Dispatch #18: Aisi Taisi Democracy?

In this dispatch we will review the academic literature on Indian democracy and her development pathway in the last 70 plus years

Recently someone just gave a silly comment that too much democracy in India is holding back big ticket reforms. I don’t want to comment on the imbecility of the comment. What I am going to do in this dispatch is enlisting some academic literature on the correlation between democracy or democratic institutions on the economic development of a country.

1) Dynamism with Incommensurate Development- The Distinctive Indian Model:

This is a brilliant paper by Arvind Subramanian and Rohit Lamba to understand why a democratic country like India that was poor and literate at the stroke of the midnight gave universal franchise and hence political rights to the citizens and how it traversed a very different development path.

There are several gems in the piece and the best way to enjoy this paper is to read the articles in the reference also.

I have earlier written about the themes in the paper in previous dispatches:

Precocious Development- Part 1

Precocious Development- Part 2

Precocious Development- Part 3

The authors write,"Political institutions and economic development are strongly correlated. One direction of causation owes to the “modernization hypothesis” of political science: the empirical regularity that countries start democratizing as their incomes grow and sustain democracy only at higher levels of income.4 India has famously defied this hypothesis. Political scientists often describe as an anomaly how India has managed to sustain a democracy under inhospitable conditions of low income and literacy, a predominant rural economy, and major social cleavages—especially once the factor of caste is taken into account. Varshney (1998) provides a thoughtful analysis of democracy in India as a puzzle for most standard theories of political economy.”

2) Why Does the Indian State Both Fail and Succeed?

This paper by Devesh Kapur does not directly delve into the democracy-development correlation but leaves the reader with several thoughts on Indian development journey. Kapur picks up the thread on ‘India as a flailing state’ left by Lant Pritchett. Kapur says that Indian state is good at episodic activities like elections, Kumbh etc. but fails at quotidian activities like providing health and education. This paper is interesting to learn the weakness of the Indian state. Indian state has not been able to make a dent when it comes to sticky issues like caste and gender.

Kapur writes, “India’s democratic persistence has defied theorizing about democracy. One well-regarded study on the relationship between democracy and development found that India was a major outlier given its low level of income and literacy and high levels of ethnic and religious conflict: “India was predicted a dictatorship during the entire period … the odds against democracy in India were extremely high” (Przeworski et al. 2000). In particular, when India’s constitution guaranteed universal franchise for men and women in 1950, real GDP per capita in India was lower than what Western democracies like the United Kingdom, United States, Sweden, or the Netherlands had a century or more before (when of course universal franchise was unknown). India adopted the universal franchise when literacy was barely 18 percent and life expectancy was just 32 years.

In addition, national-level democracy and the universal franchise in India arrived all at once in 1950. The expansion of the franchise in most nations of the West was much more gradual, from male property holders to all men to women and later (in some cases) to members of marginalized communities. In countries of East Asia, there was a clear sequencing with universal franchise following a protracted process of economic development and state-building. Most Latin American countries experienced periodic reversals in democracy even as their economies grew. In both Western democracies and East Asia, universal franchise came after the state had laid the foundations of public goods in education and health, and the structures of the welfare state were built gradually on these foundations.”

Kapur suggests 3 reasons why Indian democracy, in some ways, is responsible for this mixed behavior of the Indian state.

First, precocious democracy tends to militate against the provision of public goods in favor of redistribution. Countries that experienced economic development prior to the transition to democracy also tend to adopt democratic institutions that constrain the confiscatory power of the ruling elite. However, when countries pursue democracy prior to economic development, the democratic institutions adopted enhance the redistributive powers of the state. For related reasons, precocious democracy contributes to weak public good provision. We suggested earlier that being a “premature” democracy appears to have reduced India’s ability to raise revenues compared with other democracies, further undermining its fiscal ability to finance public goods. By not providing public goods before shifting to redistribution, the Indian state weakened the legitimacy and trust to create a virtuous circle that could strengthen the social contract between citizens and the state. This has led to “exit” (in the sense of Hirschman): India’s middle class, feeling that it has not received enough from the state by way of public goods, exits in favor of private provision and is also reluctant to pay taxes. This further undermines the state’s legitimacy and capacity (reflected in the low level of taxpayers in India). In an Indian twist to these pathologies, exit and lack of trust and weak fiscal ability are particularly acute at lower levels of government, which have the primary responsibility for delivering key services such as health, education, water, and sanitation. There is a general unwillingness on the part of lower levels of government to raise revenues and local taxes (such as those on property)—a problem of being closer to the people. This creates a vicious cycle of weak delivery leading to exit, undermined legitimacy, fewer resources, back to weak delivery. Redistributive pressures can also explain variance in regulatory effectiveness. The electricity sector is a clear example where politicians press to keep charges for farmers and households low and attempt to cross-subsidize by charging higher for commercial and industrial units, creating severe distortions in the sector. Second, a precocious democracy with electoral mobilization along social cleavages favors creation of narrow club goods. A central puzzle concerning the poor provision of basic public services in India is seemingly weak demand in an otherwise flourishing electoral democracy. If politicians respond to voters, then why have voters not demanded basic public services such as education, health, water, and sanitation? On this point, explanations seek recourse to the implications of India’s social heterogeneity, especially in a ranked society. Politicians persist in relying on targeted transfer programs and subsidies. Poor farmers might prefer targeted transfers rather than public services such as education because farmers often have high discount rates. Alternatively, politicians might provide “private” public goods such as housing or other material inducements that target particular individuals and small groups of people as opposed to the provision of public goods through institutional means. This behavior is partly due to social cleavages and partly to a lack of credibility of political promises to provide broad public goods (as opposed to private transfers and subsidies). Electoral competition therefore revolves around distributing public resources as “club goods”—goods with excludability characteristics—rather than providing public goods to a broad base. Again, those in the middle and upper classes will often choose to exit from the system, preferring market solutions rather than poor quality and unreliable public services, further reducing pressures to change the system. A third way in which precocious democracy can weaken state capacity is that an imperfect democracy with noncredible politicians will tend to emphasize the provision of goods that are visible and can be provided quickly, like infrastructure, over long-term investments, like human capital or environmental quality. This pattern relates to the signaling problem facing noncredible politicians in an electoral democracy and the politics of visibility. There is a bias towards tackling famines over addressing malnutrition because the former are more visible. There is also a bias towards public goods where quantity is more salient than quality. While this pattern may hold in many democracies, Indian democracy might be particularly susceptible because of lower levels of literacy and social cleavages where the politics of visibility and “signaling” to specific groups becomes more salient.

3) Does democracy cause growth?

In this article, Acemoglu, Robinson, Suresh Naidu and Pascual Restrepo argue that countries who have switched from non-democracies to democracies achieve about 20% higher GDP (Gross Domestic Product) per capita in the long run (or roughly in the next 30 years).

The authors write, “When we disentangle what components of democracy matter the most for growth, we find that civil liberties are what seem to be the most important. We also find positive effects of democracy on economic reforms, private investment, the size and capacity of government, and a reduction in social conflict. Clearly all of these channels by which democracy can increase economic growth, and a great deal of further research is needed. Together with our previous work showing that democracy had no effect on inequality, these results suggest the interaction between democratic institutions and the level and distribution of income is more complex than the previous literature suggests.”

In their recent book ‘The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies and the Fate of Liberty” Acemoglu and Robinson have written about that narrow corridor between strong state and strong society where the liberty flourishes and a country becomes prosperous.

It is in this corridor which they call ‘Shackled Leviathan’ a strong state can enforce rule of law and protect private property and a strong society with ‘Red Queen Effect’ can make sure that the state has checks and balances and is accountable to the citizens.

No points in guessing which political system will have strong society.

4) Democratisation and growth:

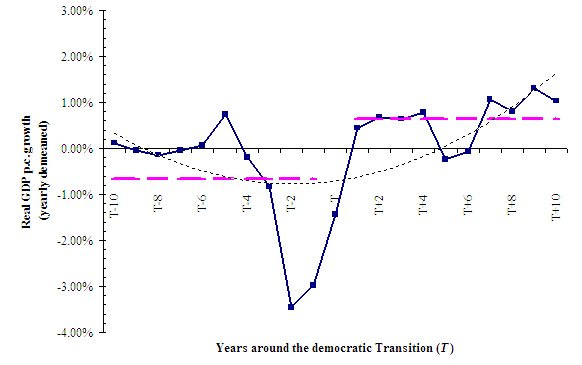

Elias Papaioannou and Gregorios Siourounis have also shown that when countries transition from a non-democracy to democracy then the per capita GDP growth increases. They write, “Our within-country estimates imply that on average democratisations are associated with a 0.5% to 1% increase in annual per capita growth. This result suggests that, besides any moral superiority, democracy can produce significant economic gains.”

They conclude, “Our results suggest that, if anything, the average effect of successful democratic transitions on growth is positive. Our “within” evidence shows that the experience of the past four decades suggests that even moderate political reforms can also bring sizable economic gains. Most importantly, our dynamic analysis suggests that growth is usually volatile and negative during the transition period. Yet after the consolidation of democracy, growth stabilises at a higher rate. This J-shaped pattern accords with F.A. Hayek’s (1960) idea that the ‘as is true of liberty, the benefits of democracy will show themselves only in the long-run, while its more immediate achievements may well be inferior to those of other forms of government.’ "

5) Why Democracy Survives?

In this classic essay, Ashutosh Varshney talks about four aspects as to why democracy survived in India at a low per capita income, a phenomenon that defied modernization hypothesis. These four aspects are historical, economic, ethic configuration and political leadership.

Varshney begins the essay by writing, “Predictions of an imminent collapse of India's democracy have continued since the 1960s. When Prime Minister Indira Gandhi suspended democracy in June 1975 and declared a state of emergency, it seemed that India was finally starting down the path that most of the world's poorer democracies had already traveled. Yet democracy returned 18 months later, and emergency rule proved to be a conjunctural aberration rather than an emerging structural trend. To be sure, danger signs remain. When unpopular ruling parties are thrown out, hope that the new incumbents will govern wisely and well too often gives way quickly to anguish, marked by troubling questions. How long can democracy survive if public trust in India's political leaders continues to decline? How long will short-term benefits--rather than long-term insight--determine the behavior of politicians? Scholars speak of India's democracy as ungovernable, and clearly its health is not what it was in the 1950s and 1960s. But one should not expect a textbook model to work if there has been a serious rise in political participation and a near-breakdown of the caste hierarchy that long acted as the glue of the social order. Indeed, rising participation by once-marginal groups such as the "lower" castes is, if anything, a sign of how much the democratic process has succeeded. Rising political participation, its desirability on grounds of political inclusion notwithstanding, nearly always comes at the cost of disorder. Therefore, the yardsticks for judging India's democratic health today should not be derived from the glory days of the 1950s. "Lower" castes, tribes, minorities, women, and citizens' groups are all exercising their democratic rights to a degree that was unheard of in the 1950s and 1960s. That India still practices democracy is in and of itself unique, and theoretically counter intuitive.”

These arguments are further explained in his book Battles Half Won.

Here is a brilliant talk by Arvind Subramanian on a similar theme.