Dispatch #39: What India can learn from these countries about pandemic management?

This is a curation of Vox's 'The Pandemic Playbook' that enlists strategies of six countries that successfully managed the pandemic and their economies

As India’s Covid-19 management and vaccination policy is bungling, it’s high time we look at the successful strategies adopted by other countries in managing the pandemic.

Vox has just published ‘The Pandemic Playbook’ in which they have highlighted the success factors of the Covid-19 management strategy of 6 countries- South Korea, Germany, Vietnam, United Kingdom, Senegal and United States.

In this dispatch I have synthesized the strategies adopted by South Korea, Germany and Vietnam.

South Korea- Test, Trace, Isolate

It was this simple protocol that South Korea adopted in February 2020, at the very outset of the outbreak, that helped it keep the daily confirmed cases to as low as 700 as compared to the US (around 60,000 daily cases) and India (around 3,50,000 daily cases).

South Korean officials made a plan. They needed to test as many people as possible, as quickly as possible, to figure out how bad the outbreak was. Then they had to find out who might have come into contact with the infected people. And they needed all of those people — both the infected and the potentially exposed — to isolate themselves to prevent the virus from spreading any further.

It was a three-step protocol: test, trace, and isolate. And it worked. Within a week of Patient 31’s diagnosis, the country was performing the most Covid-19 tests in the world; it implemented perhaps the most elaborate contact tracing program anywhere; and it set up isolation centers so thousands of patients could quarantine.

As other countries saw their outbreaks spiral out of control, measures like these helped South Korea keep Covid-19 in check. On March 1, South Korea had about 3,700 confirmed cases; Italy, the first hot spot in Europe, had 1,700 and the US had just 32 cases, though its dismal testing meant the virus was likely spreading unsurveilled. By the end of April, Italy had topped 200,000 cases; confirmed cases in the US were already above 1 million. South Korea still had fewer than 11,000. Adjusted for population, South Korea’s first wave of coronavirus cases was about one-tenth as big as that in the United States.

I wrote about South Korea’s strategy to flatten the curve, last year.

The epidemic preparedness and response framework in South Korea comprised of these essential steps, which its government aggressively pursued:

1) Detection

2) Containment

3) Treatment

Detection: As soon as few cases were detected in South Korea in January, the government sprang into action. The Korean Center for Disease Control was already receiving viral specimens from China to develop diagnostic tools. With cases rising in February, the government roped in the private sector to develop diagnostic tools and reagents on large scale. After ramping up the testing capacity, the government turned its focus towards screening. Drive-through testing and phone-booth style walk-in testing centres managed to collect samples efficiently for testing.

Containment: The Korean government transformed public facilities and training centres of private companies like Samsungand LG into isolation wards. The scale and the pace with which these temporary wards were set up helped admit thousands of people in the month of March. Contact tracing was aggressively done by the Korean government. After the outbreak of MERS, the legal structure is such that the government can use private data of the citizens to trace the spread of the virus. In Korea, data form credit card transactions, GPS data and CCTV footage were used for contact tracing.

Treatment: The Korean administration focussed its interventions on high-risk groups such as people older than 65 years, people having chronic diseases, pregnant women etc. Because of the shortage of beds the health officials developed a triage system using a Brief Severity Scoring System to classify patient illnesses as mild, moderate, severe, or critical. Mildly ill patients were sent to community treatment centres where they were closely monitored, moderately ill patients were sent to community hospitals, and severely or critically ill patients were hospitalized at tertiary hospitals equipped to provide intensive care. It was this bed assignment protocol that helped the health officials to deploy the resources efficiently to treat the patients. In the case of bed shortage for severe or critically ill patients, the Transport Support Emergency Management Office would ensure proper transfer of that patient to a different region/hospital with beds.

Extensive testing and contact tracing were the key ingredients in South Korea’s success.

There were still only four confirmed Covid-19 cases in South Korea on January 27, 2020, when government health officials gathered representatives from more than 20 medical companies in a conference room in Seoul’s biggest train station.

The message was simple: We need tests for this dangerous new virus, as soon as humanly possible, and we will approve yours quickly if it works.

After the MERS scare, the government budget for infectious diseases nearly tripled in five years, spurring a boom in the biotech sector. Some of that new funding was spent on research and development for testing kits.

A week after the train station meeting, on February 4, South Korea approved its first Covid-19 test. The same day, in the United States, the Food and Drug Administration okayed a testing kit designed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The US test would prove unreliable, setting efforts back by weeks. South Korea’s was swiftly validated at more than 100 laboratories. Companies were soon shipping thousands of test kits to labs and hospitals across the country.

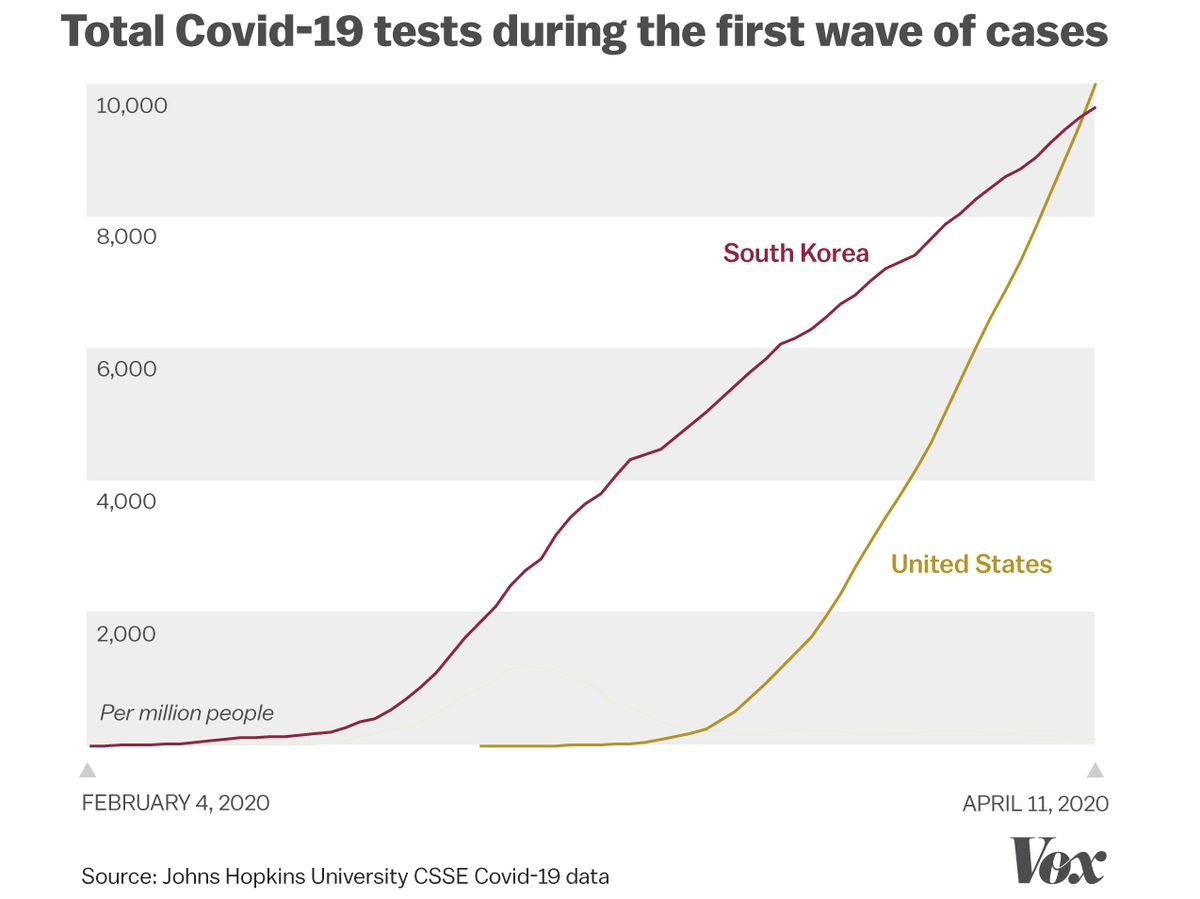

By March 1, South Korea was performing more than 10,000 tests every day. The US couldn’t even manage 100. When adjusting for population, it wouldn’t be until mid-April — when South Korea’s outbreak was under control — that the US would finally overtake Korea in total tests performed.

Germany- Contained the outbreak but political bickering spoiled the party

In Germany, a unified public health response and communication helped tame the pandemic but in the past few months due to the fragmented politics and lockdown burnout, the cases started to rise again leading to a fresh set of lockdowns and mobility curbs.

So what happened? Germany’s federalist system — in broad strokes, similar to the US’s division between federal and state governments — allowed discord among the country’s leaders to have a major impact on the country’s response, slowing down major decisions. Politics played a growing role as well: In 2018, well before the pandemic, Chancellor Angela Merkel announced she would retire in 2021; the political jostling to replace her featured politicians trying to draw contrasts, often with a less cautious approach to Covid-19 than Merkel’s.

All of this turned a nationwide response that was once marked by unity into one that was fragmented, dividing both the public and its leaders.

“It was very much complacency,” Ilona Kickbusch, a political scientist focused on global health at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva, Switzerland, told me. “There was a feeling that we’ll get through this relatively quickly. Many, many countries made that mistake — they thought this pandemic response would be a question of three to six months, but it’s turning out to be between 18 months and two to three years.”

Germany’s experience during the coronavirus pandemic shows how a country can unite behind a single public health message and mission. But it also shows how fragile that victory can be — and how quickly an initial success can collapse once something goes wrong.

“Es ist ernst” (Take it seriously)

These were the words used by German chancellor Angela Merkel in the initial weeks of March last year to urge Germans to take this pandemic seriously. She further added, “Since German unification—no, since the Second World War—no challenge to our nation has ever demanded such a degree of common and united action.”

Merkel knew what she was doing. A scientist herself, with a doctorate in quantum chemistry, she explained the need for open communication on scientific and public health issues: “This is part of an open democracy: that we make political decisions transparent, and explain them, that we establish and communicate our actions as well as possible, so that it becomes relatable.”

She would continue to deliver these direct messages, breaking down what was going on and why Germany needed to take action. In another moment that went viral worldwide, Merkel explained the epidemiological concept of a pathogen’s reproductive number, or its R0, used by scientists to measure a virus’s potential spread. She warned that letting the virus spread at even a 10 or 20 percent higher rate could doom the country’s health care system months earlier than would otherwise be the case.

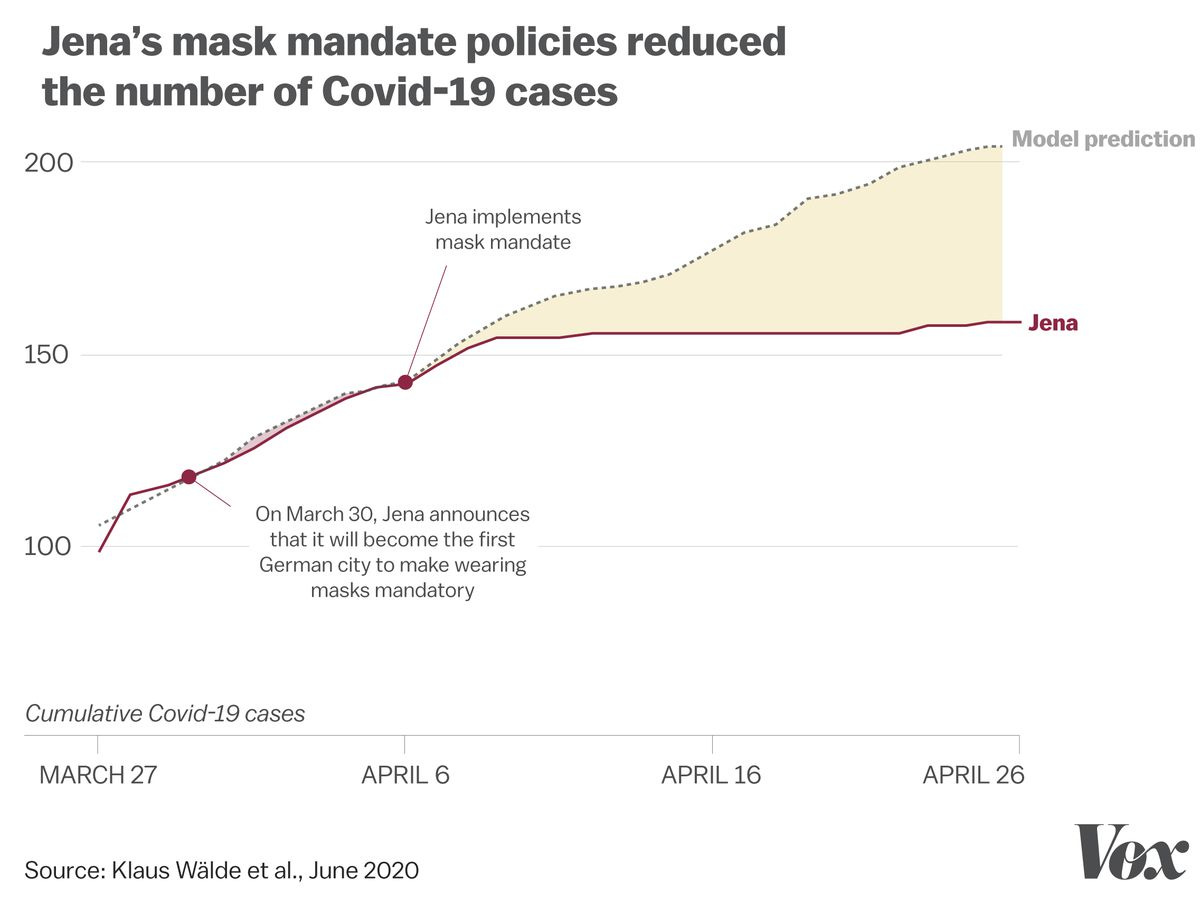

The biggest success story after this address came from a small city called Jena, situated in the southern part of former East Germany. In Jena, the mayor Thomas Nitzsche made mask wearing mandatory in public places.

Nitzsche knew the key to avoiding both these problems would likely come down to how the city’s leaders told the public about the policy. The government would need to transparently communicate the benefits of masks while acknowledging the downsides: Yes, they can be uncomfortable, but masks could flatten the curve, save your family and neighbors, and get life back to normal quicker. And to avoid a run on surgical masks, the local government would emphasize the value of cloth coverings, and encourage people to make masks not just for themselves but for others, too.

“This took a lot of arguing and a lot of information campaigning,” Nitzsche said. “It’s very important to do this together with the people and not on the people. They need to understand. They need to accept. They need to intrinsically want to participate. Then it can work.”

This seemed to have worked.

When the numbers came in April last year the gap between the number of cases that Jena had after the mask mandate and the probable numbers had their been no mask mandate was around 23%.

By the end of April last year all 16 states of Germany made wearing masks mandatory.

However, situation started to change in September around the Oktoberfest when people started coming out without masks and Covid precautions. Some of the leaders from Merkel’s party were not in favour for lockdown since they were backed by anti-lockdown groups.

By the end of October, the scenario Merkel warned about early in the pandemic when she explained exponential spread to a worldwide audience, came true: Daily new Covid-19 cases in Germany multiplied by seven times in the span of the month.

The success of the past few months had built complacency, and the federal system that allowed Jena to experiment with masks now suffocated further progress. The country’s 16 state governments and Merkel’s federal government couldn’t come to an agreement until it was too late, after they saw the results of exponential spread firsthand.

Even then, the country’s governments by November only agreed to what they called a “lockdown lite,” which closed bars, restaurants, and several other indoor spaces. Cases remained stubbornly high throughout November — more than triple the spring peak of Covid-19. It wasn’t until late November that Merkel finally got the 16 state governments to sign on to a stricter lockdown.

One of the reasons for this political fragmentation is the political vacuum created after Merkel’s retirement announcement. There are several aspirants of the post now.

In Germany, the current political era is sometimes referred to as “Merkeldammerung” — the twilight of Merkel. After more than a decade and a half as chancellor, and nearly two decades as leader of the center-right Christian Democratic Union of Germany, she said in her retirement announcement that it was time for the country and her party “to start a new chapter.” Elections in September 2021 will decide the country’s new leader.

Merkel’s long grip on power had made her a defining force in German politics. But all of a sudden, the country found itself on the brink of a power vacuum. Politicians both in and out of Merkel’s party had a chance to vie for the country’s top political position. And many criticized her policies, in part to contrast themselves and bolster their own political fortunes.

All of that became apparent during the week of Ash Wednesday in February, which is traditionally used by German politicians to preview their electoral messaging for the year ahead and criticize their opponents. This year, the hot topic was the country’s continuing months-long lockdown.

Armin Laschet, who had been recently elected to head Merkel’s Christian Democrat party, criticized the lockdown — describing Merkel’s push for communal restrictions as the government treating voters like “underaged children.”

Merkel have to give in to the pressure against strict lockdowns.

In the lead-up to Easter on April 4, Merkel and the governors had agreed to tight restrictions — discouraging domestic travel, closing down more businesses, and prohibiting larger gatherings, including in churches, from April 1 to 5.

The backlash was fierce. Churches demanded the ability to celebrate one of their holiest days. Businesses claimed that a stricter lockdown during a typically busy season would bring financial ruin. State leaders started to buckle under the opposition, calling for a redo on the agreement.

Under all this pressure, Merkel revoked the plan roughly 36 hours after it was announced. “This mistake is mine alone,” she said. “The whole process has caused additional uncertainty, for which I ask all citizens to forgive me.” Merkel added, “There were good reasons for it, but it could not be implemented well enough in this short time.”

One year before, Merkel had been the voice of Germany on Covid-19, with news of her speeches getting families to gather around the TV to listen to what she had to say. The public and politicians followed her lead, anxious to take the cautious approach that she advocated for against the coronavirus. That unity let the country crush Covid-19 during the early days of the pandemic, with headlines praising “A German Exception” and much of Germany, from restaurants to movie theaters, reopening and bustling in the summer.

In the spring of 2021, Merkel was forced to apologize for her caution. Now she hopes to adjust her plan to prevent another potential surge — perhaps by seizing powers originally held by the states. Meanwhile, daily new Covid-19 cases in Germany remain around 50 times higher than they were for much of last summer.

Does this remind you of the mass religious gatherings in India in April?

Vietnam- Strict travel restrictions

Vietnam imposed very strict travel restrictions across the country. There were checkpoints at all major highways connecting important cities. At these checkpoints the travelers were supposed to enter their health and travel details. If they were from areas having high number of Covid cases then they were turned away.

Vietnam literally built a ‘wall’ to control Covid cases.

Early last year, when the US and European countries still focused on keeping out travelers from places with known Covid-19 cases, Vietnam closed its borders to the world.

It was the culmination of months of escalating travel restrictions. On January 3, the same day China reported a mysterious cluster of viral pneumonia cases to the WHO, Vietnam’s Ministry of Health issued a directive to increase disease control measures on the border with China. By the end of January, Vietnam’s then-Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc banned all flights to and from Wuhan and other areas where the virus was spreading in China and shut off every transport link between the two countries, making it the first place in Southeast Asia to close out Chinese travelers.

By mid-March, Vietnam suspended visas for all foreigners and then stopped all commercial flights. Only diplomats, citizens, and other officials could get in or out on repatriation flights, and they needed authorization from the government to enter.

Limited air travel has now resumed with other low-risk neighbors — such as South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan — but only for Vietnamese people and foreign businesspeople and experts. And while Vietnamese nationals can cross land borders from Laos or Cambodia, everybody who does get into the country — by air, land, or sea — has to submit to PCR tests and wait out a mandatory 14- to 21-day quarantine period under state supervision in a military-run facility or designated hotel.

So where Western countries introduced travel restrictions late, targeted their measures at countries with confirmed Covid-19 cases (or variants now), made quarantine optional or didn’t enforce it, and allowed loopholes (like excluding certain groups from travel restrictions, or letting people arriving over land avoid quarantine), Vietnam walled itself in.While Western countries continue to roll measures back whenever case counts come down, Vietnam has kept its wall up — even during periods when the country recorded zero new coronavirus cases.

Vietnam also did a very rigorous contact tracing for the cases that were tested positive.

Contact tracing became so widespread that the population now speaks the language of epidemiologists: It’s not unusual to hear Vietnamese people refer to the “F1” through “F5” system — how contact tracers denote a person’s proximity to an “F0,” or index case. (And, yes, where Western governments largely abandoned contact tracing or didn’t even seriously attempt it, Vietnam continues to ferret out potential cases by testing all F1s — a patient zero’s immediate contacts — and quarantining them in a state facility, while also asking F2s to quarantine at home.)

Vietnam’s success also lies in her early detection and containment strategy. Since its economic reforms in the 1980s, Vietnam has invested a lot in public health system.

These investments have paid off with rapidly improving health indicators. Between 1990 and 2015, life expectancy rose from 71 years to 75 years4, the infant mortality rate fell from 36.9 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1990 to 16.5 deaths in 2018,5 and the maternal mortality ratio plummeted from 139 deaths per 100,000 live births to 54 deaths.6 The 2018 immunization rate for measles in children ages 12 to 23 months is over 97 percent.

Vietnam has a history of successfully managing pandemics: it was the first country recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) to be SARS-free in 2003, and many interventions Vietnam pioneered during the SARS epidemic are being used to respond to COVID-19. Similarly, its experience with epidemic preparedness and response measures may have led to greater willingness among people in the country to comply with a central public health response.

-Our World in Data

Vietnam ramped up its testing capacity very quickly. When the Ministry of Science and Technology, in January, met few virologists and asked them to start developing diagnostic test kits, the publicly funded institutions developed 4 diagnostic tests. The private companies then took the manufacturing of these kits on a different level. Subsequently testing sites were increased. The health officials focussed on testing people from the clusters where the number of positive cases was more.

Vietnam used a very different strategy for contact tracing. The contact tracing was based on the degrees of contact from the infected person (F0). The person who would have come in contact with F0 would be traced (F1) and then F2, F3 and so on and so forth.

Based on the epidemiological evidence from the clusters, Vietnam imposed targeted lockdown. Hence South Korea and Vietnam successfully flattened the curve because the outbreak was detected very early, it was monitored well, more number of tests were performed, effective contact tracing helped contain the virus and meaningful partnerships with the scientific community and the private sector were forged.

Further reading:

1) How Senegal stretched its health care system to stop Covid-19

2) How the UK found the first effective Covid-19 treatment — and saved a million lives