of building capacity in health services by creating a cadre of accountable public health workers and leveraging political support for health goals. This transformation was achieved by instilling norms of professionalism and using media to make health politically salient, shifting local political competition toward service delivery. Khemani gives evidence of how Ceara was transformative by adding:

Tendler and Freedheim (1994) provide a detailed qualitative analysis of the various initiatives that began in Ceara that transformed the health system by creating a professional cadre of health service providers who were held accountable for delivery (eschewing the old system of patronage jobs and political hindrance in service delivery). The reformers

followed a set of complementary “demand” and “supply-side” strategies. Even as they recruited a new cadre of public health workers, and trained them to deliver, they simultaneously took steps to ensure that these workers would not be captured by political patronage. They flooded radio broadcasts (the main news media at that time) with information about the value of public health, and the role of the newly recruited cadre of

public health workers in delivering it. The public health workers told mothers that they should not vote for local politicians who would prevent the health workers from delivering vaccines to their children. In short, health was made politically salient, and health workers were instilled with a sense of professionalism and driven by peer pressure to perform.

Reform strategies for building state capacity

The paper offers strategies for reformers aiming to strengthen state capacity:

Autonomy and accountability: Granting bureaucrats more autonomy, combined with performance-based accountability, can help overcome the limitations of traditional top-down management.

Leveraging technology: Technological interventions, such as secure payment systems for welfare programs, can reduce reliance on intermediaries, minimizing corruption and improving efficiency.

Building professional norms: Successful reforms are those that foster a sense of professionalism and mission within government agencies. This can be achieved by improving recruitment practices and providing training that aligns with public service values.

She further adds:

The crucial difference between developed and developing countries that comes out in the literature is that state personnel in the former tend to have stronger professional norms and basic incentives (for example, to show-up to work) compared to state personnel in poor countries. In developing countries, the organization of public sector agencies has allowed private rent-seeking and lacked sanctions, both formal and informal, against poor performance. One study finds that the same doctor performs worse in the public sector clinic than in his own private practice (Das et al., 2016); another finds rampant absenteeism among public sector teachers and health workers (Chaudhury et al., 2006); yet another finds that those who cheat in a lab game are more likely to express interest in a public sector career (Hanna and Wang, 2014); and many others document widespread corruption and bribe-taking behavior. Furthermore, several randomized control trials (RCTs) of implementing high-powered incentives in the public sector find that these incentives work—performance improves significantly (Muralidharan and Sundararaman, 2011; Mohanan et al., 2016; Singh and Masters, 2017)—which might appear contrary to the lessons from theory described above.

However, the paper warns that these technical solutions are not enough. Political factors must be addressed head-on, as they shape both the incentives and the norms that govern bureaucratic behaviour. Reforms targeting only the structure of government agencies without shifting the political incentives may yield short-term results but are unlikely to lead to lasting improvements.

On the influence of politics on bureaucratic norms and state capacity, she argues:

The key difference that explains perverse incentives and lack of motivation in bureaucracies in poor versus rich countries is the nature of politics. For example, Mathew and Moore (2011) provide an account of “deliberate disinvestment” in state capacity in Bihar by leaders who use caste identity as their core political strategy. Beteille (2009) finds that politically connected teachers in India are more likely to be absent from the job. Similarly, in Pakistan, doctors with connections to political leaders are more likely to be absent from public health clinics, and the public officials who manage these doctors are more likely to report political interference when trying to apply sanctions (Callen et al., 2016). Habyarimana, Khemani and Scot (2018) find that the quality of local politicians in Uganda is one of the most robust correlates of bureaucratic productivity in delivering health services in Uganda (along with the presence of local media and voter attachment to national political parties). The politics of vote buying that is widespread in the Philippines is found to be substantially correlated with worse health service delivery and a higher proportion of malnourished children (Khemani, 2015). Conversely, more effective enfranchisement of the poor in Brazil, which was accomplished through electronic voting reforms that reduced the number of invalid votes cast by the poor, is associated with greater public spending on health and improved child health (Fujiwara, 2015). Mobarak et al. (2011) also report evidence of the influence of local politics on health service delivery in Brazil. Political party turnover in Brazil leads to greater replacement of headmasters and teachers, lowering of test scores among children in municipal schools (Akhtari, Moreira and Trucco, 2017).

Role of external development partners

Khemani notes that international development organizations often provide financial resources and expertise but should avoid imposing solutions that overlook local political dynamics. Instead, she suggests that external partners should support locally-driven reforms by investing in knowledge-sharing and information campaigns that enhance transparency and encourage accountability.

International partnerships can play a role in promoting political accountability and public engagement, creating an environment conducive to reform. However, solutions should be flexible, context-sensitive, and grounded in the specific political and cultural realities of the countries they aim to help.

Implications and path forward

Khemani’s paper underscores that state capacity is not merely a technical issue but a deeply political one. The challenges of state-building require navigating entrenched political interests and fostering norms that encourage public service and accountability. Reformers must recognize that shifts in political culture and public expectations are essential for sustainable improvements in state capacity.

For policymakers and development practitioners, the key takeaway is that state capacity requires a multi-dimensional approach. Reforms must balance structural changes with efforts to reshape bureaucratic norms and political incentives. Without addressing the underlying political and cultural factors, technical reforms alone cannot achieve lasting transformation.

In sum, Khemani’s analysis of state capacity offers a holistic view of what makes governments effective. The framework she presents provides valuable insights for policymakers aiming to design more capable and responsive states that are better equipped to meet the needs of their citizens.