Dispatch #83: The politics of welfare in India

In this dispatch, we will reflect on the latest research on India's welfare politics, focusing on contemporary themes like the labharthi vs citizen debate, the revadi culture and freebies.

A recent article by Rajendran Narayanan points out the reframing of citizenship as a verb rather than a noun. This re-imagination of citizenship comes from the American writer and comedian Baratunde Thurston’s definition of citizenship as a verb which has 4 critical pillars:

To participate in ways that go beyond voting.

Deepen relationships with the community and show deep interconnectedness.

Understand power and use it for collective benefit.

Value the collective and work towards outcomes that benefit many and not just a few.

The article raises a larger question - should citizenship be reduced to a mere act of being a passive receiver of goods and services from the government? What will it take to transform the definition of citizenship from a noun to a verb, as described by Baratunde?

With elections just around the corner, I thought of dedicating this dispatch to the latest work on clientelism in India and the politics of welfare which has now become the main platform for both the ruling and the opposition parties.

Before diving deep into contemporary literature, let’s understand key terms and concepts on clientelism and welfare.

Concept #1

Programmatic and non-programmatic distribution: In ‘Brokers, voters and clientelism’, political scientist Susan C Stokes and others explain ways of political distribution of resources. They describe political distribution as the distribution of cash, employment, material benefits or other resources by the government to citizens. The problem is not distribution, instead how those resources are distributed becomes contentious. Stokes and others have further classified political distribution into programmatic and non-programmatic distribution.

A programmatic distribution is one where there is a well-defined public criteria for the distribution of goods and the goods are distributed to the citizens according to the criteria. In a non-programmatic distribution, either the public criteria for distribution are absent or the public criteria are subverted by the partisan criteria, the rules of citizens’ entitlement are undermined and the distribution is discretionary.

Within non-programmatic distribution, if there is an expectation by the political actors from the citizens to support them electorally in return for material benefits then that is referred to as clientelism. If there is no explicit expectation except goodwill then that’s partisan bias. Within partisan bias, if the benefits are given to the individuals to have their tacit support, then that’s the electoral diversion of public programmes and if the benefits are given to a geographical area in return for support then that is called the pork-barrel politics.

Stokes has defined clientelism as, ‘the proffering of material goods in return for electoral support, where the criterion of distribution that the patron uses is simply: did you (will you) support me?’.

Read more: The new social contract

Concept #2

India as a dizzying state: The focus of the current ruling dispensation is to meticulously identify and target beneficiaries for delivering private goods (toilets, gas connections, bank accounts) using direct transfers and leveraging architecture provided by the JAM trinity. To deliver these private goods the frontline bureaucracy of India has expanded its coverage and significantly improved efficiency. Milan Vaishnav asks whether the Indian state has been turned upside down from what Lant Pritchett once said about India, that it is a flailing state. Pritchett argued that the elite institutions (the head) were working well while the frontline institutions (the limbs) were facing challenges in delivering basic services and goods. Vaishnav argues that due to the new welfare push the limbs are entrusted to deliver efficiently.

He explains:

The welfare push of the Narendra Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government at the Centre, designed in Delhi but implemented by state and local authorities, has produced results that have pleasantly surprised even cynical observers. From toilets to gas connections, and electricity hook-ups to bank accounts, the frontlines of the Indian state have managed to significantly expand the extent of India’s welfare net. In sum, it is an apt time to revisit Pritchett’s assessment, not only because India’s head has demonstrated newfound weakness, but also because its limbs have shown surprising signs of effectiveness.

Read more: From ‘flailing state’ to ‘dizzying state’.

Concept #3

Politics of ‘vishwas’ or democratic accountability: PM Modi has already set the tone for his election campaign where he would remind the voters about the ‘Modi ki guarantee’ to deliver goods and services. This attribution of delivering goods (mostly private) to a leader is the key element of clientelistic politics. Neelanjan Sircar describes this as the ‘politics of vishwas’. This brand of politics is personality-driven, people always trust the charismatic leader to make the right decisions and power is centralized.

He adds:

In traditional models of democratic accountability, i.e. the politics of vikaas, there is little room for the role of the political mobilization and little discussion of what makes voters turn out to the polls. In the politics of vikaas, the voter looks at the choices available to her and selects the candidate or party most likely to deliver economically or closest to her in terms of ideology. These models require that voters can identify a stable set of issues consistent with their preferences and have sufficient information on the preferences and attitudes of political actors. In the politics of vishwas, the reverence to a particular politician is explicitly a function of how well the individual politician can connect to the voter (or, perhaps, demonize the opponent) – chiefly through media or the strength of party organization.

Read more: It’s the economy, stupid?

Concept #4

Brokers in clientelistic politics: Tariq Thachil and Adam Auerbach have defined brokers as individuals ‘who facilitate the exchange of electoral support for access to goods, services and protection in clientelistic settings’.

Similarly, Paul D Kenny in his book ‘Populism and patronage: Why populists win elections in India, Asia and beyond’ explains that in traditional patronage politics, the central leader is connected to the masses through intermediaries called brokers who distribute public goods in return of political support and rents in return for the services. The brokers consolidate political support and give it back to the central leader, up in the chain.

The new welfare architecture of India, however, removes the middlemen and enables the central leader to bypass the brokers and establish a direct connection with the voters. The delivery of private goods attains a very high level of efficiency and the successful delivery using technology is attributed to the central leader.

Read more: What explains the rise of a strongman in a democracy?

Concept #5

New Welfarism: Coined by Arvind Subramanian this welfare strategy ‘represents a very distinctive approach to redistribution and inclusion. It does not prioritise the supply of public goods such as basic health and primary education as governments have done around the world historically. Instead, it has entailed the subsidised public provision of essential goods and services, normally provided by the private sector, such as bank accounts, cooking gas, toilets, electricity, housing, water and cash’.

The government’s single-minded focus on delivering these private goods can be assessed by reading the Economic Survey of India 2021 in which an entire chapter was dedicated to the coverage of these goods. The survey calculated the Bare Necessities Index (BNI) by assessing the coverage of housing, water, sanitation, electricity, and clean cooking fuel. The survey claimed that between 2012 and 2018, bare necessities coverage increased dramatically in India.

While the bare necessities goods might have a positive impact, the focus on other pressing or complex ‘sticky’ issues and public goods provisioning has been diluted. Subramanian argues that while the coverage of necessities has improved significantly, child malnutrition in India has also increased. For him, this is a story of retrogression and not of progress. The ‘New Welfarism’, as he calls it, means using public funds to provide private goods to the citizens as basic needs, while withdrawing focus on distributing public goods widely. The New Welfarism approach not only consists of conviction but also of calculation. Conviction of providing goods and services to improve the recipients' living conditions; calculation of providing tangible private goods that can be measured and later be benefited for electoral purposes.

Now that we have familiarized ourselves with basic ideas on welfare and clientelistic politics in India, let’s survey some of the latest work on welfare in India.

Techno-patrimonialism:

Right after the three state elections in Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh, Yamini Aiyar, wrote an insightful article where she coined the term ‘techno-patrimonialism’- a welfare architecture which is not based on the poor exercising their rights, instead it reduces citizens as passive recipients of goods (labharthis) as largesse from the state with a clear intention of winning voter loyalty. Aiyar explains:

I posit that India is coalescing toward a “techno-patrimonial” character of welfarism, one that strips itself of any emancipatory goals such as advancing social citizenship and building solidarity. Instead, it casts citizens as passive recipients (labharthis) of state largesse rather than active claim-making, rights-bearing actors. This form of welfare is critical to politics of the contemporary moment, where political power is increasingly manufactured through the deification of the leader and unbridled voter loyalty extracted through welfare benefits.

The article explains reasons why techno-patrimonialism has emerged as the default version of welfare in India today.

India’s structural transformation has been unable to create opportunities for Indians. The State of Working India 2023 report highlights the disconnect between the economic growth in India and employment.

The political response to this crisis has been non-existent.

The failure to address this growing problem over the years has resulted in what Rathin Roy calls the ‘compensatory state’ logic of welfare which essentially means that the state, to compensate for those who have been left behind, will shift spending money from public goods to providing private goods. This compensation could be cash or in-kind transfers. This takes away financial resources being spent on developing human capital, thus increasing productivity and incomes.

Aiyar adds:

It strips the welfare discourse of any serious engagement with questions of redistribution and solidarity. However, in an electorally competitive democracy with a structurally skewed economy, the compensatory logic offers a tantalising alternative to politicians who need to respond to voter needs.

This welfare state has 2 key features:

Welfare is not seen as the state's responsibility to the rights-bearing citizens. Instead, it is seen as transferring assets to duty-bound citizens.

The duty-bound citizens, receiving private goods from the state are referred to as labharthi. This group, hence, becomes extremely vulnerable to political mobilization by the political parties. With a rights-based approach absent from the welfare, the citizens are just passive recipients who need to return the favour through electoral support.

Aiyar further argues:

This form of welfare mobilisation achieves two goals. One, by defining and mobilising voters around the category of “beneficiaries” it delinks the welfare discourse from rights mobilisation. In doing so, it effectively casts citizens as passive recipients of welfare beholden to the benevolence of the state rather than as active claimants of rights. Two, it creates the mobilisation space for political parties to forge a direct relationship with the individual voter. In this process, it undermines collective interest-based claim-making on state resources. There is today a critical but subtle shift in the repertoire of electoral mobilisation strategies adopted by political parties, away from an exclusive reliance on caste and religion-based mobilisation and towards a caste and religion-neutral social base of beneficiaries, the labharthi varg.

Read more: Citizen vs labharthi? Interrogating the welfare state

India’s transformative welfare architecture:

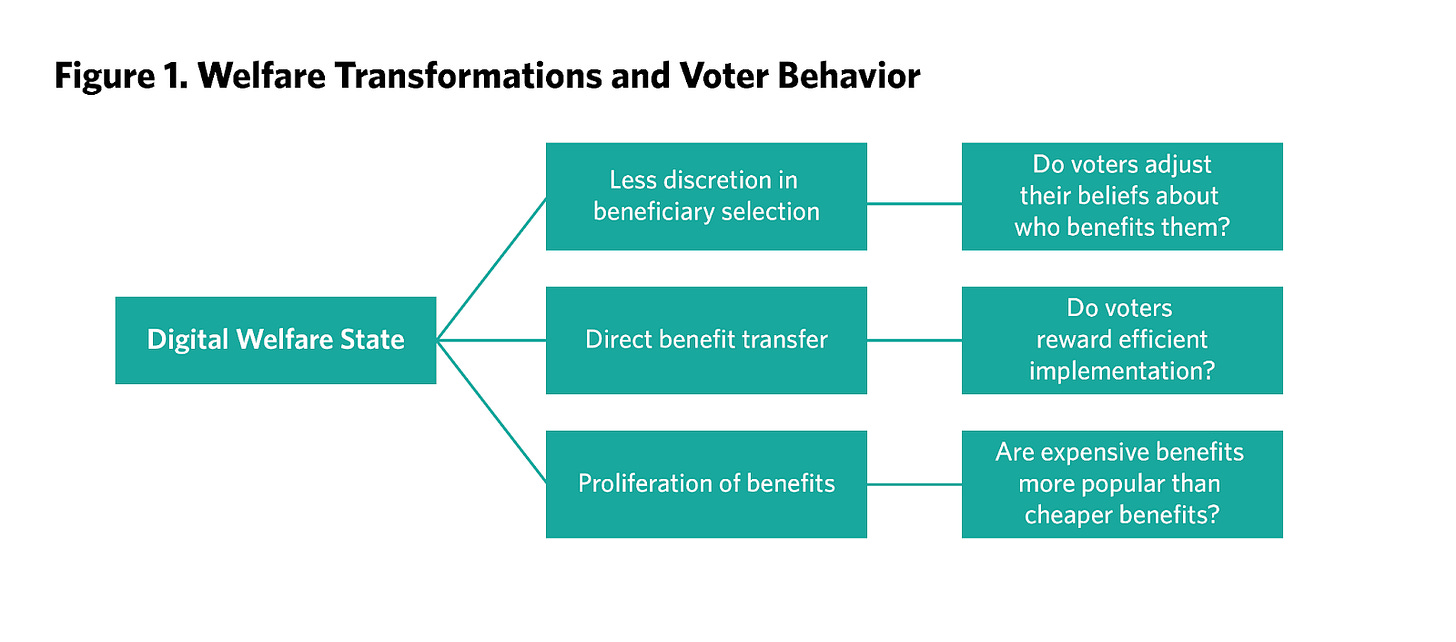

In an essay titled ‘When does welfare win votes in India’, researcher Shikhar Singh explains three transformative changes in the functioning of the Indian welfare state and their implications on voters’ behaviour:

Reduced discretion in the selection of beneficiaries: Removes middlemen as brokers and helps the central leader establish a direct connection with the voters. This also helps in establishing a direct and clear attribution of the delivery of goods to the leader.

Direct transfer of benefits: Leads to efficient welfare implementation.

The proliferation of benefits: Expensive benefits to a few people versus cheaper benefits to more people.

Rules-based transfer of goods, using technology has reduced ethnic or caste-religion-based voting in India, to some extent, argues Singh. It doesn’t matter for the core voters of a party to continue supporting it even if the welfare measures have reached out and benefited voters who were not the traditional supporters of that party.

On the question of whether voters reward parties based on just the benefits associated with the welfare programs (outcomes) or the efficient distribution of welfare (process), the study found that the voters value the former more than the latter. The process is rewarded ‘modestly’ than the outcomes (welfare programs and people benefiting from them).

Singh concludes:

The transformative changes in India’s welfare state are impacting voting behaviour in nuanced ways, with signs of both change and continuity. Rule-based selection of beneficiaries has produced cross-ethnic distribution at scale, disturbing the prevailing ethnic-clientelistic equilibrium. Despite this trend, the instrumentalist logic of identity voting persists at many levels of electoral competition. Even though direct benefit transfer has potentially improved last-mile delivery, voters appear to privilege outcome over process.

Reading list:

Technology and clientelist politics in India by Steven I. Wilkinson:

This paper argues that new computers, smartphones, and universal ID technologies are reducing the incentives for political clientelism in the delivery of social programmes in India, especially by allowing party leaders to bypass local brokers to credit-claim for better service delivery and allowing politicians to deliver programmatic service delivery much more efficiently than in the past, with fewer diversions. Politicians are responding to these changed incentives, not surprisingly, by investing more money in large social programmes, supporting technological efforts to improve their efficiency, and increasing campaign expenditures to advertise these improvements and link them to party leaders at the expense of local brokers who used to monopolize these local party– voter linkages.

It is widely believed that clientelism—the giving of material goods in return for electoral support—is associated with poorer development outcomes. However, systematic cross-country evidence on the deleterious effects of clientelism on development outcomes is lacking. In this paper, we examine the relationship between political clientelism, public goods provision, and governance quality using cross-country panel data for 161 countries for the period 1900–2017. We distinguish between two manifestations of political clientelism—whether vote-buying exists, and whether political parties offer material goods to their constituents in exchange for political support (non-programmatic party linkages). We find negative effects of political clientelism on development outcomes, with increases in clientelism leading to lower coverage of welfare programmes, increased political corruption, and weaker rule of law. We also find that the deleterious effects of political clientelism are mainly through non-programmatic party linkages rather than the practice of vote buying.

This paper shows that under clientelism, private benefits are effective in generating votes, but public goods are not. The empirical evidence for this is provided in two different ways. One examines changes in the allocation of local government program benefits across villages as a result of exogenous shocks to political competition. The other studies how the political support expressed by individual heads of household responded to variations in benefits they received, instrumented by variations in average program scale at the district level. The results corroborate each other in a manner predicted by a theoretical model of politically manipulated budgets. Identifying the patterns of resource allocation consistent with political clientelism is an important first step towards assessing its implications for development. Clientelism can potentially lead to three main distortions. First, since voters are less responsive to receiving benefits from infrastructure projects, there could be an under-provision of public goods as a consequence of clientelism. Second, since the inter-village allocation of benefits depends on political alignment across the tiers of government, clientelism is a source of inequality in resource allocation across regions. Third, it is possible that the discretion allowed to local politicians could result in resources being diverted or misused for corrupt purposes. However, on the other hand, clientelism could lead to better targeting of resources within local jurisdictions. Local political brokers have better information about potential beneficiaries, which can be exploited by elected officials for redistribution of private benefits or provision of insurance against shocks. If the distortions generated by clientelism are bigger than the gains from better targeting of resources, switching from discretionary allocation of program benefits to rule-based allocation may be desirable.

It has been argued that since 2014, under the BJP-led central government, welfare benefits in India have become better targeted and less prone to clientelistic control by state and local governments. Arguably this has helped to increase the vote share of the BJP vis-a-vis regional parties. We test these hypotheses using longitudinal data from 3500 rural households in the state of West Bengal. We fail to find evidence that the new “central” programs introduced after 2014 were better targeted than traditional “state” programs, or that the targeting of state programs improved after 2014. Households receiving the new “central” benefits introduced in 2014 were more likely to switch their political support to the BJP. However, changes in the scale, composition or targeting of these programs, in clientelistic effectiveness of traditional state programs or household incomes, fail to account for the large observed increase in the voters' support for the BJP. Non-Hindus, especially recent immigrant non-Hindus, were much less likely to switch support to the BJP, even after controlling for benefits received and changes in household incomes. Our results suggest that ideology and identity politics were more important factors explaining the rising popularity of the BJP.

Impact of Modi’s welfare policies by Diego Maiorano:

Welfare and development certainly helped to give substance to Modi’s narrative and political messaging, but on their own, they did not move many votes. It seems more plausible that many Indian voters have chosen the whole “Prime Minister Package”, of which welfare is just one of many, and, most probably, not the most important dimension. Perhaps the most important way in which welfare plays a political role is that it constitutes a constant and widespread source of visibility for the prime minister. Modi’s pictures are on display in ration shops and billboards presenting welfare schemes and on the very name of most of them. In this sense, Modi was able to build a very direct link between the welfare beneficiaries and himself, contributing to the construction of his persona as a leader who takes care of ordinary Indians.

Narendra Modi’s welfare ‘freebies’ offer an election boost by John Reed and Andy Linn

Very interesting read on the transformation of Indian State.