Dispatch #96: From bottom-up to top-down: How China and India approach education differently

This dispatch examines the contrasting educational paths of China & India from 1900 to 2018, highlighting how their unique approaches to human capital development have influenced economic growth.

The paper titled Human Capital Accumulation in China and India by Nitin Kumar Bharti and Li Yang comprehensively analyses the educational systems in these two populous nations from 1900 to 2018. The authors explore how historical developments in education have influenced economic growth and inequality, highlighting significant differences in their approaches to human capital accumulation. This dispatch will delve into the paper's major themes, summarizing its findings.

Historical context of education in China and India

Education is a critical driver of long-term economic development. The paper begins by establishing the historical context, noting that both China and India had similar literacy rates of around 20% in 1950. However, by 1990, China's literacy rate had surged ahead, surpassing India's by 25 percentage points. This divergence in educational attainment has been linked to their respective economic trajectories, with China experiencing rapid growth primarily through its manufacturing sector, while India has seen growth driven by services. The authors emphasize that understanding the evolution of education systems is essential for comprehending the broader economic disparities between these nations. They argue that the different paths taken by China and India in developing their educational frameworks have had profound implications for human capital accumulation and economic inequality.

Key findings: Diverging educational paths

1) Bottom-up vs Top-down approaches

Bottom-up approach in China

China's educational expansion began with a focus on primary education, emphasizing mass literacy and basic education for all. This approach involved grassroots initiatives that prioritized enrolling large numbers of children in primary schools, thereby laying a solid foundation for further educational attainment. The Chinese government recognized that a literate population was essential for national development, especially in the context of its economic reforms starting in the late 1970s.

Key characteristics of the bottom-up approach:

Mass enrollment: China achieved significant enrollment rates at the primary level as early as the 1930s, focusing on universal access to basic education.

Sequential development: After establishing a strong primary education base, China progressively expanded middle and then tertiary education. This sequential approach ensured that each educational level was adequately developed before moving to the next.

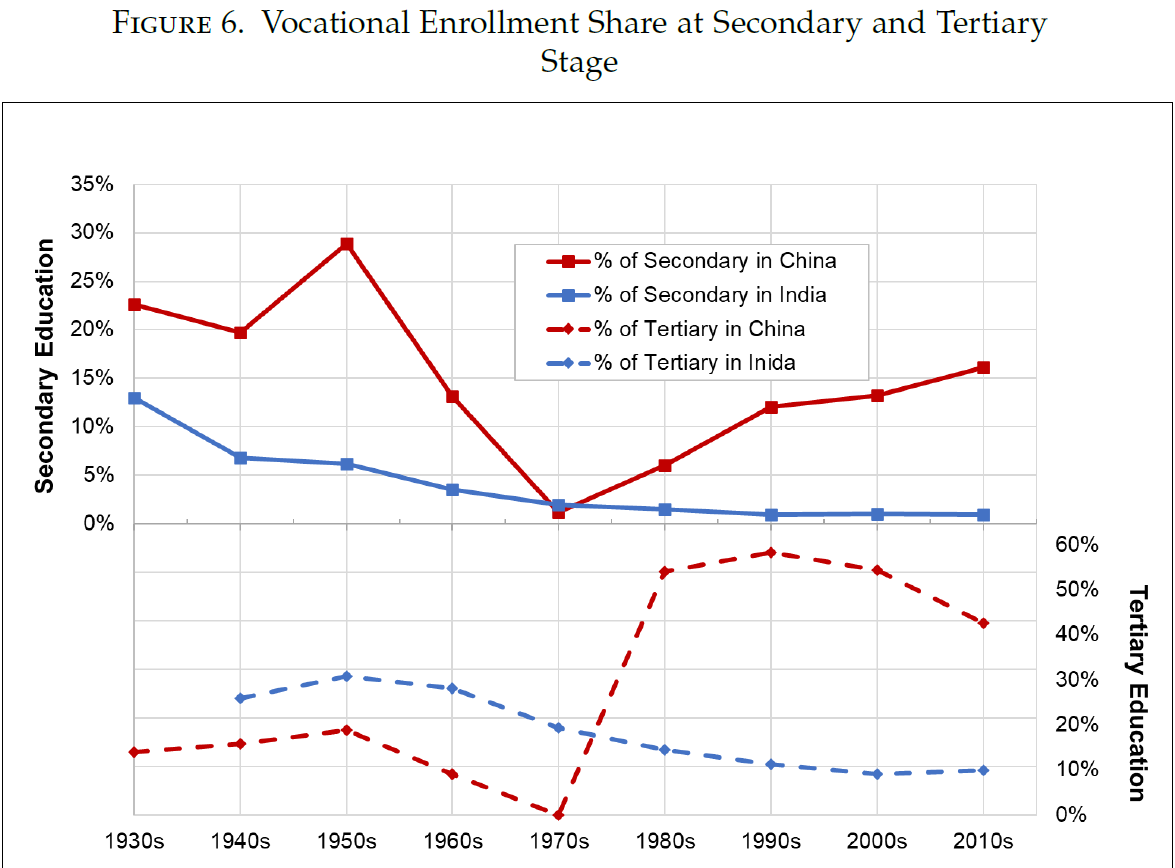

Vocational education emphasis: A substantial portion of students (around 50% at the tertiary level) pursued vocational education, aligning educational outcomes with labour market needs. This focus on practical skills contributed to China's rapid industrialization and economic growth.

Outcomes of the bottom-up approach

Higher human capital accumulation: The structured expansion resulted in higher average years of schooling per cohort. For instance, individuals born in 1962 had an average of 8.9 years of schooling compared to only 3.4 years for their Indian counterparts.

Economic growth: The emphasis on vocational training produced a workforce equipped with relevant skills, facilitating China's transition to a manufacturing powerhouse.

Reduced inequality: While inequality remains an issue, China's educational model has contributed to more equitable access to opportunities compared to India.

Top-down approach in India

In contrast, India's educational expansion has been characterized by a top-down approach, where policies often prioritise higher education over foundational learning. Despite having an earlier start in modern education systems due to British colonial influence, India's focus has been skewed towards elite education.

Key characteristics of the top-down approach:

Higher education focus: India invested heavily in higher education institutions, particularly engineering and management colleges, while primary and secondary education lagged.

Policy implementation: Educational reforms often stemmed from governmental mandates without sufficient grassroots involvement or infrastructure support at lower levels.

Limited vocational training: Unlike China, India has struggled to integrate vocational training into its educational framework effectively. A significant portion of students (60%) pursue traditional degree courses in humanities rather than vocational disciplines.

Outcomes of the top-down approach:

Lower human capital accumulation: The emphasis on higher education without a strong primary foundation led to lower overall educational attainment levels and greater disparities within cohorts.

Increased inequality: The unequal distribution of educational resources has exacerbated wage inequality in India. The paper highlights that while within-group wage inequality is comparable between the two countries, between-group inequality is significantly higher in India due to disparities in educational attainment.

Mismatch with labour market needs: The focus on traditional academic disciplines has resulted in a workforce that may not align well with industry demands, contributing to underemployment among graduates.

Comparative impact on literacy rates

1950s:

China: Approximately 20% literacy rate.

India: Approximately 20% literacy rate.

1970s:

By this time, China's focus on mass primary education had begun to yield results. The literacy rate increased significantly due to its bottom-up approach, which prioritized primary education and grassroots initiatives.

India's literacy rate remained stagnant, primarily due to its top-down approach that emphasized higher education without adequately addressing foundational learning.

1990:

China: By 1990, China's literacy rate had risen to around 65%, reflecting the success of its educational reforms and mass enrollment strategies.

India: In contrast, India's literacy rate was only about 40%, indicating slower progress in expanding educational access and improving literacy levels.

Factors influencing literacy rates

China's bottom-up approach:

China’s educational strategy focused on expanding primary education first, leading to a strong foundation for literacy. The government implemented policies that encouraged mass enrollment in primary schools, resulting in rapid increases in literacy rates.

The emphasis on vocational education also played a role, as it helped align educational outcomes with labour market needs, further promoting economic growth and literacy.

India's top-down approach:

India's focus on higher education without sufficient investment in primary and secondary education contributed to its slower literacy growth. The government prioritized elite institutions while neglecting the need for basic education for the broader population.

This approach led to significant disparities in educational attainment and limited access to quality education for many, particularly in rural areas.

2) Enrollment trends

The paper reveals that China surpassed India in enrollment figures at various educational levels at different times: primary education in the 1930s, middle education in the 1970s, and higher education in the 2010s. This consistent trend indicates that China's focus on mass education has been more effective than India's strategy.

3) Vocational education

Another significant finding is the emphasis on vocational education within China's educational system. China's education system evolved significantly between the 1950s and the 1990s to support its burgeoning manufacturing sector. This evolution was characterized by a strategic focus on vocational education, mass enrollment in primary education, and a gradual shift towards higher education that aligned with economic needs. Approximately 50% of students at the tertiary level are enrolled in vocational programs, which contrasts sharply with India's focus on traditional degree courses—60% of which are in humanities. This disparity has implications for labour market outcomes; vocational training has been linked to better alignment with industry needs and economic growth.

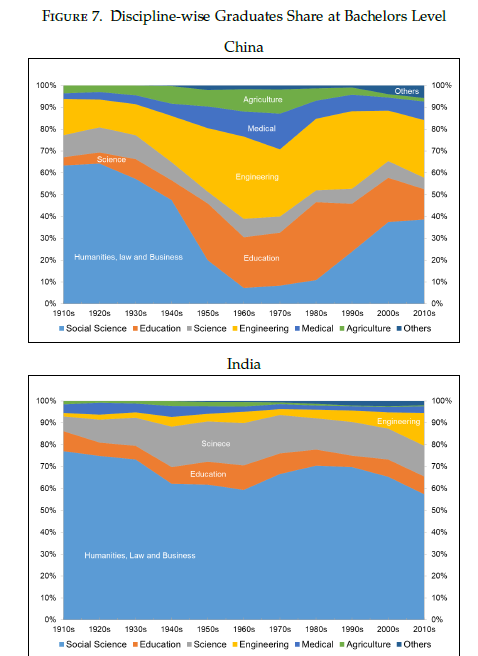

4) Discipline-wise graduates

The paper provides a detailed analysis of the discipline-wise distribution of graduates at the bachelor's level in both countries. This aspect is crucial for understanding how educational policies have shaped China and India's labour market and economic development.

Key insights on discipline-wise graduates

Distribution of graduates by discipline:

In China, there has been a dramatic shift in the distribution of students across disciplines over the decades. Before the 1950s, fields such as arts and law accounted for more than 50% of total enrollments. However, from the second half of the 20th century onwards, there was a significant expansion in engineering and technical disciplines, essential for supporting the manufacturing sector. By the 1980s, there was also an increasing share of students enrolling in law, economics, and management programs.

In contrast, India's discipline distribution has remained relatively stable over time. Since 1897, students in arts and law have consistently constituted more than 60% of enrollments at the bachelor's level. The representation of engineering and technical fields has been much lower than in China, despite India's reputation as a "land of engineers."

Implications for economic development:

The higher share of engineering graduates in China has been linked to its rapid industrialization and economic growth. Engineering and technical education are positively associated with innovation and productivity, which are critical for a manufacturing-driven economy.

In India, the predominance of humanities graduates may contribute to a mismatch between educational outcomes and labour market needs. The limited focus on engineering and vocational training has implications for the country's ability to compete in sectors that require technical expertise.

Vocational education:

As mentioned earlier, the paper highlights that vocational education is a central component of China's higher education system, with nearly 50% of students enrolled in vocational programs at the tertiary level. This focus on practical skills aligns closely with industry demands and has facilitated China's economic transformation.

Conversely, India's vocational education remains underdeveloped, which can hinder its economic growth potential. The lack of vocational training opportunities means that many graduates may not possess the skills needed by employers, contributing to higher levels of unemployment among youth.

Impact on wage inequality:

The differences in discipline-wise graduate distribution also reflect broader trends in wage inequality between the two countries. In India, higher levels of educational attainment do not necessarily translate into better job opportunities or wages due to the oversupply of graduates in non-technical fields.

In China, the integration of vocational training within its educational framework has contributed to lower wage inequality by providing a workforce that meets industry needs more effectively.

Policy implications

The findings of this paper have important implications for policymakers aiming to enhance human capital development. The authors suggest that understanding the historical context and current dynamics of educational systems can guide resource allocation decisions. For instance:

Investment priorities: Policymakers may need to reconsider whether to allocate more resources to primary or higher education based on observed outcomes.

Vocational training: Given China's success with vocational education, India might benefit from expanding its vocational training programs to better align with labour market demands.

Equity focus: Addressing disparities in educational attainment is crucial for reducing wage inequality. This could involve targeted interventions aimed at underrepresented groups.

Conclusion: Lessons learned

In conclusion, the paper provides valuable insights into how different educational strategies can shape economic outcomes and social equity. The contrasting paths taken by these two nations serve as a powerful reminder of the importance of context when designing educational policies. As we look ahead, it is clear that investments in human capital will remain a cornerstone for sustainable development. By learning from each other's experiences—China's focus on mass vocational training and India's need for equitable access to quality education—both countries can continue to evolve their educational frameworks to meet future challenges. This analysis not only enriches our understanding of educational policy but also underscores the interconnectedness of education, economic growth, and social equity—elements that are vital for fostering inclusive development globally.

I met Fei Xiaotong - one of many who were made to disappear and then came back into circulation in the 1980s - at the Good Society Conference in 1993 - he said that the annihilation of the Gang of Four freed China from the ideological straitjacket and ensured that the revived focus on research & education led to the annihilation of poverty

Of course quite silent on the completely destruction of higher education institutions in China during the “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution”! At Binghamton, Mark Selden and Bill Hinton (coming from Cornell) had quite a few Chinese graduate students in the 1980s, whose parents had disappeared during the CR on account of their academic occupations. A lot of credit must be given to Deng et al for beginning the transformation of China into the education & research powerhouse it is today