Dispatch #72: Indian middle class and labour market

In this second dispatch on India's middle class we delve into the interconnections between the rise of middle class, economic liberalisation & labour market

From the previous dispatch, you would recall the occupational profile of the middle class in India. The richest top 2 deciles, which Bijapurkar and Wong consider India’s genuine middle class, have a very worrying occupational profile. Only 58% of D10 and 43% of D9 deciles have regular salaried jobs. 26% of D10 households and 42% of D9 households depend on small agricultural and non-agricultural self-employment, making the upward mobility of this income section highly unstable.

Let me begin this dispatch with another set of data presented by Bijapurkar and Wong on the educational demographics of the Indian middle class.

Only 40% of households in the D10 decile and 20% of homes in the D9 decile have technical diplomas, graduate & post-graduate degrees or professional higher education. This education profile of the middle class ‘is not conducive to upward mobility into value-added skilled jobs’.

Without delving into the academic literature on the interconnections of human capital development (such as education) and social upward mobility, I would like to point out some key interlinkages. Human capital development such as educational advancement leads to the development of critical cognitive and non-cognitive skills which in turn impacts labour market outcomes, which later impacts the overall social upward mobility. In his book ‘India is Broken’, economist Ashoka Mody has also argued that historically low investments in education by India led to less worker productivity and hence less upward mobility. This is how he explains India’s low productivity of workers:

The problem through these critical years was the low productivity of Indian workers, which largely offset the advantage of their low wages. A startling calculation by the economic historian Gregory Clark showed that if Indian workers in 1910 were magically made as productive as those in New England (United States), their wages could rise fivefold, from $0.78 a week to $3.93 a week, while maintaining high profitability on scarce Indian capital. The implication was sobering: Indians were poor because industrial workers- even in the country’s most internationally successful industry- had such low productivity.

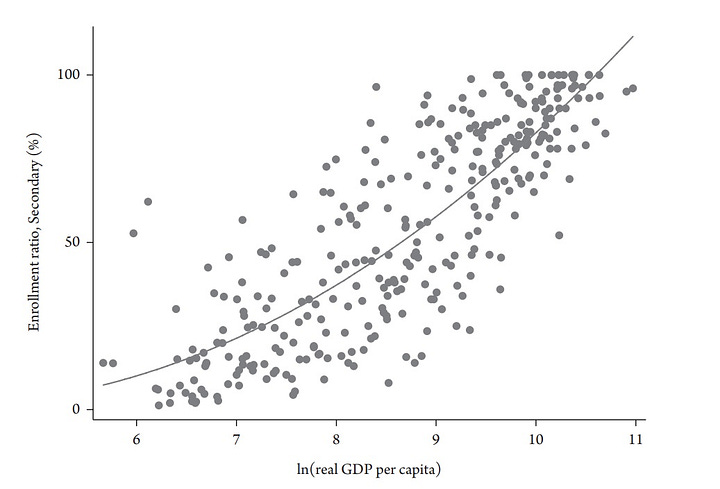

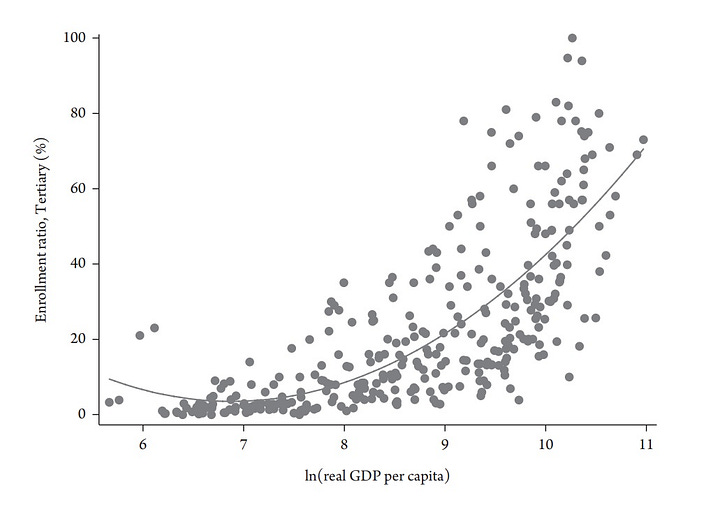

Mody further argued that the difference in education levels between countries explains the differences in productivity. Robert Barro and Jong-Wha Lee in their famous book ‘Education Matters: Global Schooling Gains from the 19th to the 21st Century’ have used extensive data to show a strong positive relationship between global enrollment rates in secondary and tertiary education and income level.

This poor human capital development has a bearing on India’s labour market which further constricts the growth of the Indian middle class. Bijapurkar and Wong in their second article on middle class took a deep dive into the factors that are leading to a stunted middle class in India. They argue that it is ‘both the cause and consequence of the widespread informal sector that is commonly estimated to account for 90% of employment, but generating only a third value added in the economy’. This informalisation of the economy and labour market pushes the prospective middle class into a low productivity trap. The informal workers work in conditions of instability, both in terms of their employment and incomes. Most of them work as temporary or contract workers. The informal sector, with its precarity, disincentivises ‘the employer from investing in productivity-enhancing tools and training workers to use them since pay-off time horizon is longer term than the workers’ tenure’. In a nutshell, the informal economy of India pulls down worker productivity, resulting in low incomes for a majority of the working population (households mostly lying in D5 to D1 income deciles). Now connect this with the three key factors for middle-class expansion- income stability, resilience and ability to grow income through value-added work- and you have a comprehensive picture of what’s holding back the Indian middle class.

By now you would have guessed the sector that has the potential to increase productivity and labour force participation in India. It’s manufacturing. Economist Dani Rodrick has compared manufacturing with the elevator that has the potential to lift a country’s productivity from the basement to the penthouse.

Bijapurkar and Wong argue:

India’s stunted middle class is also the flip side of its stunted manufacturing sector, a significant proportion of which is fragmented and carried out mostly by small and micro enterprises, which do not possess the competitive efficiency to grow and create formal jobs.

The initial dispatches of this newsletter have covered India’s flawed economic pathway extensively:

Dispatch #4: India's 'precocious' development pathway-Part 1

Dispatch #5: India's 'precocious' development pathway-Part 2

Dispatch #6: India's 'precocious' development pathway-Part 3

The authors suggest that:

In order to rapidly expand India’s genuine middle class with all its manifold benefits, there appears to be no shortcut to creating a large-scale manufacturing sector that can drive formal employment.

Let’s stay on this theme and see how India’s structural transformation has contributed to this situation.

Andres Eggimann and Michael Jan Kendzia, in their paper titled ‘Rise of the Indian middle class and its impact on the labour market’, have shown how the sectoral change of the economy has impacted the labour force participation rate. The figure below shows the changes in the sectoral contribution to the GDP in India from 1991 (the year when economic reforms happened) to 2019. One can clearly see the structural transformation which India has undergone. The share of agriculture in the GDP declined from 27.3% to 16.02% between 1991 and 2019. The share of services has increased from 37.79% to 49.39%, whereas the share of the industry has almost stagnated.

This change in sectoral contribution to India’s GDP resulted in a massive transformation in the labour force distribution across the sectors. While the share of employment in agriculture has reduced from 63.3% to 42.6%, the share of employment in industry and services has not been very significant. In industry, the share of employment increased from 15.2% to 25.1% and in services, the share of employment increased from 21.5% to 32.3% between 1991 and 2019. So millions of people moved out of agriculture to the non-agriculture sector only to find out that either there weren’t many jobs or even if there were, the productivity levels were very low.

In his 2018 article, Pramit Bhattacharya analysed the top ten job-generating sectors in post-liberalisation India. The construction sector has emerged as the largest job generator for those who were moving out of agriculture. But look at the productivity level of this sector. It is still very low compared to other job-generating sectors. Productivity level is critical since it determines the income levels of the workers. High productivity sectors, according to this analysis, are the business and financial services which require high-quality skills and are not mass job generators. The share of the total workforce in 2015-16 was 2.18% for business services and 1.11% for financial services.

Pramit adds:

Since 1990-91, the construction sector added almost as many new non-farm jobs as the next four top job-generating sectors—trade, miscellaneous services, transport and storage, and education—put together. While the construction boom in the country has helped people seeking an exit from farm jobs to find an alternative, it has not helped them move to a very productive job. As the accompanying table shows, construction has among the lowest productivity among the top job-generating sectors. To be sure, the sector’s productivity level is about 58% higher than in the farm sector (agriculture, hunting, forestry, and fishing). The construction sector’s productivity is also higher than that in the gems and jewellery and hotels and restaurants sectors. Nonetheless, the construction sector stands out because it is the only sector among the major employers in the country which has witnessed a decline in productivity over the past few years, even as it has added more and more workers to its ranks. One reason for this could be the low level of labour quality (measured in terms of education and experience of workers). Thus, while the farm sector has indeed shrunk, the transformation of the economy has been limited by the paucity of productive jobs and the lack of skilled workers.

The expansion of the services sector was not only the result of domestic liberalization but also of the increase in FDI inflows in the post-liberalisation period.

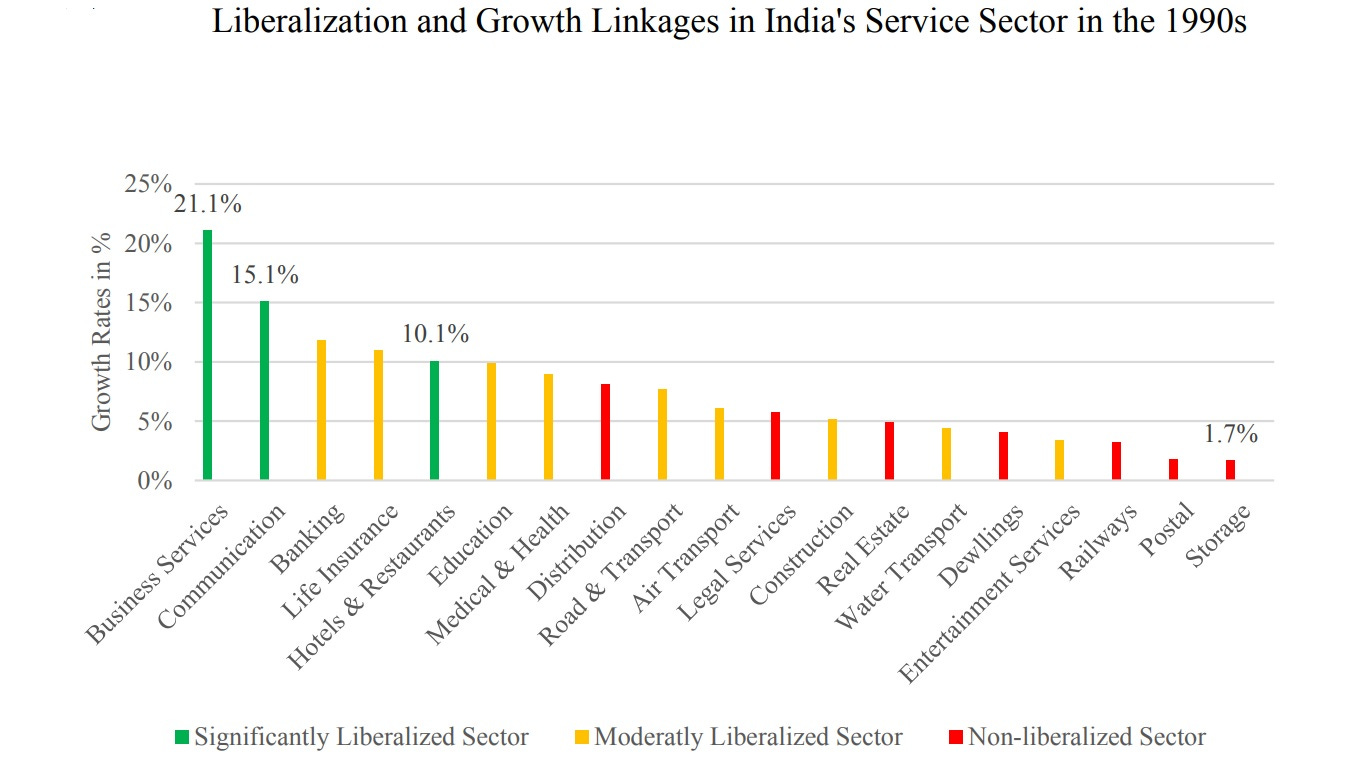

This combination of liberalisation and FDI surge resulted in the growth and employment generation in a few sub-sectors in the service sector, in the 1990s. Eggiman and Kendzia have used the World Bank data to show liberalisation and respective growth rates of a few sub-sectors.

They add:

Most notably both the business services sector and the communication sector experienced the highest growth rates with 21.1 and 15.1 percent. The internationalization of whitecollar employment mainly explains the growth of the business service sector in India (Fernandes, 2006). Many multinational companies, mainly from the US and the UK, began to relocate certain operations, such as customer service, to the suburban areas in India. As a result, many IT parks emerged in several tier cities like Bangalore, Delhi, Chennai, Hyderabad, Kolkata, and Pune, whereas Mumbai became a financial center.

Unfortunately, only a few million well-educated and highly skilled people were able to take advantage of the economic boom, FDI in-flows and growth of the service sector since the 1990s. This happened because they were well-positioned to gain an advantage owing to high education levels, compared to millions of others who came out of agriculture but due to lack of education and skills, they were stuck in low-productivity jobs. Ashoka Mody, in his book, also shows how East Asian economies increased their worker’s productivity levels by investing in early education and making sure that more men and women are finishing school and college.

To probe further into India’s middle class and labour market, Eggimann and Kendzia explain the dualism in the Indian economy in terms of employment and enterprises. Dualism essentially means segmentation of the labour market and enterprises. In India, dualism occurs in two ways:

Labour market

Formal: Regular & salaried workers, covered by social security

Informal: Self-employed & casual workers, not covered by social security

Enterprises

Organised: Non-agriculture businesses employing >10 workers & registered

Unorganised: Non-agriculture businesses employing <10 workers & unregistered

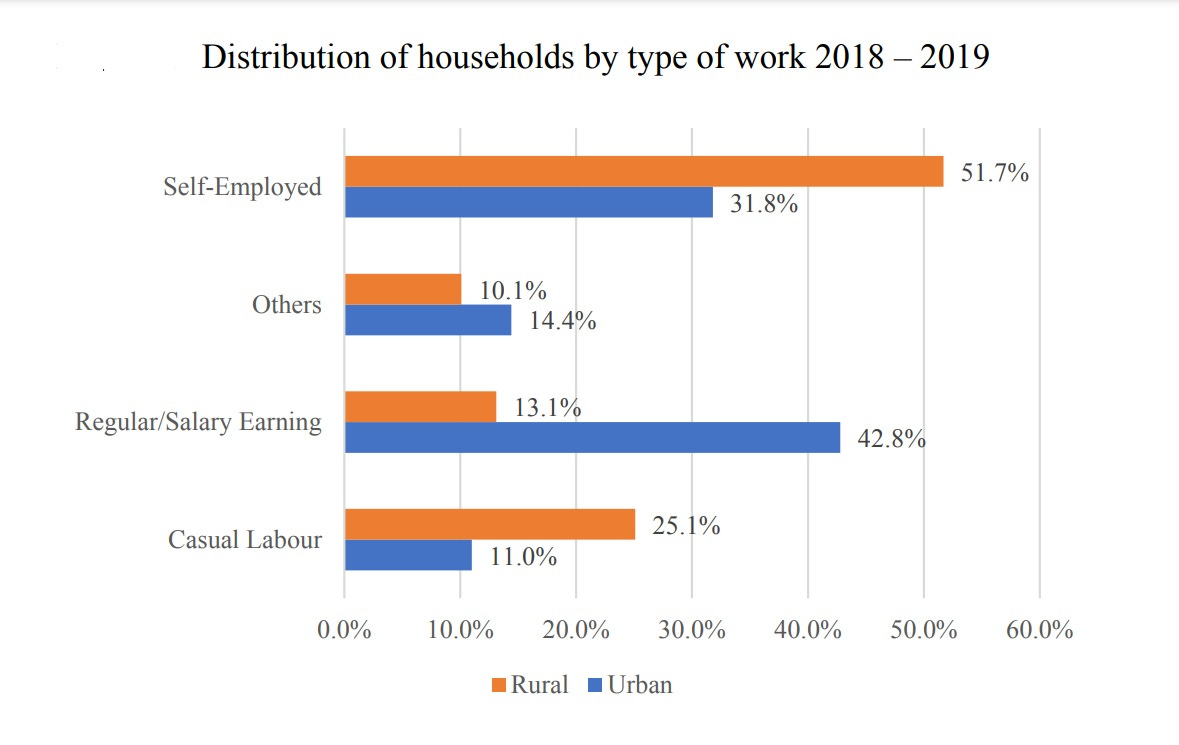

As shown in the chart below, the majority of Indian households are either self-employed or involved in casual labour. In urban areas, 42.8% of households have regular salaried earnings (formal) while in rural areas, only 13.1% have regular salaried earnings. In rural areas, nearly 76% of households are self-employed or casual labour.

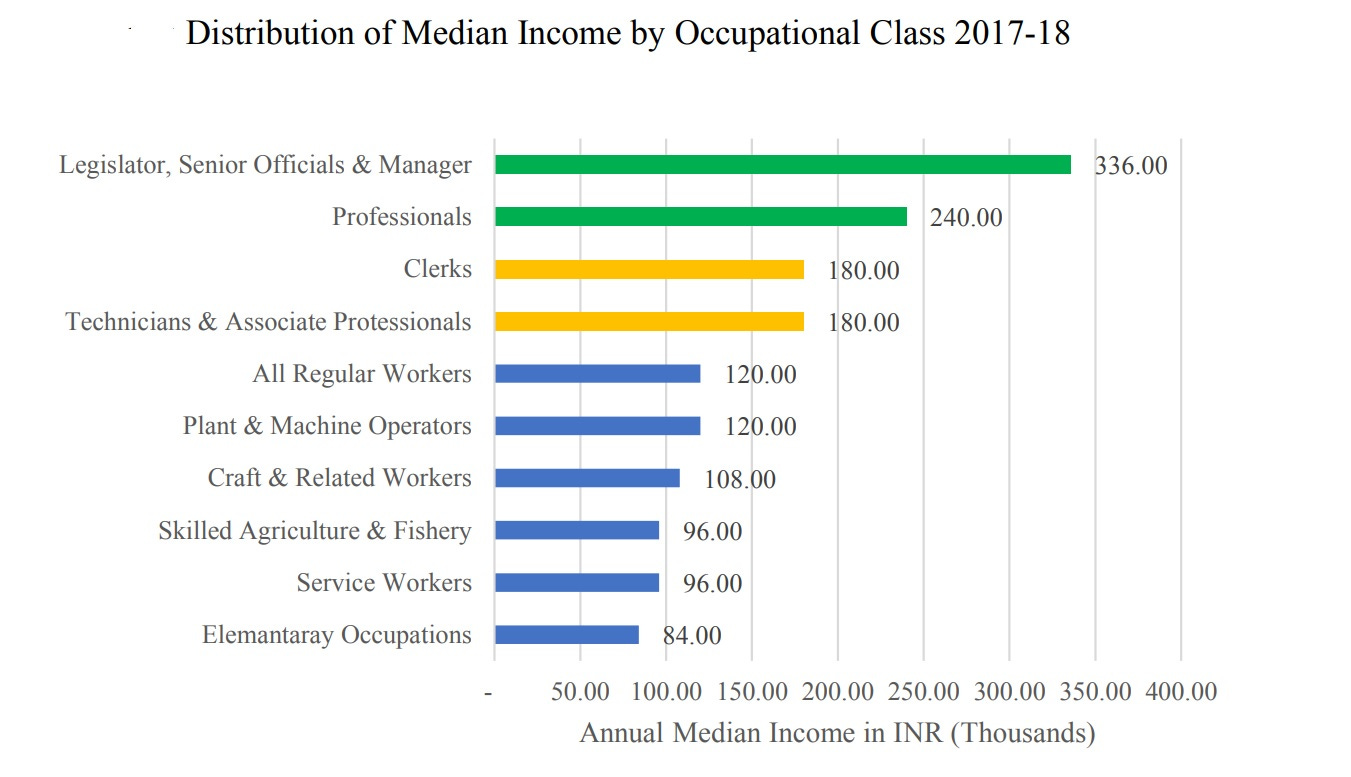

On the employment patterns and median income, Eggiman and Knedzia analyse and argue:

Regarding employment patterns and income, the lower middle class is predominantly in clerical or customer service occupations. Furthermore, they are also engaged in the technical areas where specialized knowledge is required. The upper-middle class is in the highest professional level of the natural sciences, such as engineering or medicine. The high earners occupy legislator, corporate manager or general manager positions in the private sector.

Economic liberalisation resulted in the rise of a new middle class. But due to the incomplete structural transformation project, only a tiny percentage of Indian households were able to make it to the genuine middle-class bracket. This genuine middle class benefited was poised to benefit as they were more educated, more skilled and were living in urban areas which benefited from economic liberalisation.

Watch this brilliant explainer of the Indian middle class by Aunindyo Chakravarty.