Dispatch #70: 9 charts that show how health and voters’ preferences are connected in India

In this dispatch, we will explore the findings from a very important latest study on public health and democracy in India

I have spent a considerable amount of energy and this newsletter’s space to discuss the relationship between public services delivery especially public health, democracy and voters’ preferences in India. I also tried to put all of this under a larger framework of democratic accountability.

I will quickly summarise broad arguments from my previous dispatches that will help set the context for delving into the latest study titled ‘Democracy and Health in India’, conducted by CSDS, King’s India Institute (King’s College London) and CSEP.

What ails India’s healthcare- Part 1: We looked at the data on India’s poor health infrastructure, health indicators and expenditure and asked why Indian voters don’t punish political parties on issues such as poor public health services. With Covid-19 in the backdrop, we explored why there isn’t a demand for better health services among Indian voters.

What ails India’s healthcare- Part 2: We delved into the reasons for the poor demand for public health services by Indian voters. Using Monica Dasgupta’s hypothesis we looked into the specific characteristics of public health that diminish its criticality.

The politics of healthcare in India: We explored a framework for the political priority of health in India. We also looked at public service delivery from a new lens of ‘new welfarism’, a term coined by Arvind Subramanian.

The unique connection between democracy, governance and healthcare: We did a deep dive into the literature on the quality of democracy and healthcare. Briefly, we also discussed key instruments that can be used to improve governance and health service delivery in India.

Financing healthcare in India: We looked into the public finance aspect of healthcare in India and also discussed the health financing transition due to economic growth in the country.

It’s the economy stupid: This was one of the initial dispatches where I introduced the concept of democratic accountability and explained how the rise of charismatic leaders undermines that accountability and stunts the demand for better governance and service delivery.

The buck stops here: In this dispatch, we looked further into the idea of democratic accountability with a special focus on voter backlash during a crisis. This was written in the middle of the deadly second wave of Covid 19 in India in 2021.

The new social contract: Using the idea of ‘claiming the state’ by Gabi Kruks Wisner we explored concepts such as distributive politics and clientelism and how does poor in India make claims to the state.

‘Prashn nahi uthta’- Unpacking democratic accountability: Here we looked at the three critical pillars of democratic accountability- answerability, responsiveness and enforceability.

Is health an electoral priority in India?

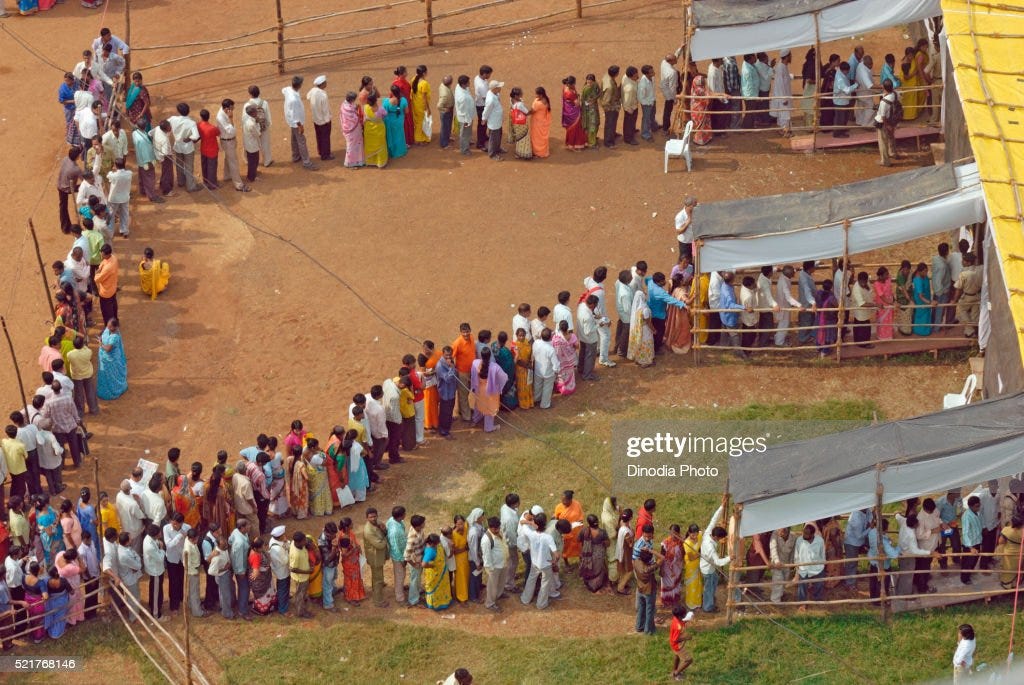

The answer to this question is what the CSDS study has tried to find out. The study is a result of the survey which was undertaken in 5 states to understand Indian voters’ perception of health systems and services as an electoral issue.

Broadly, the study finds that:

The perception that health is completely out of the picture when an Indian voter goes out to vote, is not accurate. While health is not the top priority of voters, there is a latent demand for ‘greater government prioritisation of healthcare'.

The majority of voters agreed that it’s the government’s priority to provide health care services.

People who think that health services have improved tend to vote for the political party in power more than those who do not see any improvement.

There is a high degree of confusion as to which level of government is responsible for health service delivery. Because of this flaw in attribution, accountability gets undermined.

Now let’s look at the data more closely.

In conventional election surveys, voters might seem to have de-prioritised healthcare as an election issue. In the 2019 National Election Survey (NES) findings, CSDS found that 0.3% of their respondents thought that the condition of hospitals and health facilities is an important electoral issue. At the same time, 13.2% of voters thought that development and 10.5% of voters thought that lack of jobs and unemployment were the most important election issues. However, it is not clear what aspect of development the voters have thought to be important. In the CSDS study, when asked about the specific aspect of development, health is the number three priority after jobs and schools.

When asked about what is their biggest concern over the next five years, 20% of respondents said that it’s either their own health or the health of a family member that bothers them the most.

The provision of health services plays a significant role in voters’ decision-making. 61% of respondents (22%: To a great extent and 39%: To some extent) said that health provisioning impacted their voting decisions in the assembly elections. Similarly, 56% of respondents (27%: To a great extent and 29%: To some extent) said that health facilities impacted their voting decisions in local elections. And, 57% of respondents (25%: To a great extent and 32%: To some extent) said that it impacted their voting decisions in the national elections.

The majority of respondents said that government is responsible for providing healthcare facilities. Across all three categories- people who visited government hospitals, people who visited private hospitals and people who never visited any hospital- voters were of the view that the government is responsible for healthcare facilities. This is interesting given the fact that a large proportion of healthcare needs in India are catered to by the private sector.

The authors of the study very aptly argue:

Voters expect the government to take responsibility for healthcare in India, but this is not necessarily something that they prioritise in elections, where other issues such as employment and inflation tend to be the most dominant. When we consider voters’ considerations across various state assembly elections, even after the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, very few people mentioned health as the most important issue. However, when we dig beneath the surface and ask voters to consider what factors define development in their area, we find that health is viewed as one of the most important issues for improving the level of development – on par with education, and behind only employment. In other words, voters care about health more than may first appear. Furthermore, when asked, a majority say that the provision of health services affects their voting behaviour to some extent, particularly in state elections.

Assessing voters’ satisfaction with public services is a tricky proposition. High levels of satisfaction even though the quality of services not being good could be due to low expectations. Satisfaction may arise not only from the quality of services per se but also from how the quality ‘compares with users’ prior expectations’. There is ample research which suggests that overall satisfaction levels can be high even when the quality of services is not great. Kerry Ratigan has found that the questionable quality of healthcare services in China has not made any significant dent in the legitimacy of the government. Devadasan and others have argued that patient satisfaction between insured and uninsured patients doesn’t differ much.

The survey has found that there is a reasonably high level of satisfaction level with the overall healthcare services in India. While 79% of respondents (Fully satisfied: 37% & Somewhat satisfied: 42%) are satisfied with the overall healthcare system in India; 83% of respondents (Fully satisfied: 48% & Somewhat satisfied: 35%) were satisfied with treatment in the hospital last visited.

If you do a further deep dive into this piece of data you will find that not everyone is satisfied with the overall healthcare services. Those who are in good health are more satisfied than those who are in bad health. While 57% of those who are in very good health are fully satisfied with health services in India, only 24% of those who are in very bad health are fully satisfied.

The legislative and administrative positioning of healthcare between state and Union government adds another layer of complexity. According to the Seventh Schedule of the Indian Constitution, ‘public health and sanitation; hospitals and dispensaries’ comes within the State list. However, the Union government can design health policy and be involved heavily in its financing. Because of this ambiguity of positioning of healthcare, the ‘voters do not share a clear consensus on which level of government is most responsible for the functioning of government hospitals ’. The study shows that 37% of respondents identified state governments to be responsible for the functioning of government hospitals, while 14% and 17% of respondents thought that the central and local governments respectively are responsible. The authors of the study hence argue that ‘there has been a less pronounced pattern of centralisation of credit attribution for health than other areas of welfare policies’.

When it comes to attribution, the respondents were reasonably accurate in pointing out which levels of government are broadly responsible for that health scheme. 59% of respondents credit the central government for the flagship national health insurance policy- Ayushman Bharat. 45% credit the state governments for state health insurance schemes. For centrally sponsored schemes like Janani Suraksha Yojna and Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakaram, which are constitutionally state governments’ responsibility, more respondents feel that state governments are responsible. Having said that, a big proportion of respondents in the above categories have wrongly attributed the credit to the levels of government.

Further, the study claims that direct beneficiaries of health schemes are more likely to attribute credit to the correct tier of the government. Nearly 78% of beneficiaries of Ayushman Bharat were able to attribute the responsibility to the central government. The problem of credit attribution arises when the beneficiaries are covered by the state and central health insurance schemes.

The study further adds:

The survey suggests that voters lack a clear picture of which level of government is responsible for the delivery of services and programmes. Some programmes bear the clear imprint of the Prime Minister – such as PM-JAY or Ayushman Bharat – and are attributed to the central government by a significant proportion of voters. But with co-branding of PM-JAY with state-level insurance schemes, there is also considerable confusion among voters about which level of government is responsible. Voters are even less clear about how to attribute responsibility for other areas of health system functioning. This is understandable given the complex constitutional arrangements governing health, and the complex patterns of funding and operational responsibility. Such a picture of unclear credit attribution for health system functioning, in contrast to the often clearer attribution of welfare schemes, is also found in other federal systems in the global South. The picture of unclear attribution can be positive, in that there are stronger incentives for inter-governmental collaboration in strengthening health services where one level of government is not able – or does not seek – to monopolise electoral credit. Instead, credit can be shared between multiple levels of government.

Surprisingly, across the state, a sizeable proportion of the respondents feel that their local government is responsible for government hospitals even though local governments don’t have any constitutional authority in health. 31% of respondents in Gujarat and 31% in TN think that the local government is responsible for the functioning of hospitals.

Since the attribution to provide hospitals mainly lie with the state governments, it is safe to assume that Indian voters would engage more in performance-based voting on health issues during the state elections than the Lok Sabha elections. However, since voters ‘lack a clear consensus on who is responsible’, as seen in the above piece of data, it may dampen performance voting. Amongst the respondents who attribute the functioning of hospitals to the state governments are more likely to vote for the incumbent government if they think that the hospitals have got better than those who think that hospitals have worsened. This clearly shows that when healthcare services, which are visible, are doing well, the incumbent government at the state gets the benefit. This trend is ambiguous in the Lok Sabha elections. ‘Voters do not tend to reward or punish the central government in the same way, perhaps because they do not hold the central government responsible for the provision of health services’, claims the study. However, when the chief minister of the surveyed state is from the same political party as the one at the Union level (BJP in this case), voters have voted for the party during the Lok Sabha elections.

Hence, we can see that due to the complex constitutional distribution of legislative and administrative responsibilities for health between central and state governments, voters have to deal with a very high level of uncertainty when it comes to attribution. The study concludes by saying that:

The ambiguity over credit attribution may not be such a bad thing for cooperation between levels of government, even where they are governed by different parties, unlike in policy areas where credit is more clearly assigned to one level of government or the other. But the ambiguity also risks weakening lines of accountability. Our research suggests that less satisfied voters are more likely to blame their local government than their state government for poor performance, even though the local government has no constitutional responsibility in this field.