Dispatch #64: State building-Scope and strength

In this dispatch, we will see how state formation happens.We will also explore two key dimensions of stateness- scope and strength and their impact on economic growth

Commenting on the economic zeitgeist, against which we have been witnessing a massive backlash for over a decade, Pratap Bhanu Mehta in his 2020 incisive essay titled ‘History after Covid-19’ said that that economic order was built on five shaky pillars. These pillars are:

Exit: The elites have always found an opportunity to secede themselves from the already decaying public systems and find refuge in alternate private services provisioning. The exit happened in a classic Hirshmanian way in India, over the past several decades.

Invisibility: The tendency of turning our heads away and ignoring the presence of the poor who have to face the daily indignity of being poor. P Sainath rightly described this phenomenon during the Covid-19 crisis when he said that ‘urban India didn’t care about migrant workers till 26 March, only cares now because it has lost their services’.

Inequality: The chasm in our society can be well defined by the metaphor, used by Mehta in another essay where the haves and have-nots are standing at the two extreme ends of a dark well, knowing that the ends would never meet. The Covid-19 crisis has exacerbated the situation where households have seen a massive decline in their earnings.

Insecurity: Providing security or any type of cushion became a bad word. We were told that providing job security may distort the labour market, providing income insecurity may reduce incentives and providing social security is bad for the economy.

Privatisation: This is related to the first principle of ‘exit’. The decline in the quality of public services resulted in people moving to private provisioning en masse.

These five principles were considered as organising principles of the way our society has been structured. These pillars have a very strong foundation. It was assumed that they couldn’t be shaken.

Covid-19 changed everything. The pandemic forced us to realise that these very foundational ideas were the cause of the greatest humanitarian crisis in India post-partition.

One of the notions that gave massive pushback to the above-mentioned five principled approaches was the return of the state. Mehta argues that there are four aspects of the crisis that substantiated the role of the state in such situations- state capacity matters, the state’s role in macroeconomic management during the crisis, the state’s welfare measures and the fact that the crisis impacted all classes of people and even the middle class would require state support.

If you analyse these four aspects, essentially they define the scope (what are the state functions) and strength (how effective is the state in performing some functions). The objective of this dispatch is to understand the scope and strength of the state. I will heavily borrow concepts and frameworks from Francis Fukuyama’s ‘State building: Governance and world order in the 21st-century’ book.

But first, let’s start with the basics.

In his 1918 lecture titled ‘Politics as a vocation’, German sociologist Max Weber defined the state as an entity that has the ‘monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force’. This monopoly of the legitimate power by the state can be used to protect property rights and provide security or it can also be used to suspend civil liberties and confiscate property.

Fukuyama adds:

The task of modern politics has been to tame the power of the state, to direct its activities toward ends regarded as legitimate by the people it serves, and to regularise the exercise of power under a rule of law.

In the 20th century, the size, strength and scope of the state were not too elaborate. In Great Britain, there were no income support programs or health programs. It took a series of wars and the Great Depression for the minimal liberal state to be replaced by a centralised and active one. This led to two different groups of countries- totalitarian and non-totalitarian. The totalitarian regimes tried to abolish all civil liberties and organised the society to meet the political ends of the supreme leader. The right-wing version ended with the defeat of Nazi Germany and the left-wing version collapsed under its own contradictions with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. The size, strength and scope of the state increased both in totalitarian and non-totalitarian regimes, throughout the 20th century. It was only around the late 1980s when reducing the size of the state became one of the key focal points in policy making in Latin America, Asia, Africa and former communist countries. The international financial institutions (IFIs) such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund offered advice to these countries to reduce the glut due to the ‘big’ state and embrace structural reforms. This was the Washington Consensus.

Fundamentally, there was nothing wrong with the Washington Consensus. The state sectors of the developing countries were the cesspool of inefficiencies, corruption and rent-seeking. Scaling them back was the logical way to let markets work and promote economic growth. The problem was that while the state needed to be cut back in a few areas, it needed to be strengthened in other areas. In the process of cutting back state activity in certain areas, what got deliberately misconstrued, argued Fukuyama was that reducing state activity is also reducing state capacity across the board. This led to the undermining of the state-building process since the state capacity was stunted from critical areas where the state should have been present such as providing education and healthcare. Because of the lack of an institutional framework of the state, economic reforms due to liberalisation failed in some countries. To understand the institutional framework of the state and its ability to do things well, we need to understand different dimensions of stateness and how they impact economic growth.

Dimensions of ‘stateness’: Scope and strength

The scope of state activities refers to different functions and goals of the governments. The strength of the state refers to the ability of the state to plan and execute policies and enforce laws. The latter is also referred to as state or institutional capacity.

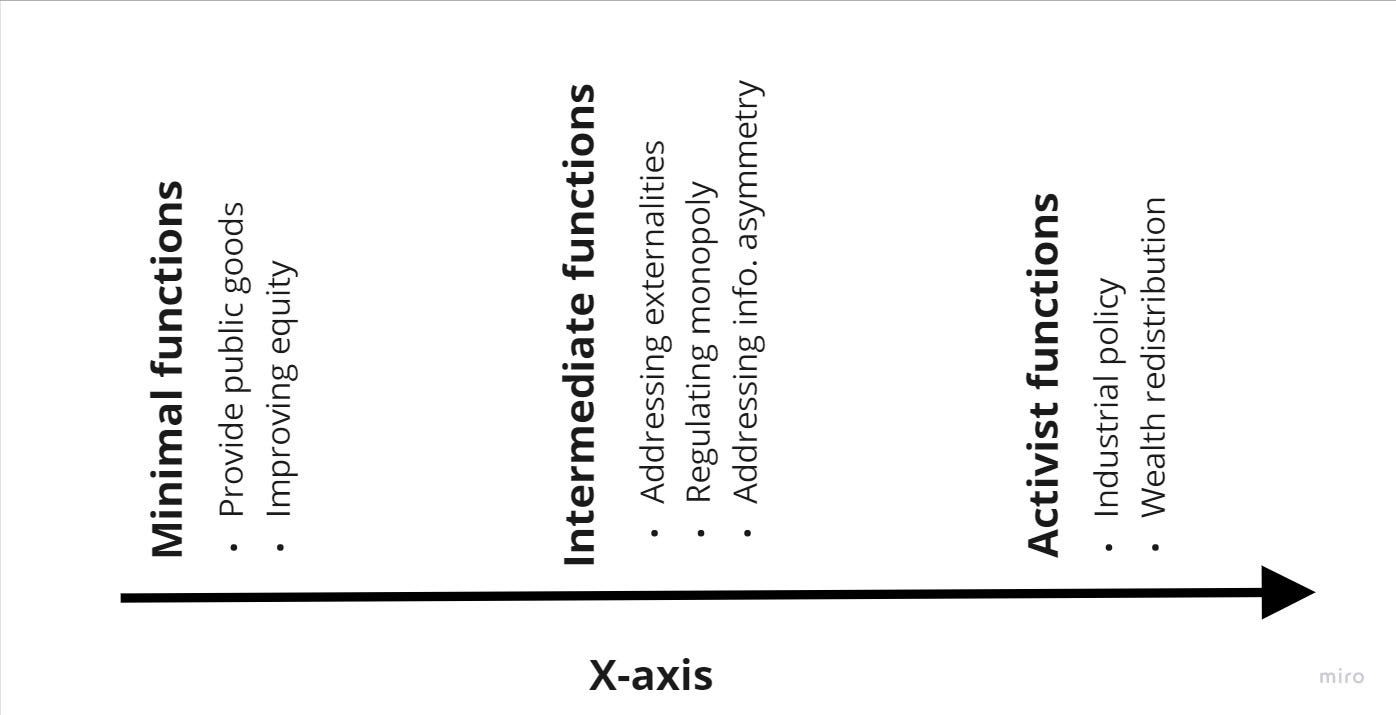

In the World Bank’s 1997 World Development Report, the state functions were divided into three broad categories- minimal, intermediate and activist.

The chart above enlists the functions of the state ranging from ‘activities that will not be undertaken at all without state intervention to activities in which the state plays an activist role in coordinating markets or redistributing assets’.

Countries with low state capacity or low strength should focus on providing basic public goods such as law and order, protecting property rights, macroeconomic management and public health. Beyond these minimal functions, the state has intermediate functions such as addressing externalities, regulating monopoly, addressing information asymmetry and providing social insurance. Finally, the state with strong state capacity can have an activist role in fostering markets and redistribution. East Asian countries fall under the third category where the state promoted markets through industrial and financial policy.

Fukuyama took these functions and placed them along the X-axis. This made placing different countries on the axis as per the functions that they are able to perform. This essentially represents the scope of state functions.

We can have a Y-axis with the strength of state functions or institutional capacity. Strength ‘includes the ability to formulate and carry out policies and enact laws; to administrate efficiently and with a minimum bureaucracy’. There cannot be a commonly accepted measure for the strength of the state institutions. Different state agencies may have different strengths. Therefore, state capacity may vary across state functions. Fukuyama gives a brilliant example to support this point:

A country might have a very effective internal security and yet cannot execute simple tasks like processing visa applications or licensing small businesses.

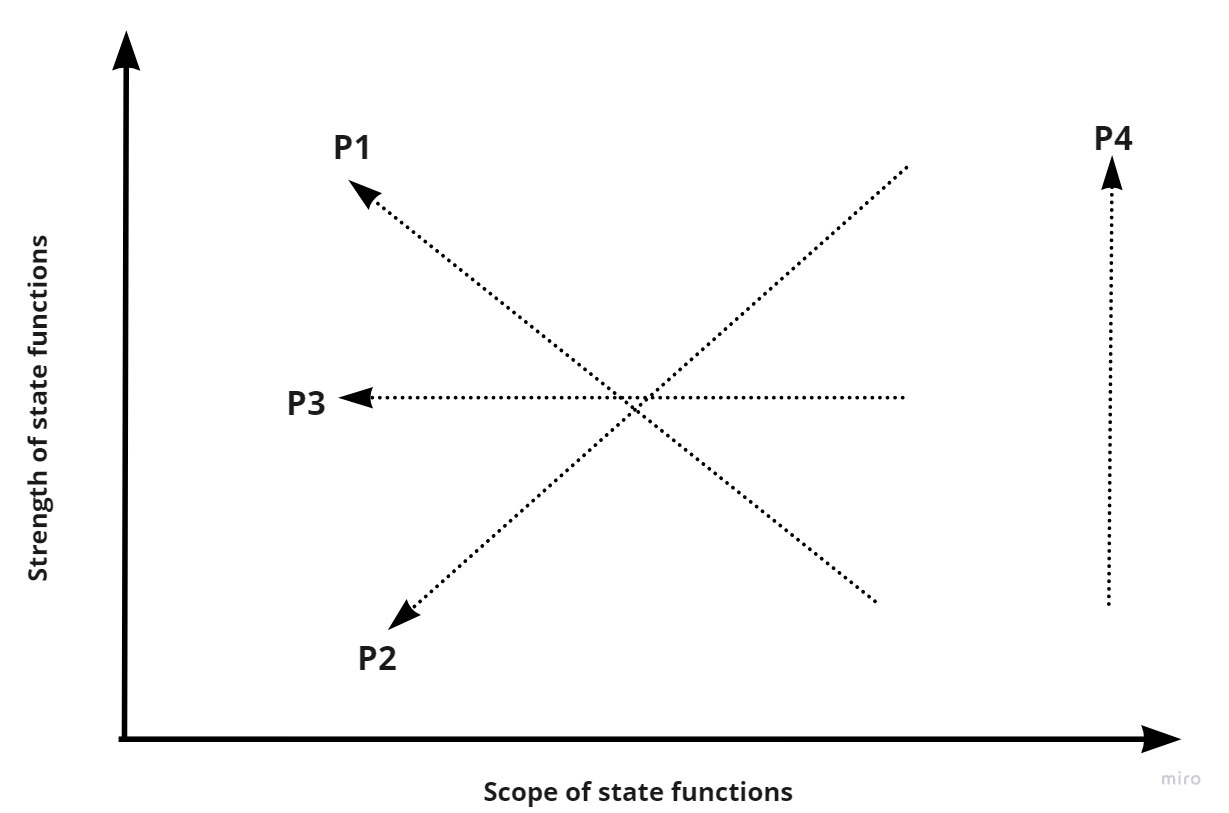

Now, if we combine the two dimensions of stateness, i.e. scope and strength in a 2x2 matrix then we get something like this:

The matrix gives us 4 different quadrants that have different implications for economic growth. From an economist’s standpoint, Q1 is the optimal quadrant for a country wherein the scope of state functions is limited and the strength or institutional capacity of the state to do the limited functions effectively is high.

Fukuyama explains:

Economic growth will cease, of course, if a state moves too far toward the origin of the axis and fails to perform minimal functions like protecting property rights, but the presumption is that growth will fall as states move farther to the right along the X-axis.

Several European countries that do not want to compromise on social justice or do not want to emulate American-style efficiency lie in Q2. The worst quadrant that a country can find itself in is Q4 where the scope of state functions is large and its state capacity to implement activities is low. This is an ‘ineffective' state. Unfortunately, a large number of developed countries lie in this quadrant. Having said that, countries can move within the four quadrants. Their positions are not cast in stone and they vary as and when countries change the scope and strength of state functions.

Scope, strength and economic development

The policy measures under the Washington Consensus, in the early 1990s, recommended that countries remain in Q3 with weak institutional capacity or strength and limited scope of state functions. The assumption was that the ‘markets would be self-organising or that institutions and residual state capabilities would somehow take care of themselves.’ The Washington Consensus made sure that more countries would move leftwards on the X-axis, thus its policy measures included reduced tariffs, privatisation, reduction of subsidies etc. By moving to Q3, the emerging economies not only reduced the state scope they also decreased the state strength.

While the most optimal path would have been P1 where the scope has been reduced and the strength has been increased, many countries follow P2 where both the scope and strength have been reduced. So the countries end up lying in Q3 rather than Q1. Hence, the countries underwent liberalisation in the absence of proper institutions.

Fukuyama adds:

The privatisation of state-owned enterprises is of course an appropriate goal of economic reform, but it requires a substantial degree of institutional capacity to implement properly. Privatisation inevitably creates huge information asymmetry, and it is the job of governments to correct them. Thus while privatisation involves a reduction in the scope of state functions, it requires functioning markets and a high degree of state capacity to implement.

It makes more sense for the countries to have high levels of strength or institutional capacity and low scope of state activities. The success of East Asian economies, argues Fukuyama, is due to the superior quality of state institutions.

Another reason to think about the significance of state strength is the fact that there is a strong positive correlation between per capita GDP and the percentage of tax extracted by the governments. The ability to extract tax is a measure of state strength. Countries with low state strength have a weak institutional capacity for tax compliance and enforcing tax laws.

In the next dispatch, we will look at the importance of institutions and delve deeper into the evidence for ‘patchwork’ state formation in India.