Dispatch #97: Lessons from the South- How Sri Lanka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu achieved human development

This dispatch explores the interconnected development journeys of Sri Lanka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu, highlighting how these regions achieved remarkable human development.

I recently visited Sri Lanka, and during my trip, I became deeply fascinated by the country’s development narrative. This curiosity led me to explore Swati Narayan's insightful book, Unequal. The book discusses the concept of ‘Southern Supermodels,’ focusing on the development trajectories of Sri Lanka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu. In this dispatch, I will delve into the key themes from the book, highlighting how these regions have achieved remarkable human development despite varying economic contexts.

Historical context and development models

Sri Lanka and the southern Indian states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu share profound historical, cultural, and social ties. Their development models have often been compared due to their impressive human development indicators, which rival developed countries despite modest per capita incomes. The term ‘Southern Supermodels’ aptly describes these regions' successes in achieving high human development outcomes through unique strategies that prioritize social equity over rapid economic growth.

Key factors contributing to the development

Social reform movements:

Social reform movements have significantly bridged inequalities in these regions. Kerala’s history is marked by radical social movements to dismantle caste discrimination and promote education among marginalized communities. The impact of these movements has been profound, leading to significant changes in social structures and access to resources. The anti-caste movements in Kerala, particularly those led by figures like Sree Narayana Guru and Mahatma Ayyankali, were instrumental in challenging entrenched social hierarchies. These movements not only advocated for educational rights but also fostered a sense of collective identity among marginalized groups.

The social reform movements in Tamil Nadu have played a pivotal role in shaping the state's socio-economic landscape, addressing deep-rooted inequalities, and promoting human development. These movements emerged as responses to caste discrimination, economic exploitation, and social injustice, significantly transforming the lives of marginalized communities. One of the most significant social reform movements in Tamil Nadu is the Dravidian Movement, which emerged in the early 20th century. This movement sought to challenge the dominance of Brahmins and promote the rights of non-Brahmin communities. The social reform movements also mobilised various caste groups to demand their rights and improve their socio-economic conditions.

Scheduled Caste movements: Organizations like the Scheduled Caste Federation were established to advocate for the rights of Dalits. These movements aimed to secure political representation, access to education, and employment opportunities for marginalized communities.

Temple entry movements: Similar to Kerala’s temple entry struggles, Tamil Nadu witnessed several movements advocating for the right of Dalits to enter temples. These movements challenged caste-based restrictions and sought to promote social integration.

Similar to Kerala and TN, various movements aimed at dismantling caste discrimination and promoting education among marginalized communities have been crucial in Sri Lanka. The influence of social movements has allowed marginalized groups to challenge the status quo and demand greater equity.

The Colebrook-Cameron Reforms of 1833 was a pivotal moment in the history of Sri Lanka (then known as Ceylon), marking a significant transformation in its administrative, judicial, and social frameworks under British colonial rule. The reforms were initiated by the Colebrook-Cameron Commission, which was tasked with investigating the existing systems of governance and proposing comprehensive changes to improve efficiency and equity in the administration of the island.

Some of the key features of these reforms were:

Administrative unification: Before the reforms, Ceylon was divided into separate administrative regions based on ethnic and cultural lines. The Commission proposed a unified administrative structure, dividing the island into five provinces. This aimed to reduce ethnic divisions and promote a sense of national identity.

Judicial system overhaul: The reforms established a single judicial system based on English common law, replacing the fragmented legal framework that included various traditional and colonial laws. This move was crucial in providing equal rights before the law for all citizens, regardless of their ethnic background.

Legislative Council formation: The creation of the Legislative Council in 1833 marked the beginning of representative governance in Ceylon. This council included both official and unofficial members, with representation from local communities (Sinhalese, Tamils, and Burghers), thereby giving a voice to Sri Lankans in legislative matters.

Economic reforms: The Commission recommended significant changes to land tenure systems and proposed the abolition of the 'Rajakariya' system, which enforced compulsory labour. These economic reforms aimed to encourage agricultural productivity and secure property rights for landowners.

Educational advancements: The establishment of English medium schools laid the groundwork for Western-style education in Ceylon, promoting literacy and modern educational practices among the local population.

The Colebrook-Cameron Reforms significantly transformed Sri Lankan society by laying the foundations for modern governance and legal systems. They marked a shift from mercantile sovereignty to a more structured form of colonial governmentality, which sought to regulate various aspects of daily life, including economic activities and cultural practices. The reforms also contributed to the rise of a more organized Sinhalese Buddhist nationalism, as they provided a framework for local communities to engage with colonial authorities while advocating for their rights and interests. This period saw increased political awareness among different ethnic groups, leading to future demands for greater autonomy and representation. The early 20th century saw the rise of movements advocating for women's rights and social justice. The Ceylon Women’s Franchise Union, for instance, played a pivotal role in pushing for women’s suffrage and empowerment.

The author explains:

The advances of the Southern Supermodels are often credited to the greater freedoms enjoyed by women. Women’s agency is usually displayed in their ability ‘to earn an independent income, to work outside the home, to be educated, to own property’. The ability to vote and be elected to political ofce are also equally important. Each of the three regions faced their own unique challenges in bringing women to the forefront. My research highlights only three iconic turning points. Kerala’s nineteenth-century Channar Upper Cloth Revolt for women to earn the right to dignied clothing, Sri Lanka’s twentieth-century suffragette movement for women’s right to vote and Tamil Nadu’s Dravidian Self-Respect Movement, with women’s emancipation at its core.

Investment in education:

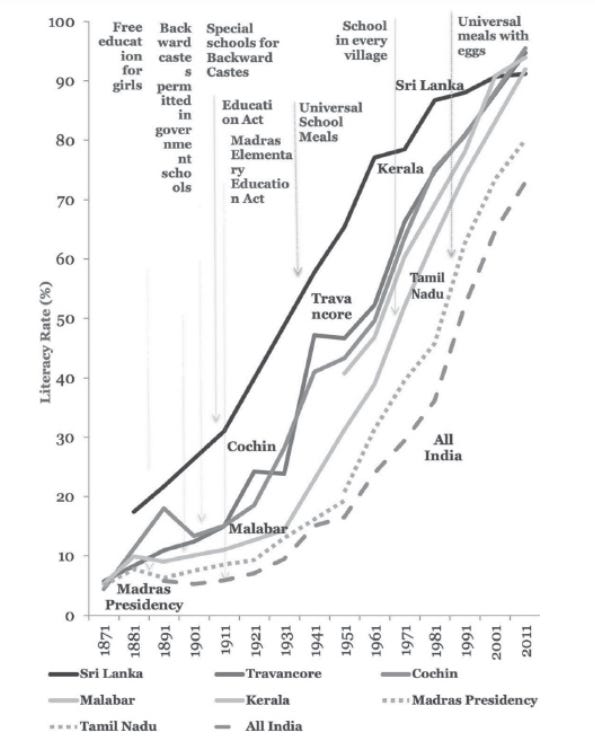

Education has been a cornerstone of development in these regions. Both Kerala and Sri Lanka have prioritized education since the early 20th century, resulting in high literacy rates and improved health outcomes. The anganwadi system in Kerala and Tamil Nadu has been pivotal in providing early childhood education and nutrition. These programs ensure that children receive adequate nourishment and educational support from a young age, contributing to better long-term outcomes. Sri Lanka has made significant educational strides since its colonial era, where British policies laid the groundwork for a more inclusive education system. By focusing on universal primary education early on, Sri Lanka achieved impressive literacy rates that contributed to its success in human development.Swati Narayan further explains:

The southern trio also share three characteristics. Firstly, they tend to invest more as a proportion of GDP in ‘equity enhancing’ policies for education, healthcare, nutrition and other essential services. In Sri Lanka, between 1959 and 1968, for example, expenditure on primary and secondary education was one of the highest in Asia. More than 4.5 per cent of GNP was spent to achieve a literacy rate of 85 per cent. The government funded compulsory education, food subsidies and free healthcare through heavy taxation on the export of plantation crops. Secondly, the southern trio also focus more on primary rather than tertiary levels of care. In healthcare, for example, prevention is often better and cheaper than cure in hospitals. Kerala’s most impressive public health programmes focused on immunisation. Smallpox vaccination began in 1879 in Travancore and reached the entire population within six decades. Lastly, the three regions have also effectively tapped into synergies between health, nutrition and education. During the Second World War, for example, apart from school meals, ‘fair price’ ration shops were also established in Kerala, a food-decit state.

Swati Narayan concludes by asserting:

The Southern Supermodels analysis showcases that Sri Lanka and the Indian states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu have had long periods of accelerated human development, even in times of stagnant economic growth. Their key similarity lies in their efforts to combat multidimensional inequalities—with investments in universal public services, progressive social movements, women’s agency and cultural ties—in the course of more than a century.

Sri Lanka's economic growth story is marked by significant achievements, yet it is not without its share of challenges and complexities.