Dispatch #54:Financing healthcare in India

In this dispatch we will look at the public financing of healthcare in India and will also see the health financing transition due to economic growth of a country

Health financing is broadly concerned with how financial resources are generated, allocated and used to generate health services. Financial resources in any healthcare system are generated by pooling revenues through taxes, both direct and indirect. Resources are allocated at different levels of health systems- primary, secondary and tertiary; and they are used by several care providers or utilized in purchasing medicines, equipment, infrastructure and human resources.

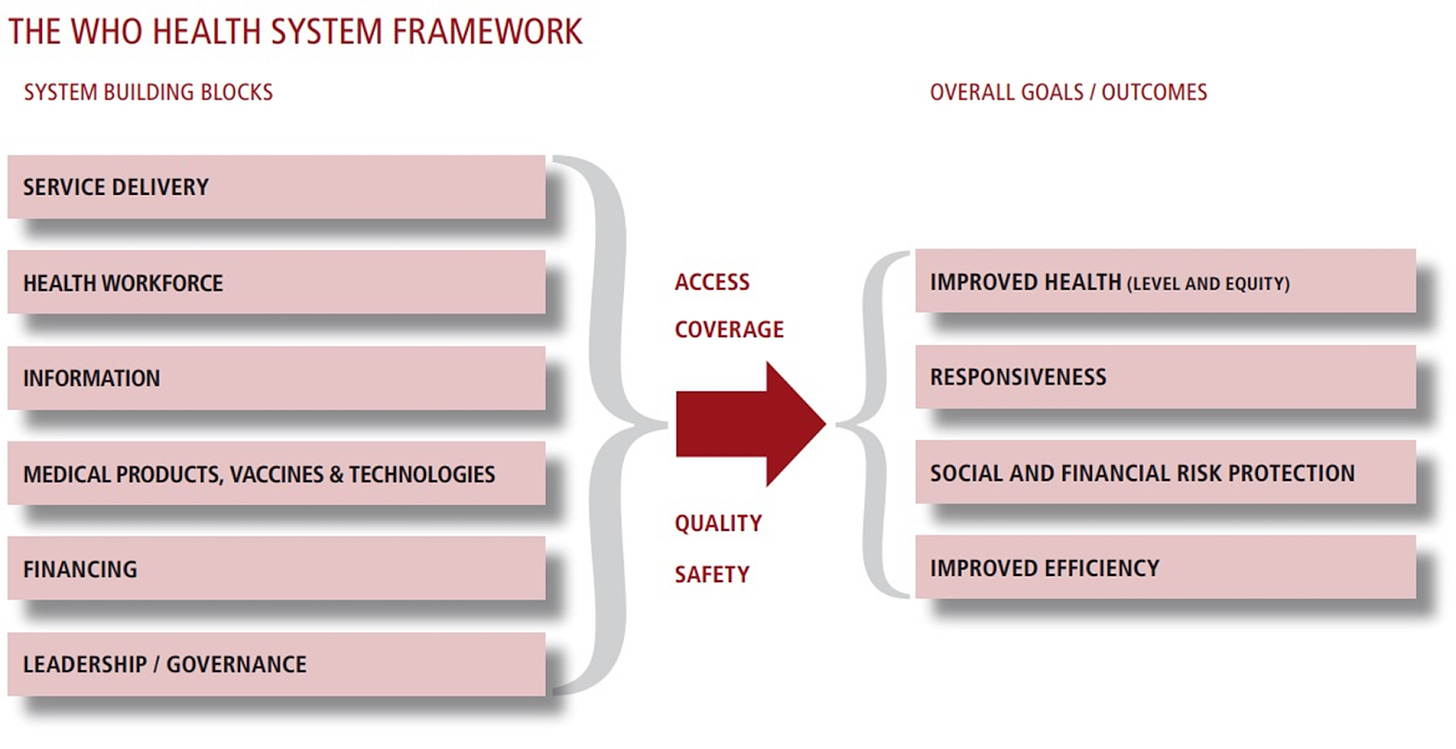

Health financing is one of the most integral parts of the WHO Health System Framework that comprises ‘System Building Blocks’ that act as inputs and ‘Overall Goals/Outcomes’ that act as outputs.

The WHO document on the framework says:

The six building blocks contribute to the strengthening of health systems in different ways. Some cross-cutting components, such as leadership/governance and health information systems, provide the basis for the overall policy and regulation of all the other health system blocks. Key input components to the health system include specifically, financing and the health workforce. A third group, namely medical products and technologies and service delivery, reflects the immediate outputs of the health system, i.e. the availability and distribution of care.

-WHO Health Systems Framework

One of the key goals of any health financing system is to protect citizens from financial risks due to adverse health episodes. Hence pooling of financial resources and utilizing them in a pre-paid manner is regarded as the hallmark of an effective health system. This also brings health financing closer to the larger project of Universal Health Coverage (UHC). UHC is a policy commitment, under the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 2030. The UHC commits to provide good quality and effective health services (preventive, promotive, curative, rehabilitative and palliative) while also ensuring that there are no financial barriers to access these services. The UHC is not only about the access of health services but also financial protection from catastrophic health expenditure.

In their latest paper titled ‘Redistribution and the health financing transition’, K Srinath Reddy (PHFI) and Ajay Tandon (WB) have to say this about the UHC and health financing:

Hallmarks of ‘high-performing’ health financing systems for UHC can be characterized as those where financing levels are adequate, prepaid funds are pooled in a sufficient way to spread the financial risks of ill-health, and spending is efficient and equitable to assure desired levels of effective service coverage and financial risk protection for all people, both with resilience and sustainability.

-Reddy and Tandon

The financial protection, that the UHC advocates, comprises risk pooling through a prepaid mechanism that gets sourced by taxes. This acts as an antidote to the Out Of Pocket Expenditure (OOPE). There is no risk protection in OOPE and the households have to bear the costs of adverse health episodes. The compulsory prepayment in the form of taxes etc. creates a pool of financial resources that cross-subsidizes from the healthy to sick without inflicting any catastrophic expenditure.

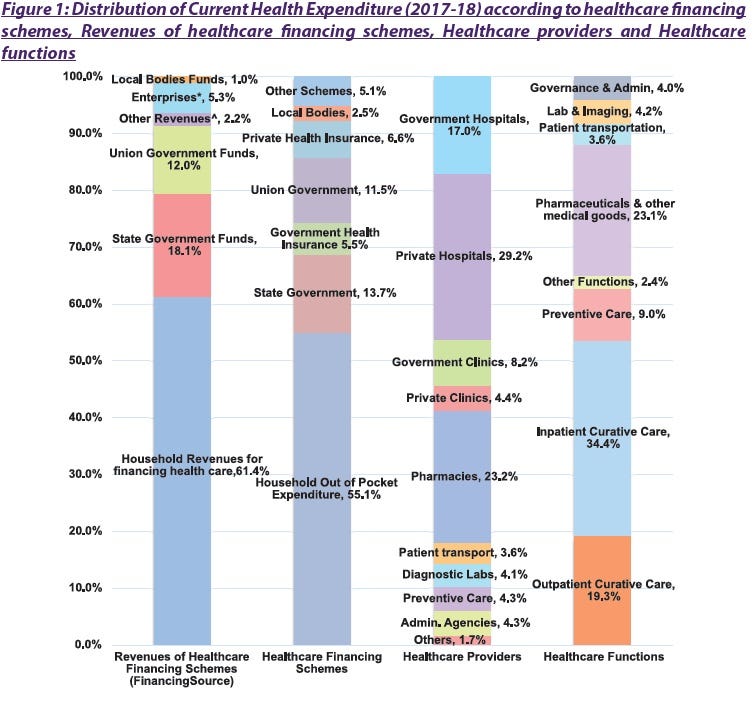

According to the latest report on the National Health Accounts (2017-18), nearly 61% of financial sources come from households in India, which contributes to nearly 55% of OOPE. A significant proportion of the care providers are in private space- private hospitals (29.2%), private clinics (4.4%) and pharmacies (23.2%).

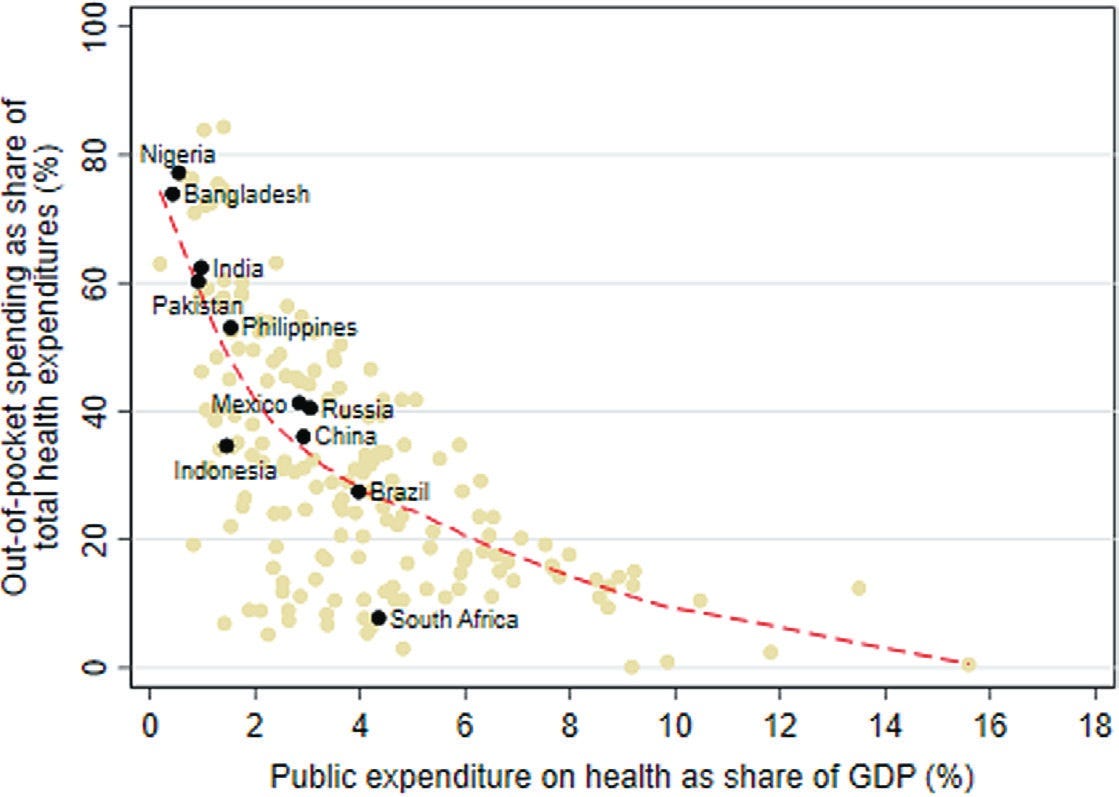

As mentioned earlier, a robust public financing of the healthcare system through prepayments could be an effective way to address the problem of the OOPE, however, there is an inverse relationship between the OOPE and the public financing in most of the countries in the world. ‘How’ the public funds are expended is also important. The binary understanding of public finance and OOPE needs to be changed with a nuanced understanding of how the funds are utilised, what services are being bought from these financial sources, whether equity is being considered while financing healthcare etc.

Reddy and Tandon write:

OOP spending remains the largest source of financing in several large developing countries including Nigeria, Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, and the Philippines. Countries that are closest to attaining UHC have OOP spending levels that are usually less than 15%-20% of total health spending (a threshold benchmark recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO); as, eg, is the case in high-income Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries) or where OOP spending–despite being higher than the 15%-20% threshold–is largely incident on well-off segments of the population and therefore is no longer a significant risk factor for impoverishment (eg, in Malaysia and Sri Lanka).

-Reddy and Tandon

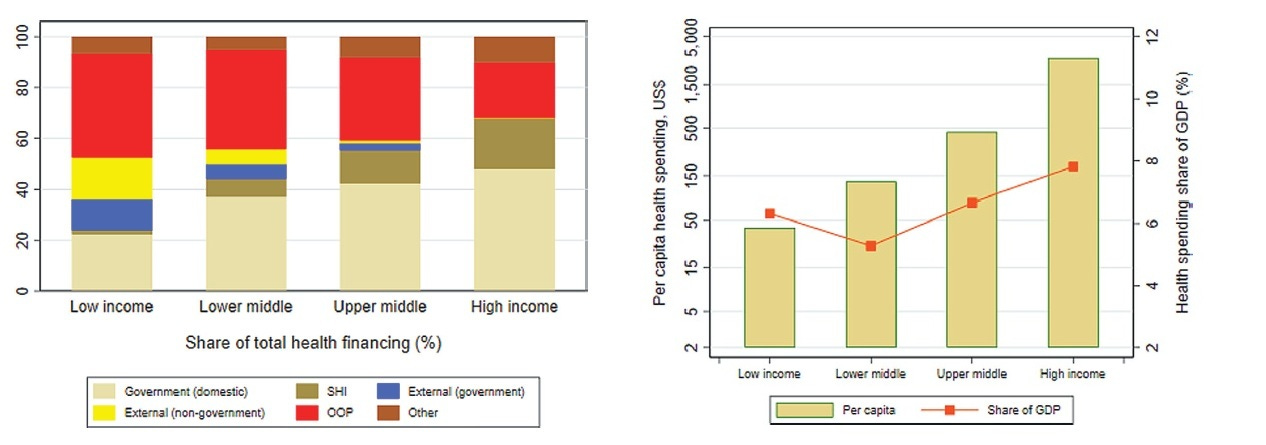

The economic growth of a country and public financing of the healthcare system are also interrelated. With economic growth, countries undergo two kinds of transitions - demographic transition (in terms of rise in life expectancy, decline in mortality, decline in fertility and higher prevalence of communicable diseases) and health financing transition (with increase in government revenues, the health spending increases and OOPE decreases). Therefore, with growing national income, health spending also increases generally. In the paper they have explained the health financing transition of high-income, mid-income and low-income countries. While the high-income countries have low OOPE, low-income countries have high OOPE since they cannot finance health.

Reddy and Tandon further highlight:

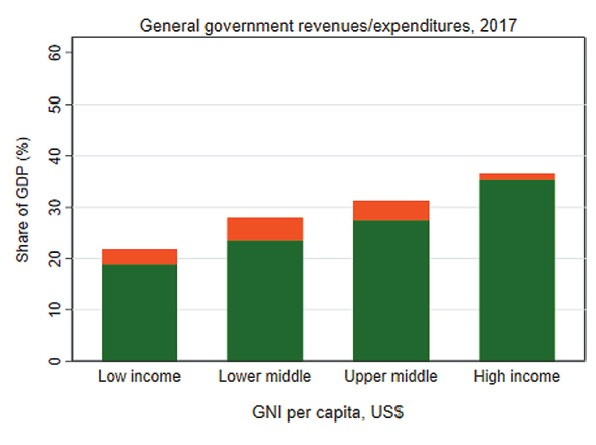

The health financing transition is evident in cross-country data: low-income countries (LICs) spent an average of US$37 per capita in 2017, or 6.2% of GDP. Richer countries spent far more: lower middle income (LMI) countries spent US$128 (5.3% of GDP), upper middle income (UMI) averaged US$449 (6.3% of GDP), non OECD high-income countries (HICs) spent US$1293 (5.4% of GDP), and OECD HICs spent US$3733 (9.6% of GDP). Also, the sources of health financing change with national income: HICs financed most of health spending vis public sources of finance – a mixture of domestic general government revenues and SHI contributions – whereas lower income countries were predominately financed from OOP sources.

-Reddy and Tandon

A country’s ability to raise revenues to publicly finance its healthcare system depends upon 3 factors:

Economic growth

Revenue raising capacities of the government

Prioritization of health by the government

As explained earlier, high-income countries with high economic growth are in the position to finance healthcare, thus reducing the dependency on OOPE. However, India is an exception.

Reddy and Tandon argue:

India is a case in point: although levels of public financing for health remain far below those expected for its income level, relatively high economic growth rates have resulted in almost a tripling in real public financing for health in per capita terms since 2000.

-Reddy and Tandon

Low income countries have low levels of revenue that can be utilized to finance healthcare. The reasons being high levels of poverty, high rates of informality and weak state capacity to collect taxes. The authors of the study have claimed that ‘whereas in HICs, general government revenues were more than 35% of GDP, this number was less than 20% in LICs’.

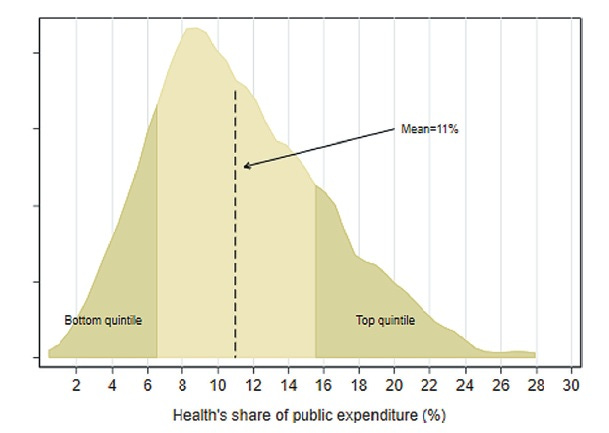

Finally, to understand whether health is a priority of any government, one of the proxies is the share of public spending that goes into healthcare. The average share of health in public spending is around 8%, claim Reddy and Tandon.

They observe:

There are large and notable variations across countries: health accounts for less than 3% of public expenditures in Venezuela, Iraq, and Equatorial Guinea to almost 30% in Costa Rica. Countries where health’s share is below 6% (such as Bangladesh, India, Myanmar, Cameroon, Egypt, Lao PDR, Nigeria, Afghanistan, Egypt, Haiti, Cambodia, Cote d’Ivoire, and Uganda) are in the bottom quintile whereas those where health’s share is greater than 15% (such as Peru, Tanzania, Sierra Leone, Malawi, Rwanda, Madagascar, Guatemala, Costa Rica, and Colombia) are among the top quintile globally. In comparing prioritization across countries, it is important to note that the relationship between health’s share of public expenditure and public financing for health as a share of GDP is not monotonic since the size of public expenditures are different across countries. A country such as Cuba has a lower health share of public expenditures relative to Iran but a higher share of GDP because its size of public expenditures is higher. Indonesia, on the other hand, has roughly the same health share of public expenditures as Bhutan but is lower as a share of GDP because the size of public expenditure in Indonesia is lower than that of Bhutan’s.

-Reddy and Tandon

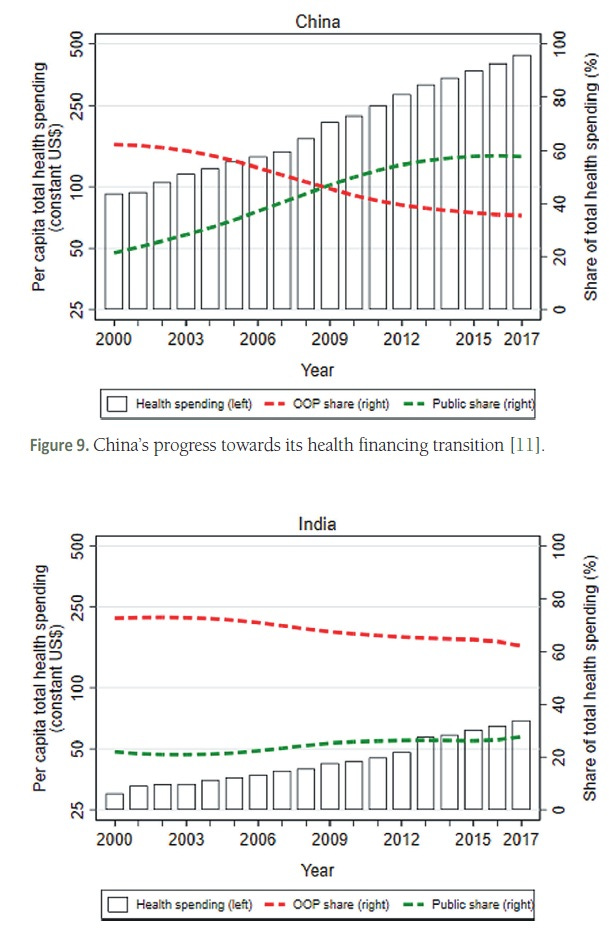

The authors have also done an excellent comparative analysis of health funding transition in China and India. While in China, with rise in national income and economic growth, the public spending on health increased and thus the OOPE declined over the years. This did not happen in India where the public spending on health did not increase significantly since the budgets never prioritised health spending and therefore the OOPE remained high.

Most of the supply-side systems of public financing of health depend upon the revenues from the government. However, there are a few challenges in such systems. First, there could be inter-regional disparities within a country with respect to the coverage of health services. Chances are high that under-served regions are perennially neglected. Second, under-financing could lead to ‘exit’ to the private sector, poor quality of services and fragmentation of services.

Recently, India has started to emphasize on demand-side solutions like health insurance. Ayushman Bharat is the flagship insurance scheme by the Government of India. Even the demand-side solutions like insurance can run into difficulties such as discrepancy in benefits packages, poor quality of services and payment delays.

While India needs a financing mechanism that incorporates both demand and supply side requirements, the coverage of quality public health services could be a good starting point. In their latest article, Reddy and Sarit Kumar have argued that:

Besides aiming for a further reduction in OOPE, we must also increase the level of service coverage. While coverage by India’s health services has been estimated to be 55%, other countries which have adopted a predominantly tax based funding model of UHC have done better. Thailand, for example, has service coverage of 82%, while Sri Lanka has 66%. Tax-based funding translates to higher financial protection and better service coverage, while private purchase of health services escalates OOPE while shrinking service coverage. India’s path to UHC lies in higher public financing.

-Reddy and Sarit Kumar