Dispatch #56: ‘Prashn nahi uthta’- Unpacking democratic accountability

In this dispatch we will look at a practical guide to enforce democratic accountability

In a reply to the question on deaths due to shortage of oxygen in Uttar Pradesh, the health minister of the state said that there were no such deaths. The question asked in the Legislative Council was, ‘Can the health minister please tell whether there were deaths in Uttar Pradesh, due to oxygen shortage during the second wave?’ The minister replied, ‘There were no deaths reported due to oxygen shortage’.

This denial does not stand under scrutiny if one looks at the ground reports and the data about the Covid deaths in Uttar Pradesh. While the Covid related deaths were heavily under-reported in UP, according to this analysis by Article 14, here is a whole list of people who lost their lives in different cities of UP during the second wave. These numbers were compiled by a group of data experts from the death reports in the newspapers and social media.

If there was no oxygen shortage in UP then why did the Oxygen Express arrive in UP in April, all the way from Bokaro? Why were oxygen plants inaugurated by the UP CM in October 2021, if the state had sufficient oxygen in the summer of 2021?

These questions need to be answered as our rivers turned into dumping ground for the dead. The denial of deaths in the UP assembly is a textbook case of undermining democratic accountability by a democratically elected government. Democratic accountability, public services and governance has been an underlying theme of several of my older dispatches. In this dispatch I would like to present a practical guide of democratic accountability in public service delivery.

But before that we need to brush up our basics.

The classic definition of accountability rests on the principal-agent relationship. ‘A is accountable to B if A has to explain and justify his/her actions to B, and B is able to sanction A in case of misconduct’. What makes this accountability ‘democratic’ is the scenario when B is the electorate and the voters have elected A as their representative to fulfill their wishes.

Political scientist Johan P Olsen, in his book titled ‘Democratic accountability, political order and change’, has this to say about democratic accountability:

Democratic accountability implies governance based on feedback, learning from experience, and the informed consent of the governed. Citizens are neither the initial authors of laws and budgets nor the designers of the political order under which they live. But they are not powerless. Although most decisions are made by elected representatives, appointed officials, and other power holders, rulers still have an obligation to be appropriately accountable to the ruled. In well-functioning democracies it is difficult for decision makers not to respond to calls for accounts without losing legitimacy. Power without accountability is illegitimate, and unaccountable government implies a democratic deficit and an illegitimate political order. Those acting on behalf of the population must describe, explain, and justify their actions and face possible consequences. Power holders are expected to act in anticipation of having to account for their actions, and expecting to be held responsible makes a difference in both behavior and the way behavior is explained and justified.

-Johan Olsen

Olsen further explains:

A viable political order needs legitimacy and support from its citizens. The essence of morality lies in the right of each citizen to demand an account from others of what they have done and to discuss what are good reasons for accepting behavior and accounts as satisfactory. Political actions, institutions, and outcomes require explanation and justification, and accountability demands are linked to what is seen as legitimate in a political culture, that is, what citizens in a specific setting and time period see as an appropriate arrangement of governmental institutions, and what behavior, outcomes, explanations, and justifications are viewed as acceptable. Specifically, democratic legitimacy is based on the voluntary consent of the governed, and in that context legitimacy can also refer to what normative democratic theories define as good arguments for justifying a belief in the rightfulness of a political order, ideas often linked to assumptions regarding what citizens would accept if fully informed.

-Johan Olsen

This brings us to the question of whether there will be a voter backlash in India because of the massive mis-management of the Covid situation during the second wave. In June, Ashutosh Varshney and Amit Ahuja argued that the suffering due to pandemic is not due to ‘vidhi ka vidhan’ but ‘sarkar ka vidhan’ which relied more on denial and obfuscation.

Even religiously rooted human beings don’t consider all kinds of grief to be equal. Some are more easily linked to fate, others are inflicted by those in power — by their policies, or by their sheer absence in times of need. Whether or not a democratic government can bring joy and happiness, one of its key responsibilities is to prevent mass suffering, or alleviate its severity. At a time of deep collective agony and pain, a democratic government’s virtual disappearance — or its appearance only to punish citizens, journalists and health professionals doing their job — borders on brutish incomprehensibility.

-Varshney and Ahuja

An executive can be held accountable by two means. Either by the Parliament or directly by the citizens. In the past few years, the Indian Parliament has not been able to put the executive in check because of obvious reasons. Accountability by the citizens or democratic accountability has been undermined by the executive by deflecting the attention of the electorates from important national issues and razor sharp focus on an individual. One assumption in democratic accountability is that being a democracy, accountability mechanisms will make sure that service providers (government and public officials) deliver quality services. Holding the government accountable to public services is the hallmark of democratic accountability. In Indian context, since the BJP has emerged as a hegemonic political force and the opposition parties have become ineffective and non-consequential, the ruling dispensation faces no political competition. In the absence of such competition there is less incentive to come up with good policies because the incumbent’s risk of losing office is quite low.

Let’s look at the democratic accountability, in the context of the 2014 and 2019 elections.

The conventional wisdom would tell us that the voters punish the incumbent political party if it has performed poorly on the economic front. The 2019 general election was an aberration to this wisdom. The incumbent BJP was up against the wall when the challenger, the Congress, was trying to make slow economic growth, rural crisis and unemployment as electoral issues. The BJP came back to power with a stronger mandate and an increase in the vote share. The economy seemed to be a non-issue for the voters.

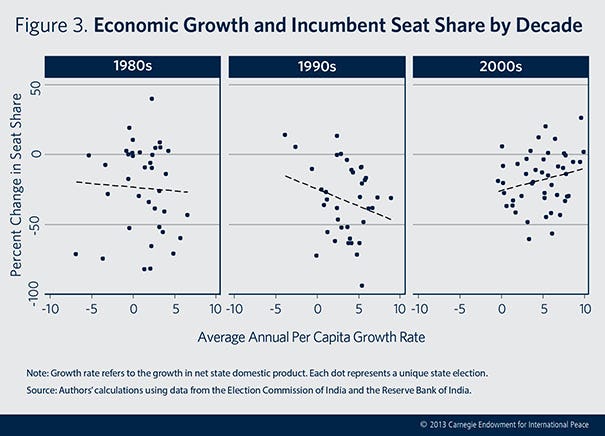

In their 2015 paper titled ‘Does good economics make for good politics?’ Milan Vaishnav and Reedy Swanson examined the correlation between economic growth and electoral returns of the incumbent party in various state elections. Their analysis shows that in the 1980s and 1990s, there was either a negative correlation or no correlation between the economic growth and the percentage seat and vote share of the incumbent political party. But in the 2000s there was a positive correlation between economic growth and the electoral return of the incumbent party. This essentially means that in the 2000s the voters were kicking out the incumbent government if they were not able to deliver on the economic front.

The authors argue that there could be three reasons behind the positive correlation between economic growth and the shift in voters’ behaviour in the 2000s:

a) Except in the last years of UPA 2, India and the states witnessed high levels of economic growth. This could have increased the voters’ aspirations, who rewarded the party that made policies that positively impacted the economic fortunes of the voters. In addition to that, some state governments actually did a good job in making sure that every section of the society could reap the dividends of rapid economic growth.

b) The political competition has increased since the late 1980s and 90s with the rise of the regional parties and political satraps. The voters have an option to ‘exit’ from one political party and support the other because they see their economic fortunes improving in the opposite camp. This left the incumbent political party with no other choice but to deliver on the economic front.

c) The voters also realised that it’s the state governments that could lead the efforts on the economic front. Hence they turned out in large numbers during the state elections to make the state governments accountable for the economic growth of the state and their individual economic fortunes.

This trend continued till the 2014 general assembly elections when the voters were angry with the UPA 2 because of corruption and sluggish economic growth. They were looking for a leader who is strong, decisive and who can take decisions that would take India on to a growth trajectory. However, the 2019 general elections was an exception. Conventional wisdom says that the voters would turn out in large numbers on the voting day to kick out the incumbent government since it failed to deliver on the economic front. Voters did turn out in large numbers in 2019, but only to get the incumbent government back in power even after delivering poorly on the economic front and a 40-year high unemployment rate.

Political scientist Neelanjan Sircar calls this the politics of ‘vishwas’. There was a reason why the BJP made ‘sabka saath, sabka vikas, aur ab sabka vishwas’ their slogan as they fought the 2019 elections. By invoking the term ‘vishwas’, the BJP wanted the voters to trust PM Modi even though things were not looking good. The politics of ‘vishwas’ is personality-driven, people always trust the charismatic leader to make the right decisions and centralisation of power is one of its basic tenets. The politics of ‘vishwas’ is a complete antithesis to democratic accountability. In the democratic accountability polity, voters have a certain set of ideas around their economic well-being and they evaluate the incumbent political party on that basis. In the politics of ‘vishwas’, the leader can change the narratives very easily.

The differences between the politics of vikaas and vishwas structure political and electoral behavior in important ways. In traditional models of democratic accountability, i.e. the politics of vikaas, there is little room for the role of the political mobilization and little discussion of what makes voters turn out to the polls. In the politics of vikaas, the voter looks at the choices available to her and selects the candidate or party most likely to deliver economically or closest to her in terms of ideology. These models require that a voter can identify a stable set of issues consistent with their own preferences and have sufficient information on the preferences and attitudes of political actors. In the politics of vishwas, the reverence to a particular politician is explicitly a function of how well the individual politician is able to connect to the voter (or, perhaps, demonize the opponent) – chiefly through media or the strength of party organization.

-Neelanjan Sircar

The politics of ‘vishwas’ rests on the huge machinery of electoral mobilisation. The BJP has created a formidable election machine over the years because of its cadre and also because it dominates the electoral funding landscape. Neelanjan argues that the electoral mobilisation, increase in voter turnout and politics of ‘vikas’ and ‘vishwas’ are closely related to each other. He has analysed the voter turnout data and the probability of the BJP winning that election.

In the 1999 and 2004 elections, when the BJP was the incumbent, the probability of winning would drop with increase in voter turnout. In 1999, it won the elections but in 2004 it lost against the Congress and her allies. In 2014, there was anti-incumbency against the UPA and the voters came out to vote in large numbers to kick the UPA 2 out. This is the politics of ‘vikas’.

In the 2019 elections, the voter turnout increased and they voted the BJP back in power with a thumping majority. This is quite contrary to the democratic accountability model logic. At a time when the country is growing through its worst unemployment and rural crisis, the voters should have been harsh on the BJP. This is the politics of ‘vishwas’. The voters trusted the infallible leader who would put their interest before anything else.

The democratic accountability model gets undermined when the political parties are deinstitutionalized, the linkages between the voters and the party ideologies are weak but the linkages between the voters and individuals are personalistic, argue Scott Mainwaring and Mariano Torcal. An example of this personalistic linkages could be the BJP campaign where it urged the voters to vote since each vote to the BJP will be a vote to PM Modi. So it does not matter who your representative is as long as your vote is for the leader.

Another important feature of this brand of politics is that while the credit for the achievement goes to the leader, the responsibility for any failure doesn’t. The leader is capable of deflecting blame and criticism. This has been referred to as the ‘teflon coating’ around the leader. A similar teflon coating has been created around PM Modi. In political marketing terms, there are two types of politicians across the political spectrum- teflon personalities to which nothing sticks and velcro personalities to which everything sticks.

While these abstract ideas and concepts are great to understand what’s happening in India at a macro level. But do we have a framework that can subject public service delivery and economic performance to democratic accountability?

The researchers at the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA) have attempted to create an actionable democratic accountability framework. The framework enables the citizens to subject public service delivery to democratic accountability and design areas of action in case of improvement. The framework also helps in distinguishing cases in which the service provider was not able to deliver the service and cases in which it is just not possible to deliver some services.

As mentioned above, there is a democratic accountability in service delivery when citizens hold the public officials or the government accountable for the quality of public services and provide feedback. The IDEA scholars have given them the following names:

Duty bearers- Government and public officials

Claim holders- Citizens

The next step to understand the framework is to ‘determine whether mechanisms of accountability between duty bearers and claim holders are at work throughout the entire policy process that leads to the provision of public services’ and to devise actions to improve the accountability mechanisms.

Any public policy usually have these three broad phases:

Agenda setting: This is the phase in which an issue or problem becomes a priority for citizens and public officials.

Policymaking: In this phase several policy alternatives are enlisted and trade-offs are done to zero in on one or two policy solutions.

Policy implementation: This is the phase where the policy is executed by the public officials.

Democratic accountability rests upon three conceptual pillars that help claim holders to hold duty bearers accountable. These principles are:

Answerability: This is related to how effectively duty bearers explain and justify their decisions to claim holders.

Responsiveness: This is related to how often duty bearers take the opinions or feedback of the claim holders while delivering public services.

Enforceability: This is related to the consequences that the duty bearers would face had they fail in delivering quality services to the claim holders.

Now if you consolidate all the concepts discussed above into a framework, you will get something like this:

It essentially indicates how the duty bearers are answerable and responsive to the claim holder during all three phases of policy making- agenda setting, policy making and implementation. It also indicates the degree up to which the claim holder can impose consequences on the duty bearer in the event of the later failing to deliver quality services.

Hence the framework not only helps in identifying the gaps in enforcing accountability on public officials but also helps in identifying the actions that the citizens can take to enforce the accountability.